High prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis B and C in Minnesota Somalis contributes to rising hepatocellular carcinoma incidence

Essa A Mohamed, Nasra H Giama, Abubaker O Abdalla, Hassan M Shaleh, Abdul M Oseini, Hamdi A Ali,Fowsiyo Ahmed, Wesam Taha, Hager Ahmed Mohammed, Jessica Cvinar, Ibrahim A Waaeys, Hawa Ali,Loretta K Allotey, Abdiwahab O Ali, Safra A Mohamed, William S Harmsen, Eimad M Ahmmad, Numra A Bajwa, Mohamud D Afgarshe, Abdirashid M Shire, Joyce E Balls-Berry, Lewis R Roberts

Abstract BACKGROUND Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are known risk factors for liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). There is substantial global variation in HBV and HCV prevalence resulting in variations in cirrhosis and HCC. We previously reported high prevalence of HBV and HCV infections in Somali immigrants seen at an academic medical center in Minnesota.AIM To determine the prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis in Somali immigrants in Minnesota through a community-based screening program.METHODS We conducted a prospective community-based participatory research study in the Somali community in Minnesota in partnership with community advisory boards, community clinics and local mosques between November 2010 and December 2015 (data was analyzed in 2020). Serum was tested for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antibody, hepatitis B surface antibody and anti-HCV antibody.RESULTS Of 779 participants, 15.4% tested positive for chronic HBV infection, 50.2% for prior exposure to HBV and 7.6% for chronic HCV infection. Calculated age-adjusted frequencies in males and females for chronic HBV were 12.5% and 11.6%; for prior exposure to HBV were 44.8% and 41.3%;and for chronic HCV were 6.7% and 5.7%, respectively. Seven participants developed incident HCC during follow up.CONCLUSION Chronic HBV and HCV are major risk factors for liver disease and HCC among Somali immigrants, with prevalence of both infections substantially higher than in the general United States population. Community-based screening is essential for identifying and providing health education and linkage to care for diagnosed patients.

Key Words: Viral hepatitis; Liver disease; Community engagement; African; Immigrant health

lNTRODUCTlON

Globally, liver cancer ranks 6thin cancer incidence and 4thin cancer mortality[1]. For many years, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been the most common risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC) in the United States[2-6]. There is a high prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa[7-11]. Partly due to immigration from high-prevalence countries in Africa and Asia,hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains an important risk factor in the United States[12-15].Consequently, HCC disproportionately affects individuals of African and Asian ancestry and Hispanic ethnicity[16,17]. Africa has the youngest median [interquartile range (IQR); range] age at HCC diagnosis worldwide [45 (35-57; 8-95)], increasing the burden of years of life lost from chronic viral hepatitis.

Minnesota’s foreign-born population constitutes approximately 9% of the state population[18]. From 2008 to 2017, the Minnesota Department of Health reported an age-adjusted incidence rate of liver cancer of 22.4 per 100000 person-years among Black Minnesotans, a 4.3-fold higher rate than the rate of 5.2 per 100000 person-years among white, non-Hispanic Minnesotans[19]. A substantial proportion of Minnesota’s Black population are recent African immigrants[18,20-22]. However, due to a general lack of awareness of viral hepatitis, Minnesota’s most recent immigrants from Somalia have limited appreciation of their risk from chronic viral hepatitis and its associated complications[23].

To date, few studies have focused on chronic HBV and HCV infection and their sequelae among recent African immigrants to the United States. There is no population-based study of the rates of HBV and HCV infections among Somalis[20,24-28]. We previously conducted a clinic/hospital-based retrospective study of the rates of HBV and/or HCV infections in Somalis seen at Mayo Clinic from July 1996 to October 2009[29]. We found higher frequencies of chronic HBV (13.6%), prior exposure to HBV(55.5%), and chronic HCV (9.1%) in Somali Americans compared to 1.2%, 10.9%, and 2.2% respectively in non-Somali residents of Olmsted County (of whom 90% have European ancestry). Of 30 Somali HCC patients seen, 22 of 29 with available results (76%) were anti-HCV positive, while 5 of 28 with available results (18%) were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive. These results showed high rates of chronic HBV and HCV and revealed that HCV was a primary risk factor for HCC in Somalis[29]. Since clinic/hospital-based studies may overestimate true community disease prevalence, we tested for HBV and HCV in community-resident Somalis through a community-wide screening program.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional, community-wide screening study of Somali immigrant adults. Between November 2010 and December 2015, we used a community-based engagement research framework to offer free HBV and HCV screening to Somali immigrant adults living in Minnesota. Eligible individuals who self-identified as: (1) Of Somali descent; (2) ≥ 18 years of age; and (3) Resident in Minnesota received free HBV and HCV serological screening. Screening was provided for both foreign-born and United States-born participants. Study recruitment was carried out in the community. We partnered with three community-based health clinics with large Somali clienteles and faith-based establishments and charter schools, to which participants could come for enrollment and blood draws. In partnership with the Somali Health Advisory Committee (SHAC), a community advisory board based in Rochester and Minneapolis/St Paul, the research team provided educational seminars on viral hepatitis screening and liver disease. In addition, members of SHAC facilitated recruitment through word-of-mouth,advertisements, educational sessions and booths at various community events and health fairs in cities across Minnesota.

