The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

Siwen LU

University of Liverpool

Abstract As a perennially controversial topic, swearing has been much discussed in the area of audiovisual translation. However, less attention has been paid to the multimodal analysis of swearing since previous research only focuses on the linguistic transfer or monomodal analysis of swearing. The main aim of this study is to investigate the subtitling of swearing by drawing upon the Systemic Functional Linguistics-informed multimodality. The main focus is to examine the multimodal construal of swearing at the three metafunctional levels, to investigate the semiotic interplay between verbal and non-verbal elements, and to consider whether this has different effects on the subtitled film. Criminal (2016), an American action film, is chosen for this study due to the prominence of swearing and physical violence in the film. The results show that the Chinese translation follows a target-oriented strategy and there is a strong toning-down tendency in terms of the subtitling of swearing. However, this does not mean that the original effects of swearing (e.g. expressing emotions, characterisation and signalling the aggressive nature of the atmosphere) are completely lost in the subtitled version. The loss of swearing in the subtitled film can be mitigated by many contextual factors in the film such as non-verbal elements, co-text, register established on the character’s first appearance, and genre. Therefore, this study highlights the importance of considering subtitles as only one element in the whole multimodal ensemble and treating the whole film as an entire system.

Keywords: swearing, multimodal, subtitling, metafunction

1. Introduction

This study investigates the subtitling of swearing from English into Chinese in the filmCriminal(2016) by drawing upon the Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)-informed multimodal framework. Officially imported into China in 2016,Criminal(2016), an American action crime film, was directed by Ariel Vromen and produced by Campbell-Grobman Films and Millennium Films. The film mainly depicts a death-row convict, Jerico, who is implanted with a dead CIA agent’s memories and skills to complete the agent’s unfinished mission. The film is chosen for this study for several reasons. First, it is a typical action crime film that makes prolific use of swearing, providing a good resource to investigate the subtitling of this feature. It is also representative of the broader corpus of action films imported into China. Furthermore, the pervasiveness of physical aggression, violence, and arguments in the film serves as an additional factor in the selection of this film since it provides a condition for a multimodal analysis of swearing and the investigation of its effects on the subtitled film. This study highlights the crucial importance of various multimodal contextual factors on the subtitled film and concludes by arguing that the toning down of swearing may not have a homogenising effect on the target text as there are micro (e.g. semiotic resources) and macro factors (e.g. co-text, genre and register) in the subtitled film to cue the functions of swearing.

Swearing represents an interesting topic for both linguistic and intercultural analyses as well as a translation challenge due to its offensive nature. It is a topic that has been much discussed in the area of audiovisual translation (Baines, 2015; Chen, 2004; Dobao, 2006; Han & Wang, 2014; Hjort, 2009; Pardo, 2015). However, less attention has been paid to a multimodal analysis of swearing since the abovementioned studies focus mostly on the linguistic transfer or monomodal analysis of swearing. It is crucial to adopt a multimodal approach to analyse the subtitling of swearing because swearing is a type of communication that is always accompanied by many non-verbal elements, such as facial expression, voice quality and body language, which are something that can indicate the actual intent of the use of swearwords and affect how a swearword is perceived (Jay, 1999; Ljung, 2011). These non-verbal elements are mainly used for expressing the interpersonal meaning of swearing, which are reinforced by other semiotic resources in film (e.g. mise-en-scène, cinematography, and sound).

In the Chinese context, swearing is a subject of particular interest: on the one hand, the semantic categories and linguistic structures of swearing differ in English and Chinese, which poses challenges to translators when dealing with certain swearwords; and on the other hand, the strict censorship and a lack of a film age-rating system result in the current situation that all audiovisual materials publicly shown in China must be appropriate for audiences of all ages. As a result, translators are encouraged to tone down swearwords in subtitles to meet the requirements of institutionalised censorship at the expense of the original vulgar flavour.

The act of swearing is versatile since it can fulfil a range of pragmatic, interpersonal and social functions, distinguishing itself from other communicative acts (Daly, Holmes, Newton, & Stubbe, 2004; Jay, 1992, 1999; Stapleton, 2010). In films, swearing plays a crucial role in the construction of characters and narratives. Expressing emotions is the most common function of swearing as it can carry powerful emotions both positively (e.g. happiness and joy) and negatively (e.g. anger and frustration) (Dynel, 2012; Ljung, 2011; Vingerhoets, Bylsma, & de Vlam, 2013). The powerful and dominant position of the speaker can also be reflected through the expression of negative feelings in certain interpersonal contexts (Stapleton, 2010). Additionally, the use of swearing also has some social functions such as increasing group solidarity or marking group identity (Montagu, 1967). This function of identity construction is extremely important for characterisation in films. Film directors or screenwriters usually include swearwords in dialogue to construct the identity or personality of certain characters, such as antiheroes (e.g. gangsters, drug-dealers, criminals or murders), especially in the genre of action thrillers or action crimes (Pardo, 2015). For some situations, swearing may play a crucial role in the thematic or narrative constructions while for other situations, swearing may just play a small role in expressing certain emotions of the character. The functions of swearing are highly dependent on the context as one swearword may serve different functions in different contexts or even one swearword may simultaneously perform more than one function in a single context (Stapleton, 2010). Therefore, the analysis of the functions of swearing in films needs to take into account context rather than analysing decontextualised dialogue, using a multimodal approach.

Following the introduction, the second section sets up the SFL-informed multimodal theoretical framework and the method of multimodal transcription adopted in this study. Subsequently, the third section presents the analytical procedures of this study. The fourth and fifth sections are the main parts of this study which present a detailed and systemic examination of the effects of micro (e.g. semiotic resources) and macro factors (e.g. co-text, genre and register) on the subtitled version ofCriminal(2016).

