Wilhelm II’s ‘Hun Speech’ and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I

Andreas Musolff

University of East Anglia, UK

Wilhelm II’s ‘Hun Speech’ and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I

Andreas Musolff

University of East Anglia, UK

Kaiser Wilhelm II’s speech to a German contingent of the Western expedition corps to quell the so-called ‘Boxer Rebellion’ in 1900 and develop the imperialist drive for colonies further, is today remembered chiefly as an example of his penchant for sabre-rattling rhetoric. The Kaiser’s appeal to his soldiers to behave towards Chinese like the ‘Huns under Attila’ was,according to some accounts, the source for the stigmatizing labelHun(s)for Germans in British and US war propaganda in WWI and WWII, which has survived in popular memory to this day. However, there are hardly any reliable data for such a link and evidence of the use of ‘Hun’ as a term of insult in European Orientalist discourse. On this basis, we argue that a ‘model’ function of Wilhelm’s speech for the post-1914 uses highly improbable and that,instead, theHun-stigma was re-contextualised and re-semiotized in WWI. For the duration of the war it became a multi-modal symbol of allegedly ‘typical’ German war brutality. It was only later, reflective comments on this post-1914 usage that picked up on theapparentlink of the anti-GermanHun-stigma to Wilhelm’s anti-ChineseHunspeech and gradually became a folk-etymological ‘explanation’ for the dysphemistic lexeme. The paper thus exposes how the re-semiotized termHunwas retrospectively interpreted in a popular etymological narrative that reflects changing connotations of political semantics.

colonialism, dysphemism, folk-etymology, resemiotization, stigma, World War I

1. Introduction

To this day, the nickname “Hun” for a German individual or for a group of Germans counts in present-day Britain as a dysphemistic, offensive insult that dates back to World War I and has by now become sufficiently obsolete to be used mostly tongue in cheek,often with reference to football. In the run-up to the 2014 Football World Championship,for instance, John Grace in theGuardianweekend magazine gave a review of past performances of the England team, in which the 1990 semi-final match against West Germany was characterized as an event “in which the beastly Hun went ahead from a deflected free kick” (The Guardianmagazine, 31 May 2014). In 2011, aDaily Mailcommentator confessed: “My late grandmother was German, which makes me enough of a Hun to represent Germany at sport, ...” (Daily Mail, 22 July 2011), and during the 2010 World Championship, which took place in Germany, theDaily Starran the title, “Ze Hun are big on fun!” (The Guardian: Greenslade Blog, 25 June 2010). The termHunalso features as a citation (and often as a good punning opportunity) in articles that discuss anti-German stances and relate them to lingering resentments from World Wars I and II;e.g. in headlines such as, “Stop making fun of the Hun” (The Observer,28 November 2004); “We’re far too horrid to the Hun” (New Statesman, 21 June 1996). The last time that a British press organ used the name in (quasi-)earnest appears to have been in 1994 when theSunboasted of having prevented the participation of the modern German army in the 50th anniversary commemorations of the end of World War II (intended as a symbol of post-war reconciliation) that were planned for the following year: “The Sun bans the Hun.The Sun’s proud army of old soldiers and heroes last night forced John Major to ban German troops from marching through London” (The Sun, 24 March 1994).

But what have Germans got to do with the “Huns” in the first place? Dictionaries agree on the basic definition ofHun/Hunsas referring to an ancient Asian people who,in the words of theOxford English Dictionary,“invaded Europe c. AD 357, and in the middle of the 5th c., under their famous king Attila [c. 406-453 CE] overran and ravaged a great part of this continent” (OED, 1989, Vol. VII, p. 489; compare alsoBrewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable,1999, p. 596;Encarta World English Dictionary,1999,p. 918).1In view of the fact that modern Germans trace themselves back culturally,linguistically and sometimes, ethnically, to the ancient “Germanic” peoples as they appear in ancient Roman historical literature since the days of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) and that their representatives in the 4th and 5th centuries CE were on the receiving end of theHunattack, there appears to be no genealogical link that might motivate an identification of either ancient or modern Germans as “Huns”. However, since the early 19th century,Huncould also be used in British English in a pejorative, negatively orientalist (Said,2003) sense as a general designation for any kind of “reckless or wilful destroyer of the beauties of nature or art: an uncultured devastator” (OED, 1989, Vol. VII, p. 489). Its use as a stigmatizing term for a war enemy is not in itself surprising, but why was it directed at the Germans and why did it emerge in World War I? In the following sections we shall chart the outline of this dramatic change in its political-historical indexicality and, as we will see with reference to multi-modal representations of theGerman-as-Hun, also its iconicity, which led to the emergence of an enduring national symbol.2On this basis we argue that the term underwent a “re-semiotization” that turned it from a vague historical analogy into a national stigma, which has since acquired a discourse-historical index, complete with a folk-etymological, empirically unsubstantiated narrative about its alleged origins.

