Natural history and outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis complicated by hepatic hydrothorax

Sarah Romero, Andy KH Lim, Gurpreet Singh, Chamani Kodikara, Rachel Shingaki-Wells, Lynna Chen,Samuel Hui, Marcus Robertson

Abstract BACKGROUND Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is an uncommon and difficult-to-manage complication of cirrhosis with limited treatment options.AIM To define the clinical outcomes of patients presenting with HH managed with current standards-of-care and to identify factors associated with mortality.METHODS Cirrhotic patients with HH presenting to 3 tertiary centres from 2010 to 2018 were retrospectively identified. HH was defined as pleural effusion in the absence of cardiopulmonary disease. The primary outcomes were overall and transplant-free survival at 12-mo after the index admission. Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to determine factors associated with the primary outcomes.RESULTS Overall, 84 patients were included (mean age, 58 years) with a mean model for end-stage liver disease score of 29. Management with diuretics alone achieved long-term resolution of HH in only 12% patients. At least one thoracocentesis was performed in 73.8% patients, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt insertion in 11.9% patients and 33% patients received liver transplantation within 12-mo of index admission. Overall patient survival and transplant-free survival at 12 mo were 68% and 41% respectively. At multivariable analysis, current smoking[hazard ratio (HR) = 8.65, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.43-21.9, P < 0.001) and acute kidney injury (AKI) (HR = 2.91, 95%CI: 1.21-6.97, P = 0.017) were associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality.CONCLUSION Cirrhotic patients with HH are a challenging population with a poor 12-mo survival despite current treatments. Current smoking and episodes of AKI are potential modifiable factors affecting survival. HH is often refractory of diuretic therapy and transplant assessment should be considered in all cases.

Key Words: Cirrhosis; Portal hypertension; Hepatic hydrothorax; Ascites; Liver transplantation

lNTRODUCTlON

Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is an uncommon but serious complication occurring in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. HH is defined as the accumulation of more than 500 mL of transudative pleural fluid in a patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, where primary cardiopulmonary or malignant aetiologies have been excluded[1]. HH has been reported to occur in 5% to 11% of patients with cirrhosis, with more than 90% of cases occurring in Child-Pugh B or C disease[1,2]. HH is thought to arise from direct passage of fluid from the peritoneal cavity to the pleural cavity through diaphragmatic fenestrations[1]. Nuclear medicine studies, using labelled albumin have confirmed unidirectional passage of fluid from the abdominal to the pleural cavity[3], thus supporting a diaphragmatic defect process.

Clinically significant HH develops when accumulation of ascites in the pleural cavity exceeds the absorptive capacity of the pleura and patients typically present with shortness of breath, cough, hypoxia or chest discomfort[1,3]. Most cases occur in patients with appreciable ascites, however ascites may not be a prominent finding in up to 42%[1]. HH is most often unilateral and right-sided (59%-80%),however, there are increasing reports of left-sided (12%-17%) or bilateral (8%-24%) involvement[1,4].Similar to the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in patients with ascites, patients with HH may develop spontaneous infections within the pleural fluid, which are termed spontaneous bacterial empyema (SBEM)[3].

The clinical management of HH remains complex and challenging. Treatment priorities in cirrhotic patients presenting with a pleural effusion include confirming a diagnosis of HH and excluding alternative pathology, relieving symptoms, preventing pulmonary complications and managing the underlying ascites. Diagnostic or therapeutic thoracocentesis is typically performed to confirm the presence of transudative fluid and to exclude SBEM or alternative pathology[5]. Recently developed American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) guidelines state that first-line management should include sodium restriction and diuresis[6]. It is recognised, however, that 20%-30% of patients with cirrhosis and HH will develop persistent or recurrent pleural effusion despite these measures[6]. Refractory HH represents a particularly challenging management issue and patients are often considered for repeat therapeutic thoracocentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement. Liver transplantation (LT) is the definitive treatment for HH, and posttransplant outcomes are comparable to outcomes for alternative indications[6].

Currently, there remains a paucity of literature examining the natural history and prognostic significance of HH. No randomised controlled trials have been performed in this population and clinical guidelines were only published for the first time in 2020[6]. Previous small studies have indicated the development of HH is associated with significant morbidity and extremely poor survival in the absence of LT[2,7,8]. The aims of this study were to: (1) Evaluate the probability of survival in a cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis presenting with HH and to examine factors associated with mortality; and(2) Provide a descriptive analysis of the treatments and complications associated with HH treatment during hospitalisation.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

We conducted a multi-centre retrospective cohort study of patients with cirrhosis and HH presenting to three Australian metropolitan tertiary hospitals, one of which was a liver transplant centre, over a 9-year period from 2010 to 2018. Across all study sites, patients with decompensated cirrhosis were admitted under a specialist gastroenterology or liver transplant unit. Individual patient management was at the discretion of the attending gastroenterologist.

