A Socio-Semiotic Perspective on Boko Haram Terrorism in Northern Nigeria

Ahmed Umar

Federal University Dutse, Nigeria

A Socio-Semiotic Perspective on Boko Haram Terrorism in Northern Nigeria

Ahmed Umar

Federal University Dutse, Nigeria

Using a multimodal socio-semiotic framework (Bezemer & Jewitt, 2010), this paper examines the terrorist campaign of Boko Haram in northern Nigeria and its impact on the people of the region. The terrorists have been shown to deploy physical weapons like knives and firearms,along with psychological ones like multimodal socio-semiotic propaganda to target society,both materially and psychologically. Their ultimate psychological weapon is death, encoded in multimodal signs (Kress, 2010). The targeted society tends to respond to that prompt of death with fear, which in turn serves as another prompt to various attitudinal, conceptual,and practical changes within that society. The overall socio-semiotic link between terrorist campaigns and social control rests on that major terrorist prompt of death, and fear remains the dominant social response (Van Leeuwen, 2005). The moment the targeted society ceases to recognize that prompt, or that prompt loses its intended social responsive value, terrorism in that society will not continue to survive.

multimodal sign, socio-semiotic, interpretant, terrorism, prompt, response

Introduction

No proper understanding of the current Boko Haram crisis in northern Nigeria can be attained without looking at it in a holistic historical overview. The northern part of Nigeria is more diverse than the southern part, with a larger variety of languages (Dudley,1968). This variety can be said to consist of over 280 languages/dialects. The dominant languages of the region are Hausa, Fulbe, and Kanuri. Each of these three languages has a large number of words borrowed from Arabic, which is generally attributed to three main routes (Davies, 1956; Ellis, 2002): (i) the origins of those languages, over one thousand years ago, having Arabian roots [Afro-Asiatic]; (ii) ancient trade interactions with Arabia;(iii) the introduction of Islam to the region, especially in Kanem-Bornu (present day Borno and Yobe states).

Due to its greater geographical proximity to and other socio-cultural assimilations with Arabia, Kanem-Bornu (in the present day, birth place of Boko Haram) happened to be the first Nigerian region explored by Arabs and introduced to Islam (Trimingham, 1962). The history of Islam in Borno dates back to over 1000 years ago (Davies, 1956),and the founder of the Kanem Empire, Sheikh El-Kanemi, was an Arab. In fact, the name of theKanurilanguage is a blend of the wordsKanemandri(area, source); that is,kanu+ri= ‘Kanem area/source’.

The Hausa language is generally believed to have originated from one of three sources(Ahmed & Daura, 1976): (a) marriage of a Baghdadi Arab, known as either Abu Yazid or Bayajidda, to the queen of Daura, Daurama, a source that reflects the Arabic/Berber migrations via North Africa to the Sub-Saharan/Sahelian region (1000AD – 1400AD); (b)the myth or fable that the Hausa migrated fromHabasha(Ethiopia), an origin eventually modified toHausa(the language); (c) yet another fable that the ancient father of the Hausa people was a man who came to Daura ‘riding an ox’ (in Hausa,hau sa).

The socio-cultural marriage of Hausa and Fulbe existed for many years before the Danfodio Islamic revivalist jihads ushered the religion of Islam across the Hausa land on a scale similar to the spread of Islam in Kanem Islamic empire. The Fulbe, to whose ethnicity Shehu Usman Danfodio belonged, happened to be a nomadic people, who came to Hausa land via Mali and Senegal. Danfodio Islamic revivalism and its empire thus put the Fulbe language on par with, if not in a superior position to, Hausa on socio-political scales. Today, most of the royal lineages in the north have Fulbe roots. Hence, the Hausa people came to be variably referred to asHausaorHausa-Fulani.

With the Kanem Empire in the north-east and the Danfodio Empire across the rest of the north, Arabic thrived both as the medium of writing and as the language of Islamic studies and worship. Therefore, even before the arrival of English in the north via British colonial explorers and missionaries, the Arabic orthography had been used in both Arabic and Hausa writings (the Hausanized Arabic was known asajami).

Socio-culturally and politically, the Kanem and Danfodio Islamic revivalism and their empires have affected all ethnic groups in northern Nigeria (Meek, 1931). The three dominant tribes (Hausa, Fulbe & Kanuri), in particular, have been deeply influenced in a socio-cultural way by Arabic and Islam (Bulakarima et al, 2003; Newman & Newman,1979). Their lingual resources were enriched by Arabic, and their socio-economic and political systems became Islamically oriented.

Hence, when British colonialism reached the northern region of Nigeria, it found a people largely living under a blend of Islamic-customary systems of government (Suberu,2001). Both in the Kanem north-east and the Danfodio larger north, the societies were ruled in part by Islamic laws/codes in areas such as commerce, taxation, marriage, and the judiciary. The British colonialists, who were more interested in imperial and commercial influence than in religious propagation, allowed some form of the then existent polity to continue. Resistant emirs and kings were dethroned and replaced with amenable ones.What is known asindirect rulewas instituted. It was a system that conveniently enabled the British colonialists to govern the northern population via its emirs and kings.