2. How the Huns Got a Bad Name From the Germans

2.1 The Kaiser’s speech

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of WWI, the British newspaper,TheDaily Telegraph, gave several explanations for the origin of theHunepithet for Germans. One of its articles focused on the war crimes committed by German armies in their initial attack on Belgium, which had “[helped] persuade millions that Germany had descended from being a nation of high culture to one capable of barbarism akin to Attila the Hun” (The Daily Telegraph,2014a). In anotherTelegrapharticle, the same editor, B. Waterfield, pointed out that in a “notorious speech” from 14 years before, Emperor Wilhelm II had “bidden farewell to German soldiers sailing to China to put down the Boxer Uprising—and urged them to be ruthless, and to take no prisoners”, just as the “Huns had made a name for themselves a thousand years before”. Waterfield also mentioned Rudyard Kipling’s poem “For All We Have and Are”, published on 2 September 1914, which begins with the verse, “For all we have and are; For all our children’s fate; Stand up and meet the war. The Hun is at the gate!” (Kipling, 1994, pp. 341-342). TheTelegraphjournalist credits the poem with having made the epithetHun“stick” (The Daily Telegraph,2014b).

As retold by Waterfield and in several popular and scholarly dictionary accounts (Ayto,2006, p. 43;Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable,1999, p. 596; Green, 1996, p. 308;Forsyth, 2011, p. 78; Hughes, 2006, pp. 243-244;OED, 1989, Vol. 7, p. 489), the earliest use of the Huns-Germans analogy has been identified in the German Emperor Wilhelm II’s farewell address to a contingent of troops embarking in Bremerhaven to join the ‘Western’Powers’ invasion of China to quell the so-called “Boxer rebellion”, which was delivered on 27 July 1900. Deviating from the prepared text as he liked to do, the Kaiser exhorted the soldiers to behave ‘like the Huns’ in order to win historic glory. To the dismay of his Foreign Secretary, Bernhard von Bülow, who tried to impose a ban on the spontaneous version, it was published first by a local newspaper on 29 July (Bülow, 1930-31, pp.359-360; MacDonogh, 2000, pp. 244-245) and the next day, byThe Timesin a slightly shortened but overall faithful English translation (quoted afterOED,1989, Vol. 7, p. 489):“No quarter will be given, no prisoners will be taken; Let all who fall into your hands be at your mercy. Just as the Huns a thousand years ago under the leadership of Etzel [=ancient German name of ‘Attila the Hun’] gained a reputation in virtue of which they still live in historical tradition, so may the name of Germany become known in such a manner in China that no Chinaman will ever dare to look askance at a German.”3

In Germany and abroad, the Emperor’s bellicose appeal triggered strong reactions,which varied, predictably, depending on political attitudes towards the Empire’s colonial projects but were largely seen as part of a long series of diplomatic gaffes (Clark, 2012, p.235; Geppert, 2007, pp. 159-167; R?hl, 1988, p. 21; Stürmer, 1994, pp. 338-340). Within imperial Germany, the discrepancy between the official text and its actual delivery as reported by theWeser-Zeitungled to attempts by the government (and by sympathisers of Imperial German rule to this day, see e.g. www.deutsche-schutzgebiete.de, 2017) to pretend—against witnesses’ evidence—that the Kaiser’s speech had not been belligerent and had not in fact contained the above-quoted passage, or only in a much ‘softer’ form(Behnen, 1977, pp. 244-247; Klein, 2013; Matthes, 1976; S?semann, 1976).

Despite such apologetics, Wilhelm’s grotesque comparison came to haunt his government when, in the autumn of 1900, even the censored German press started reporting about atrocities against the Chinese population, which were based on German soldiers’ letters and testimonies. Some of the letters were cited by opposition leaders in theReichstagparliament and, in an obvious allusion to Wilhelm’s ‘Hun speech’, were nicknamed ‘Hun letters’ (Hunnenbriefe) by the Social Democrats’ press (Vorw?rts,1900a, b). In his official response, the War Minister, H. von Go?ler, issued a blunt denial; however, even he conceded that “His Majesty’s speech might have been open to misunderstandings”, not least through establishing the reference to the “Huns” (Ladendorf 1906, 124, for the context of theReichstagdebate see Wielandt, 2007; Wünsche, 2008).