2. Theoretical foundation and methodology for this study

With the advent of the multimedia era and the development of digital technology, research in Translation Studies is no longer purely linguistics-based. Gottlieb (2007) indicates that there was a turn from semantics to semiotics in terms of the interest of Translation Studies and of special interest is the semiotic composition of the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) and the effects of semiotic interplay on the translation process and the end products. Audiovisual translation (AVT), especially subtitling, has benefited the most from this multimodal turn in Translation Studies due to the polysemiotic nature of audiovisual materials and the characteristics of subtitling (Pérez-González, 2014). However, there exists a gap between AVT research and the theoretical framework in Translation Studies as Gambier (2006, p. 7) suggests:

There is a strong paradox: we are ready to acknowledge the interrelations between the verbal and the visual, between language and non-verbal, but the dominant research perspective remains largely linguistic. The multisemiotic blends of many different signs are not ignored but they are usually neglected or not integrated into a framework. Is it not a contradiction to set up a data base or a corpus of film dialogues and their subtitles, with no pictures, and still pretend to study screen translation?

Compared to a monomodal approach which does not take into consideration modes other than language, a multimodal approach provides researchers with a holistic and comprehensive perspective on analysing the mechanism and process of meaning-making in multimodal environments. A multimodal approach is essential to AVT studies due to the complex and multisemiotic nature of the audiovisual text, which is therefore the most appropriate framework for the analysis of swearing.

In its construction of a multimodal theoretical framework for its analysis, this study draws upon the SFL-based multimodality framework (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996, 2006; van Leeuwen, 1996) and Bordwell and Thompson’s (2010) theoretical analysis of film as the theoretical foundations. The aim of the SFL-based multimodal analysis is to investigate how different semiotic resources achieve the three metafunctions (i.e. the representational, interactive and compositional) in multimodal texts and to examine the meanings that arise when different semiotic resources interact and integrate in multimodal texts over space and time (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996, 2006; van Leeuwen, 1996). Based on a metafunctional system, the SFL-based multimodal analysis involves developing systemic descriptions of semiotic resources according to representational, interactive, and compositional meanings and investigating the intersemiotic mechanism when different semiotic resources integrate in multimodal texts (ibid.). Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996) work of visual grammar is perhaps the most influential and significant contribution in the area of visual analysis since they extend the theoretical framework of SFL to analyse visual images and rename the three metafunctions (i.e. the ideational, interpersonal, and textual) in SFL as the representational, interactive, and compositional functions. Their work of visual design opened the door for multimodality and can be regarded as the foundation for extending and adapting social semiotics to other modes (Jewitt, 2009). However, their work focuses only on static images. As films are dynamically, spatially, and temporally unfolding texts, van Leeuwen’s (1996) visual grammar of films and Bordwell and Thompson’s (2010) theoretical analysis of film are also be adopted in this study to account for the dynamicity of filmic texts.

For the purpose of this study, the three metafunctional levels for the multimodal analysis are the representational, interactive, and compositional. Representationally, in visual images, modes can function to depict the identification (who the social actors are), activity (what is taking place), circumstances (where the action is taking place), and attributes (what the participants’ characteristics are) by adopting Royce’s (2002, p. 193-194) terms. Interactively, Kress and van Leeuwen (2006, p. 48) point out that in every communication there are two types of participants: “the represented participants within the text and the interactive participants actually engaged with the act of communication”. The interactive relation between these social actors are mainly accomplished through three semiotic resources: gaze (e.g. direct or indirect), social distance (e.g. cameral shot), and point of view (e.g. camera angle) (ibid.). In filmic texts, the interactive relations between these social actors are not static, but dynamic and flexible through the movement of the camera and the subject. Additionally, different colours, light and shade can be employed to construct the motion of modality in moving images. Furthermore, in films, sound track (e.g. volume, intonation, pitch and rhythm), and the acting and performance of actors (e.g. kinesics, proxemics, body language and facial expression) also play an important role in boosting the interpersonal meaning accompanied by the speech (Bordwell & Thompson, 2010). Since swearing is typically regarded as interpersonal, these elements for constructing the interactive metafunction are of crucial importance to account for the interpersonal functions of swearing as they are not only conveyed through the verbal channel, but also non-verbal channels, including mise-en-scène, cinematography, and sound in films. Such non-verbal elements are of high relevance in subtitled films due to the fact that they can provide different ways of compensation or mitigation when the original swearing is toned down in the subtitles. Finally, representational and interactive meanings are organised together to achieve compositional meanings, mainly through the three aspects of information value, salience and framing (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996, 2006). Specific compositional construction can draw viewers’ attention to or foreground specific characters and their corresponding verbal and non-verbal communication when they swear.

The adoption of the SFL-informed multimodality to analyse the subtitling of swearing offers a number of benefits. Through the multimodal analysis, the linguistic communication is amplified and highlighted simultaneously by other filmic elements which affect the interpretation of any given utterance and in particular where swearing is concerned. Additionally, a framework from an SFL perspective is beneficial to the contrastive analysis between the ST and the TT in film subtitling since it is an approach that can be used to analyse both the spoken and written texts, to compare the similarities and differences between the ST and TT systemically, and to identify the translation strategies used when translating swearwords. Furthermore, the metafunctional analysis provides researchers with a unifying platform to compare different semiotic resources in order to investigate the functionalities and organisations of different semiotic resources and how they interact and integrate to make meaning (Jewitt, Bezemer, & O’Halloran, 2016). Specific to swearing, it provides researchers a conceptual tool to examine the multimodal construal of swearing from the three distinct metafunctional perspectives so that researchers can have a holistic understanding of how these contextual factors affect the transfer of swearing in the subtitled films. Since subtitles are only one part of the multimodal ensemble, it is necessary to treat the whole film as an entire system and present swearing and its translation in relative heteronomy from their context in the multimodal text.

In order to approach such analysis, this study uses an adapted version of Taylor’s (2003) multimodal transcription. The theoretical basis of Taylor’s (ibid.) multimodal transcription lies in the multimodal discourse analysis which allows researchers to analyse data both intermodally and intramodally. Since the transcription involves deconstructing filmic texts into individual constituent parts, it can facilitate a systemic understanding of the interaction between verbal and non-verbal elements. From a translational point of view, the multimodal transcription is beneficial for the analysis of subtitling because it shows how meaning is conveyed through various semiotic resources systemically and how subtitles interact with other semiotic resources to make meaning. This thereby can show how dispensable or indispensable the verbal element is in different situations and the effects of the non-verbal elements on the subtitled film (ibid.).