Both in terms of revenue and sovereignty, that indirect rule gradually but greatly weakened the northern emirates and kingdoms (Davies, 1956). The taxes that used to be collected and utilized by the emirs and chiefs came to be re-channelled to British colonial coffers, leaving the emirs/chiefs as glorified ‘collecting agents’. Non-Islamic colonial courts were introduced alongside Islamic sharia courts, gradually facilitating a non-Islamic judicial alternative for the populace. Secular schools were also set up against the traditional Qur’anic and Islamic schools, a move that long resisted, especially by the dominant tribes of the north. Other potent colonial ‘novelties’ that considerably weakened the northern traditional system were currency and health care systems: the ancient use of natural traditional legal tenders like cowrie shells were replaced with colonial coins and notes, while hospitalized health care replaced traditional herbal, ritual or spiritual medications.

Eventually, the northern socio-political and cultural landscape was modified by three of the most powerful colonial tools: the judiciary, education/schooling and currency. All rules and regulations governing the society were sanctioned by the judiciary; colonial missionary schools (most resisted then) targeted not just the social psyche but also religious beliefs/tenets; currency, then as now, pervades all commercial/trade transactions,from buying farms/houses to buying vegetables or fish for the day’s family soup.

Compared to the over 1,000 years of Arabic and Islamic presence in the north(including the Kanem empire), colonial ‘novelties’ in language (English), education,judiciary, religion (Christianity) and government could muster only about 100 years of presence (Davies, 1956). It is not surprising, therefore, that the dominant part of the northern population has been resistant, in variable degrees, to Western/European culture,be it in the form of education or polity.

From the 1950s to date, colonial legacies like formal secular education, democracy,and other Western nuances of human rights have made considerable inroads into precolonial northern traditions and culture. However, the average northern Nigerian has,since 1960, been fraught with pent-up or sub-conscious resistance to or suspicion/resentment of colonial/Western culture, deeply perceived by the average non-educated(possibly Muslim) northerner asalienandcrafty/tricky. This average social belief has been further strengthened by years of post-colonial public misrule and mismanagement by both civilian and military elites, whom the average non-educated northerner views as crafty/tricky and disappointing (as aptly captured in Hausa namings likeyan boko[Westernized ones];dogon turanci[gibberish English];kwance tushe[legacy destroyer—the constitution]). This third example, a Hausanized phonological imitation of the word ‘constitution’, borders on the suspicious view of the adopted colonial/Western (democratic)constitution as replacing long held customs and traditions.

The seeds of the current Boko Haram insurgency were planted long before the largely attributed 2003 Kanamma/Taliban revolt in Yobe State; long before the disappointed calls for Sharia rule in the north at the beginning of the current Fourth Republic. Indeed, the seeds started germinating in the said colonial era of Nigeria. They sprouted and started growing after Nigerian independence, watered by a series of post-colonial misrules and mismanagements, all of which were associatively summed up by the average uneducated northerner in one word:boko(Western culture’).

Thus, when the Boko Haram insurgency erupted in 2009, many an average noneducated (Muslim) northerner identified it with his/her pent-up resentment/suspicion ofbokoand were initially largely sympathetic to the insurgency. In that sympathy,mixed with some awe, even the residents of Maiduguri had initially regarded the battle as exclusive to only two opposing sides: the insurgents and the government. Later on, when the insurgents included ‘fellow Muslims’ (whether culpable or innocent) among their targets, a deep and wide socio-cultural ‘quake’ occurred, not just in the north-east but across the entire northern part of Nigeria. Since the insurgency assumed a nihilistic dimension across northern Nigeria from 2012 to date, certain changes have occurred in the region’s socio-cultural, political, and religious psyche—from its religious perceptions,attitudes, and practices, to its social cohesions and political orientations, the north has considerably changed.

This study intends to use the socio-semiotic tool (Halliday, 1978, 2007; Van Leeuwen,2005; Gursimsek, 2014) to briefly examine some of those changes. The tool will be used to analyze both the Boko Haram [henceforth, BH] terrorist strategies as multimodalpromptsand the socio-semiotic changes of the north as multimodalresponsesto theprompts.

The Social Semiotic Framework

The social semiotic theoretical framework is first a product of general semiotics, in both its structural and social perspectives (Saussure, [1916] 1985; Peirce, 1985), and specifically an extension of Halliday’s (1978) functionalist view oflanguage: ideational,interpersonal and textual (Halliday, 2007). Social semiotics identifies verbal language as only one of the various semiotic modes, signs, or resources that facilitate social cohesion,communication and interaction (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001). Such a socio-semiotic view of language accords communicative values to all modes (linguistic or non-linguistic)of stimulus and response that indicate interactive signs like interest, attitude, gestures,emotions, and so on. Accordingly, for instance, this theory could regard animageof fire as communicatively more significant, semiotically more relevant, among anon-Englishspeakingvillage community, than theEnglish word‘fire’.