On the other hand, for Germany’s expansionist imperialists, the Kaiser’ speech would have chimed perfectly with their “Self”-stereotypes of a nation that needed not only to catch up with other European Powers in the “race” for colonies but had a mission to surpass and even take over the role of chief-coloniser and -civiliser on other continents(Rash, 2012). To them as to himself, Wilhelm II’sGermans-Huns-analogy would have made sense as an appeal to the German soldiers’ courage, not as an order to commit atrocities. After all, in their and their Kaiser’s view, China was a “heathen culture” that had “broken down” because “it was not built on Christianity” (Klein, 2013, p. 164). In a previous speech to another army contingent embarking in Wilhelmshaven, Wilhelm II had even stated that the German troops (together with the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, British,American, French, Italian and Japanese contingents of the “Eight Nation Alliance”) were fighting for “civilization” and the “higher” good of the Christian religion (Behnen, 1977, p. 245; for the German colonialist ambitions in China see also Fleming, 1997; Hufer,2003; Leutner & Mühlhahn, 2007). It would have been utterly paradoxical for Wilhelm to ask his soldiers to behave “barbarically” because such an appeal would have run against the whole line of his colonialist argumentation, which tried to legitimize imperialist aggression as an enterprise to “civilize” allegedly backward, “barbaric” nations (Klein, 2006). Even those members of the German Imperial elite who cringed at theGermans-as-Hunscomparison, such as Foreign Secretary, Bernhard von Bülow, who was to become Imperial Chancellor a few months after the Bremerhaven speech, agreed with the Kaiser that Germany should take its rightful place “under the sun” and join other world powers in the race for colonies (Bülow, 1977, p. 166).

Wilhelm’s positive reference to the “Huns” was also in line with their popular image in 19th century Germany as a famous ancient, warlike Asiatic people who had challenged the Roman Empire and were remembered for their braveness and ferocity (see, e.g.Brockhaus, 1838, Vol. 2, p. 427; compare also the (anachronistic) depiction of the Hun leader in Eugene Delacroix’ painting, see appendix 1). Wilhelm’s use of the literary nameEtzelfor the Hun leader,Attila, further underlines the fact that he was not engaged in a scientifically based comparison in his Bremerhaven speech. The nameEtzeloriginates from the 13th century Middle High German epic poem, theNibelungenlied,in which the‘Hunnish’ king of that name is the blameless but also helpless victim of his murderous in-laws, theNibelungs,who kill his wife and his son and lay his castle in ruins in their ultimately self-destructive rage (Hardt, 2009). Given his bystander-role in the poem,Wilhelm II’s choice of him as the model of military leader thus seems to be based on as little detailed knowledge of the literary figure as of the historical personality of Attila.Rather, we may assume, the Kaiser alluded, on the basis of very superficial knowledge,metonymically to the stereotype of a famous warrior-king, in order to exhort ‘his’ soldiers to establish a reputation of Germany as a warrior-nation.

2.2 World War I

Fourteen years after the Kaiser’s speech, his Empire, together with its Austro-Hungarian ally was at war with four of its erstwhile allies from the Chinese campaign, Britain,France, Russia and Japan. Two further, America and Italy would join them later. Barely one month into the war, Britain’s popular colonial and war poet, Rudyard Kipling,published the following poem:

For all we have and are,

For all our children’s fate,

Stand up and meet the war.

The Hun is at the gate![Highlighted by AM]

Our world has passed away

In wantonness o’erthrown.

There is nothing left to-day

But steel and fire and stone.

Though all we knew depart,

The old commandments stand:

“In courage keep your heart,

In strength lift up your hand.”

Once more we hear the word

That sickened earth of old:

“No law except the sword

Unsheathed and uncontrolled,”

Once more it knits mankind,

Once more the nations go

To meet and break and bind

A crazed and driven foe.

Comfort, content, delight—

The ages’ slow-bought gain—

They shrivelled in a night,

Only ourselves remain

To face the naked days

In silent fortitude,

Through perils and dismays

Renewed and re-renewed.

Though all we made depart,

The old commandments stand:

“In patience keep your heart,

In strength lift up your hand.”

No easy hopes or lies

Shall bring us to our goal,

But iron sacrifice

Of body, will, and soul

There is but one task for all—

For each one life to give.

Who stands if freedom fall?

Who dies if England live?

(The Times, 2 September 1914, quoted after Kipling, 1994, 341-342)

By the time the poem was published, Britain had sent an “Expeditionary Force” to Belgium and France to help them counter the German attack which threatened to overrun Belgium and to conquer Paris. Britain’s official reason to enter the war was the safeguarding of Belgium’s internationally recognized neutrality but there was also a complex of further strategic interests (defense of the British Empire’s preeminence as a global power and of Britain’s homeland; prevention of German hegemony; intensification of the “entente” with France and Russia) that made a military confrontation with Germany seem inevitable (Clark, 2012; Karlin, 2007; Matin, 1999). In his poem, Kipling takes an unambiguously patriotic stance, portraying the enemy as a “crazed and driven foe” that started the war and has already brought it to Britain’s “gate”. Britain/England has no choice to defend herself but is also part of a coalition of “all mankind” that fights for their own and their children’s “freedom” and “for all we have and are”, i.e. a better world than that in which only the “sword” ruled, “unsheathed and uncontrolled”. TheHun-Germans bring back that “old” world of barbarity, brutality and lawlessness which in the orientalist discourse of the 18-19th centuries had been reserved as a characterization of non-European nations (Said, 2003).