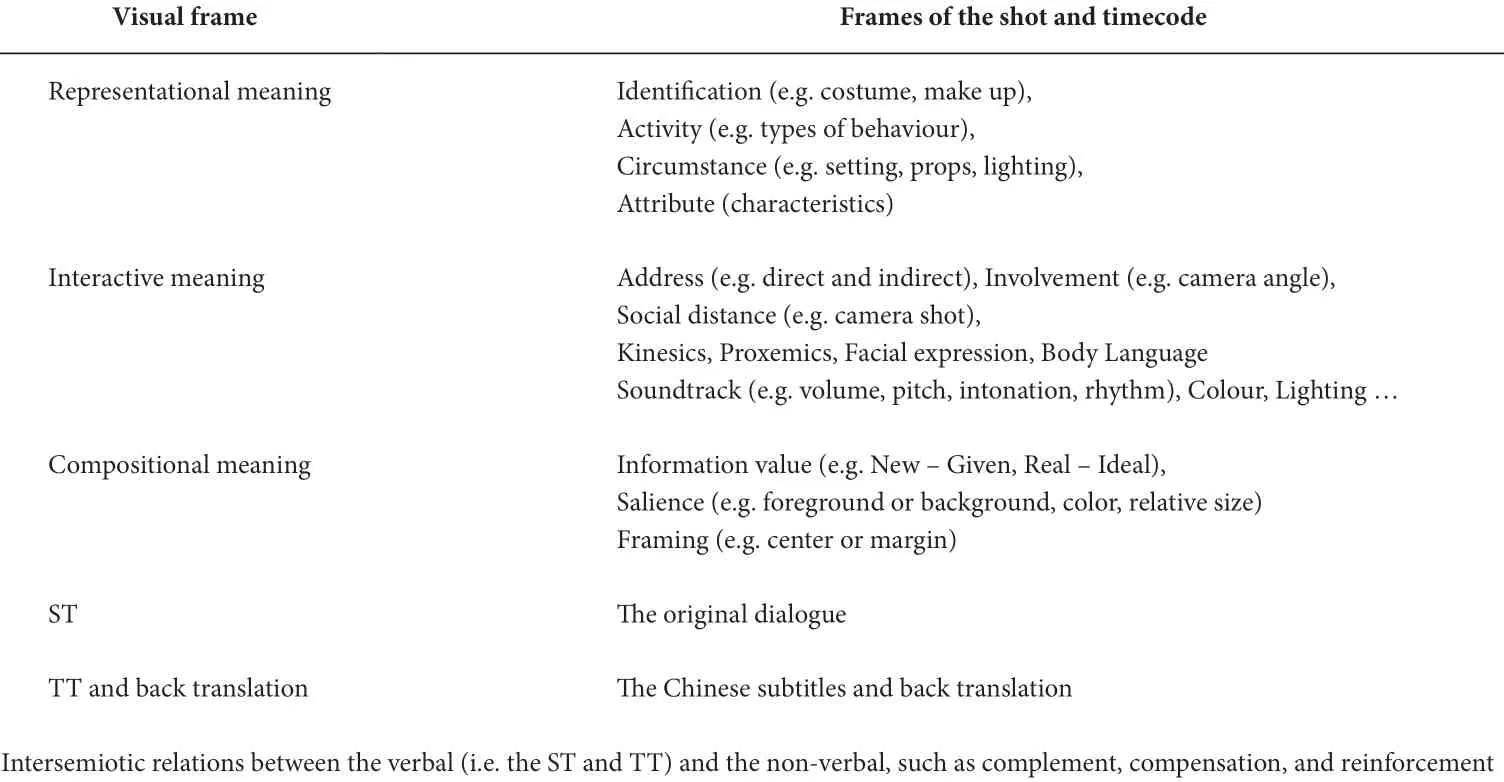

Table 1. The multimodal transcription used in this study

Drawing upon Taylor’s (2003) work, a multimodal transcription is designed for analysing the instances of swearing in this study, as shown in Table 1. The adapted multimodal transcription used in this study comprises seven rows in total. The first row contains the frames of the shot in which swearing appears with the corresponding timecode. The next three rows are divided according to the three metafunctions and contain the key, relevant semiotic resources that achieve the three metafunctional meanings respectively. As the main function of swearing is interpersonal, more attention is paid to the interactive construction in the transcription. The next two rows include the original dialogue and the subtitles. Although the original dialogue and the subtitles can also serve the three metafunctions, from a translational point of view and for the purpose of focusing on the analysis of subtitling, they are positioned in separated rows to make them salient. It is worth noting that in film they work in tandem with other semiotic resources to construct the overall meanings. Lastly, an additional row is added to investigate the semiotic interplay between verbal (i.e. the ST and TT) and non-verbal elements when constructing the functions of swearing in the original and the subtitled film respectively.

3. The analytical procedure

The analysis in this study is contrastive and systemic, and presented as follows: first comes a general overview of the use of swearing, and the distribution of the semantic categories and the functions of swearing in both the ST and the TT; then in order to account for a detailed and systemic examination of the effects of semiotic resources on the subtitled film, an SFL-based multimodal analysis is conducted to investigate the subtitling of swearing from a metafunctional perspective, adopting the multimodal transcription. Particular attention is paid to the situations in which swearwords are deleted or desweared in subtitles since these are the most frequently used translation techniques for subtitling swearing, both inCriminal(2016) and in the wider corpus of films imported into China. These are also the instances where other non-verbal resources offer the potential to mitigate the effects of omission and de-swearing.

4. Data analysis

4.1 General overview: A quantitative aspect

In total, there are 60 instances of swearing inCriminal(2016). They are analysed below according to Ljung’s (2011) typology of swearing, based on the themes and linguistic functions of swearing. The themes of swearing refer to the different taboo areas constructing swearing. Ljung (ibid.) suggests five major themes (i.e. the religious, scatological, sex organ, sexual activities, and the mother/women themes) and several minor themes (i.e. ancestors, animals, death, disease, and prostitution themes) of swearing. From a perspective of typology, by comparing the ST and the TT, there exists a significant mismatch in the choice of semantic categories of swearing. Based on Ljung’s (ibid.) classification, six categories of swearing are found in the ST while in the TT only four categories are found.