Study population

Individuals of Somali heritage who were at least 18 years of age were recruited to participate in the study. Participants provided written informed consent. At the completion of the study, participants received a $20 gift check (remuneration) mailed to their home address. Screening occurred at: (1) The Mayo Clinic Clinical Research and Trials Unit; (2) Community-based clinics; (3) A community-based health center; (4) Religious establishments (i.e. mosques); (5) Charter schools; or (6) At various community health-fairs. The study team consented and screened 779 participants aged 18 years to 91 years, of whom 49.9% (389) were male.

Ethical approval

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study and study related materials including flyers and weekly community outreach program documentation. Study team members conducted outreach field recruitment to inform potential participants about the study in both English and Somali.

Serological tests

Blood samples were processed, stored at -80 °C, and tested for HBsAg, hepatitis B core antibody(HBcAb), hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) and anti-HCV at the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology. Participants were administered surveys either in English or in Somali, assessing their age, sex, country of birth, cultural practices and immigration patterns. The screening results were organized into 5 groups depending on the serological test results (Table 1). The first 4 groups defined the hepatitis B infection status, while the fifth reported hepatitis C antibody status. The chronic HBV infected group was defined as those who tested HBsAg positive, HBsAbnegative, and HBcAb positive, regardless of anti-HCV status. The resolved HBV group, immune due to exposure to the live virus, was defined as participants who tested HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive and HBcAb positive, regardless of anti-HCV status. Combining the chronic HBV-infected group with the resolved HBV group gives the total number of persons exposed to live HBV infection. The vaccinated group was defined as those who tested HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive, and HBcAb negative,regardless of anti-HCV status. The HBV susceptible group was defined as those who tested HBsAg negative, HBsAb negative and HBcAb negative, regardless of anti-HCV status. Lastly, the chronic HCV infected group was defined as anyone who tested anti-HCV positive, regardless of HBsAg, HBcAb, or HBsAb status. We have previously shown that 93% of anti-HCV antibody-positive individuals in the Somali community also had measurable HCV RNA; thus, the rate of false positive anti-HCV antibody testing in this population is low[29]. Referrals for follow-up testing, health education, counseling,vaccination and treatment were provided to participants depending on their results.

Table 1 Antibody and antigen biomarkers for hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the study population. JMP (v.10; SAS Institute Inc.,Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses. Adjusted frequencies for viral hepatitis infection statuses were standardized using the 2010 United States Census and were stratified based on age and sex[30].