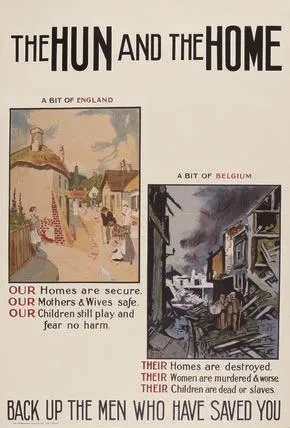

Compared with Wilhelm II’s one-dimensionalHun-Germananalogy based on an (assumed)terium comparationisof military prowess, its anti-German version in Kipling’s 1902 and 1914 poems, anda fortiorithose of the Allied war propaganda 1914-1918, painted a much more colorful picture of barbaric brutality and depravity, as illustrated also by British and US American war posters during the following years. In these posters—for a small selection, see appendices 2-4—theHun-German featured as the absolute Other of (Western) culture, i.e. as a destroyer of homes and families, a rapist and murderer with blood-stained hands, with further accessories such as the “Pickelhaube” helmet, blood-dripping sword or bayonet, a plump, burly figure and a grimacing face and even as a “King Kong”-like ape monster, wielding “Kultur” as a club, ready to commit more atrocities. These multimodal, text- and picture-combining depictions appeal to the onlooker to do everything in his or her power to stop “the Hun” in his tracks, i.e. to join the Allied armies or to support them by buying war bonds. Besides texts and pictorial depictions, theHun-stereotype also featured in films, such asThe Hun Within, The Kaiser,the Beast of BerlinandThe Claws of the Hun,all from 1918 (Taylor, 2003, p. 186;H?lbling, 2007; Leab, 2007).

Since the start of the war, Allied propaganda had amassed a bulk of more or less factual evidence of German war crimes, especially in occupied Belgium, which documented reports of civilian and prisoner executions, occasional rapes and the destruction of cities and cultural monuments (Bryce, 1915; Wilson, 1979; Messinger,1992, pp. 70-84; Zuckermann, 2004). Allied media reports exaggerated these “atrocity news” to the point of inventing “fake news” of mass rapes, impaling of babies and the erection of “corpse factories”, perpetrated by the barbarian enemy (Cull, Culbert & Welch, 2001, p. 25; Neander & Marlin, 2010; Schneider & Wagener, 2007; Taylor, 2003,pp. 178-180). All contributed to the stereotype of Germans as Huns who were worse than the original invaders under Attila: TheBirmingham Post(31 August 1914), for instance,attested “infamy greater than the fiery Hun” to the Germans, and theDaily Express(13 January 1915) deemed any comparison to Wilhelm an “Insult to Attila” (Schramm, 2007, p. 420). What had been a vaguely alluded to analogy with an ancient warlord in his 1900 speech had been turned into a self-fulfilling stereotype that needed no historical predecessors. By the end of the war, the stigmatization of Germans asHunshad become firmly entrenched in the British national and imperial public as well as in the US public(as part of the propagandistic effort to prepare America’s entry into the war). Government appeals, print media, posters and films depicted the GermanHunas a destroyer of homes and families, a rapist and murderer with blood-stained hands, surrounded by ruins and raped or murdered women and children (Sanders & Taylor, 1982; Schramm, 2007, pp.415-420; Taylor, 2003, pp. 178-180, 186; Thacker, 2014, pp. 48, 63, 162-163). TheHunstereotype even engendered a family of derivations that exclusively referred to the WWI-context and had nothing to do with the ancient Huns, e.g.Hundom, Hunland, hunless,Hun-folk, Hun-hater, Hun-talk; Hun-eating, Hun-hunting, Hun-pinching, Hun-raiding,Hun-sticker(‘bayonet’) (cf. OED, 1989, Vol. 7, p. 489; Dickson, 2013, p. 70). The latter coinages went out of fashion soon after the war, but their temporary popularity during WWI show that the erstwhile grounding of theHun-epithet for Germans in an analogy with Attila’s Huns had largely disappeared. Its post-1914 users did not need anything to know about ancient Huns to interpretHunas a stigma term for Germans. Both the historical-cultural indexicality of the termHunand its iconicity had radically changed:from referring to the half-legendary ancient invaders of Europe and the Roman Empire to 20th century Germany as the World War I-enemy that had almost destroyed Western civilization and culture.

2.3 A ‘missing link’?

Clearly, to say that the British/Allied WWI-sterotype ofGermansas Hunswas different from or even opposed to the vague comparison hinted at by the Kaiser in 1900 would be a gross understatement. His boast about German troops’ military prowess equaling that of the ancient Huns was a hyperbolic simile at best. The national and international public’s embarrassed and sarcastic reactions quickly led to ironical deconstruction and critical reinterpretation (see theHun-letters). By contrast, theGermans-as-Hunsstereotype of WWI became a relatively stable “meme” (Dawkins, 1976), which survived for long after the War and only started to fade semantically towards the end of the 20th century. Nowadays, as we have seen above (part 1), it serves as a historical reference that can be employed ironically to invoke the memory of WW1-like resentments against Germany without endorsing them.