Table 2 shows that fewer categories of swearing in Chinese are used to translate their English originals. The theme of sexual activities is the most frequently used category of swearing in the ST, which confirms Ljung’s (2011) argument that sexual activities is the most frequently used category of English swearing because the word ‘fuck’ is the most colourful, versatile and multifunctional swearword in the English language. It is worth mentioning that sometimes one swearword may contain more than one theme simultaneously. According to Ljung (ibid.), it is the dominant theme that is more essential to understanding the expression. Taking the swearword ‘motherfucker’ as an example, although the word contains both the themes of sexual activity and mother, it is the mother theme that dominates. However, compared to the ST, chaos is the most frequently used category in the TT. This disparity reflects the fact that there is a gap between the two lingual-cultural systems and the use of swearing needs to conform with the norms of the target-language culture. Additionally, the table shows that the overall number of instances of swearing in the ST is decreased by nearly two thirds in the TT. This result reflects that most of the swearing in the original is toned down in the Chinese subtitles. The detailed analyses of the reasons and effects of this tendency to tone-down swearing in the subtitled film are analysed in the following sections.

Table 2. Distribution of swearing by semantic categories

4.2 A functional analysis of swearing in the ST and TT

In order to investigate how swearing is used in the ST and TT and to examine whether there are shifts or loss of functions in the Chinese subtitles, this section illustrates the distribution of swearing across functions in the ST and TT, and some comparisons between the ST and TT in terms of the distribution of the functions of swearing are also made.

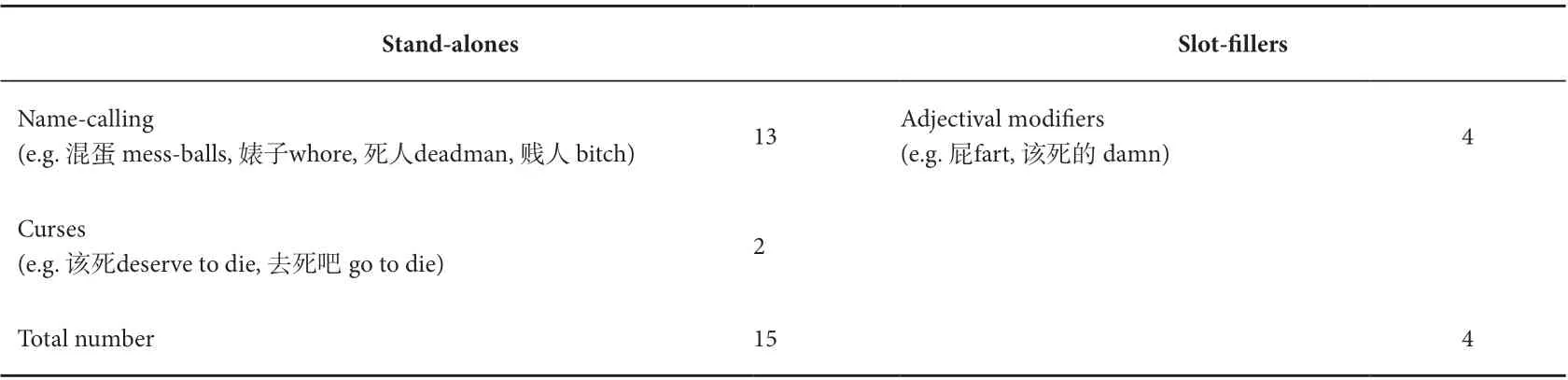

Besides the themes of swearing as illustrated in the previous section, Ljung (2011) also divides swearing into two major subgroups based on the linguistic functions of swearing: stand-alones and slot-fillers, depending on whether the expression can be an utterance on its own. Stand-alones are the sentences that can function on their own and include the usage of swearing such as expletive interjections, curses, and name-calling. Slot fillers are not independent utterances and include adjectival modifiers, adverbial modifiers and emphasis. They can indicate a high degree of emphasis on the following words while they can also be used for non-intensifying functions such as expressing the speaker’s dislike of the following referents, normally a person or an object.

In the study onCriminal(2016), the two major groups of swearing -- stand-alones and slot-fillers -- are used as well as a third category, idiomatic swearing, which is used to classify instances of swearing such as ‘fuck off’ and ‘fuck up’ which fit neither into the category of stand-alones nor slot-fillers as classified by Ljung (2011). The instances of idiomatic swearing are found in the ST only. The distribution of the functions of swearing in both the ST and the TT is shown below in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3. Distribution of swearing across functions in the ST

Table 4. Distribution of swearing across functions in the TT

In general, Table 3 shows that in the ST, most instances of swearing are stand-alones, followed by slotfillers and idiomatic swearing. Specifically, the high proportion of naming-calling can be explained by the genre and the content of the film since they are used for signalling a violent and aggressive atmosphere as well as portraying Jerico’s identity as an antisocial criminal, as he frequently uses name-calling such as ‘shit’, ‘motherfucker’, and ‘a(chǎn)sshole’ to express his dislike of other people. From table 4, it can be found that in accordance with the ST, most swearing takes the form of name-calling in the TT. However, there exists a slight discrepancy in terms of the functions of expletive interjections and curses as in the TT expletive interjection is the least frequently used function. This result could be explained by the fact that 該死 (deserve to die) and 去死吧 (go to die) are the two most common curses in Chinese, which can also serve the functions of expletive interjections in English swearing, such as being used as reactions to the sudden shock or used as catharsis to express the speaker’s emotions. Additionally, in terms of slot-fillers and idiomatic swearing, there is a mismatch in the number of the functions due to the differences between the two lingual-cultural systems and the tendency to tone-down in the TT.