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

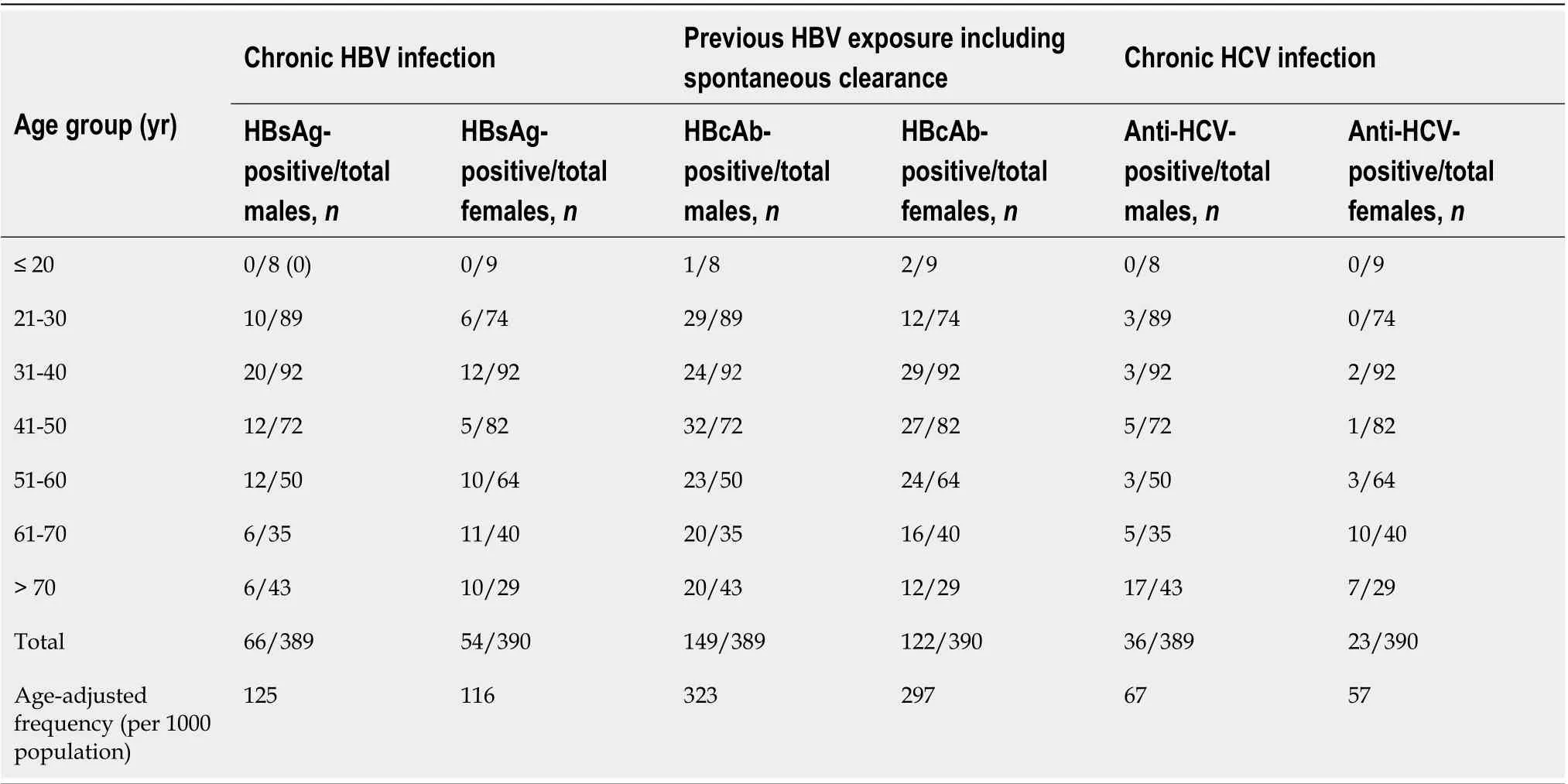

The study team consented and screened 779 participants aged 18 years to 91 years, of whom 49.9% (389)were male. This number represents 2.3% or 1 in 43 of the estimated 33208 Somalis aged 18 years to 84 years resident in Minnesota between 2013 and 2017[31]. The age distribution of the participants and the primary summary of rates are presented in Table 2.

Proportion of patients with HBV and HCV infections

The crude rates for each age and sex group are shown in Table 2, along with the age-adjusted rate for each group. Of the 779 Somali participants screened, 120 (15.4%) had chronic HBV (HBsAg+, HBcAb+,HBsAb-), and 271 (34.8%) were immune due to prior HBV infection (HBcAb+, HBsAg-, HBsAb+). In addition, a small subset of the patients had HBV and HCV co-infection (n= 5). The crude rates showed that, as is typical for HBV infection in Africa, many participants tested positive for chronic HBV infection by the age of 20. However, the converse was true for HCV, with most positive individuals being over 50 years. The age-adjusted rates for persons with chronic HBV were 12.5% and 11.6% for males and females, respectively. The age-adjusted rates for persons with resolved HBV, characteristic of prior exposure to HBV infection with spontaneous clearance, were 32.3% and 29.7% for males and females, respectively. For prior HBV exposure resulting in either chronic infection or spontaneous clearance, which measures all previous exposure to infectious HBV, the age-adjusted rates were 44.8%for males and 41.3% for females. Lastly, the age-adjusted positive rates for anti-HCV, the marker for HCV infection, were 6.7% for males and 5.7% for females. Of the 59 anti-HCV positive participants, 29(49.2%) had follow-up testing for HCV RNA, and 28 (96.6%) of the 29 tested positive. This was consistent with the results of our previous retrospective study, in which 93% of anti-HCV-positive Somalis were HCV RNA positive. The most common HCV genotype was 4 (43%) followed by genotype 3 (14%).