Whilst the continuity between the post-1914 Hun-German stereotype and its later versions can be described fairly straightforwardly in terms of a ‘historicization’ process,in which a once-popular term becomes obsolete and starts to index a specific historical context, the proposed model function of Wilhelm II’s speech for the emergence of the stereotype (see above, part 2.1) remains unproven and is in our view dubious. In the first place, there is a huge contrast in the connoted evaluation: Wilhelm II intended hisEtzel-/Hun-allusion as a positive appeal to his soldiers, encouraging them to fight bravely whereas Kipling’s and all other Allied voices’ usage was characterized by the utmost derision and condemnation ofGerman-as-Hunnishbehavior. Secondly, there are no documented contemporary (WWI) uses among the latter that quote or refer to the Kaiser’s speech, even not asprima facieevidence of his endorsement ofHunnishbehavior. Given the degree of hatred for the Kaiser in the Allied camp, this would have been a missed opportunity: after all, his speech could have been quoted as proof of his liking forHunnish“barbarism”. Instead, theHun-as-Germanstereotype was re-invented and invested with a new iconicity that made it into a substantially new semiotic structure.

Thirdly, existing philological evidence shows that the post-1914 stereotype had pre-1900 sources, which themselves had got nothing to do with the Kaiser’s speech. As a derogatory epithet, the termHunhad in fact been available during nineteenth century English usage, together withGothandVandal, for designating “an uncultured devastator” or anyone “of brutal conduct or character” (OED, 1989, p. 489; Green, 1996, p. 307; Radford & Smith, 1989, p. 264). As early as during the Franco-German war of 1870-71,The Standard(9 November 1870) had criticised the siege of Paris as leading to “deeds that would have shamed the Huns” (Hawes, 2014, p. 130). This usage clearly prefigures the WWI uses quoted above. Interestingly, there are also German texts on record which used the Hun-epithet against “barbaric” war-crimes, allegedly committed by British forces in the Second Boer-war (1899-1902). Its title is “Huns in South Africa: Comments on British politics and war-conduct” (Hunnen in Südafrika. Betrachtungen über englische Politik und Kriegsführung, Vallentin, 1902). And at the start of WWI, German newspapers reporting on the Russian invasion of East Prussia on Germany’s Eastern Front, denounced Russian soldiers asHunnishwar criminals (Schramm, 2007, p. 420).

These examples show thatHun-comparisons were used in both German and English public discourse to suggest an inferior, barbaric and degenerate status of their referents vis-à-vis the more highly valued national/cultural Self, regardless of whether the latter was a British, German, European or Western “imagined community” (Anderson, 2006). Viewed against this background, Wilhelm II’sGermans-as-Hunsanalogy to praise and inspire his own soldiers was the odd one out. Rudyard Kipling’s usage in 1914, on the other hand, does fall into line with the mainstream usage—and so does an earlier poem,The Rowers,from 1902, in which he had warned against the British Empire leaguing“With the Goth and the Shameless Hun”,as occasioned by a German proposal that Britain should help in a threatening show of naval power against Venezuela (Kipling, 1994, pp.341-342).

Overall, we can conclude that it is most probably this mainstream pejorative meaning ofHun, which is attested throughout the 19th century, rather than Wilhelm II’s idiosyncratic boastful Bremerhaven usage, that provided the basis for the British and US post-1914 stigmatization ofGermans as Huns. Kipling’s powerful 1914 poem may have made the stigma-label “stick” as Waterfield says (The Daily Telegraph,2014b), but he did not need to invent it.

3. Conclusions

From a semiotic viewpoint, we can interpret the history of the termHunin twentieth century English as a case of a fundamental “re-semiotization”, in the sense in which this term is used in multilingualism and intercultural communication research (Blommaert,2005; Scollon & Scollon, 2005). The original function ofHunas a “nation-name” that was borrowed from Asian languages is preserved in the reference to the migrating peoples that entered Europe in late Antiquity and came into contact with the Roman Empire and various European tribes of the Migration Period. Through popular Euro-centric memory culture, the vague reference to military confrontations with the armies of Attila, the orientalist meme of theHuns under Attilawas preserved in several West European speech communities; in nineteenth century English it had become a floating signifier, together withVandalsandGoths, to designate and stigmatize any group suspected of “barbarity”, lack of “civilization” and ignorance of/resistance to Western “cultural” standards. As such it was used, as we have seen, by the British and German media before World War I, not just against extra-European nations but also as a condemnatory label to criticize brutal warfare of European Powers (Franco-German War, Boer War). Wilhelm II’s idiosyncratic reference to Attila and the Huns in the context of the colonialist Western war on China during the so-called “Boxer rebellion” was most probably a less than fully intentional allusion to this orientalist stereotype, which confused the historical war leader with a literary figure and linked them improbably with the courage of German soldiers of the day. The Kaiser’s usage was (deservedly) a source of embarrassment to his government and an object of derision for the press and parliamentary opposition even within Imperial Germany; hence, its popular impact was minimal.