4.3 The translation of swearing in the TT

Before examining to what extent the original functions of swearing are retained in the TT and the effects of semiotic interplay on the subtitled film, a general overview of how each function is relayed in the TT is provided in order to account for how English swearing is actually transferred into Chinese. In total, five translation techniques are identified. The distribution of each function and its corresponding translation technique is shown in Table 5 below:

Table 5. Functions of swearing and their translation techniques

Table 5 shows that de-swearing is the most common translation technique inCriminal(2016), while literal translation is the least common translation technique. It is apparent that there is a strong toningdown tendency in the subtitling of swearing since 67% of the swearing in the ST is either omitted or desweared in subtitles, which is consistent with the fact that in China films must be appropriate for audiences of all ages due to the lack of a film rating system. Additionally, it can be observed from the above table that with the exception of name-calling, most of expletive interjections, curses, adjectival modifiers, adverbial modifiers, emphasis, and idiomatic swearing are either de-sweared or omitted in the subtitles. It seems that name-calling is the only function that is retained to a large extent from the original. This result can be explained by the functions of name-calling in the film as they are crucial for the characterisation of the protagonist Jerico, and thus it is important to retain this function in the TT.

The next section investigates to what extent and in which ways the original effects of swearing are retained in the Chinese subtitled film by taking into account the effects of semiotic interplay between subtitles and non-verbal elements in the film. Since there is a clear tendency to tone-down and due to the length of this study, primary attention is paid to the instances where the swearwords are deleted or desweared in the subtitled version.

4.4 An SFL-based multimodal analysis

Using an SFL-based multimodal perspective, this section illustrates how the functions of swearing inCriminal(2016) are achieved multimodally through the three metafunctional levels by adopting multimodal transcription. The aim is to examine the effects of the semiotic interplay on the subtitled version and to investigate to what extent and in which ways the original effects are or can be retained in the subtitled film. While the previous section shows that almost all of the slot-fillers and idiomatic swearing are toned down in the TT, the multimodal analysis demonstrates that the toning-down does not result in the complete loss of the original effects because most of the original functions can still be retrieved from non-verbal elements in the film. Here are some examples:

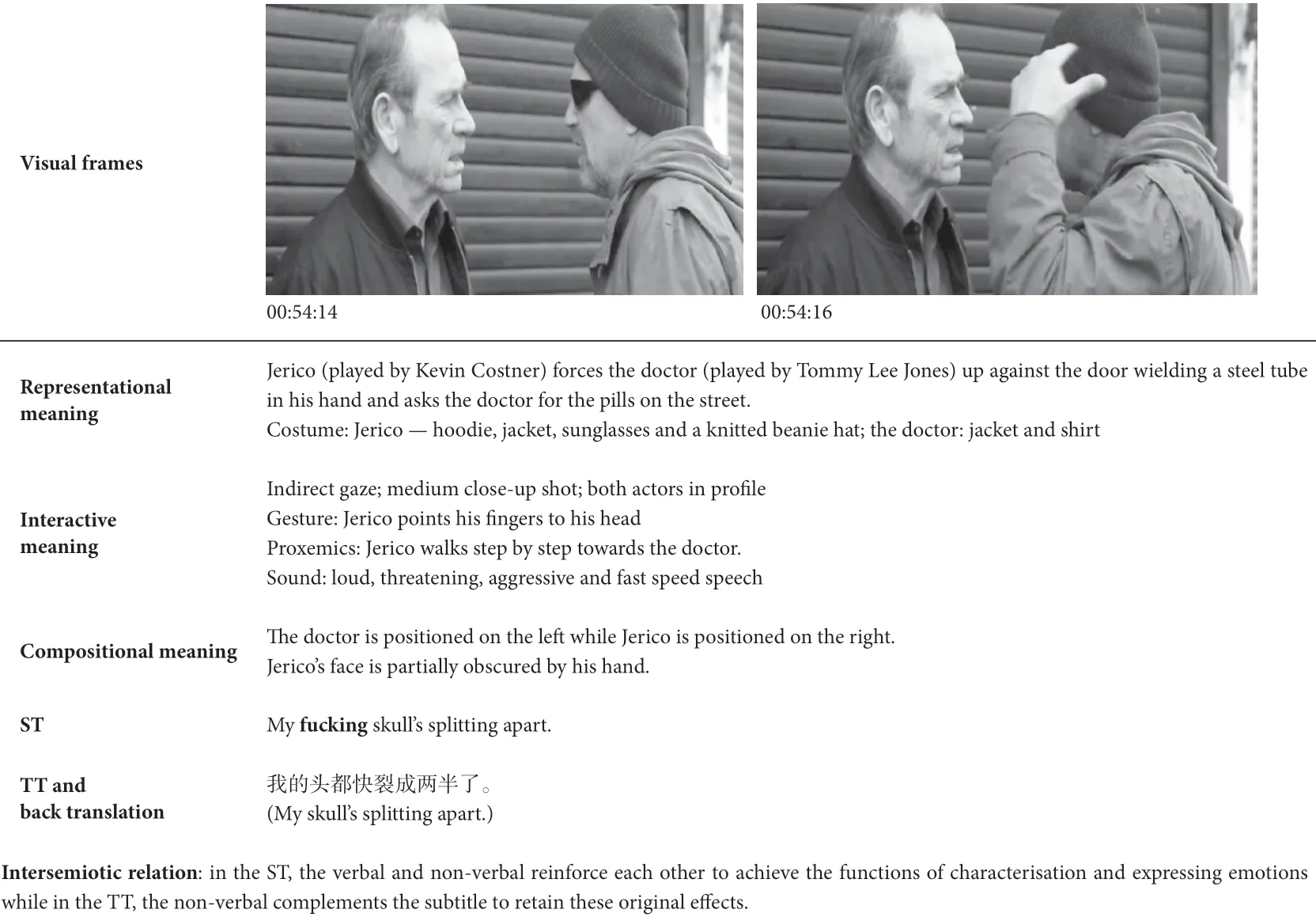

Table 6. The omission of an adjectival modifier

The shot takes place on a street where Jerico uses a steel tube to force the doctor up against the door. He develops a headache after the operation and he furiously asks the doctor to give him some pills to ease the pain. There is a contrast between Jerico and the doctor’s costume contributing to enhancing Jerico’s identity as a dangerous and aggressive criminal. The medium close-up shots allow viewers to clearly see their facial expressions, especially the doctor’s face, Jerico’s gesture, and their relative distance as the doctor looks very frightened when Jerico swears and walks towards him step by step. According to the information value proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), the subject presented on the left is often considered as Given, as the information which is already familiar with the viewers; while the subject presented on the right is New, as something to which the viewers should pay attention and something which is the crux of the message. Here, the doctor is placed on the left which is the information that viewers are already familiar with, while Jerico is placed on the right which can be experienced as a threat. This draws viewers’ attention to his gesture and body movement because these are crucial for the characterisation and expression of his emotions. The aggressive and violent personality of Jerico and his angry emotion are inferred from these non-verbal elements as well as his loud and threatening voice. These functions are also reflected through the verbal as he uses the adjectival modifier ‘fucking’ when he swears. Thus, in the ST, verbal and non-verbal elements reinforce each other to achieve these functions.