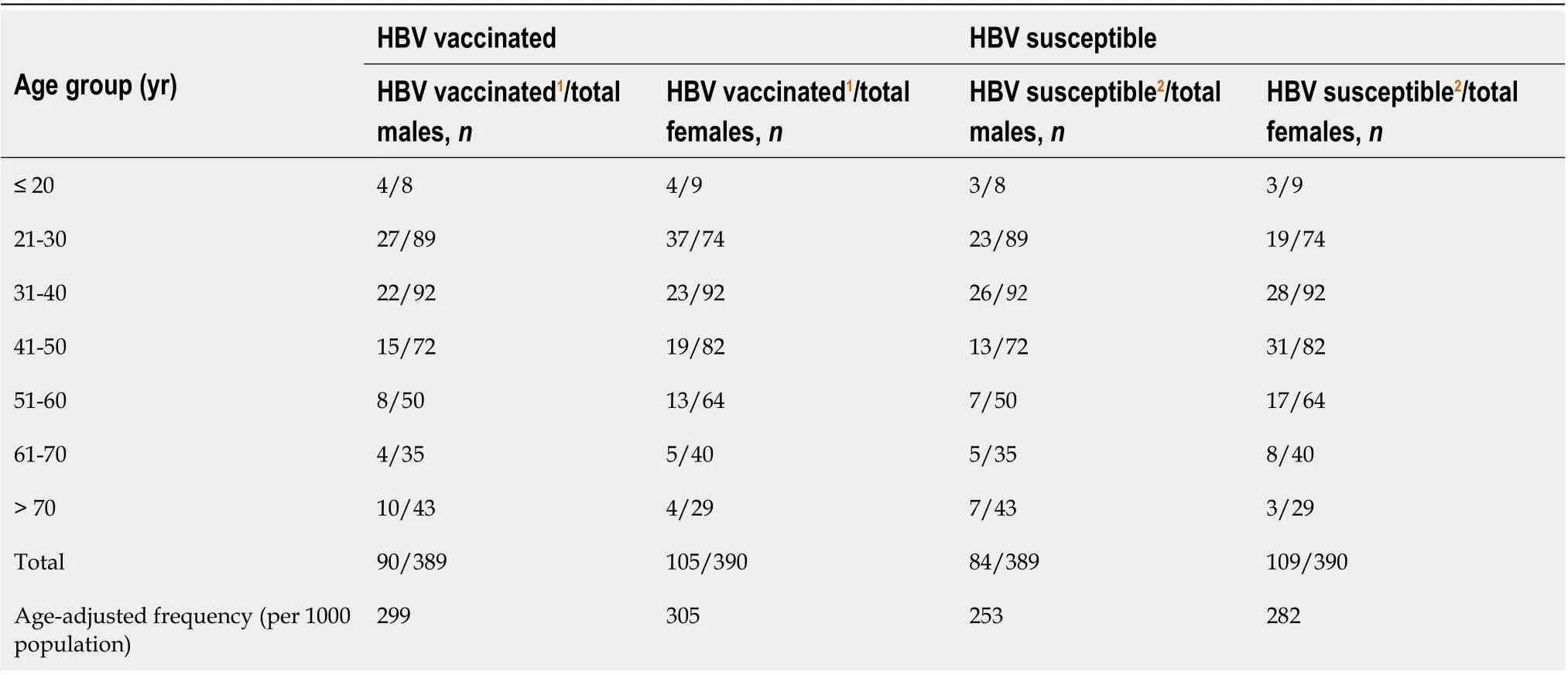

Proportion of patients vaccinated or susceptible to HBV infections

Of the 779 Somali participants, 388 (49.8%) had not previously been exposed to HBV. Of these, 195(25.0% of the total) tested positive for HBsAb only, consistent with immunity due to HBV vaccination.The remaining 193 (24.8%) tested negative for all HBV markers, indicating susceptibility to HBV(Table 3). Remarkably, of the 518 participants from this high prevalence community under age 50, 146(28.2%) were unvaccinated and susceptible to HBV.

Table 2 Frequency of hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-positive test results in Community Recruited Minnesota Somali Residents

