Stasis Salience and the Enthymemic Thesis1

Ying Yuan

Soochow University, China

Randy Allen Harris

University of Waterloo, Canada

Yan Jiang

SOAS, University of London, UK

Stasis Salience and the Enthymemic Thesis1

Ying Yuan

Soochow University, China

Randy Allen Harris

University of Waterloo, Canada

Yan Jiang

SOAS, University of London, UK

The argumentative stasis theory and enthymeme principles richly complement each other but they have rarely been investigated jointly. We correct this oversight first with a principled re-analysis of the stasis tradition, resulting in a double-layer stasis system: Cicero’s later system (inDe OratoreandTopica) with “action” stasis’ subclassification, modified by Kenneth Burke’s dramatic pentad of act, scene, agent, agency, purpose (inA Grammar of Motives). Then inspired by Ronald Langacker’s salience theory in cognitive linguistics, we secure two stasis deployment strategies: selection (profile against base) and prominence(trajector against landmark). Stasis theory thus solidified, we examine how it interacts with the two central aspects of the enthymemic thesis: incompleteness and probability and how the enthymemic thesis helps explain the force of stasis theory. This inquiry contributes to rhetorical theory and criticism; argumentation studies; and linguistics, by showing the reach of salience theory.

stasis, enthymeme, salience, Cicero, Kenneth Burke

The connections between stasis theory and enthymemes are firm and sinewy, but they have rarely been noticed in rhetorical theory. There are inklings of connections between them in ancient rhetoric, but only inklings. Cicero’sTopicadefines “a topic as the region of an argument, and an argument as a course of reasoning which firmly establishes a matter about which there is some doubt” (1949, p. 387), where “a course of reasoning” implicates the enthymeme and “doubt” implicates issue or stasis. Nor has modern rhetoric brought them together firmly. Only a very limited number of works touch upon both stasis and enthymeme in modern rhetoric, and even these mostly fail to realize their essential connections. They are both often brought together in writing textbooks, for instance, but without the sense of their natural and reciprocal affinities. In a rather typical treatment, as in Lauer’s excellentInvention in Rhetoric and Composition, they come together almost by accident, little more than items in the same list:

Kairosandstatusas initiators of discourse; special and common topics as exploratory arts;dissoi logoi, enthymeme, example or dialogue as forms of rhetorical reasoning; and probability, truth, or certainty as rhetorical epistemologies. (Lauer, 2004, p. 22)

Bachman (1996), and Crowley and Hawhee (1999/2012), who attach much importance to stasis and enthymeme respectively, still do not demonstrate a clear relationship; the two terms seem to be presented as parallels. But there are inklings of connections in modern rhetoric as well. Brockriede and Ehninger (1960), for instance,link the four “disputable questions” (staseis) with corresponding “claims” of the Toulmin Model (TM), a valuable insight, and Toulmin himself later characterized his model as enthymemic in nature (Jasinski, 2001, p. 206). But Brockriede and Ehninger include the enthymeme among their traditional argumentation “inadequacies”—inferior to the TM, apparently—so the two notions are ships passing in the night. Corbett and Connors (1999),while observing that stasis theory “might help students decide on a thesis” (p. 28), fail to associate their “thesis in a single declarative sentence” (p. 29) with their rigidly structured conclusion-with-reason enthymeme, thus narrowly missing the connection of stasis and enthymeme. They too, like Brockriede and Ehninger, fail to realize the connections they adumbrate.

However, at least two contemporary authors, John Gage and Linda Bensel-Meyers, do understand the stasis/enthymem connections, clearly associating stasis with enthymeme as interwoven elements in essay composition. Gage’sShape of Reason(1987/1991/2001)scrupulously defines an argumentative thesis as “an idea, stated as an assertion, that represents a reasoned response to a question at issue and that will serve as the central idea of a composition” (2001, p. 46). “[Q]uestion at issue”, of course, is a stasis, and “a reasoned response” he makes clear a few pages later, is an enthymeme. “At this point,” he says, “we need a name for the relationship created between a reason and a conclusion.I will call this combination of assertions an enthymeme, a term adopted from classical rhetoric” (ibid., p. 58). Deeply influenced by Gage (as shown in the acknowledgements), Bensel-Meyers’sRhetoric for Academic Reasoningpresents an even more definite connection of the two terms:

Drawing from classical stasis theory, this text shows students how they can use the enthymeme to identify what is discipline-specific about the questions specialists ask about their subject and how these questions control the type of reasoning the specialists use to arrive at answers.(1992, p. xiii)

This captures Bensel-Meyers’s defining approach perfectly. The enthymeme as a thesis statement, blended consistently with a particular kind of stasis, constitutes the most outstanding feature of this writing textbook. However, neither Gage nor Bensel-Meyers takes the intersection of enthymeme and stasis far enough. They are both still a bit too restrained in scope—very likely due to the narrow monolayer stasis system they share (there are no substaseis in their texts), and perhaps to the equally narrow, conclusion-plus-one premise enthymeme structure they share with scholars like Corbett and Connors.2When both staseis and enthymemes are approached theoretically, however,not just in prescriptive writing textbooks, the nature of their connections become far more apparent.

In serious stasis studies, from Hermagoras and Cicero to Crowley and Hawhee (perhaps our finest modern stasis theorists), the canonical four staseis are generally subdivided so as to pin down more specifically the point at issue (though, as always in scholarship,there exist disputes about those subdivisions). Stasis subdivision results in at least two layers of staseis, which means that not only staseis of “fact”, “definition”, “nature”, and “action” in the first layer can trigger inquiry, but their substaseis in the second layer also trigger inquiry. Importantly, each subdivision can lead to corresponding enthymemes.Often, it is a more specific substasis that actually kindles the thesis/enthymeme of the argument. As regards the form of enthymeme, Gage and Bensel-Meyers both—while not failing to recognize flexibility—concentrate on the rhetorical syllogism of conclusion with minor premise (probably for the convenience of composition instruction), leaving other potential forms in a quite dim background, hard to discern. According to Aristotle’s direct and indirect statements on enthymeme in theRhetoric, there exist many more forms of enthymeme beyond the conclusion and minor premise structure. So, the response to the issue at hand may present itself in various ways, the choice of which depends on better suiting the particular rhetorical situation. In short, we are not here to discount the admirable work of Gage and of Bensel-Meyers, but to extend their unification of enthymemes and staseis by broadening their concepts of both.

We extend Gage’s and Bensel-Meyers’s constructive partnership of stasis and enthymeme through a demonstrated two-layer stasis system, and a richer sense of enthymeme variety.