When at the outbreak of World War I, the mainstreamHunnickname and stigma was firmly attached to Germany through British voices such as R. Kipling’s and a host of media and propaganda outlets, including pictorial and filmic realizations, the first main re-semiotization took place. Instead of the vague historical reference to an ancient“barbaric” invader from outside Europe, its reference was narrowed down to (Imperial) Germany as a war-enemy that was worse in brutality, barbarism and cruelty than any other contemporary or previous war-faring nation (including the “Huns under Attila”). It was turned into a multimodal symbol of extreme “Otherness” that had to be resisted and vanquished at all cost. The depiction of theHunas aKing Kong-like monster in one of the War propaganda posters (see appendix item 3) is an apt rendition of this stigmatized stereotype. ThePickelhaube-helmeted GermanHun-ape is the unpalatable, extreme Other of any human civilised Self – be it individual or collective. Unlike the Kaiser’s usage,the re-semiotizedHun-stigma had strong socio-historical impact: it has been linked to the harsh treatment of defeated Germany in the Versailles Peace treaty (1919), which had to be “sold” to the public in the Allied public as a “just” punishment of an unambiguously evil enemy, and the mistrust and cynicism in the British and US public following the post-WWI revelations about the exaggerations and misrepresentations of Allied propaganda, which later led to disbelieving attitudes concerning early atrocity reports from Nazi Germany (Taylor, 2003, pp. 195-197).

During the Second World War and the confirmation of Holocaust news, of course,the WWI-stigma, which was still in living memory, could be revived again and served another round of condemnatory national stereotyping (examples in OED, 1989, Vol. VII,p. 489). Soon after, however, especially with West Germany being (re-)admitted to the“Western Civilization” side of the “Cold War”, the ideological and polemical power of the stereotype declined sharply. It was “historicized” in the sense of being indexed as a quaint reminiscence of WW1/2 discourse that—as we saw from the introductory examples—is still remembered but no longer emphatically endorsed or combatted. At most, it signals an ironical distance to a once fiery hatred against the enemy, which can nowadays safely be referenced in the context of football competition and can be “ornamented” with folk-etymologies citing the grotesque rhetorical efforts of the last German monarch.Its historical indexicality is still sufficiently strong to prevent it from becoming again a floating signifier, and the demise of Western Orientalism and ethnocentric essentialism will hopefully prevent it from becoming a “floating stigma” as well.

Notes

1 Similarly for the German cognateHunne, cf. Brockhaus, 1954, Vol. 5, pp. 583-584; Duden,2014, p. 395; Kluge, 1995, p. 388. Ultimately, these and other Indo-European cognates ofHunmay be traced back to a Chinese loanword; cf. De la Cruz-Cabanillas, 2008, p. 257.

2 The termsicon,indexandsymbolare used here in the sense of Peirce’s classic typology (Peirce,1994, 1998).

3 The original German text can be found in Klein, 2013, p. 164.

Ayto, J. (2006).Movers and shakers: A chronology of words that shaped our age.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Behnen, M. (Ed.). (1977).Quellen zur deutschen Au?enpolitik im Zeitalter des Imperialismus 1890-1911.Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Blommaert, J. (2005).Discourse: A critical introduction.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brockhaus. (1838).Der Volks-Brockhaus. Deutsches Sach- und Sprachw?rterbuch für Schule und Haus(9th ed.). Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

Brockhaus. (1954).Der gro?e Brockhaus. Wiesbaden: F. A. Brockhaus.

Bryce, V. J. (1915).Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages. London: HMSO.

Bülow, B. F. von. (1930-1931).Denkwürdigkeiten(Ed., F. von Stockhammern) (Vols. 1-4). Berlin:Ullstein.

Bülow, B. F. von. (1977). Erkl?rung im Reichstag zu Grundfragen der Au?enpolitik (Stenographische Berichte über die Verhandlungen des deutschen Reichstages, 4. Sitzg. 1897, 60-62). In M.Behnen (Ed.),Quellen zur deutschen Au?enpolitik im Zeitalter des Imperialismus 1890-1911(pp. 165-166). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Clark, C. (2012).The sleepwalkers: How Europe went to war in 1914. London: Allen Lane.

Cull, N. J., Culbert, D. H., & Welch, D. (2001).Propaganda and mass persuasion. A historical encyclopedia 1500 to the present.Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio.