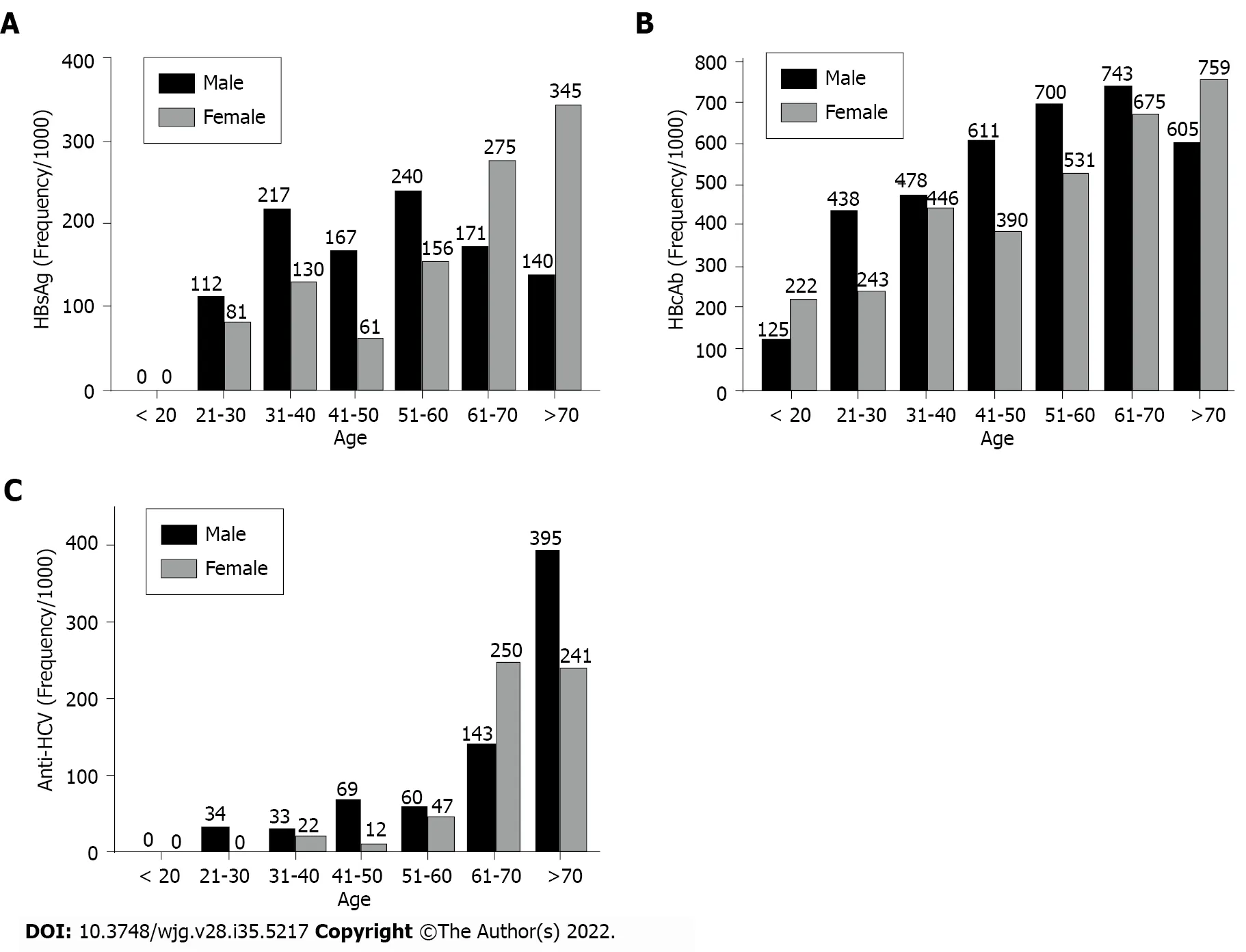

Age and sex group characteristics of HBV and HCV infections

Both age- and sex-specific rates showed differences. The highest proportion of HBsAg in Somalis was observed in females > 70 years of age (34.5%); in males, the highest proportion was in the 51-year-old to 60-year-old age group (24.0%) (Figure 1A). For HBcAb, the highest proportion of positivity for males was in the 61- year-old to 70-year-old age group (57.1%) and for females in the > 70-year-old group(41.4%) (Figure 1B). For anti-HCV, the highest proportion for males was > 70 years of age (39.5%), while the highest proportion for females was in the 61-year-old to 70-year-old age group (25.0%) (Figure 1C).

Follow-up and referral

After completing the serological tests, participants received screening resultsviatelephone calls.Participants with positive HBsAg or anti-HCV were referred to their local medical care facility(University of Minnesota Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition or Mayo Clinic Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology) for subsequent management, surveillance and/or treatment.Participants who were HBsAg negative and anti-HBs negative were referred to their local primary care clinic (Gargar Clinic and Urgent Care or Axis Medical Center) to complete the HBV vaccination series.