1. Staseis: Number, Naming, and Order

“Stasis” has been defined in a variety of ways due to different focuses. Fahnestock and Secor (1983), for an exemplary instance, offer a succinct, division-centered definition as “a taxonomy, a system of classifying the kinds of questions that can be at issue in a controversy” (p. 137). However, there are disagreements about the taxonomy, disagreements on the number, the naming, the order, and the subdivision of staseis. As regards number, most theorists stick to Hermagoras’s four, but it is not difficult to find variation. Some rhetoricians scale down (Corbett and Connors (1999), for example, accept the three staseis of fact, definition, and quality, leaving action out); others scale up (Gage (2001) has six, the two extra being interpretation and consequence). We hold that four staseis are more reasonable, as they cover all the major issues possibly arising from any phenomenon with clear distinctions between themselves, especially when a second layer opens up the range. Corbett and Connors’s discarded stasis, action, is not only constructive for dealing with a law case, but also in the tackling of other cases such as the “intellectual jurisdiction” substantially illustrated by Alan Gross (2004). And expansions of the stasis taxonomy are inevitably redundant. Gage’s “Interpretation”, for instance, is similar to “definition” and to “value,” as Gage himself acknowledges (2001, pp. 42-43); and his “consequence”, focusing on cause and effect, easily folds into the stasis of “fact”.

As for the naming, all four staseis are associated with different terms of similar meanings: “fact” might be “conjecture” or “inference”; “definition” can be “interpretation” or “designation”; “quality” shows up as “nature” and “value”; “action” is known as “policy”, “procedure” and “jurisdiction”—to give a non-exhaustive survey. We adopt “fact”, “definition”, “nature” and “action”, as these concepts are more direct and widely applied than their alternatives and they have also long appeared in the translated works of Cicero’sDe Inventione,TopicaandDe Oratore.3

The order of the staseis is less controversial, usually following a movement from fact to action. The first three staseis, in particular, follow a logic of occurrence, denotation,and context, as Kennedy (1994) lays out:

the fact at issue, whether or not something had been done at a particular time by a particular person: e.g., Did X actually kill Y. …

the legal “definition” of a crime: e.g. Was the admitted killing of Y by X murder or homicide. …

the “quality” of the action, including its motivation and possible justification: e.g., Was the murder of Y by X in some way justified by the circumstances … (Kennedy, 1994, pp. 98-99)

Each stasis depends in a fundamental way on agreement about the logically prior stasis. First, one wants to know, did something happen; if it did, what should we call it; if it did and we have a name for it, what are the contextual factors that give its fuller meaning. The next move, for action, is equally natural: given this fuller meaning, what should we do about it.4Variations of order, however, also exist, in both ancient and modern works, sometimes even in the same text. For instance, in Cicero’s DeOratore(1942) they are often arranged as fact, nature, definition, action, but not always5and in Voss and Keene (1995, p. 664) we get fact, definition, action and nature (or, using their terms, fact, interpretation, policy and value). If a phenomenon is only probed through one stasis, the order may make little difference, but with more issues covered in the exploration, the sequence itself is meaningful. For Hermagoras, concerned with lawsuits, the order of necessity and importance for arguing is as above; other situations may prefer or even require different orders.

2. Cicero’s System of Staseis

Research on subdividing staseis is relatively sparse. Among the ancients, Cicero takes precedence. Hermagoras, Hermogenes and Cicero all discussed the topic in some detail. The former two, however, are concerned primarily with forensic rhetoric (and Hermagoras’ work is unfortunately not extant). Cicero goes beyond legal realms, but his stasis taxonomy needs some reconstruction. It is scattered among several of his works, especiallyDe Inventione,De OratoreandTopica. The one serious subdivision in contemporary rhetoric, Crowley and Hawhee’s, hews closely to the Ciceronian system for the first three; diverging only with their fourth. Cicero’s discussions on stasis are a rich and solid foundation for any further investigation, but those scattered elusive remarks have not been assembled yet to form a complete intelligible picture. In what follows,we first distil Cicero’s complicated systems of staseis and subdivisions from his work,in partial support of Crowley and Hawhee’s modernization; next, we propose some necessary modifications.

Cicero’s stasis subdivisions evolved between his early work,De Inventione, and his later treatises, especiallyDe OratoreandTopica, which bear much similarity to this topic. The subdividing of the stasis of “fact” shows a particularly wide divergence.De Inventioneuses a rather simplistic time-based criterion, Cicero saying that

the dispute about a fact … can be assigned to any time. For the question can be ‘What has been done?’e.g. ‘Did Ulysses kill Ajax?’ and ‘What is being done?’e.g. ‘Are the Fregellans friendly to the Roman people?’ and what is going to occur,e.g. ‘If we leave Carthage untouched, will any harm come to the Roman state?’ (1949, p. 23)

That is, the young Cicero subdivides “fact/conjecture” into the tripartite categorizations of “past”, “present” and “future”. But the mature Cicero comes to regard this subdivision as both too broad (in terms of time) and too narrow (in terms ofonlytime); essentially, he drops the temporal dimension as an explicit criterion of categorization. In his later work, he offers the following subdivisions: “existence” (which incorporates all three time dimensions), “origin”, “cause” and “change”. InTopica, he says

There are four ways of dealing with conjecture or inference: the question is asked, first whether anything exists or is true; second, what its origin is; third, what cause produced it; fourth, what changes can be made in anything. (1949, p. 445)6

For each substasis an example is offered right after to illustrate its meaning and application. But most examples refer to different things; it would be more illustrative if they all revolved around one thing or one phenomenon.

For “definition”, Cicero’s classifying also evolves considerably afterDe Inventione,where he focuses on “by what word that which has been done is to be described” (1949, p. 23); in the following lines, he decomposes that phrase and suggests that there are two realizations, the actual word and the description, each of which may occur independently.So, only two subdivisions of definition are provided. InDe Oratore, however, Cicero drops the “name” dimension altogether and transfers focus to the differences of “description”. Crassus says

[D]isputes as to definition arise either on the question of what is the conviction generally prevalent, for instance supposing the point under discussion to be whether right is the interest of the majority; or on the question of the essential property of something, for instance is elegant speaking the peculiar property of the orator or is it also in the power of somebody beside; or when a thing is divided into parts, for instance if it is asked how many classes there are of things desirable, for example are there three, goods of the body, goods of the mind, external goods; or on the problem of defining the special form and natural mark of a particular thing, for instance supposing we are investigating the specific character of the miser, or the rebel, or the braggart. (1942, p. 91)

These four subdivisions can be summarized simply as “conviction”, “essence”, “parts” and the last as “mark”, each bringing increased specification in place of his former term, the rather vague “description”. InTopica(1949, p. 447), the subdivisions of “definition” are almost the same.7