Thus, social semiotics considers not only the mode and structure of a semiotic sign but also how such a sign influences and guides social behaviour; how interpersonal and social relations are defined or re-defined by the use of such signs (Bucy, 2004; Jensen,1998; Kress, 2010). In this regard, social semiotics subsumes aspects of pragmatics and sociolinguistics, whereby the communicative function of language includes negotiation and control of interpersonal behaviour.

Code and Sign

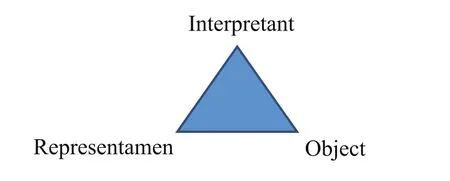

The terms ‘code’ and ‘sign’ tend to occur interchangeably in some semiotic studies (Eco,1976; Chandler, 2002). They both denote somedeliberatecomposition or use of certainresourcestocommunicatesome idea or message. However, whereas ‘code’ denotes somesystematic useor composition of any resource of communication, ‘sign’ meansbothacodeas well as its possibleinterpretations.A simplistic explanation of the unity of sign is the one given in the triadic process (Eco, 1976), modelled after Ogden and Richard’s (1923)diagram:

This process above shows that a unified sign process involves a sign vehicle (Representamen)used to express a referent (Object) and an extra sense made (Interpretant) by linking theRepresentamento itsObject. Many semioticians, however, posit that the semiotic sign process is more dynamic and extensive than this (Kress, 2010; Van Leeuwen, 2005). In many instances, a sign may be interpreted in simultaneously multiple ways or forms. Each of these interpretations can be taken as an additional/new sign. In turn, each new sign could trigger other new signs, in what is termedinfinite semiosis. For instance, theimageof aflowermay be variably interpreted as the word ‘flower’, as garden, as love, as a new life, or any of a number of others. In turn, a new interpretive sign likelovecould further convey another new one, along a different perspective, like ‘my wife’ or ‘my Ann/Halima’to a man, relative to his romantic experience.

Mode and Multimodality

The termmodecan be simply defined as theformal aspectof the means/resource used to make or convey some meaning. Such a mode can be classified into two broad types:(i) verbal/linguistic, and (ii) non-verbal/non-linguistic (Kress, 2010). The verbal formal aspect subsumes spoken and written language, while the non-verbal one covers images/photo/pictures/videos (visual), gestures/facial expressions/postures/movements (practical), non-linguistic sounds (aural/acoustic), and so on.

A semiotic sign or resource can consist ofone mode or more: when they comprisemore than onemode, they are known as multimodal. For instance, a terrorist video clip can be seen as a multimodal semiotic resource, comprising speeches and writings/print (verbal mode), gestures and movements (practical) and other various features of the video itself (visual, aural, etc). Multimodality is a semiotic theoretical perspective that facilitates an organized analysis or study of all modes of semiotically significant resources assembled in any given sign. Multimodality not only accounts for themodalvariety of semiotic resources within a given sign, but also facilitates parallel descriptions of simultaneous or sequential operations of those resources. For instance, a terrorist video clip may contain a ‘terrifying semiotic sign’ coded in the simultaneousverbalthreat of murder and thefiringof a machine gun by the same person (usingverbal,practical, andvisualmodes].

Interpretants and Affordances

As explained in the triadic process above, aninterpretantis aresponsiveproduct of a prior sign (Eco, 1976). An interpretant may reveal some obvious relation between it and itsprompt(the sign that triggers it), as in the relation betweensmokeandfire(indexical) or apictureof an object and theactualobject (iconic). The relation between some interpretants and their prompts may not be so obvious (Gursimsek, 2014), as infear(interpretant) and the sight of asnake(in which case, the intermediate interpretant,danger, has to occur in order to establish the next one,snake). Asignlikesnakecould thus have more than onepossible interpretant, depending on the socio-semiotic situation and its participants. The sign ‘snake’(verbal/non-verbal) could therefore be variably, or even simultaneously, interpreted asdanger,poison,beauty, etc. Indeed, to a professional snake charmer, that snake sign may even be interpreted asfriendorwealth! Such an extensive semiotic potential of a sign is known as itsaffordance(Van Leeuwen, 2005). Hence, affordance and interpretant can both be seen as interpretive products of prior signs; however, affordance proffers a more comprehensive dimension of interpreting a sign.

In socio-semiotic studies, even practical, behavioural, or attitudinal instances in particular situations can be analysed as affordances of prior signs. For instance, a practicalsign(prompt) like a terrorist suicide bomb explosion at a market could triggeraffordanceslikefear,closureof shops,arrival/presence of security agents,subsequent public avoidance of all other market places in that town, and so on. Conversely, all these affordances can constitutenew signsoffearordanger.

Data Analysis and Discussion

The data to be analysed are classified into two main types: (i) verbal semiotic resources(inscriptions in visual clips, terrorist utterances, etc), and (ii) non-verbal semiotic resources (images, videos, audios, etc). The dominant and most potent modes of the Boko Haram (henceforth, BH) terrorist campaign are non-verbal, such as the use of knives and firearms, killings, and releases of propaganda photos/video clips. The analysis of such multimodal ensembles (Bezemer & Jewitt, 2010) will also entail highlights of their social impacts within a socio-semiotic framework.