Ethics approval

The Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash Health and Austin Health approved the study as a quality assurance activity and the committee provided a waiver for informed consent (RES-19-0000-343Q).

Study participants

International Classification of Diseases (10threvision) codes for cirrhosis and chronic liver disease (K74,K74.6), HH (J 94.8) and pleural effusion (J90, J91) were used to retrospectively identify eligible patients with cirrhosis and HH[9]. The study eligibility criteria were: (1) Adult patients ≥ 18 years; (2) A confirmed diagnosis of cirrhosis, either biopsy-proven or based on clinical complications of cirrhosis; (3)Confirmed diagnosis of pleural effusion, based on imaging (plain X-ray or computed tomography); (4)Evidence of portal hypertension, as established by the presence of oesophageal varices, ascites and/or thrombocytopenia; and (5) Exclusion of cardiopulmonary or malignant pathology as a cause for the pleural fluid collection. Eligible patients were excluded if they had previously undergone LT. Included patients were followed for 12-mo from the date of the index admission.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were 12-mo overall and transplant-free patient survival following index hospital admission with HH. Patients were followed-up from the date of first hospital admission with HH to an endpoint of death, LT or end of the study period. We report the 12-mo overall survival using the endpoint of death, censored for LT; and the 12-mo transplant-free survival using a composite endpoint of death and LT. The secondary outcomes included the incidence of specific treatments of HH and associated complications and to determine patient-specific prognostic factors associated with mortality.

HH definition and treatment protocols

HH was defined as the presence of a pleural effusion occurring in a patient with liver cirrhosis where no alternative aetiology was identified. Each patient was reviewed by a specialist hepatologist to ensure that the aetiology of pleural effusion was secondary to HH. Patients were excluded if the pleural effusion was felt to be due to primary infection, cardiopulmonary or malignant pathology.

Paracentesis was performed following radiological marking and thoracocentesis was performed by an interventional radiologist or the unit treating doctor with ultrasound guidance. In all cases, baseline observations were recorded, and the procedure was performed using sterile technique. Intravenous albumin (100 mL of 20% concentrated human albumin) was administered after every 2 liters of ascites or pleural fluid drained as per institutional protocol. Clinical observations were performed every 30 min for the duration of the procedure. Pleural and ascitic fluid was sent for analysis at the discretion of the physician performing the procedure according to indication and specimen viability. Where available,serum-pleural ascites gradient (SPAG) or serum-ascites albumin gradient values were obtained. SPAG greater than 11 g/L is consistent with a transudate[2], and was used to confirm portal hypertensive pathophysiology. SBEM was defined as pleural fluid with polymorphonuclear count of > 500 cells/mm3or > 250 cells/mm3with a positive culture, where parapneumonic effusion had been excluded[3].Thoracocentesis without significant fluid drainage (diagnostic aspiration) was not considered in this analysis. TIPS insertion was available at all study centres and was performed by interventional radiology.

Treatment modalities pertaining to HH were categorized as: (1) Medical therapy with diuretics,and/or thoracocentesis; (2) TIPS; and (3) LT. All patients were risk stratified using the model for endstage liver disease (MELD) score which was calculated at the time of presentation for each admission.An in-hospital complication was defined as the occurrence of one or more of the following: Infection,procedural complication (hematoma, pneumothorax, death), acute kidney injury (AKI, defined as at least 1.5-1.9 times baseline or ≥ 26.5 mmol/L increase from baseline[10]), and new-onset acute hepatic encephalopathy which was not present on admission.

Data sources

For each patient, baseline demographic data, aetiology of liver disease, comorbidities, medication use,radiology results and laboratory results were extracted from electronic medical records. For patients with recurrent hospital admissions due to HH during the study period, data was collected for each presentation. Death was determined through hospital medical records and confirmed with a patient’s Local Medical Officer if required.

Statistical analysis

mean ± SD was used to describe normally distributed continuous data, and median and interquartile range (IQR) for data that was significantly skewed.χ2analysis was used to examine the association between categorical variables. For the primary outcome, we used the Cox proportional hazards regression survival model to analyze the time of onset of HH to death. The time at risk begins at the first admission for HH (the index admission, t0) and patients were censored at the time of LT or study conclusion (365 d after t0). For transplant-free survival analysis, we omitted censoring LT and treated the transplant date as an outcome event. For each readmission, further clinical data was collected for analysis. The model incorporates enduring baseline variables (age, sex, comorbidities, smoking, alcohol intake, aetiology of cirrhosis) as well as a number of time-varying covariates (MELD score, AKI, encephalopathy, treatment-related complications, functional status, and TIPS).