Although in the TT, ‘fucking’ is deleted in the subtitle, the original functions can be largely retrieved from the non-verbal elements such as gesture, speech quality, proxemics, and costume as mentioned above. Despite the fact that the verbal element has changed in the subtitled version, audiences can still see the original image and hear the original sound, which contribute to complementing subtitles to achieve the original effects and mitigate the loss of swearing. A similar effect of mitigation is found in the following example of the toning down of idiomatic swearing from earlier in the film:

Table 7. The de-swearing of idiomatic swearing

The shot takes place in a laboratory in the CIA where the doctors are operating on Jerico to implant the memory of the dead CIA agent, Bill, into him. Just prior to this shot, the doctors have found that Jerico’s head is bleeding heavily and he is going to die. They decide to stop the operation immediately while Quaker, the CIA agents’ supervisor, becomes furious and points his finger at the doctors, ordering them to carry on the operation. The phenomenon (the operation) is off-screen which focuses the viewers’ attention solely on the reactor (Quaker) and allows audiences to come face to face with the reactor, emphasising the facial expression and body movement of the reactor (van Leeuwen, 1996). Additionally, the three-quarter front shot shows Quaker’s wide-open mouth and red face in more depth and volume, and a medium shot is employed to show his gesture and body language. Pointing a finger at someone is always regarded as a potent gesture of power and authority since the gesture may force the listener into submission and express the meaning of ‘do it or else’ (Pease & Pease, 2004). It reflects the subject’s personality of aggression, arrogance, and invasion. Here, Quaker’s gesture reflects his dominant status in the CIA and his arrogant personality. As Jay (1999) points out, emotion is always tied in with gestures and facial expressions because they are an important part of emotional cues. Quaker’s anger and fury can be inferred from his gesture, facial expression and high-pitched and loud voice. Furthermore, Quaker is portrayed in the middle of the frames which also reflects his powerful position in the group. The shot also puts the audience in an apparent point of view position, allowing them to experience the threat more intensely. These functions of expressing emotion and indicating authority and power are reinforced by the verbal element—the idiomatic swearing ‘give a shit’. In the TT, although the idiomatic swearing is changed into plain words, the mise-en-scène (e.g. gesture and facial expression), and the soundtrack provide opportunities for complementing the subtitles to convey the emotion and the dominant position of Quaker. The film techniques (e.g. medium shot, lighting and framing) can further draw viewers’ attention to these semiotic resources.

Lastly, an additional contextual factor—co-text, is identified as an element that can provide mitigation for the toning-down of swearing in the TT. Ramière (2010, p. 106) argues that co-text, which she defines as the linguistic environment of the reference, can be a way to provide compensation for the subtitling of cultural-specific references because the target audiences can work out the same implied meaning “through a process of inference, based on the search for optimum relevance/cohesion between the lines of dialogue”. The principle of her finding can also be extended to the subtitling of swearing since co-text is effective in giving audiences information on characterisation, which is the main function of swearing in this film. For instance, although most of the slot-fillers in the ST are changed into plain language in the TT, the function of characterisation can still be inferred from the co-text. In the beginning of the film, when the prison guard introduces Jerico to the CIA agents, he says “Jerico is a very dangerous person” and “He is in and out of prison for half of his life. He has no impulse control and he has a total lack of empathy for anyone or anything”. These exchanges of dialogue are all literally translated in the TT, which is enough for audiences to have a comprehensive understanding of Jerico’s identity as a violent and aggressive convict even if the swearwords are toned down.

5. Genre and register as factors for mitigation

In her systemic functional framework for film semiosis, O’Halloran (2004) suggests that mise-en-scène (the shot) forms the basic analytical unit for the multimodal analysis of film, which is the main focus of the previous examples when examining the mitigation of the loss of slot-fillers and idiomatic swearing. In addition to this, she also signals the importance of taking into consideration the whole film in analysing film semiosis, since the genre or the type of film also have significant influence on the film’s multimodal ensemble. The following section briefly focuses on one factor that transcends shot, namely genre, and its role in the mitigation of the loss of swearing in the TT.

In Film Studies, genre is defined by many factors such as similar themes, characteristic narrative devices, representative dialogue, typical filmic techniques, and recognisable cinematography (Bordwell & Thompson, 2010). These elements are termed genre conventions and are crucial components for genre films. From a multimodal perspective, genre conventions can be divided into different categories: verbal conventions (e.g. dialogue and lyrics), acoustic conventions (e.g. music and sound), and visual conventions (e.g. mise-en-scène and cinematography). As film is a visual medium, visual conventions are of crucial importance for genre films. They can serve important functions in films such as enhancing and facilitating comprehension and interpretation of the narrative as the adoption of those visual codes can “eliminate the need for excessive verbal or pictorial exposition” (Sobchack, 2012, p. 121). Mise-enscène elements such as setting, places, costume, make-up, and lighting “create economically the context and milieu” so that the plot can explain itself with minimal exegesis (ibid.). They can help viewers quickly become familiar with the characters and the plots since it is through the character’s make-up, costume as well as their behaviours that viewers get to know them. Viewers can usually have a general interpretation on their identities and personalities even before they talk. Altman (1996) suggests that, for audiences, genre conventions can shape their expectations and give them clues about what they are about to see and hear.