The Good-Bad Ensemble

Almost all terrorists using the banner of Islam have one of their salient socio-semiotic attacks at their ‘host communities’ in ensembles ofthe goodwiththe bad. That is, they tend to combine certainIslamicnames/terms/expressions withterroristacts or utterances.The Islamic framing of terrorist acts or intents serves as both anattractive strategyas well as adefensive mechanism. They also use such conflicting resources in single signs to createideological confusionin extremely terrified minds (as captured byinterrogative affordancesbelow). For instance, in a typical BH photo or video clip, a terrorist may be simultaneouslyslaughteringa (Muslim) person and shoutingAllahu Akbar(‘God is Great!’). By associative semiosis, the society targeted by such a clip could discern some or all of the following affordances:

Allahu Akbar→ BH is Islamic, Allah-fearing.

{slaughter} → Killing a human being is bad/repulsive/terrifying.

Allahu Akbar+ {slaughter} → The killing is Islamic.

→ Is the killing Islamic?

→ BH is thus Islamic.

→ The killing is not Islamic.

→ BH is thus not Islamic.

→ Islamic or not, the killing is terrifying.

→ BH is terrifying.

Such a framing or codifying technique has enabled the BH to (a) attract many Muslim youths into its mission, and (b) cow the ‘host community’ into awe and silence. Even though the northern community has subsequently reacted against the BH campaign in the region, only a minor, more easily observable aspect of that reaction materialized in local vigilante captures and killings of suspected BH members. The major aspect of that reaction includes the resurgence of Islamic preachings, especially on the religious alienation of BH and in support of inter-religious tolerance; Islamic attitudes and utterances even at non-religious functions like political rallies/presentations, social engagements, simple domestic chats/conversations; greater religious re-awakening among both northern Muslims and Christians; increased militancy among the youth;militarization of public security policing. Unlike some 20 years ago, today, the northern political elite (both Muslim and Christian) has made religious citations a salient sociosemiotic tool for public addresses, political campaigns and persuasion. All these changes have been triggered by such BH campaigns as analysed above.

Another instance of practicalgood-badsemiotic ensemble used by the BH for such defensive/legitimizing purposes but which has eventually drastically affected the (Muslim)social perspective is the use ofveiledyoungfemale Muslimsto carry outsuicide bombings(see images below).

This socio-semiotic resource/sign conveys the following affordances:

{the veil} → Islamic, feminine, vulnerable, honourable

{the female} → Islamically, females are protected, not feared/persecuted.

{the veiled female} → an honourable womanhood in Islam

{the bombing} → bad, fatal, terrifying, wicked, evil

{the veiled female bombing} → The bombing is bad, fatal and terrifying.

→ The bomber is veiled.

→ The bomber is a female.

→ The bomber is a Muslim.

→ Veiled persons are suicide bombers.

→ Veiled females are suicide bombers.

→ Veiled female Muslims are suicide bombers.

→ Veiled female Muslims are dangerous.

→ Veiled female Muslim bombers are BH members.

→ BH is Muslim, dangerous and terrifying.

Such associative affordances above have drastically altered the larger society’s view and attitude towards veiled women in public places, especially anywhere at which such bombings have (repeatedly) occurred. Muslims still know theIslamic valueof theveil,but their human instinct for survival has largely introduced some element ofsuspicionorfearinto their previousadmiration(religious and romantic) of such veilings. Being compassionate and protective to females (Muslim or non-Muslim), which is a cardinal Prophetic virtue (sunnah) in Islam, has greatly been compromised by such agood-badsocio-semiotic ensemble.

The Faceless Face Resource

Compared to the sizes of their ‘host communities’, terrorist groups have a much smaller population. For instance, if the BH insurgents were to be approximately totalled at 30,000, they would constitute only about 0.02% of the Nigerian population (at 160 million). However, using one salient socio-semiotic resource, they have managed to make theirpresencefelteverywherein Nigeria and byeveryonein Nigeria. That resource is thefaceless face. Often, it is not the deadliness of terrorist guns or bombs that instils fear into the society; it is the attacker’s lack of obvious distinctive identity. In such a situation, anyunknownface or object becomesknownas asuspect. The unpredictability of BH attacks has weakened a long-cherished culture ofhospitalitytostrangers, as guests or passers-by,in northern Nigeria. In that vein, consider the following signs and affordances:

PRE-BH PERIOD:

{a stranger} → guest, blessing, deserving hospitality

POST-BH PERIOD:

{a stranger} → strange, suspicious: dangerous?

In Hausa, the most widely spoken language in northern Nigeria, there are two proverbs, both framed around the codebа?о(‘strange/stranger’), which best highlight the conceptual shift in hospitality among the Hausa and, by extension, northern Nigerians:

PRE-BH PERIOD:

bа?опkа annabinka

‘guest-your prophet-your’

(Your guest [is] your prophet.)