From the univariable analyses, we included variables with aP< 0.20 into the multivariable model.Through backward elimination steps, we retained covariates with aP< 0.05 and checked the general model fit using partial Cox-Snell residuals. We used fractional polynomials to assist parameterization of continuous variables. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the Schoenfeld residuals. The DFBETA estimates were used to detect influential observations. To validate our findings,we conducted bootstrapping of the Cox regression analysis with 1000 replications to generate bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were conducted with STATA 16.1 (StataCorp, TX,United States), and aP< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

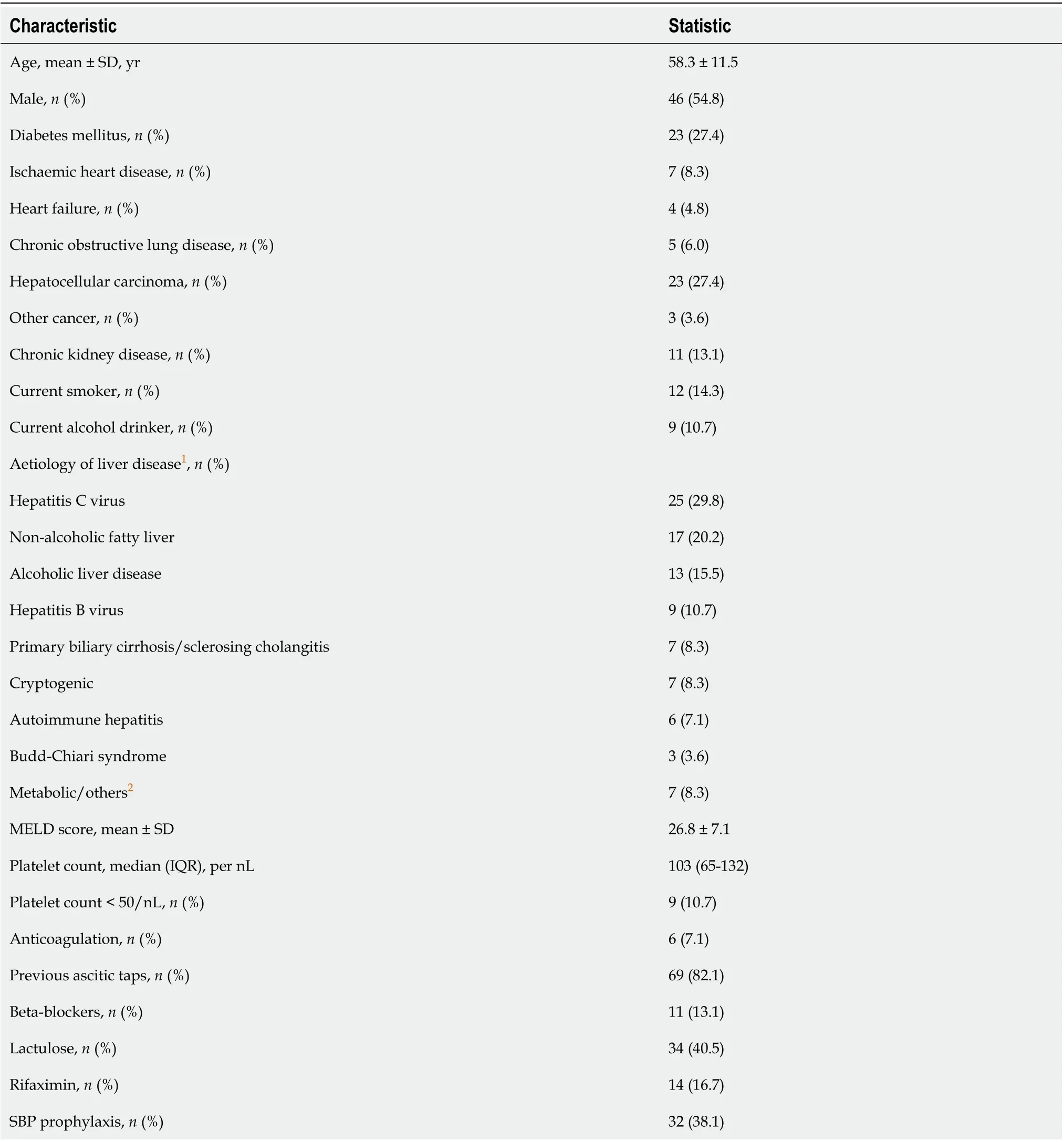

A total of 246 patients with cirrhosis presenting to hospital with a pleural effusion were identified during the study period, of which 162 were excluded as the pleural effusion did not meet the criteria for HH. The final analysis included 84 patients who had a total of 167 hospital admissions over the study period. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58.3 years, with only 11% patients over the age of 70, and there was a slight predominance of males. All patients had established liver cirrhosis and clinical evidence of portal hypertension. The median MELD score at time of hospital admission was 29 (IQR: 25-33). A diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was present in 27.4% patients.