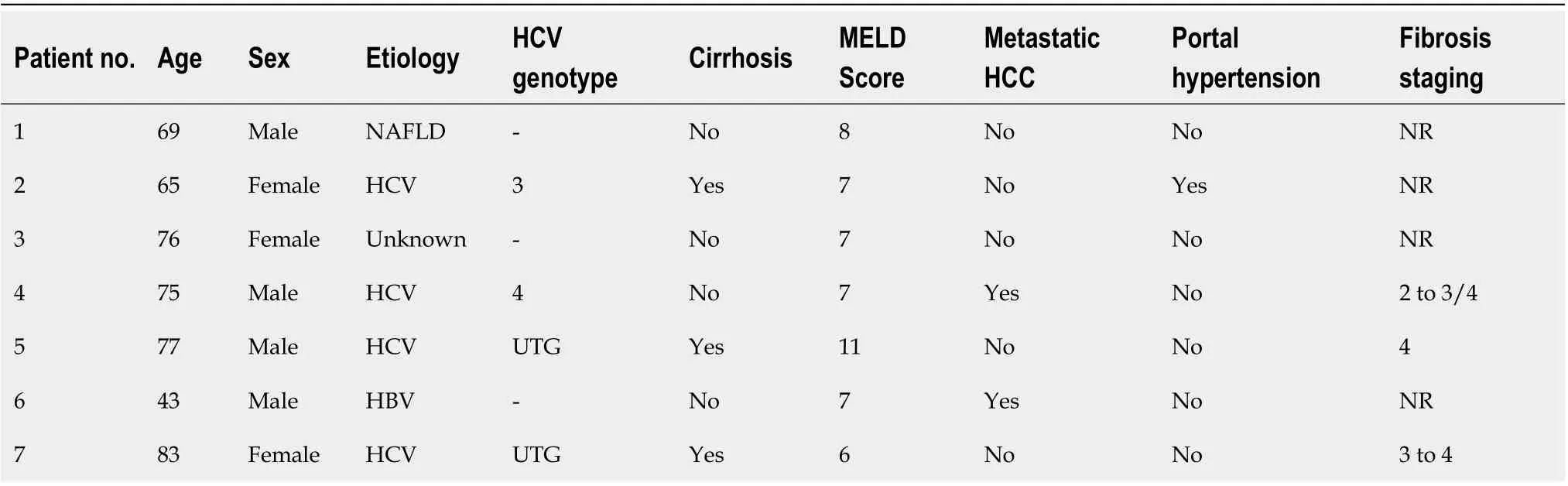

Characteristics of participants who developed HCC

After serological tests confirmed positive HBV and/or HCV infection or susceptibility to HBV infection,patients were linked to care for treatment or monitoring of their viral hepatitis, as appropriate, or for HBV vaccination. They were encouraged to notify the study staff if they were diagnosed with advanced liver disease or HCC. Seven individuals were identified by review of the medical records or patient selfreport to have HCC in follow-up after testing. Their ages ranged from 43 years to 83 years (mean 69.8 years; IQR 65.8, 76.8). Four were male (57%), and three (43%) were female. The most common etiology was HCV infection (n= 4; 57%); one patient had HBV infection (14%), one had non-alcoholic fatty liver disease without cirrhosis, and one had no known risk factor for HCC. Three of the 4 HCV HCC patients had cirrhosis (Table 4).

Due to the number of participants lost to follow-up, we do not have complete follow-up of the entire cohort of participants over the period and, therefore, were unable to calculate the exact incidence of HCC in the participants of this screening study. However, comparison to our previous retrospective hospital/clinic-based study, in which we found 30 Somali patients with HCC (2.5%) out of a total of 1218 patients tested for any chronic hepatitis markers, shows a lower incidence of 7 HCC cases (0.9%) of the 779 adults tested in this community-recruited cohort. This is not surprising, since the hospital/clinicbased cohort almost certainly had a selection bias for viral hepatitis or more severe chronic liver disease.

Table 3 Rates of hepatitis B virus vaccination and susceptibility in Community Recruited Minnesota Somali Residents

Table 4 Characteristics of 7 Somali participants who developed hepatocellular carcinoma

The observed incidence of 7 HCCs in the cohort of 779 adults prospectively tested in this study, albeit with incomplete follow-up over a median of approximately 8 years, is estimated to be 112 per 100000 person-years or 0.11% per year risk of HCC in the entire cohort. This is almost certainly an overestimate as some of the cases may have had unrecognized HCC at the time of initial testing.

DlSCUSSlON

The primary goal of our study was to examine the prevalence of HBV and HCV viral infections in the immigrant Somali community residing in Minnesota. As a secondary goal, we also ascertained any cases of HCC that developed in study participants by voluntary notification and review of available medical records. This study is the first of its kind to report the results of community-wide screening for HBV and HCV in this immigrant population. We found that 15.4% of participants had chronic HBV infection compared to the estimated United States general population prevalence of 0.4%[32]. HCV prevalence was 7.6%, also significantly higher than the general United States population prevalence of HCV which is less than 2%[33]. In comparison to our previously published results, this prospective study determined that chronic HBV rates are higher than the frequency reported in the 2012 clinic/hospital-based retrospective study[29].

Figure 1 Frequency in Somali Patients Screening. A: Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-positive test results; B: Prior exposure of HBV test results; C: Hepatitis C viruspositive test results. HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Somalis in Minnesota are younger than the general population with a median age of 25 years compared to the general population median age of 37 years[34]. Therefore, surveillance for viral hepatitis is important for this community. Given the high prevalence of HBV and HCV infections in Somalia noted in prior studies, a significant number of Somali immigrants are likely to have chronic hepatitis and are at risk for HCC. Yanget al[35] reported that African-born individuals diagnosed with HCC in the United States, particularly those of West African ancestry, are diagnosed at a younger age.Most of these individuals have chronic HBV infection, which was acquired in the first few years of life,and it is recommended that HCC surveillance of this group begin at the age of 20 years[5]. The Somali immigrant community may be different; in addition to high rates of chronic HBV infection, there is also a high prevalence of chronic HCV infection, most likely acquired during adulthood. A multi-center,multi-national, retrospective observational cohort study that investigated the current clinical presentation of Africans with HCC showed that in Egypt, where chronic HCV is the major etiology of HCC, the median age of HCC onset was 58 years, compared to 46 years in eight other African countries with a predominance of HBV-induced HCC[6].

While the high level of chronic HBV infection in the immigrant Somali population suggests an elevated risk of maternal-to-child transmission and horizontal transmission of HBV between family members at an early age, it is important to note that about a third of all the individuals we screened had evidence of prior exposure to HBV infection that they had cleared spontaneously. This phenomenon occurs most commonly in adults exposed to HBV infection and suggests substantial transmission of HBV among adolescents and adults in the community. Risk factors associated with these infections need to be identified and addressed. Individuals from areas affected by conflict and displacement are at a greater risk of contracting infectious agents, such as viral hepatitis infections[36]. For instance, Khanet al[37] reported that internally displaced individuals have high levels of HBV and HCV infections. This may reflect the lack of basic health infrastructure and services in refugee camps and displaced communities.