The subdividing of “nature” inDe Inventioneis a modification of Hermagoras’s subdivisions, “deliberative, epideictic, equitable, and legal”. Cicero picks up the last two of “equitable” and “l(fā)egal”, and abandons the other two as illogical (1949, pp. 25-31). But his views change. Cicero eliminates the domain characteristics of “equitable” and “l(fā)egal” in favour of a methodological approach. Nature can be argued simply or comparatively. InTopica, he frames the subdivision this way:

When the question is about the nature of anything, it is put either simply or by comparison;simply as in the question: Should one seek glory?—by comparison, as: Is glory to be preferred to riches? (1949, p. 447)

Cicero further specifies “three kinds of subjects” when putting the question simply (or, as we prefer, directly, since he really means by direct, not comparative, metrics):sought or avoided, right or wrong, honorable or base; and two kinds for putting questions comparatively: on the basis of sameness / difference, or on the basis of superiority /inferiority (1949, p. 447). InDe Oratorehe expresses the same opinion (1942, pp. 91-93).

With the stasis of “action”, the divergence between his two stages of works is perhaps the greatest. InDe Inventione, Cicero remarks that this stasis arises when

the question arises as to who ought to bring the action or against whom, or in what manner or before what court or under what law or at what time, and in general when there is some argument about changing or invalidating the form of procedure. (1949, p. 33)

That is, he gives us “person”, “manner”, “court”, “l(fā)aw”, and “time” as the subdivisions of action. InDe Oratore, it is quite different. Crassus says here that

[t]hose referring to conduct either deal with the discussion of duty—the department that asks what action is right and proper, a topic comprising the whole subject of the virtues and vices—or are employed either in producing or in allaying or removing some emotion. (1942, p. 93)8

InTopicathe author expresses the similar subdivisions (1949, p. 449) to those of Crassus, which we may tersely extract as “duty” and “emotion management”.

Table 1 summarizes our discussion and puts the early and late Ciceronian stasis systems side by side for comparison. We engage these systems, with a recognition of Cicero’s greater maturity and rhetorical sophistication in the later system, as a solid base for our modification.

Table 1. Cicero’s systems of staseis and subdivisions

3. A Modified System of Staseis’ Subdivisions

Cicero’s evolved system of stasis subdivisions shows his sustained efforts made for the applicability of stasis theory to all the three kinds of speeches—forensic, deliberative,epideictic—while the use to which Crowely and Hawhee put that system shows its continued relevance. However, the system is not without its problems. Some subdivisions,in particular those for action, remain hard to understand and deploy. We propose now to revise the less manageable of the substaseis and to justify further the ones which we believe should be maintained as they are. Crowley and Hawhee’s adapted (later)Ciceronian system of substaseis is especially valuable to us in this exercise, and we will refer to it often.

For the stasis of “fact”, Cicero’s later subclassifications were widely accepted in his time. They are obviously richer than those of his earlier model, so (with Crowley and Hawhee) we adopt them in whole. They provide straight but rich avenues of invention.Take (as adapted from examples inTopica) the issue of “academic cheating”. Concerning “existence”, a rhetor may position herself on either side of the question, “Is there really any such thing as academic cheating?” The substasis “origin” might be realized with respect to the question “Can academic cheating be traced back to the human nature of greed?” For “cause”, “What conditions have produced academic cheating?” And for “change”, “Can academic cheating be eliminated?” This last question points to something not often noticed in stasis questions, the fact that there might be multiple directions which could follow from such a question, not just pro or con, but degrees of endorsement or rejection. For instance, Can it be ameliorated? Will it get worse? Can we virtually stamp it out, but there will always be a residue of dishonesty? Will it worsen until it hits a certain threshold? And so on. Also, a clear distinction between origin and cause is implicated by these examples. “Cause” means for some factor (whether agentively or non-agentively) “to effect, bring about, produce, induce, make” some occurrence or product, while “origin” is “that from which anything originates, or is derived; source of being or existence; starting point”.9

With “definition”, Cicero replaced “name” and “description” with the broader and more concrete set of substaseis, “conviction”, “essence”, “parts”, and “mark”. We (presumably with Cicero) think these four substaseis are complementary, easier for all to understand and apply, and functionally more effective. Let us apply it to the very term,“stasis”, for example. The “conviction” for stasis (a cited definition in Jasinsky’sSourcebook)can be “a taxonomy, a system of classifying the kinds of questions that can be at issue in a controversy” (Fahnestock & Secor, 1983, p. 137);10the “essence” of stasis is that the issues should be the real ones agreed upon by the participants (actual or imagined); the“parts” of stasis are individual embodiments, in this case (somewhat recursively), “fact”, “definition”, “nature” and “action”; and the “mark” for stasis is a question, direct or implied.

Crowley and Hawhee shift the second substasis of definition, “essence”, into a question of genus, suggesting that it asks “To what larger class of things or events does it belong?” (1999, p. 50). For “stasis”, on this approach we might call it “a strategy of invention”. However, this question is very often answered in “conviction” phase, as Fahnestock and Secor do when they define “stasis” as belonging to the category of taxonomies; indeed, as Crowley and Hawhee do when they define “stasis” as a “means of invention” (1999, p. 44). Further, the genus/differentia method, as a way of defining, may not suit any number of cases, while the explanation of essential property is widely applicable. Crowley and Hawhee also give up the last substasis of definition, “mark”, perhaps because of the difficulty in identification it can present. However, it is rarely difficult with pointing out a characteristic and relevant mark of physical objects; that’s why synecdoche is such a common strategy for labeling (“all hands on deck”, “hundred heads of cattle”, “new set of wheels”). Even for abstract concepts, it is often tractable. With “stasis”, for instance, a typical and relevant mark is the question. In short, all four of Cicero’s later substaseis of “definition” should be retained.

With regards to “nature”, we are with Crowley and Hawhee in fully adopting “direct judgment” and “comparative judgment”. Cicero’s early subdivisions of “equitable” and “l(fā)egal” apply mainly to law cases, and concern only one dimension of direct judgment, while his two later classifications of “direct judgment” (questions put simply on the nature) and “comparative judgment” (sameness or difference, superiority or inferiority) cover two dimensions and suit all kinds of cases. We also accept the two substaseis and would chiefly follow Cicero’s related explanations in applying them.