POST-BH PERIOD:

bа?иwаrfuska.

‘strange face’

(a strange face)

Before the BH insurgency, an unknown visitor or a passer-by used to be treated as aguest; following the eruption of the BH insurgency, such a visitor/passer-by is treated asstrangefirst, until his subsequent attitude/actions ‘qualify’ him/her to the status ofguest.Both proverbs are framed around the wordbа?о(‘strange/stranger/guest’). The second part of the first ensemble above introduces apositivereligious metaphor (‘your prophet’),and thereby automatically limits thepossibleinterpretation ofbа?оto ‘guest’. The second part of the second ensemble introduces themost salienticonic resource ofidentity(‘face’), and thereby limitsbа?оto ‘strange’, chosen from three denotations ofbа?о.Such proverbs serve as socio-conceptual banners among many African ethnic groups,prominent among whom are the Hausa. Hence, both in verbal citation and social practice after the emergence of BH terrorism across northern Nigeria, the proverbbа?иwаr fиskаhas had greater socio-semiotic significance thanbа?опkа аппаbiпkа. This is also true of other socio-semiotic shifts in resources likenakiya(‘cake/grenade’?);almajiran malam

(‘disciples/terrorists’?);bи?а??iуаr wаsi?а(‘open letter/open terrorist threat’?).

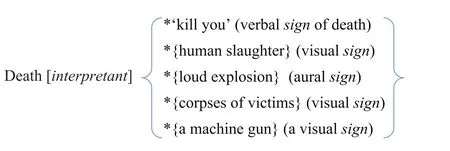

Multimodality of Death and Fear

The ultimate offensive socio-semiotic weapon of all terrorists is not a knife or firearm; it isdeath, the main effect of which isfear, whether individual or social. However, thesignsofdeathandfearare encoded in variousmodesby the terrorists and by their individual/social audience, respectively. The term multimodality, as mentioned above, is generally applied by semioticians to semiotic ensembles that individually comprise more than one type of mode. For instance, a video clip can be seen as a multimodal sign in terms of its images (visual mode), voices (aural/verbal mode), background print/inscriptions(typographical/verbal mode), and so on. In a more extensive view ofinfinite semiosis;however, the communicative chain of semiotics may start with asign, then move to itsinterpretant, which, in turn, can be anew signfor anotherinterpretant, and on and on.Accordingly, asignlike thesoundof a gunshot can be interpreted as thedeathof a victim;thatinterpretantofdeathcan be construed as asignofsorrowfor the victim’s family, and so on.

Terrorist groups like BH tend toreverseor re-assign the concept ofmultimodalitytoonesalientinterpretant(notsign) ofnumerous signs:

The repeated use of all suchsignsultimately leads to only one socially salientinterpretant:death. This remains an affordance ofonesalientinterpretantofvarious sign modes. In this sense, themultimodalityapplies more toseparate signsbearingone interpretant, rather than toone signcomprisingvarious modes. In response to thisinterpretive promptofdeath, the targeted society may show the nextresponsive interpretantoffear. Such aninterpretanttoo can be realized from different semioticmodes. Thesemodesoffearconstitute almost all the social changes triggered by BH terrorism:

In northern Nigeria today, especially the north-eastern part, a number of changes can be seen: security policing has become highly militarized; religious preachings/sermons have become socially less inflammatory; social festivities/events have become either low-key or moreIslamized; official/political addresses or speeches have become moreIslamized; roads and highways have become punctuated with more security check points and displaced beggars. All thesesignscan convey one salientinterpretant:fear.Conversely,fearcan also be construed as asignof theseinterpretants. This is what I see as acircular/infinite semiosis of terrorist multimodal codifications. So, on a higher sociosemiotic plane,deathandfearconstitute twoconversesalient points ofterrorist semiotics:

SIGN INTERPRETANT

Death → Fear

Fear → Death

Multimodality of a Boko Haram Clip

A photo or video clip is a multimodal mega sign. Every such clip is thus a semiotic ensemble of numerous sub-signs, possibly belonging to various linguistic and visual semiotic modes. Images, whether still or moving, are essential tools of advertisement or information dissemination for individuals, agencies, groups and institutions. Terrorist groups like BH deliberately or instinctively compose certain semiotic modes into one mega sign in the form of a photo or video clip and release the clip to a society in order to instil fear and their ideology into that society.

A socio-semiotic analysis of such a clip has to take the iconography (visual feature)and iconology (visual ideology) (Panofsky, 1955; Liu, 2013) of the clip into consideration.Such images can thus be socio-semiotically interpreted at three levels of iconicity: (i) preiconographic level: denotative meaning; (ii) iconographic level: connotative/associative meaning; (iii) iconological level: ideological meaning. The most significant sociosemiotic levels are the second and third. The first level, however, is still essential as a point of departure known by both the sign encoder and its interpreter. For instance, using an image of a ‘gun’ to indicate ‘danger’ or ‘death’ to someone who has never seen or known the use of guns will deprive that image of even itspre-iconographicfunction.