Shireet al[29] showed an increased frequency of HBV and HCV among Somali patients seen in the hospital/clinic setting, which could potentially have been due to selection bias. However, our community-based screening study of Somali immigrants in Minnesota confirms high rates of chronic HBV and HCV infection rates among this population. The best outcomes for communities with high prevalence of chronic HBV and HCV infections have been shown in Japan and Taiwan, which have comprehensive programs for screening all adults for chronic viral hepatitis and enrolling those at risk into surveillance programs for HCC. These programs have resulted in ≥ 70% of HCCs being detected at early stages when they are eligible for curative treatment. Consequently, the 5-year survival rate of patients diagnosed with HCC in these countries ranges from 50%-70%, substantially higher than the currently estimated rate of 15% in the United States[38]. Whether HCC surveillance decreases liver disease mortality is still controversial, but almost all international guidelines now recommend surveillance for HCC among high-risk patients using liver ultrasound performed every 6 mo with or without measurement of the serum alpha-fetoprotein[39-45]. There are active efforts underway to develop more sensitive and effective biomarker and imaging technologies for HCC surveillance. We are performing additional studies to assess the stage at diagnosis of HCC in the immigrant Somali community and discern any barriers or disparities in care related to chronic liver disease and HCC.

Furthermore, the observed incidence of 7 HCCs in the cohort of 779 adults prospectively tested in this study is estimated to be 112 per 100000 person-years or 0.11% per year risk of HCC in the entire cohort.This is almost certainly an overestimate as some of the cases may have had unrecognized HCC at the time of initial testing. By comparison, for the time period between 2012 and 2016, the age-standardized rates of liver cancer incidence in Minnesota were 5.7 per 100000 for Non-Hispanic Whites and 24.7 per 100000 for Blacks[46]. Since the total number of Somali adults aged 18-84 in Minnesota, estimated at 33208, represents approximately 23% of the 146020 adults of African descent aged 18-84 who are resident in Minnesota, the Somali immigrant community likely contributes substantially to the overall incidence of HCC in Minnesota[47,48].

The results of this study suggest a need to develop strategies to improve awareness of chronic hepatitis[49], increase screening for chronic HBV and HCV infections in the immigrant Somali community in the United States and promote hepatitis B vaccination in unvaccinated children and adults. These strategies could help prevent chronic liver disease and HCC, increase access to currently available treatments that suppress HBV viral load or cure HCV and substantially reduce the burden of hepatobiliary malignancies observed in Minnesota’s non-Hispanic Black population[50-52]. Ahmed Mohammedet al[53] reported that visits to gastrointestinal/hepatologist specialists were linked to increased HCC surveillance in Minnesota residents, as compared to primary care practitioner visits.Given the limitations in access to specialist care, efforts to encourage HBV and HCV testing of immigrant Somalis in the primary care setting could improve the early diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis and appropriate linkage to care.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The first limitation is selection bias and this is due to the nature of the study design. However, through the use of community advisory boards, community-based organizations and clinics, we are confident that our data can be generalizable to the larger Somali community of Minnesota. Second, loss to follow-up was another limitation associated with this study,especially for those individuals who have developed liver cancer and associated co-morbidities. On the contrary, there are several strengths associated with this study. First, the implementation of communityengagement through health education and listening sessions have ensured participants are informed of the goals of the study in a culturally sensitive and responsive framework. Second, building strong partnerships with community-based organizations, charter schools and clinics were instrumental in the success of recruitment and dissemination of information.

CONCLUSlON

Chronic HBV and HCV infections are prevalent among Somali immigrants in Minnesota and associated with high rates of HCC. Partnering with community stakeholders helped to improve recruitment rates and to spread awareness of the need for viral hepatitis screening. Community-wide screening is an effective way to identify and provide health education and linkage to care for individuals with or at risk for viral hepatitis. It is important to develop and implement culturally and linguistically acceptable viral hepatitis awareness programs in partnership with communities, in order to promote preventative vaccination, treatment of viral hepatitis and reduction of cancer risk.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

Somali immigrants come from regions of the world where viral hepatitis is endemic. Since the start of the Somali civil war in 1991, limited data is available on the impact of viral hepatitis in the community,especially those individuals in the diaspora.

Research motivation

The impetus of this project was communal outcry about community members succumbing to liver disease. In partnership with the community, our research team worked to assess the burden of viral hepatitis in Minnesota. Addressing this pressing communal matter, we were able to connect those who tested positive for hepatitis infections and/or were not vaccinated for hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the needed healthcare.

Research objectives

Our objective was to determine the prevalence of viral hepatitis infections within the community. This is significant because it laid the foundation to start conducting studies on host-viral interactions and the unique development of liver disease among this population. This is relevant to clinical practice because we can use this information to tailor screening practices and treatments for individuals from endemic regions which are historically under studied.

Research methods

In partnership with the community stakeholders, we conducted a prospective study using communitybased participatory research from 2010 to 2015. We screened for viral hepatitis infections and reported the results back to the study participant. This is the first study of its kind to screen community based Somali immigrants in Minnesota at a large scale.