For the fourth stasis of “action”, Cicero’s later divisions ofdutyandemotion managinggo beyond his earlier substaseis, which are confined to legal speeches. But the two terms are rather broad and unfortunately vague; as such, they are not convenient for modern application. Crowley and Hawhee bravely try to remediate Cicero here,designing their own set of subdivisions, eight in all, in a 2x4 matrix. There are four main questions for deliberative issues, four for forensic.11They warrant their main division by noting that “a rhetor who wishes to put forward a question or issue of policy must first deliberate [i.e., it is first a deliberative matter] about the need for the policy and then argue for its implementation [where it becomes a forensic matter]” (1999, p. 51). We agree strongly with Crowley and Hawhee that Cicero’s substaseis of “action” need remediation, but their scheme misses the mark. To our eyes at least, there is overlap between their two groups of questions (for instance with their deliberative questions “How will the proposed changes make things better? Worse?” and their forensic questions “What are the merits of competing proposals? What are their defects?” (1999, p. 52). But with due respect, and laying aside whatever the merits might be in their project,there are two further defects in their proposal that sink it. First, it is just too complex. It frankly seems very difficult to follow such an elaborate list, possibly excepting the designers themselves. But, secondly, there is already an incredibly robust and valuable set of inventive categories/questions for the stasis of “action”, five of them. The set was unavailable to Cicero, perhaps invisible to Crowley and Hawhee (file this under “Hiding in Plain Sight”) but widely available in textbooks across the land: the five points of Kenneth Burke’s pentad introduced inA Grammar of Motives, “act”, “scene”, “agent”, “agency” and “purpose” (1969, p. xv).

Since the pentad “involves what Burke feels is a fivefold viewpoint of anything whatever that a man can discuss” (Fogarty, 1959, p. 62), one might ask why we assign its terms to the “action” stasis, rather than any of the other three, or to all of them crosssectionally. A fuller answer would take us too far afield, but the short answer is that action is both the nexus of argumentation and the nexus of Burke’s rhetoric. On the first front, all arguments point inevitably to action. Forensic arguments, for instance,which orient to guilt or innocence concerning past events come down to what must be done with the accused, what action results from the verdict: release or conviction. And epideictic rhetoric orients to belief and values at the present moment. Values fuel belief and belief is a predisposition to action; that is, in Thomas Hill Green’s phrasing, belief is “incipient action; or, more properly, it is a moral action which has not yet made its outward sign” (1886, pp. 96-97).12On the second front, as Burke tells us inThe Rhetoric of Religion, the whole dramatistic vocabulary, dramatism itself, is a “vocabulary of action” (1970, p. 23).

The fivefold viewpoint, in perfect consonance with stasis theory, can be seen as “five questions to ask about any topic or problem” (Fogarty, 1959, p. 62), which leads us to replace Cicero’s “action” substaseis, rather than with Crowley and Hawhee’s sensitive but overly elaborate scheme, with the more applicable, systematic, and critically robust“act”, “scene”, “agent”, “agency”, and “purpose”. Our main move is simply to shift the past tense13of critical examination into present tense, or, if the future, into the hortative mode (not what actionwilloccur, for instance, but what actionshouldoccur). Under this slight adjustment, “act” is almost wholly equivalent to Cicero’s “duty” (what act is being performed with respect to the appropriate act; or, simply, what act should be performed).“Scene” is where and/or when the act occurs or should occur. “Agent” is what person or people, or kind of person, kind of people carry out, or should carry out the act, including,as it does for Burke, “co-agents”, “counter-agents”, “personal properties” (“ideas”, “the will”, etc.). “Agency” encompasses the “means or instruments”, which could be understood flexibly, including measures, proposals, programs, etc., for carrying out the act. “Purpose”, is the “why” of an act, the objective or anticipated result.14

Our Burkean set of substaseis for “action” is more definite and applicable than Crowley and Hawhee’s complex set and certainly than Cicero’s impoverished set, in legal as well as in non-legal cases. Their interpretation is flexible: with a law case, one might question if the very trial (act) itself is justified; if this is the right court and ocassion(scene) to conduct the case; if the judge or jury (agent) is qualified to try the case; if the procedure (agency) is appropriate to the trial; or what the “purpose” is of conducting the trial at all. In non-legal arguments, one might argue for or against a certain task (act);when and where to perform the task (scene); who should perform it (agent); what means should be used to perform it (agency) or what objective to be fulfilled (purpose). Table 2 summarizes what we have maintained and what we have remediated with respect to Cicero’s subdivisions.

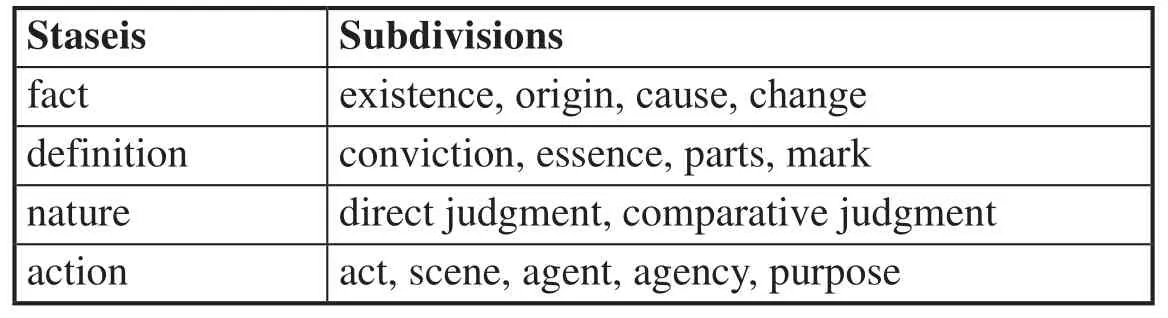

Table 2. A modified system of substaseis

Our neo-Ciceronian system of substaseis helps quickly to locate a significant specific issue existing between different parties in a specific situation and to determine the other substaseis for the support. Without subdivisions, the search for conflicting issues is confined to the general staseis of “fact”, “definition”, “nature” and “action”, a good starting point, to be sure, but handcuffing in its generality.

4. Stasis Salience Strategies

The stasis system offers us a framework for the searching of appropriate questions, but often it is unnecessary to address all the staseis and substaseis; nor, we know, need there be a one-to-one correspondence between a given issue and the stasis with which to argue it. Quintilian cites the two famous defences of Milo on this front:

[T]here is at times some doubt as to which [stasis] should be adopted, when many different lines of defence are brought to meet a single charge; ... I may say that the best [stasis] to choose is that which will permit the orator to develop a maximum of force. It is for this reason that we find Cicero and Brutus taking up different lines in defence of Milo. Cicero says that Clodius was justifiably killed because he sought to waylay Milo, but that Milo had not designed to kill him; while Brutus, who wrote his speech merely as a rhetorical exercise, also exults that Milo has killed a bad citizen. (III.vi.92-94; 1920, Vol. 1, p. 457)15

Here, we see that Cicero defends Milo’s killing of Clodius through “nature” stasis, as signaled by “justifiably”, while Brutus uses “fact” stasis. “In complicated causes,” Quintilian adds, “two or three [staseis] may be found, or different [staseis]” (III.vi.94; 1920, Vol. 1, p. 457).