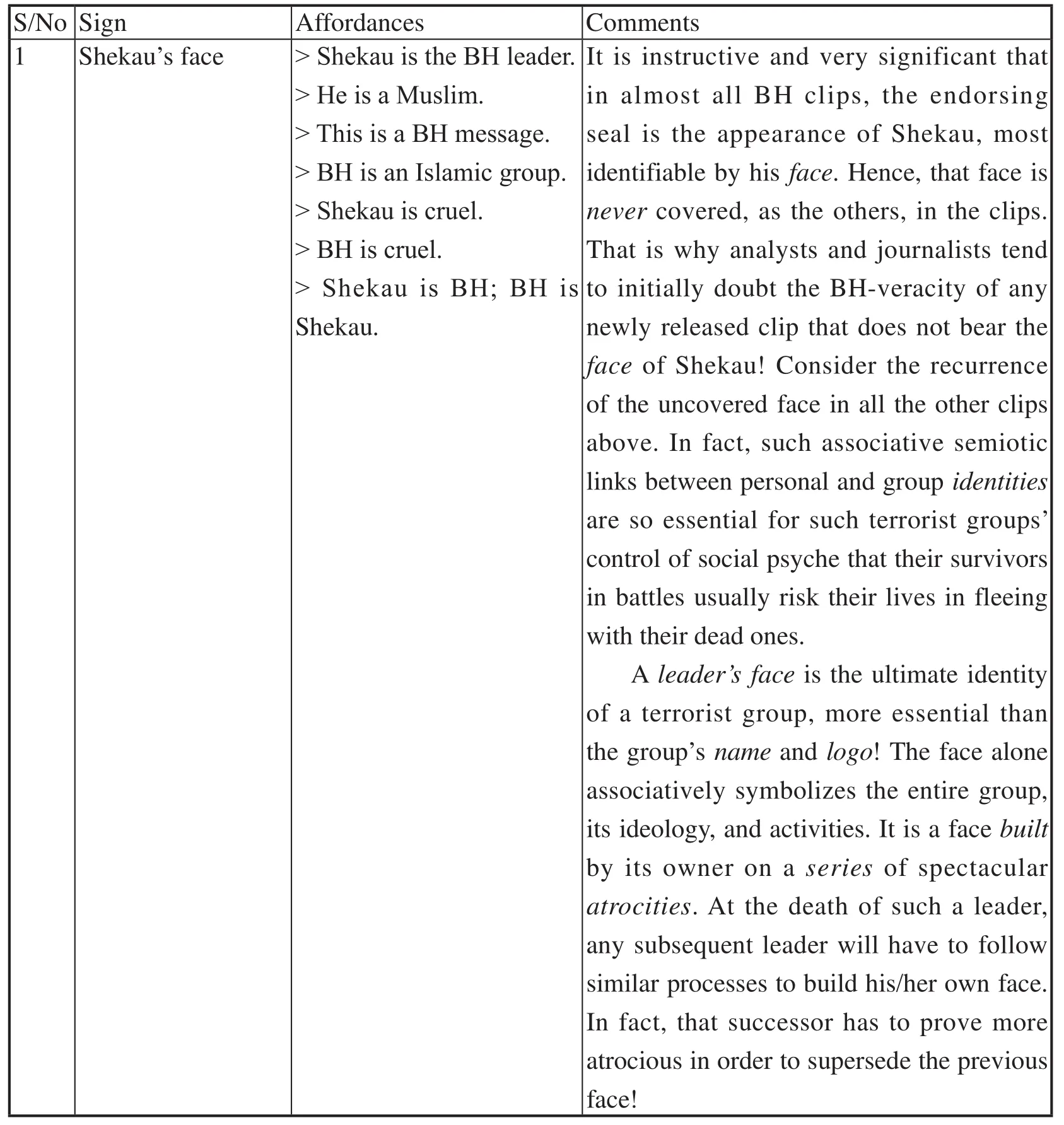

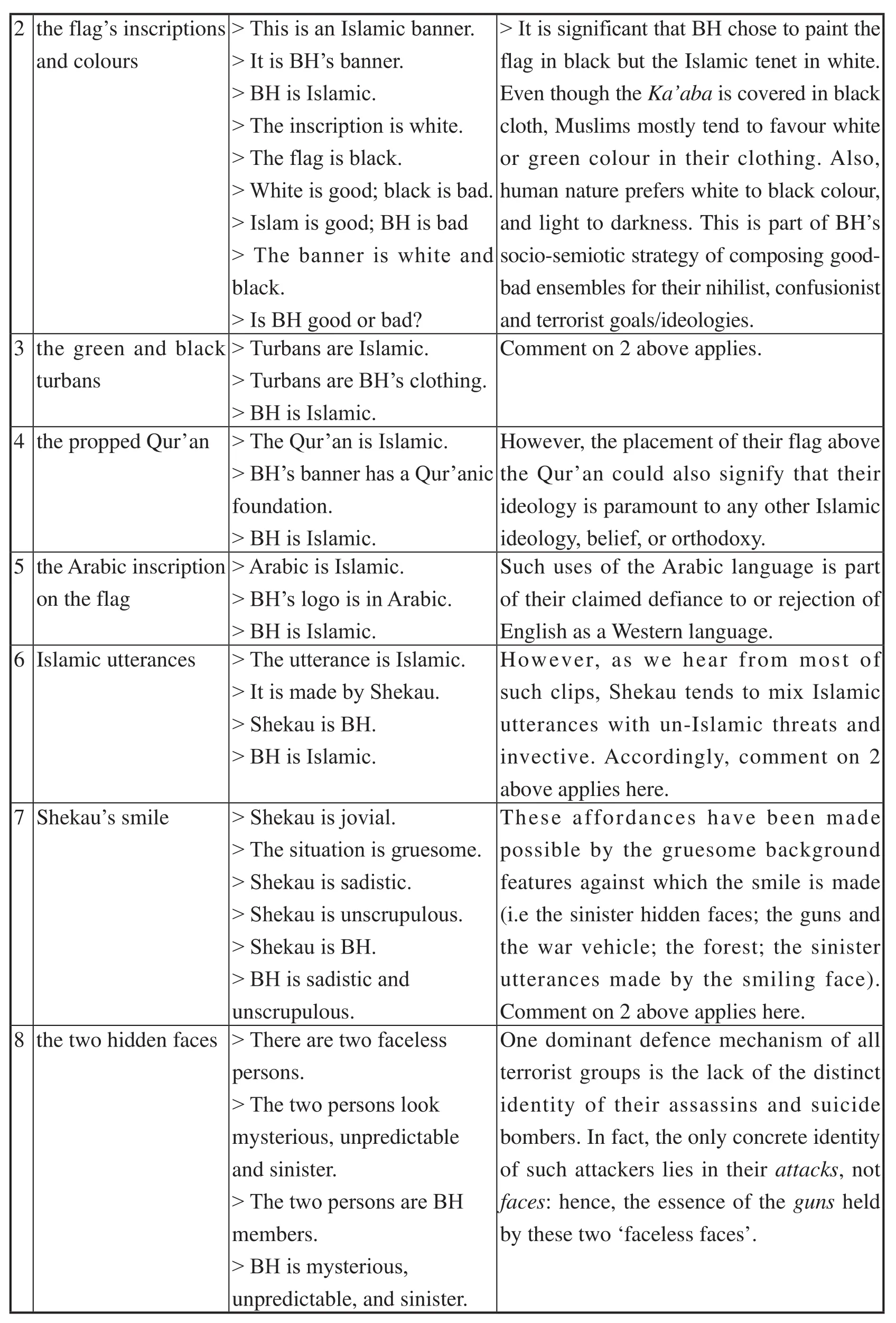

Through the images below, we will examine the multimodality of a typical BH photo/video clip and its affordances.

SHEKAU 1

SHEKAU 2

SHEKAU 3

SHEKAU 4

SHEKAU 5

SHEKAU 6

SHEKAU 7

In the images above, SHEKAU 1 (the first image) shows the BH leader, Shekau,flanked by two of his lieutenants, smiling and holding some papers. All the three of them are wearing camouflage Nigerian army uniforms and are turbaned; however, while the faces of the two lieutenants are hidden by the turbans, Shekau’s face remains uncovered and smiling. All the three are bearing AK47 machine guns, with the green-turbaned lieutenant holding his gun, while Shekau’s gun and the other lieutenant’s are slung over their shoulders. Shekau and that lieutenant are wearing black turbans. Behind the trio is an armoured vehicle, painted too in Nigerian army camouflage colours. Further behind the vehicle is part of a forest. In the top left angle/corner of the clip, is a black flag, bearing the white Arabic inscription of the first tenet of Islam and placed above a propped Holy Qur’an.

The salient semiotic resources in this clip are: Shekau’s face; the two hidden faces; the guns; the armoured vehicle; the turbans; the flag; the Qur’an; the forest background. The dominant ensembles are:

1)Islamic ensembles:

Verbal/Linguistic: the flag inscriptions; the Qur’an inscriptions; any Islamic utterances made by Shekau

Iconographic: the flag; the Qur’anic image; Shekau’s face; the papers

Iconological: same asiconographicabove

2)Terrorist ensembles:

Verbal/Linguistic: any terrorist utterances made by Shekau

Iconographic: Shekau’s face; the two hidden faces; the guns; the armoured vehicle;the forest; the black flag; the black turbans; Shekau’s smile against the gruesome background (weapons, hidden ‘terrorist’ faces, the forest, etc)

Iconological: same asiconographicabove

A detailed socio-semiotic analysis of these ensembles above is presented in a tabular way as follows:

?

?

?