Across all hospital admissions, 59% of patients were treated with lactulose (13% variation within patients between admissions), 27% of patients were treated with rifaximin (average 12% variation within patients between admissions), and 56% of patients were receiving prophylaxis for SBP (average 12% variation within patients between admissions). Prior to hospital presentation with HH, 93%patients were prescribed diuretic therapy, with median furosemide and spironolactone doses of 40 mg and 100 mg per day respectively and 70% of these patients were receiving dual diuretic treatment.

HH clinical features and management

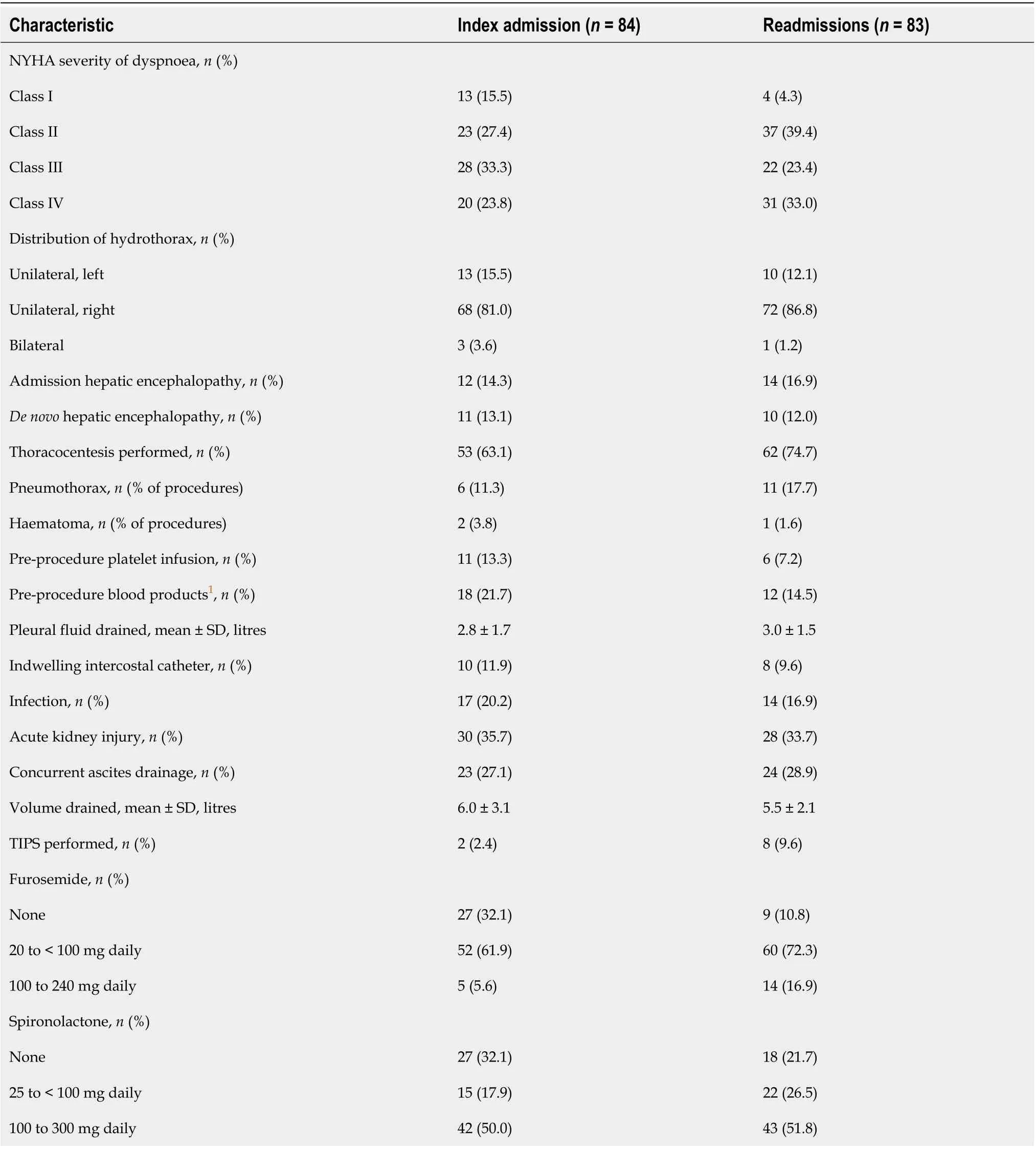

The clinical features and management of HH are summarized in Table 2. The majority of the hydrothoraces were unilateral on the right side. Of the 167 episodes of HH, 20 (12.0%) were managed solely with increased diuretics. Concurrent treatment with diuretics and ascitic fluid drainage was commonly performed, with abdominal paracentesis performed during 47 (28.1%) presentations, where the median volume of fluid drained was 5 litres. The proportion of patients requiring thoracocentesis,abdominal paracentesis and the complications rates were similar for readmissions compared to the index admission. However, the dose of diuretics used was higher on readmissions than during the index admission.

Thoracocentesis and complications:In total, 115 thoracocentesis procedures were performed in 62(73.8%) patients with a median of 3 litres drained per procedure. Thoracocentesis was performed in 53 of 84 (63%) patients during the index admission. A further 62 thoracocentesis procedures wereperformed in 33 of 43 patients who required one or more readmissions. On average, the probability of receiving another thoracocentesis was 77% during each readmission episode. Sufficient laboratory data to perform pleural/ascitic fluid analysis was available in 31% of procedures. Of these, SBEM was detected in 10 (8.7%) thoracocentesis procedures.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients with cirrhosis during the index hospital admission for hepatic hydrothorax (n = 84)

Blood products, including pooled platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, were administered in 29% of patients prior to or following thoracocentesis. Sixteen patients received an indwelling intercostal catheter for ongoing drainage rather than simple thoracocentesis in the setting of acute instability (n= 4) or refractory disease (n= 12). A pneumothorax complicated 17 (15%) thoracocentesis procedures, of which 7 were managed conservatively, 9 required an intercostal catheter insertion, and 1 patient died. Bleeding complications from thoracocentesis were uncommon and we could not determine if blood product infusions (platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin complexconcentrate) reduced procedural complications or affected patient survival.