Crowley and Hawhee explore this point brilliantly with their pedagogical stasis analysis of two contemporary issues, abortion and hate speech. Plotting out the argumentative terrain of each, they trace out potential arguments where the staseis and substaseis lead. Of the former issue, “definition”, they note, “is a crucial stasis in the debate over abortion” (1999, p. 63), while “quality/nature”, they claim, “is a challenging question with regard to the issue of hate speech” (1999, p. 70).

There is also a long tradition of associating staseis with categories of argument.Aristotle inRhetoric(III, xvii) says that his three super-genres of oratory should revolve around different questions; for instance, “In ceremonial speeches you will develop your case mainly by arguing that what has been done is, e.g., noble and useful” (1954, p. 211). The orator, that is, following this precept, will focus on the stasis of “nature” in ceremonial addresses. Contemporary scholars of stasis theory, too, often continue this tradition of matching categories of argumentation with specific staseis. Bensel-Meyers, for instance, matches four classes of academic discourse with their respective characteristic staseis: natural science argumentation orients to the “definition” stasis, political science to “action”, literary and philosophical argumentation to “nature”, the stasis of values, and the argumentation of the disciplines in her history/economics/psychology matrix to “fact” (1992, p. 17).16This tradition reflects the ways in which issues and perspectives habituate to discourses, and deeper drilling into these discourses would no doubt have to illustrate the workings of the substaseis (which Bensel-Meyers does not provide). Evolutionary biology, for instance, would orient toward the conviction substasis of “definition”—what the morphology evolved todo; in chemistry,the periodic table is a constellation of essences; the Linnaean system is founded on definitive marks.

However one aligns stases and arguments, it is clear that stases often work in concert—firstly, in the stasis/substasis relationship, which Quintilian tells us is synecdochic (“in every special question the general question is implicit, since the genus is logically prior to the species”—III.v.10; 1920, Vol. 1, p. 401); secondly, in the crosssectional deployment of substaseis from different general staseis (“it need disturb no one,” Quintilian reassures us on this front, for instance, “that one law may originate in two [stases]” III.vi.101; 1920, Vol. 1, p. 461). Argumentation is not a matter, despite how pedagogically convenient it might be to pretend the reverse, of a simple one-stasis-oneargument mapping. Crowley and Hawhee’s procedure is especially valuable here, as they analyze all four staseis in both of their causes, abortion and hate speech, with special attention to the reciprocal implications of various staseis and substaseis.

There are, then, two central features of stasis theory that any framework needs to recognize: the alignment of staseis and categories of discourse, and the widespread occurrence of multi-staseis functionality. Together, these features suggest a kind of figure/ground relationship (using the terms of Gestalt psychology), in which stasis theory as a whole is the argumentation ground and specific staseis stand out saliently against that ground. We would extend this strategy, for both rhetorical criticism and rhetorical construction: stasis theory has two layers: the four-stasis complex, against which one stasis takes prominence, and the stasis itself, against which the substasis is defined. The Gestalt terminology, however, while well known and helpful in brief illustrations, will not do for theoretical purposes—in part because it primarily denotes a visual relationship,in part because the wordfigure—central to rhetoric generally and, under the influence of Jeanne Fahnestock’sRhetorical Figures in Science(1999), to argumentation theory,in a radically different and more common meaning—will lead to endless confounding.And while the relationship is theoretically relative, with the figure in principle becoming the ground to a further figure or figures, as the granularity (what Burke called the circumference) changes, it tends to suggest a misleading fixedness. Cognitive Linguistics, however, has adapted the figure/ground concept to language with a new and revealing terminological shift and a layered granularity.

Ronald Langacker, who is most responsible for this adaptation and the terminology,identifies thebase(the scope of a predication) and theprofile(its designatum) of expressions. For example—the sort of simple geometrical example that Langacker favours, for its precision and its cognitive implications—an arc is a two-dimensional curved line. Yet, it cannot beonlya two-dimensional curved line. Anarcpresupposes a base domain, the circle, as its semantic fundament. “[O]nly when a set of points is identified with a portion of a circle,” Langacker notes, “is it recognized as constituting an arc (and not just a curved line segment)” (1987, p. 184). An arc is a profiled section of a (presupposed) circle. Meanwhile, a circle is a profiled section of a (presupposed)otherwise empty space. “The semantic value of an expression,” Langacker says,

resides in neither the base nor the profile alone, but only in their combination; it derives from the designation of a specific entity identified and characterized by its position within a larger configuration. (ibid., p. 183)

One could not ask for a better description of how a given stasis functions against the backdrop issue-field of possibilities stasis theory defines. In our terms, the four-stasis system is the base, and the selected is the profile; their combination helps to better judge or generate the persuasiveness of an argument. We would say, paraphrasing Langacker,that the rhetorical value of an argument resides neither in stasis base nor in the selected particular stas(e)is alone, but in their combination. Langacker’s second layer of salience is established within the profile:

In virtually every relational predication, an asymmetry can be observed between the profiled participants. One of them, called the trajector, has special status and is characterized as the figure within a relational profile.... Other salient entities in a relational predication are referred to as landmarks, so called because they are naturally viewed as providing points of reference for locating the trajector. (ibid., p. 217)

Thus, in a predication like “Marco left the game”,Marcois the trajector, with respect toleave, whilethe gameis the landmark. For stasis theory, among the profiled/selected staseis, only one stasis, in particular, its one substasis relating to a specific claim is a trajector, all the other selected serve as landmark.

To sum up, drawing on Langacker’s two-layer salience theory, profile-base, trajectorlandmark, we justify two stasis deployment strategies: stasis selection (selecting the needed for the topic) and prominence treatment (choosing one as the governing).

5. How Stasis Salience Reveals the Enthymemic Thesis

The enthymemic thesis refers to an argument’s thesis statement which takes the form of“the conclusion of a syllogism in the first clause and the least acceptable premise in the‘because’ clause” (Bensel-Meyers, 1992, p. 124). The second clause is a minor premise; the missing major premise is often assumed to be accepted by the readers.17We agree that the thesis of every article should be looked upon as an enthymeme, in any of several forms.18Often—perhaps most often—an argument will express several standpoints and its author fails to offer a central one at a usual position. In such cases, how do we recognize its thesis? Our layered stasis-salience strategy, we contend, will help quickly to locate the enthymemic thesis, for the prominent stasis among those at work reveals the author’s main point. We know argumentation theorists are not always in the market for new vocabularies. But the notions of (1) a fundamental ground (base) of all staseis against which the selected are figured (profiled), and (2) the sense of the supporting (landmark) to contrast with the leading (its specifically instantiated trajector), can theoretically, critically,and methodologically enrich stasis theory. If we think in these terms, irrespective of our theoretical lexicon, our stasis analyses and our argument invention will both be more potent.