Conclusion

The study shows that terrorist groups can emerge and thrive only if they are historical and socio-cultural parts of their target society, a fact that enables the terrorists to easily blend in with that society. Although firearms like guns and bombs appear to be the major tools of destruction for BH, their most potent weapons have been identified as socio-semiotic.In a country with a total population of 160 million like Nigeria, the firearms of BH have been said to have annihilated approximately 20,000 lives. Meanwhile, their sociosemiotic weapons have variably ‘hit’all160 million people of Nigeria, most critically affected of whom are the millions in the north, and especially the north-east. In fact, even this approximation of 20,000 fatalities constitutes a central element of BH’s ideological warfare or campaign against society. For everyonelife killed by a BH gun, a released image or even the sound of their gun alone can psychologically affectthousandsof people who must have seen or learned of that lone gun-killing. BH usesdeath(of a victim) as asemiotic sign, a weapon of instillingfearinto a society, individually and collectively. Thatfearenables BH to easily control social concepts, perception, and behaviour.

Any consistent/persistent and prolonged terrorist campaign against a society increases the degree and depth of social control for terrorist groups like BH. Hence, the longer the campaign lasts, and the wider an area it covers, the greater its ability to control and change society becomes. The seven-year old BH terrorist campaign across northern Nigeria,especially its north-eastern part, has made an impact on various aspects of the people’s lives in variable degrees. From religious perceptions and attitudes, to interpersonal and social interactions, to trade and travel, the landmarks of BH-related changes are evident.In some respects, individuals and communities in northern Nigeria may return to their pre-BH mental and material states; in many more others, however, the northern society may have changed for a long time to come.

Ahmed, U., & Daura, B. (1976).Classical Hausa and major dialects. Zaria: Northern Nigeria Publishing Company.

Bezemer, J., & Jewitt, C. (2010). Multimodal analysis: Key issues. In L. Litosseliti (Ed),Research methods in linguistics(pp. 180-197). London: Continuum.

Bucy, E. P. (2004). Interactivity in society: Locating an elusive concept.The Information Society:An International Journal,20(5), 373-383.

Bulakarima, S. U., Sheriff, B., & Abba, S. B. (2003).Kanuri-English dictionary. Maiduguri:Desktop Cooperative Society.

Chandler, D. (2002).Semiotics: The basics. London: Routledge.

Davies, J. G. (1956).The Biu book. Zaria: Norla.

Dudley, B. J. (1968).Parties and politics in northern Nigeria. London: Frank Cass.

Eco, U. (1976).A theory of semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ellis, S. (2002). Writing histories of contemporary Africa.Journal of African History,43, 1-26.

Gursimsek, R. A. (2014). Designing visual worlds: Multimodality and co-creation of meaningful places in multi-user virtual environments.Journal of Art and Design,2(2), 1-23.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978).Language as social semiotics: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2007).Language and society. London: Continuum.

Jagger, P. J. (2001).Hausa. Amsterdams: Benjamins.

Jensen, J. F. (1998). Interactivity: Tracing a new concept in media and communication studies.Nordicom Review,19(1), 185-204.

Kress, G. (2010).Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication.London: Routledge.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001).Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Edward Arnold.

Liu, J. (2013). Visual images interpretive strategies in multimodal texts.Journal of Language Teaching and Research,4(6), 1259-1263.

Meek, C. K. (1931).Tribal studies in northern Nigeria. London: Kegan Paul.

Newman, P., & Newman, R. M. (1979).Modern Hausa-English dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ogden, C. K., & Richards, I. A. (1923).The meaning of meaning. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Panofsky, E. (1955).Meaning in the visual arts. New York: Doubleday.

Peirce, C. S. (1985). Logic as semiotic: The theory of signs. In R. E. Innis (Ed),Semiotics: An introductory anthology(pp. 4-23). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Saussure, F. de. ([1916] 1985).Course in General Linguistics. London: Duckworth.

Suberu, R. T. (2001).Federalism and ethnic conflict in Nigeria. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Trimingham, W. S. (1962).The influence of Islam upon Africa. London: Longmans.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2005).Introducing social semiotics. New York: Routledge.

(Copy editing: Curtis Harrison)

About the author

Ahmed Umar (ahmed.umar@fud.edu.ng), an Associate Professor of English and General Linguistics, has been a multilingual person since his adolescence. His command of five languages (English, Arabic, Hausa, Bura and Kanuri) enabled him to combine English Language and General Linguistics in his studies for Bachelors, Masters, and Doctoral degrees. Similarly, all his academic research and publications (www/ahmedumar/linguistics) have entailed comparisons of two or more of the five languages he knows. His publications include 3 books published in Europe and many articles, spanning phonology,morphology, syntax, semantics, stylistics, pedagogy, and literature. He has been a university lecturer for 18 years in the University of Maiduguri and Federal University Dutse, and taught over 20 courses in various areas of specialization.

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Wilhelm II’s ‘Hun Speech’ and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I

- The Meaning and Madness of Money: A Semio-Ecological Analysis

- Facebook Engagement and Its Relation to Visuals,With a Focus on Brand Culture

- Contemporary Discriminatory Linguistic Expressions Against the Female Gender in the Igbo Language

- Stasis Salience and the Enthymemic Thesis1

- A Century in Retrospect: Several Theoretical Problems of Russian Formalism From a Paradigm Perspective