Table 2 Clinical features of hepatic hydrothorax, management, and complications

Other complications:One or more non-pleural complications were recorded in 80 (48%) of HH admissions. The most frequent complications were AKI in 58 (35%) patients, followed by infection in 31(19%) and new-onset hepatic encephalopathy in 21 (13%). The incidence of these complications was similar for the index admission and readmissions.

TIPS insertion:Ten (12%) patients received a TIPS insertion, with 2 patients receiving TIPS insertion during the index admission, and 8 patients on a readmission. Significantly more females than males received a TIPS (21%vs4%,P= 0.038), but age and MELD score did not differ between patients who received TIPS and those who did not. No patient who received a TIPS proceeded to LT within 12 mo of the index admission.

LT: Forty-seven patients (56%) were referred for liver transplant assessment and 28 patients (33%) were successfully transplanted in the 12-mo following their index admission. The median time to transplantation from the index admission was 105 d (IQR: 55-200 d). The effect of LT on survival could not be estimated as there were no deaths amongst the transplanted patients within the study period.

Hospital length of stay and readmissions

The median hospital length of stay was 8 d (IQR: 4-17) for the index admission and 6 d (IQR: 4-14) for subsequent hospital readmissions. Within 12-mo of the index admission, 22 (26%) patients had 1 readmission, 9 (11%) had 2 readmissions, and 12 (14%) had ≥ 3 readmissions. In the 43 patients who required readmission, the median time interval between the index admission and the first readmission was 32 d (IQR: 12-74 d). The primary reasons for hospital readmissions were recurrent hydrothorax in 24 (38%) patients and decompensated cirrhosis in 26 (41%). There was strong evidence for an association between the New York Health Association (NYHA) functional class of dyspnoea and total number of readmissions (χ2= 46.2,P< 0.001) but the strength of the association was weak (Kendall’s tau-b= 0.11).Intensive care unit (ICU) admission was required in 13 (15%) patients during the index admission, and 10 (12%) of 83 readmission episodes.