Abraham Lincoln’s well-known and remarkable ten-sentence Gettysburg Address is an excellent case in point. Because of its brevity, we reproduce it (in the standard Bliss version) in its entirety.

Address at Gettysburg

[1] Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation,conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

[2] Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. [3] We are met on a great battlefield of that war.[4] We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. [5] It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

[6] But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. [7] The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. [8] The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. [9] It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. [10] It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.Using a base of the 4-stasis system, we see that the Gettysburg Address profiles three staseis: “fact”, “nature”, and “action”, with “definition” left out. The first four sentences are about the “fact” of dedication, among which S4 concerns the “existence” of the dedication, S2 and S3 the “cause” (the civil war leading to the loss of lives and this dedication), and S1 the noble “origin”. S5-S8 orient to the “nature” of this dedication via the “direct judgment” (altogether fitting and proper) and “comparative judgment” (S7 and S8). The last two long sentences evince the stasis of “action”. Using our revised pentad substaseis, we see that the “act” has the part of “the unfinished work … the great task remaining before us”; that is, the carrying out of the on-going civil war. “Scene” is the repeated “here” and the implied “now” to stress the urgency of the act. As to “agent”, the reiterated “us/the living” and “we” demonstrate who will carry on the act, but we may understand these flexible terms either narrowly as the government and its army, or broadly, as all people supporting this war. “Agency” can be identified as “be dedicated to”, “take increased devotion”, and “highly resolve”. “Purpose” is the most elaborate of all these substaseis, represented by three specific aims: “that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

“Action”, then, is the prominent stasis (trajector) in contrast with the other two selected staseis (landmark); it plays the governing role in the Gettysburg Address. For comparatively, it occupies more space than either “fact” or “nature”; all its five substaseis are covered, forcefully or substantially; and the flurry of three aims occupies the location of the greatest salience, the very end of the address. The enthymemic thesis of the speech,therefore, should be closely related to the “action” stasis, which can be extracted from S9-S10: “We should carry on this civil war to the end (the unfinished work/task);” all the other sentences mainly contribute to the minor premise, which can be condensed into “this civil war is for liberty and equality”, with the assumed major premise of “a war for liberty and equality should be carried on to the end”. Combining the enthymemic thesis with stasis salience, especially the prominent stasis, assists us effectively to identify the central point of the discourse.

6. How the Enthymemic Thesis Dominates Stasis Salience

At the productive end of argumentation, once we secure the thesis of the argument, the stasis outline can be worked out; to be specific, the enthymemic thesis statement will determine the stasis salience: the selection of the staseis and the prominent treatment. For example, the following four enthymemic theses19will evince different stasis salience:

(1) One-upsmanship is the root cause of fierce competition.

The thesis itself profiles the “fact” stasis upon the base of all the four staseis, as it offers the “cause” to the “existence” of fierce competition, so this stasis must be deployed fully and prominently, better with all the substaseis (“existence”, “origin”, “cause” and “change”) covered substantially; especially “cause”, the trajector core, which requires the distinction between root cause and other causes, and proportionate illustrations. For the other three staseis,“definition” can be deployed to support the thesis, providing a clear interpretation of the key concept “one-upsmanship”; but the staseis of “nature” and “action” are marginal to this thesis, whether one covers them or not mainly depends on the scale of the argument. That is to say,the stasis other than “fact” may in this case be chosen as profile, but never as trajector.

(2) Bats are mammals not birds.

This enthymemic thesis centralizes the stasis of “definition” (note that this is what Bensel-Meyers predicts, with a ‘scientific’ thesis), putting all of “conviction”, “essence”, “parts” and “marks” into play, in order to fully articulate the definition. Reasonably, “essence”/the essential property of bats (the appropriate minor premise) should be treated as trajector: they do not reproduce via eggs but embryos. Besides the compulsory “definition” profile, one may include the “fact” stasis concerning the “existence” of the confusion and the major “cause” of the mistaking; and one might even touch upon “nature” by comparing such a thesis with the similar claim that “whales are mammals not fish.” The stasis of “action”, however, has little if any role in supporting this thesis.

(3) Supervised group work plays a constructive role in writing instruction.

The enthymemic thesis here profiles the “nature” of the supervised group work, so the argument should revolve around this stasis by illustrating its “direct judgment”, here “constructive”, with typical examples and their analyses; and “comparative judgment” of the contributing advantages engendered from valid cooperation throughout the process, in contrast with the non-supervised group work or with the merely individual work. Of the other three staseis, the “definition” of “supervised group work” can be supportive; a brief introduction of “fact” as to the controversial function of group work in writing might serve as a desirable beginning; the “action” stasis is optional, and can be ignored with the constraints of time or space allocated to delivering the argument. In brief, as profile, there can be one or more staseis chosen, but for this thesis, only “nature” is suitable to be a trajector, its substasis of “direct judgment”, in particular.

(4) A severe policy should be implemented against plagiarism in term paper.

This enthymemic thesis is patently “action”-centered. Logically, the argument should develop around “act”, “scene”, “agent”, “agency”, and “purpose”. Of all the substaseis, “agency” takes prominence (implementing a severe policy in place of a current mild one) and drives the argument most substantially. For the other three first-layer staseis, they are all supportive but need not be elaborated. A “definition” of “plagiarism” is likely necessary, as controversy often arises in regards to criteria; the serious “nature” of plagiarism at the present time is worth mentioning (if time/space provides); statistics about the “fact” of plagiarism on campus, or a compelling example of the “fact” of plagiarism, might bring up the rear stasis invention strategies. So, in this case, while more than one stasis may be chosen as profile, only “action” should be treated as trajector, with its substasis of “agency” as the most prominent.

We don’t mean to suggest that argument construction must have a paint-by-numbers stasis strategy, of course. There are a variety of methods to build an essay outline:brainstorming, branching, six-perspective cubing (description, comparison, association, analysis, application, argument),20syllogistic term developing,21and so on. Each method,favored by different rhetors, undoubtedly possesses unique advantages in tackling certain topics or genres. However, we contend that a stasis salience outline keyed to the enthymemic thesis on its own is powerfully sufficient, and in combination with other methods can enhance them substantially.