Dawkins, R. (1976).The selfish gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De la Cruz-Cabanillas, I. (2008). Chinese loanwords in the OED.Studia Anglica Poznaniensa, 44,253-274.

deutsche-schutzgebiete.de. (2017). Der Boxeraufstand 1900/1901. Hunnenrede. Was sagte Kaiser Wilhelm II. wirklich? Retrieved from http://www.deutsche-schutzgebiete.de/hunnenrede.htm

Deutsches Historisches Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.dhm.de/lemo/objekte/pict/pl003967/index.html

Dickson, P. (2013).War slang: American fighting words & phrases since the Civil War. Mineola,NY: Dover Publications.

Duden.(2014).Das Herkunftsw?rterbuch. Etymologie der deutschen Sprache(Ed., J. Riecke).Berlin: Dudenverlag.

Fleming, P. (1997).Die Belagerung zu Peking. Zur Geschichte des Boxer-Aufstandes.Frankfurt:Eichborn

Forsyth, M. (2011).The etymologicon: A circular stroll through the hidden connections of the English language. London: Icon Books.

Geppert, G. (2007).Pressekriege. ?ffentlichkeit und Diplomatie in den deutsch-britischen Beziehungen (1896-1912). Munich: Oldenbourg.

Green, J. (1996).Words apart. The language of prejudice.London: Kyle Cathie.

Hardt, M. (2009). Attila – Atli – Etzel. über den Wandel der Erinnerung an einen Hunnenk?nig im europ?ischen Mittelalter.Behemoth. A Journal on Civilisation,2, 19-28.

Hawes, J. (2014).Englanders and Huns: The culture clash which led to the First World War.London: Simon & Schuster.

H?lbling, W. H. (2007). The long shadow of the Hun. Continuing German stereotypes in U.S.literature and film. In T. F. Schneider & T. F. Wagener (Eds),“Huns” vs. “Corned beef”:Representations of the other in American and German literature and film on World War I(pp.203-214). G?ttingen: V&R unipress.

Hufer, H. (2003).Deutsche Kolonialpolitik in der ?ra des Wilhelminismus: Asien und der Boxeraufstand. Munich: GRIN-Verlag.

Hughes, G. (2006).An encyclopedia of swearing: The social history of oaths, profanity, foul language, and ethnic slurs in the English-speaking world. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Iedema, R. (2003). Multimodality, resemiotisation: Extending the analysis of discourse as multisemiotic practice.Visual Communication,2(1), 29-57.

Karlin, D. (2007). From Dark Defile to Gethsemane: Rudyard Kipling’s war poetry. In T. Kendall(Ed.),The Oxford handbook of British and Irish war poetry(pp. 51-69). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kipling, R. (1994).The works of Rudyard Kipling. Ware: Wordsworth.

Klein, T. (2006). Strafexpedition im Namen der Zivilisation. Der ?Boxerkrieg? in China (1900–1901). In T. Klein & F. Schumacher (Eds.),Kolonialkriege. Milit?rische Gewalt im Zeichen des Imperialismus(pp. 145-181). Hamburg: Hamburger Edition.

Klein, T. (2013). Die Hunnenrede (1900). In J. Zimmerer (Ed.),Kein Platz an der Sonne: Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte(pp. 164-176). Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Kluge. Etymologisches W?rterbuch der deutschen Sprache.(1995). Bearbeitet von E. Seebold.Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Ladendorf, O. (1906).Historisches Schlagw?rterbuch.Stra?burg: Trübner.

Leab, D. J. (2007). Total war on-screen: The Hun in U.S. films 1914-1920. In T. F. Schneider &H.Wagener (Eds.),“Huns” vs. “Corned beef”: Representations of the other in American and German literature and film on World War I(pp. 153-185). G?ttingen: V&R unipress.

Leutner, M., & Mühlhahn, K. (Eds.). (2007).Kolonialkrieg in China. Die Niederschlagung derBoxerbewegung 1900-1901. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag.

MacDonogh, G. (2000).The last Kaiser. William the impetuous. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Matin, A. M. (1999). ‘The Hun is at the gate!’: Historicizing Kipling’s militaristic rhetoric, from the imperial periphery to the national center—Part 2, The French, Russian and German threats to Great Britain.Studies in the Novel,31(3-4), 432-470.

Matthes, A. (Ed.). (1976).Reden Kaiser Wilhelms II.Munich: Rogner & Bernhard.

Messinger, G. S. (1992).British propaganda and the state in the First World War.Manchester:Manchester University Press.

National Army Museum. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://prints.national-army-museum.ac.uk/image/443663/david-wilson-the-hun-and-the-home-1918-c

Neander, J., & Marlin, R. (2010). Media and propaganda: The Northcliffe Press and the Corpse Factory Story of World War I.Global Media Journal—Canadian Edition,3(2), 67-82.

Peirce, C. S. (1994).Peirce on signs: Writings on semiotic(Ed., J. Hoopes). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

Peirce, C. S. (1998).The essential Peirce. Selected philosophical writings(Vols 1-2) (Eds., N.Houser & C. Kloesel, Peirce Edition Project). Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Radford, E., & Smith, A. (1989).To coin a phrase. A dictionary of origins(New edition). London:Papermac.