Mortality

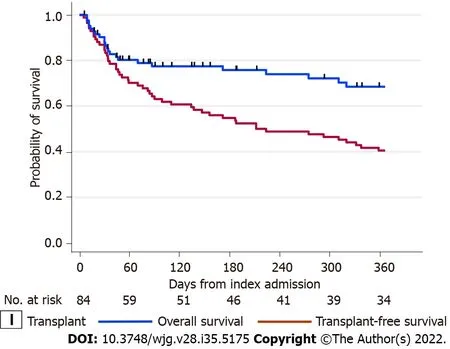

There were 23 deaths (27.4% of the cohort) within 12-mo of the index admission. The total time-at-risk was 17850 patient-days with a mortality rate of 1.3 deaths per 1000 patient-days. The Kaplan-Meier survivor functions for overall and transplant-free patient survival are shown in Figure 1. Most deaths occurred early after the index admission, with 30-d overall survival of 87% (95%CI: 78%-93%), 45-d survival of 80% (95%CI: 70%-87%), and 12-mo survival of 68% (95%CI: 56%-78%). For transplant-free survival, the 30-d survival was 85% (95%CI: 75%-91%), 45-d survival of 76% (95%CI: 66%-84%), and 12-mo survival of 41% (95%CI: 30%-51%). Most deaths were due to complications of end-stage liver disease and multiorgan failure (75%) or hepatocellular carcinoma (10%), but a small number were due to cardiovascular events (15%). We noted that the mortality rate for current smokers was 5.58 per 1000 patient-days, compared to non-smokers of 0.86 per 1000 patient-days, giving a mortality rate ratio for current smokers of 6.5 (95%CI: 2.5-16.1,P< 0.001).