7. Conclusion

Our investigation involves three specific inquiries in order to clarify stasis theory,rejuvenate it in a neoCiceronian mode, and link it productively to the enthymeme (by way of the enthymemic thesis). We carried out a focused survey of the interplay traces of the two terms in modern rhetoric and discover that although Gage and Bensel-Meyers have manifestly connected them, the linking they make is still confined due to their one layer stasis system and restricted forms of enthymeme. But the further classifications of the four staseis and the possible forms of enthymeme remain disputable among rhetoricians and other argumentation theorists; thus, it is here that we exert most of our efforts. By comprehensively tracing Cicero’s stasis subcategorizations, we encourage maintaining his reasonable substaseis, across “fact”, “definition”, and “nature”, while replacing his ineffective “action” substaseis, in the light of Burke’s dramatic pentad. With Langacker’s two-layer salience theory, we illustrate the stasis deployment strategies of stasis selection(profile against base) and prominence treatment (trajector against landmark). Combining this stasis salience system with the enthymemic thesis, we show that these two can be powerfully linked: in criticism (discourse analysis), one can identify the thesis by examining the author’s stasis salience strategies (conducted consciously or unconsciously), especially the content of the prominent stasis; and in production, the enthymemic thesis should dominate the choice of the staseis and the prominence treatment of the trajector stasis, so that the whole essay will remain focused and coherent. To carry home our proposals, we put this model to work in both an analysis of Lincoln’s masterful address and the projected invention of argument outlines in four prototypical theses.

Notes

1 This research has been supported by Chinese National Social Science Fund Project: “On Argumentative Textual Functions of Major Tropes and Schemes” (15BYY178).

2 As Bensel-Meyers states most clearly, “anenthymemeorrhetorical syllogism… represents the conclusion of a syllogism in the first clause and the least acceptable premise in the ‘because’clause” (1992, p. 124).

3 Action is perhaps the most variably named of the canonical staseis; “jurisdiction”, “procedure”, and “policy” are almost equally distributed with “action”, largely on the basis ofwhichaction is at issue. If it isargumentativeaction—whether, say, some given evidence is admissible,or whether a given forum is appropriate to hear or adjudicate the argument—“jurisdiction” and “procedure” are preferred. When the action, rather, is the outcome of the argument—whether we should build this bridge or pass that legislation—“policy” is preferred. “Action” more easily encompasses both foci. It is also, as Walsh (2013, p. 230, Note 9) points out, the preferred term in composition studies.

4 Kennedy is rendering Hermagoras’s version of stasis theory, in which the fourth stasis maps more directly into jurisdiction (1994, p. 99) and is therefore orthogonal to the other three.One can argue jurisdiction independent of fact, definition, and quality. Curiously, though, he(following Hermagoras) lists the fourth stasisas the fourth stasis, last. For a more expansive notion of this stasis, in which the action might be of procedure or of outcome, the fourth position is more natural.

5 This order appears in Ixxxi, IIxxv, IIIxix, but in IIIxxx the more frequent order is adopted.

6De Oratoreappears to be in synch. Crassus says that “Reverting to inference, they divide it into four classes, the question being either what actually exists,…or what is the origin of something,…or the cause and reason of things,…or it deals with change,…” (1942, p. 91)

7 He says in Chapter XXII, “When the question concerns what a thing is, one has to explain the concept [conviction], and the peculiar or proper quality of the thing [essence], analyze it and enumerate its parts [parts]. For these are the essentials of definition. We also include description, which the Greeks call (character or hall mark) [mark].” (1949, p. 447)

8 Here, the term “conduct” for the last stasis, replaced with “action” in the context, is an equivalent to “the translative” ofDe Inventione, though they are almost totally different in their respective subclassifications.

9 The distinction is based on the onlineOxford English Dictionary, from which all the quotations are drawn.

10 As we have seen, inDe OratoreCicero thought conviction to be “generally prevalent” (1942, p. 91). But Cicero was no linguist, and we recognize that definitions for some concepts may not be agreed upon, may even be contested. Though it makes no immediate difference to our argument, we feel it more operative to treat prevalence as contingent upon groups, from small to culture-wide, leaving out only an individual semantic conviction (of the Humpty-Dumpty,“glory” sort), which is rhetorically pathological.

11 In our recent revising of the manuscript, we find that in their 2012 Pearson edition, they have listed almost the same questions; just the last question in the (1999 edition) forensic set has been left out.

12 We do not know the exact provenance of this term, “incipient action”—perhaps John Mason Good’s 1805 translation of Lucretius, the earliest usage we could find (Lucretius, III. 255, p.367)—but it was common in 19th century philosophical, theological and chemical discourse.Burke, of course, adapted it from I. A. Richards (Burke, 1969, p. 235).

13 Burke inA Grammar of Motivesexplains his pentad in the past tense: “what was done (act), when or where it was done (scene), who did it (agent), how he did it (agency), and why(purpose).” (1969, p. xv)

14 The phrases and brief quotations in this paragraph are all fromGrammar’s “Introduction: The Five Key Terms of Dramatism” (Burke, 1969, pp. xv-xx).

15 In Butler’s otherwise exemplary translation of theInstitutes, he translatesstatu(and related forms) asbasis. We interpolate the preferred term.

16 Bensel-Meyers has a somewhat idiosyncratic taxonomy of staseis (“Policy”, “Value”, “Consequence”, and “Definition”), which we have translated (where relevant, for expository reasons) into the more common stasis terminology we use throughout this paper.

17 We do not wish to engage the extensive literature on the true nature of the enthymeme. Rather, we will just sketch the interpretation which applies in our current argument. We are with Aristotle, mainly based on his account of the two defining traits: “abbreviation” and “probability”. The former is perhaps more controversial. He describes the feature in these terms:

The enthymeme must consist of few propositions, fewer often than those which make up the normal syllogism. For if any of these propositions is a familiar fact, there is no need even to mention it; the hearer adds it himself. Thus, to show that Dorieus has been victor in a contest for which the prize is a crown, it is enough to say ‘For he has been victor in the Olympic games’, without adding ‘And in the Olympic games the prize is a crown’, a fact which everybody knows. (1954, p. 28)

Many rhetoricians and logicians consider an “incompleteness” to be the very characteristic of enthymeme. Perelman, for example, defines enthymemes as “abbreviated syllogisms” (1979, p. 26). Others, including Bitzer (1959), Green (1995), and Yuan (2006) do not regard truncation to be indispensable, which is the position we adopt here. As to “probability”, Aristotle means that compared with the standard syllogism, the conclusion reached through an enthymeme most often displays the character of being probable, as “the propositions forming the basis of enthymemes, though some of them may be ‘necessary’, will most of them be only usually [contingently] true” (1954, p. 28).