Rash, F. (2012).German images of the Self and the Other. Nationalist, colonialist and anti-semitic discourse, 1871-1918. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Room, A. (Ed.). (1999).Brewer’s dictionary of phrase and fable. London: Cassell.

Rooney, K. (Ed.). (1999).Encarta world English dictionary. London: Bloomsbury.

R?hl, J. C. G. (1988).Kaiser, Hof und Staat: Wilhelm II. und die deutsche Politik.Munich: Beck.

Said, E. W. (2003).Orientalism.London: Penguin.

Sanders, M. L., & Taylor, P. M. (1982).British propaganda during the First World War, 1914–18.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schneider, T. F., & Wagener, H. (Eds.). (2007).“Huns” vs. “Corned beef”: Representations of the other in American and German literature and film on World War I. G?ttingen: V&R unipress.

Schramm, M. (2007).Das Deutschlandbild in der britischen Presse 1912-1919.Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2005). Lighting the stove. Why habitus isn’t enough for critical discourse analysis. In R. Wodak & P. Chilton (Eds.),A new agenda in (critical) discourse analysis. Theory, methodology and interdisciplinarity(pp. 101-111). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Simpson, J. A., & Weiner, E. S. C. (Eds.). (1989).OED, Oxford English dictionary on historical principles.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

S?semann, B. (1976). Die sog. Hunnenrede Kaiser Wilhelms II. Textkritische und interpretatorische Bemerkungen zur Ansprache des Kaisers in Bremerhaven vom 27. Juli 1900.Historische Zeitschrift, (222), 342-358.

Stürmer, M. (1994).Das ruhelose Reich. Deutschland 1866-1918.Berlin: Siedler.

Taylor, P. M. (2003).Munitions of the mind. A history of propaganda from the ancient world to thepresent day.Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Thacker, T. (2014).British culture and the First World War: Experience, representation and memory.London: Bloomsbury.

Vallentin, W. (1902).Hunnen in Südafrika. Betrachtungen über englische Politik und Kriegsführung.Berlin: E. Hofmann & Co.

Vorw?rts. (1900a). Hunnen-Greuel,Vorw?rts, 1. November 1900: 2.

Vorw?rts. (1900b). Hunnisches aus Ostasien,Vorw?rts, 15. November 1900: 1.

Wielandt, U. (2007). Die Reichstagsdebatten über den Boxerkrieg. In M. Leutner & K. Mühlhahn(Eds.),Kolonialkrieg in China. Die Niederschlagung der Boxerbewegung 1900-1901(pp.164-172). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag.

Wilson, T. (1979). Lord Bryce’s investigation into alleged German atrocities in Belgium, 1914-15.Journal of Contemporary History,14(3), 369-383.

World War 1 Propaganda Posters (n.d.). Retrieved from www.WW1propaganda.com

Wünsche, D. (2008).Feldpostbriefe aus China. Wahrnehmungs-und Deutungsmuster deutscher Soldaten zur Zeit des Boxeraufstandes 1900/1901.Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag.

Zuckerman, L. (2004).The rape of Belgium. The untold story of World War I.New York: New York University Press.

About the author

Andreas Musolff (a.musolff@uea.ac.uk) is Professor of Intercultural Communication at the University of East Anglia (Norwich, UK). His research interests include the Pragmatics of Intercultural communication, Metaphor Analysis, Public Discourse and Metarepresentation Theory. He has published the monographsPolitical Metaphor Analysis: Discourse and Scenarios(2016);Metaphor, Nation and the Holocaust(2010),Metaphor and Political Discourse(2004) and co-editedMetaphor and Intercultural Communication(2014). He is currently the Chairman of the International Association forResearching and Applying Metaphor(RaAM) and SeniorFellow and Marie Curie Fellow of the European Unionat the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS), University of Freiburg.

Appedices

Appendix 1. Attila, by Eugène Delacroix (1847)

Appendix 2 (Britain, 1918) ? National Army Museum(http://prints.national-armymuseum.ac.uk/image/443663/david-wilson-the-hun-and-the-home-1918-c)

Appendix 3. US War poster 1917(www.dhm.de/lemo/objekte/pict/pl003967/index.html)

Appendix 4. Beat back the Hun(US, 1918) (www.WW1propaganda.com)

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- The Meaning and Madness of Money: A Semio-Ecological Analysis

- Facebook Engagement and Its Relation to Visuals,With a Focus on Brand Culture

- Contemporary Discriminatory Linguistic Expressions Against the Female Gender in the Igbo Language

- A Socio-Semiotic Perspective on Boko Haram Terrorism in Northern Nigeria

- Stasis Salience and the Enthymemic Thesis1

- A Century in Retrospect: Several Theoretical Problems of Russian Formalism From a Paradigm Perspective