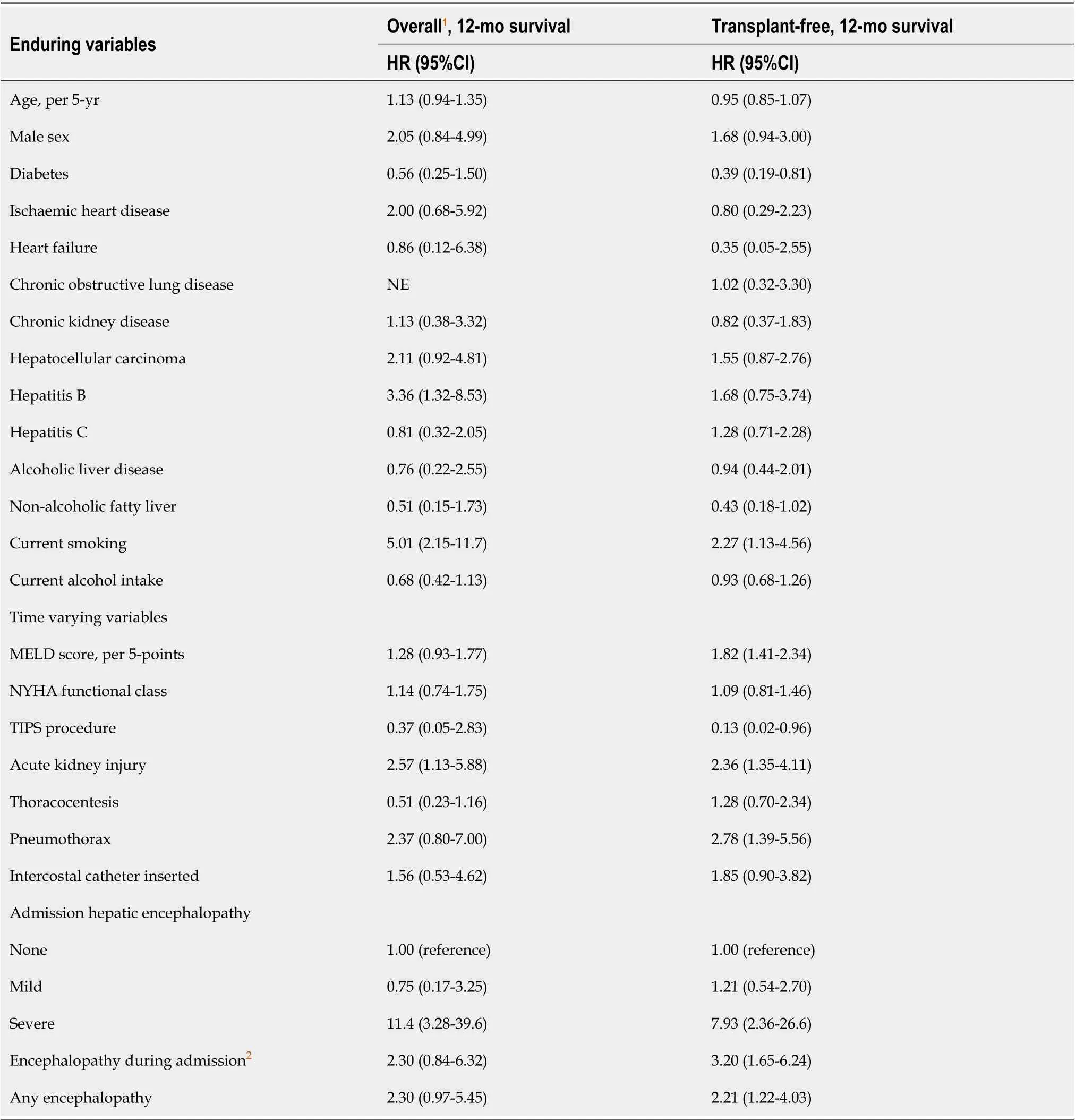

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis

The results of univariable analyses are summarised in Table 3. Factors consistently associated with an increased hazard of death were current smoking, episodes of AKI, higher MELD score, and hepatic encephalopathy. In addition, when analysing transplant-free survival, diabetes and TIPS insertion were associated with a lower hazard for death or LT while incident pneumothoraces were associated with greater hazard.

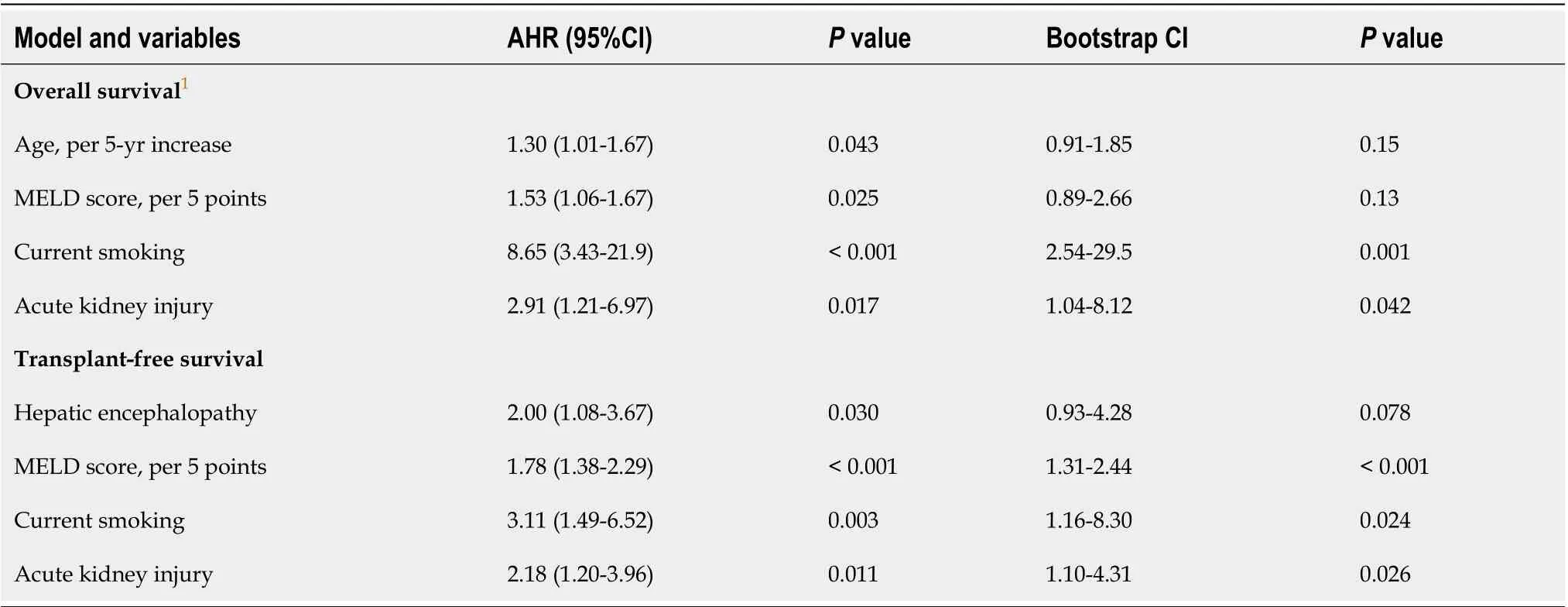

The results of the multivariable analyses are summarised in Table 4. When examining the overall patient survival model, we decided not to include hepatic encephalopathy in the multivariable model as there were only 4 cases of severe encephalopathy on admission which were associated with an increased risk of death. In the transplant-free survival model, age, diabetes, TIPS and incident pneumothoraces were not statistically significant after adjusting for MELD, smoking, AKI, and hepatic encephalopathy.There were no significant statistical interactions between variables in the final models, and the models were a reasonable fit for the data when assessed by partial Cox-Snell residuals.