18 Based upon the in-depth investigation of Aristotle’s related remarks and illustrations as well as Cooper’s (1932) “Introduction” to his translation of theRhetoric, Yuan (2006) first justified 7 forms of enthymeme/rhetorical syllogism from the complete form with all the three propositions to the omission of one or two propositions. Most popular, perhaps, is the twoproposition enthymeme of conclusion plus minor premise.

19 To be concise, here we construct all the theses in the form of one proposition enthymeme which has been proved to be one type of the 7 rhetorical syllogisms in Yuan (2006).

20 These methods are summarized from Shouhua Qi (2000)Western Writing Theories,Pedagogies, and Practices.

21 This method is from Bensel-Meyers (1992), outlining argumentation mainly around the three syllogistic terms and their interrelationships in the enthymeme.

Aristotle. (1954).Rhetoric(W. R. Roberts, Trans.). New York: Random House.

Bachman, S. O. (1996).Whose logic? Which theory of argument? Introduction and assessment of the Hintikka interrogative model for the teaching of argumentative writing with comparisons to the Toulmin model, stasis theory and ‘traditional’ logic(Dissertation, The Florida State University).

Bensel-Meyers, L. (1992).Rhetoric for academic reasoning. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Bitzer, L. F. (1959). Aristotle’s enthymeme revisited.The Quarterly Journal of Speech,45(4),399-408.

Brockriede, W., & Ehninger, D. (1960). Toulmin on argument: An interpretation and application.The Quarterly Journal of Speech,46(1), 44-53.

Burke, K. (1969).A grammar of motives. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1970).The rhetoric of religion: Studies in logology. Berkeley and Los Angeles:University of California Press.

Cicero, M. T. (1942).De Oratore(Book III) (H. Rackham, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cicero, M. T. (1949).De Inventione, De Optimo Genere Oratorum, Topica(H. M. Hubbell,Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cooper, L. (1932). Introduction: Aristotle. InRhetoric(L. Cooper, Trans.). New York: D. Appletoncentury Company.

Corbett, E., & Connors, R. (1999).Classical rhetoric for the modern student. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crowley, S., & Hawhee, D. (1999).Ancient rhetorics for contemporary students. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Fahnestock, J. R. (1999).Rhetorical figures in science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fahnestock, J. R., & Secor, M. J. (1983). Grounds for argument: Stasis theory and the topoi. In D. Zarefsky (Ed.),Argument in transition: Proceedings of the third summer conference on argumentation(pp. 135-145). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Fogarty, D. S. J. (1959).Roots for a new rhetoric. New York: Bureau of Publications.

Gage, J. T. (2001).The shape of reason. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Green, L. D. (1995). Aristotle’s enthymeme and the imperfect syllogism. In W. B. Horner & M.Leff (Eds.),Rhetoric and pedagogy: Its history, philosophy and practice(pp. 19-42). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Green, T. H. (1886).The witness of God and faith: Two lay sermons. London: Longmans, Green.

Gross, A. G. (2004). Why Hermagoras still matters: The fourth stasis and interdisciplinarity.Rhetoric Review,23(2), 141-155.

Jasinski, J. (2001).Sourcebook on rhetoric: Key concepts in contemporary rhetorical studies.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Kennedy, G. (1994).A new history of rhetoric. New York: Oxford University Press.

Langacker, R. W. (1987).Foundations of cognitive grammar(Vol. I):Theoretical prerequisites.Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lauer, J. M. (2004).Invention in rhetoric and composition. West Lafayette: Parlor Press.

Lincoln, A. (1863). The Gettysburgh address. Retrieved from http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

Lucretius, C. T. (1880).On the nature of things(Trans., J. Watson [prose] and J. Good [poetic]).London: Geroge Bell & Sons.

Perelman, C. H. (1979).The new rhetoric and the humanities: Essays on rhetoric and its applications. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Qi, S. (2000).Western writing theories, pedagogies, and practices. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Quintilian, M. F. (1920).Institutio Oratoria(Vols. 1-4) (H. E. Butler, Trans.). Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Voss, R. F., & Keene, M. L. (1995).The heath guide to college writing. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company.

Walsh, L. (2013).Scientists as prophets: A rhetorical genealogy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yuan, Y. (2006). Enthymeme: Kernel of Aristotle’s Rhetoric.Rhetoric Learning,23(5), 23-26.

About the authors

Ying Yuan (szyuanying@sina.com) is teaching in the Department of English at the School of Foreign Languages, Soochow University, China. She received PhD in Western Rhetoric from Shanghai International Studies University and completed Postdoctoral Fellowship at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests are mainly in theory of rhetoric,comparative rhetoric, and rhetorical criticism. Currently she is heading a national research grant project “On Argumentative Textual Functions of Major Tropes and Schemes”. Her books includeTowards a New Model of Rhetorical Criticism(Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2012),Readings in Western Rhetoric(Soochow University Press, 2013),Western Rhetoric: A Core Concept Reader in Chinese Translation(Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2017).

Randy Allen Harris (raha@uwaterloo.ca) is professor in the Department of English Language and Literature, at the University of Waterloo, Canada. His research interests focus on cognitive and computational rhetoric, with a special emphasis on rhetorical figures; linguistics theory, especially the late twentieth century trajectory coming out of Chomskyan theories; voice interaction design; the history and theory of rhetoric; and the rhetoric of science. His books includeThe Linguistic Wars(Oxford, 1994, 2018),Rhetoric and Incommensurability(Parlor, 2004),Voice Interaction Design(Elsevier, 2004), andLandmark Essays in Rhetoric of Science: Case Studies(Taylor and Francis, 1997, 2017).He is the Director of the RhetFig Computational Rhetoric Project.

Yan Jiang (yj9@soas.ac.uk) is lecturer in linguistics and the languages of China at the

Department of Linguistics, SOAS, University of London, UK. He received an MA from Fudan University, a PhD in linguistics from the University of London. His research interests include semantics, pragmatics and discourse, rhetoric, and Chinese grammar.He is author ofIntroduction to Formal Semantics(China Social Sciences Press, 1998),translator ofRelevance: Communication and Cognition(China Social Sciences Press,2008), and chief editor as well as author ofApproaching Formal Pragmatics(Shanghai Educational Publishing House, 2011).

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Wilhelm II’s ‘Hun Speech’ and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I

- The Meaning and Madness of Money: A Semio-Ecological Analysis

- Facebook Engagement and Its Relation to Visuals,With a Focus on Brand Culture

- Contemporary Discriminatory Linguistic Expressions Against the Female Gender in the Igbo Language

- A Socio-Semiotic Perspective on Boko Haram Terrorism in Northern Nigeria

- A Century in Retrospect: Several Theoretical Problems of Russian Formalism From a Paradigm Perspective