Research results

Viral hepatitis infections are a major under recognized disease within the Somali immigrant population.Age-adjusted prevalence rates are high and call for prioritizing responses from health agencies. This data will be used to lobby public health institutions to help address the unique needs of the Minnesota Somali population and for healthcare providers to implement programs to screen community members for both HBV and hepatitis C virus. Furthermore, the follow-up after the patients have enrolled into the study was quite difficult. We should consider effective methods to follow-up patients to assess the potential for development of liver disease sequelae.

Research conclusions

Although there were limitations to the study, we have learned that chronic viral hepatitis infection in the Somali community is high. Effective screening programs need to be implemented in order to prevent suffering and needless death. The use of community-based participatory research was a success and was the first of its kind with this community regarding a disease considered taboo. We will continue this partnership and expand research within this population historically under reported in clinical research.

Research perspectives

We will continue maintaining the partnership and will continue to understand the unique host-viral interactions. We have studies on immunoprofiling as well as examining the influence of the viral genome on liver disease progression. These studies will be used to improve the health of persons from this region of the world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the study participants and their family members. In addition, the authors would like to thank the community partners who provided their community facilities to recruit,enroll, accrue and disseminate findings (i.e. Gargar Urgent Care and Clinic, Axis Medical Center,Masjed Abu Huraira, Masjed Al-Nur, Masjed Abubakr Al-Seddiq, and Mankato Mosque) and the Somali Health Advisory Committee, who ensured that we provided a culturally relevant and responsive manner in our efforts. In addition, the authors would like to thank Dr. Yu Wang, Dr. Chen-Chao Ma, the Mayo Clinic Clinical Trials and Research Unit and Lea Dacy for technical support.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Mohamed EA, Giama NH, Abdalla AO, Shire AM, Shaleh HM, Oseini AM, Ali HA, Ahmed F,Taha W, Ahmed Mohammed H, Cvinar J, Waaeys IA, Ali H, Allotey LK, Ali AO, Mohamed SA, Harmsen WS,Ahmmad EM, Bajwa NA, and Afgarshe MD, Balls-Berry JE, and Roberts LR contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation of data; Mohamed EA, Giama NH, Abdalla AO, and Shire AM drafted the manuscript; Shaleh HM, Oseini AM, Ali HA, Ahmed F, Taha W, Ahmed Mohammed H, Cvinar J, Waaeys IA, Ali H, Allotey LK, Ali AO, Mohamed SA, Harmsen WS, Ahmmad EM, Bajwa NA, Afgarshe MD, Balls-Berry JE, and Roberts LR contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript; All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Supported bythe Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (5UL1TR000135-10); the Mayo Clinic Hepatobiliary SPORE from the National Cancer Institute(5P50CA210964-04); the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (5P30DK084567-14); and Gilead Sciences, Inc. (IN-US-174-0230).

lnstitutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (19-001670).

Clinical trial registration statement:This study does not include any interventions and is not a randomized controlled trial. The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.Gov (NCT02366286).

lnformed consent statement:Written informed consent was obtained from study subjects prior to enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at Roberts.Lewis@mayo.edu. No additional data are available.

CONSORT 2010 statement:The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 Statement.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non

commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORClD number:Essa A Mohamed 0000-0002-0307-6241; Nasra H Giama 0000-0003-2764-866X; Abubaker O Abdalla 0000-0002-7022-1074; Hassan M Shaleh 0000-0002-4698-4610; Abdul M Oseini 0000-0003-4079-9825; Hamdi A Ali 0000-0002-2671-0532; Fowsiyo Ahmed 0000-0002-0201-6706; Wesam Taha 0000-0002-6737-3739; Hager Ahmed Mohammed 0000-0002-3731-4332; Jessica Cvinar 0000-0003-4855-6908; Ibrahim A Waaeys 0000-0003-2086-5477; Hawa Ali 0000-0003-4667-5233;Loretta K Allotey 0000-0002-5734-8839; Abdiwahab O Ali 0000-0003-1692-9829; Safra A Mohamed 0000-0001-8408-0017;William S Harmsen 0000-0001-7134-5362; Eimad M Ahmmad 0000-0002-1120-2631; Numra A Bajwa 0000-0002-2727-8710;Mohamud D Afgarshe 0000-0001-9066-0237; Abdirashid M Shire 0000-0002-8216-9971; Joyce E Balls-Berry 0000-0003-3497-1115; Lewis R Roberts 0000-0001-7885-8574.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年35期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年35期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Hepatitis B viral infection and role of alcohol

- Urotensin ll level is elevated in inflammatory bowel disease patients

- Correction to “l(fā)nhibiting heme oxygenase-1 attenuates rat liver fibrosis by removing iron accumulation”

- Dynamic blood presepsin levels are associated with severity and outcome of acute pancreatitis: A prospective cohort study

- Gut microbiota of hepatitis B virus-infected patients in the immunetolerant and immune-active phases and their implications in metabolite changes

- Natural history and outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis complicated by hepatic hydrothorax