InCriminal(2016) genre is a considerable factor that provides mitigation for the toning-down of swearing in the subtitles. The film demonstrates the properties of action crime films: there are many visual and acoustic cues embedded in the genre to enhance the likelihood of the use of swearing, such as the rapidity of verbal exchange, the setting and atmosphere established by the use of colour and lighting, the conflict scene, and the physical violence and aggression as shown in the examples analysed before. The following is another typical example containing these non-verbal cues:

Table 8. An example demonstrates the properties of action crime films

This scene happens in an alley where Jerico tries to steal a group of gangsters’ car. The multiple swearwords in the ST create an atmosphere of conflict and violence, whereas in the TT most of them are toned down. However, this does not mean that the original effects are completely lost in the subtitled film since there are many visual and acoustic cues embedded in the genre to provide mitigation for the loss of swearing: the setting in a dark alley, the physical aggression and violence in the fight, the sound of punching and screaming, as well as the rapidity of the verbal exchange. Therefore, the loss of swearing in the TT can be mitigated by these generic conventions as they set up the properties of the exchange and trigger audiences’ expectations of the use of swearing. Although genre is culture-specific, due to cultural globalisation, the dominance of Hollywood cinema in a global context and the increasing import of American films in China, Chinese audiences have gradually become familiar with the conventions and practices in Hollywood genre films as they usually employ universal codes and conventions to appeal to global audiences, meet their recognition, expectations, and interpretation of genre films (Teo, 2012). As a result, audiences who do not speak English may be able to infer that there is more swearing going on than the translations in the light of these generic cues and thereby figure out the intended communicative functions (Greenall, 2011).

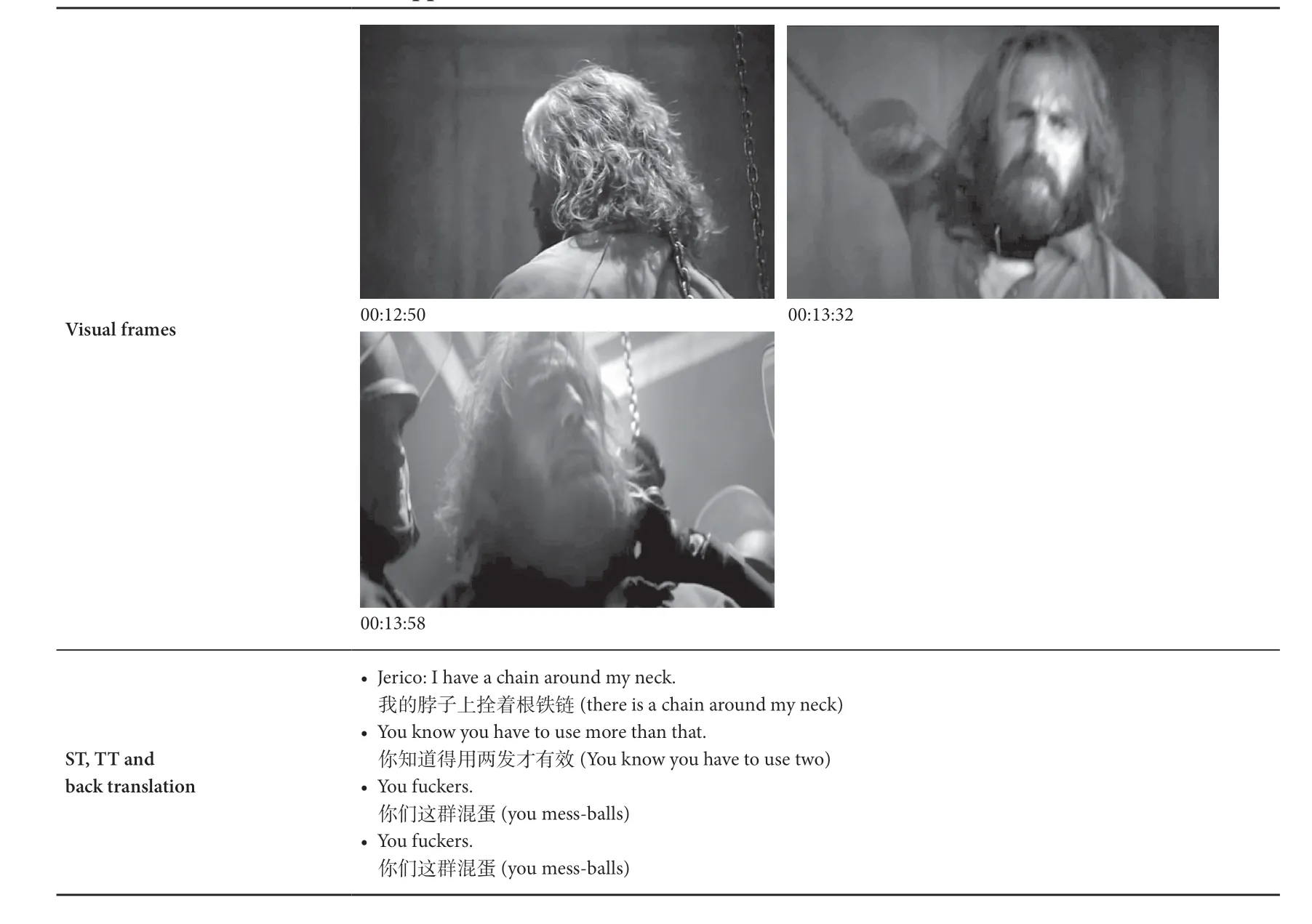

Table 9. The scene Jerico first appears in the film

In addition,Criminal(2016) is an action crime film which is a type of film that promotes the use of swearing due to the conventions of the film’s plot, theme, and characters. The main protagonist of this film is a criminal, a figure usually associated with the use of non-standard language such as swearwords and slang. In Baines’s (2015, p. 14) study, he argues that the register established by the character’s first speech can be a cue for the loss of taboo language in the subtitles since it provides “some measure of the audience’s expectations” of the context. In this study, the results show that the mitigation for the loss of swearing in the subtitled film can be achieved not only by the register established by verbal elements in the character’s first appearance as Baines (ibid.) suggests, but also by the register set up by the non-verbal elements upon the character’s first appearance. Table 9 shows the scene in which Jerico first appears in the film.

This scene takes place in the prison. Visually, the chain, the shadows, Jerico’s costume, and the scars on his face all contribute towards characterisation and creating a dangerous atmosphere. The lowkey lighting emphasises the threatening and mysterious atmosphere. Additionally, Jerico’s violent and aggressive nature can also be inferred from his behaviour as he tries to unlock the chain and attack the police. Acoustically, the sound of chain and the sinister background sound enhance the portrayal of Jerico. More significantly, the repeated translation of ‘fuckers’ into the Chinese swearword混蛋(messballs) establishes the register of his speech. Therefore, through both the verbal and non-verbal elements, the initial presentation of Jerico sets up the use of swearing as a feature of his speech and establishes his identity as a violent and aggressive criminal. Although most of the swearing in his subsequent speech is toned-down in the TT, the register of his speech has already been established by his behaviour and speech on his first appearance. Consequently, the loss of swearing in the rest of the TT can be mitigated by the register established on the character’s first appearance, both verbally and non-verbally.

This argument can be further supported by Guillot’s (2012) application of Fowler’s Theory of Mode (2000) to subtitling as she suggests that subtitles have their own system of multimodal representation, and it is necessary to account for subtitles beyond their face value and take into consideration the multimodality of text when analysing the deletion or reduction in subtitles. The main principles of the theory, such as considering modes as ‘categories of experience’, make it heuristic to explain that several cues in subtitles have a potential to sensitise audiences to the occurrence of specific linguistic or cultural references (ibid, p. 32). In this light, it can be said that several swearwords in subtitles are enough to activate audiences’ knowledge about the register of the speech as there should be more swearwords in the dialogue. Guillot’s (2012) application of this theory to subtitling provides helpful insights into how different verbal and non-verbal cues work in an integrated way to trigger audiences’ experience of the use of swearing, and thereby enable the functions of swearing in the ST to be activated in the TT.

6. Discussion and conclusion

By comparing the ST and the TT, a strong tendency to tone-down is identified, as nearly two thirds of the instances of swearing in the ST are either deleted or de-sweared in the TT. The reasons for this toningdown can mainly be drawn from two aspects: the characteristics of film subtitling, and the taboo nature of swearing. First, due to technical constraints in subtitling, linguistic features such as phatic expressions and slot-fillers are more likely to be dropped in the subtitles because they do not often carry literal meanings, and consequently more space and time are given to the words with literal meanings. Second, the shift of modality from oral to written text also makes it difficult to retain swearwords in subtitles because such words may become more overt and taboo in written text than in oral text. Furthermore, due to the semiotic redundancy resulting from the semiotic complexity in filmic text, non-verbal elements in film can provide audiences opportunities to infer the functions of swearing. O’Sullivan (2013) suggests that the semiotic complexity of multimodal text should be considered as a resource instead of a challenge to translators, which is in line with Pedersen’s (2005, p. 13) argument, “The greater the intersemiotic redundancy, the less the pressure for the subtitler to provide TT audience with guidance”.

Due to the various constraints in subtitling, omission is sometimes inevitable. However, this does not mean that some degree of the original effects cannot be retained in the subtitled film. As Ramière (2010, p. 110) suggests, when analysing audiovisual texts, it is important to analyse the translation techniques from a multimodal perspective rather than at the linguistic level alone since various semiotic modes may offer opportunities for compensation or mitigation and reveal the fact that audiences may not necessarily “l(fā)ose in translation”. From the SFL-based multimodal analysis, the first and most prominent finding which provides evidence for the above argument is that the functions of swearing are multimodally constructed through the three metafunctional levels. In other words, the functions of swearing are not only constructed by the film dialogue alone but through the co-deployment of different elements (e.g. mise-enscène, cinematography and sound). Therefore, translation techniques of omission and de-swearing are not wholly detrimental to the understanding of characters’ emotions and personalities. As a result, the focus of analysis should not only lie on the linguistic transfer of verbal elements alone, but also on non-verbal elements in film, especially their interaction with verbal elements, since they can provide mitigation for the toning-down of swearing in subtitles.

Different from previous studies which are based on a relatively autonomous and decontextualised analysis, this study presents swearing and its translation in relative heteronomy from their context in the multimodal text. From the perspective of multimodality, subtitles are only one element in the whole multimodal ensemble, and it is therefore necessary to treat the whole film as an entire system. In addition to the various semiotic modes mentioned above, there are many other factors that can mitigate the toningdown of swearing, such as co-text as well as the genre of the film and the register set up by a character’s first appearance. The contribution of genre to audiences’ expectations of the use of swearing cannot be ignored because generic conventions are effective in providing information and giving audiences clues about the film’s plot, theme, and characters, which are something that have a strong influence on the dialogue conventions and further influence audiences’ expectations of the use of specific features (Baines, 2015). Many scholars (Kaindl, 2018; Mubenga, 2009; O’Halloran, 2004) have already encouraged researchers to include genre in the multimodal systemic framework because genre is also multimodal, and generic multimodal conventions are effective in triggering audiences’ expectation of the occurrence of certain features such as swearing.

To conclude, existing research which argues that the toning down of swearing has a homogenising effect on the TT cannot be sustained from this study since there are micro (e.g. mise-en-scène, cinematography and sound) and macro factors (e.g. co-text, genre and register) in the subtitled film to cue the functions of swearing. These contextual factors play a more highly important role in AVT than in other forms of translation due to the ‘strong visual and contextual embeddedness’ in audiovisual products (Ramière, 2006, p. 160). As a result, the focus of the analysis of subtitling should not be on what is lost in the TT, but on the effects of these factors on subtitled films and how a certain translation technique can work in a wider context. While loss is inevitable in translation, quite a lot can be retained or kept. There is a need to regard these factors as an integrative component of a functional whole rather than an obstacle in subtitled films. These factors should be considered as resources and help rather than challenges and difficulties in translation.

- 翻譯界的其它文章

- A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China

- The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China

- A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

- Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling

- Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English