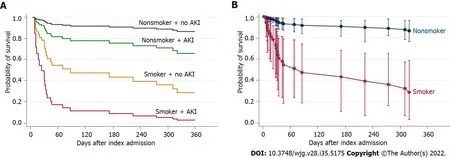

Due to the cohort size, we conducted bootstrapped analysis to validate our findings (Table 4). The significance of current smoking and AKI remained robust. In the overall survival model, a current smoker had 8.7 times the hazard of death of a non-smoker or ex-smoker; and one or more episodes of AKI was associated with a 2.9-fold increase in the hazard of death, after allowing for age and MELD score. In the transplant-free survival model, a current smoker had 3.1 times the hazard of death of a non-smoker or ex-smoker; and AKI was associated with a 2.2-fold increase in the hazard of death; after allowing for MELD and hepatic encephalopathy. These findings are represented in Figure 2.

Other analysis

To compare with the traditional Cox model, we also performed a competing risks regression analysis(Fine-Gray subdistribution proportional hazards) using the same covariates, with the assumption that all patients were on the active liver transplant waiting list. In this analysis, the effect of smoking and AKI on survival remained significant, and our conclusions remained unchanged. The subhazard ratio(SHR) of smoking on mortality was 6.26 (95%CI: 2.75-14.3),P< 0.001. The SHR of AKI on mortality was 2.60 (95%CI: 1.25-5.36),P= 0.01. The clear effect of smoking can be illustrated by examining the cumulative incidence function for active smokers compared to non-smokers (see Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 3 Univariable Cox regression on patient survival to 12 mo

DlSCUSSlON

HH remains an uncommon but extremely challenging complication in patients with liver cirrhosis. This study represents one of the largest series to analyse the natural history and outcomes of patients with HH and to our knowledge, is the first study to examine factors associated with survival in this population. We demonstrated that development of HH was associated with poor prognosis despite current therapeutic modalities, with a 45-d overall survival of 80% and 12-mo transplant-free survival of 41%. HH is a refractory disease, and the use of diuretics in isolation was rarely effective in this cohort,with 52% of patients experiencing recurrence of HH and rehospitalisation. At multivariable analysis,smoking status and the presence of AKI confer significant additional mortality risk.

Table 4 Multivariable Cox regression on patient survival to 12 mo

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing transplant-free survival at 12 mo, with liver transplantation and death treated as composite endpoints, and overall patient survival at 12 mo, with patients censored at the time of liver transplantation (ticks on survival curve).

Hospitalisation with symptomatic HH is an uncommon presentation, with 84 patients recruited over a 9-year period to 3 metropolitan tertiary hospitals. The majority of patients presented with a rightsided pleural effusion and concurrent ascites, which is consistent with previous series[1,2,4]. The median MELD score of 29 in our cohort highlights that HH typically occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis who often have other decompensating events such as hepatic encephalopathy. The median MELD score in our study was higher than that reported in other smaller studies[2,4,11], which may reflect use of data from a LT centre.

Patient management in this study aligns with recent AASLD guidelines, which recommend diuresis as the first-line therapy[6]. Most patients in our study were receiving diuretic therapy at the time of hospital presentation, with 70% receiving 2 diuretic agents, however the median doses of furosemide and spironolactone was well below the recommended maximum doses of 160 mg and 400 mg daily respectively[1]. Nonetheless, only 12% patients achieved long-term resolution of HH with diuretic therapy alone. An important limiting factor in relation to diuretic therapy is the propensity for AKI in patients with advanced cirrhosis. AKI was recorded in nearly one-third of presentations, and this was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality. This suggests that diuretic therapy should be titrated cautiously in patients with HH with close monitoring of renal function.

Figure 2 Multivariate survival analysis. A: Multivariable Cox regression of overall patient survival (censored for transplantation), showing survival estimates for patients with hepatic hydrothorax by smoking and acute kidney injury status, with age and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores held at the mean values;B: Bootstrapped pointwise confidence intervals for survival functions by active smoking status, in the absence of acute kidney injury and with age and MELD held at the means, demonstrating a robust association between active smoking and mortality in patients with hepatic hydrothorax. AKI: Acute kidney injury.

There remains no consensus on universal diagnostic thoracocentesis in hospitalised patients with HH.In practice, whilst HH may be suspected on the basis of imaging and clinical presentation, thoracocentesis is useful to confirm transudative fluid and exclude other causes of a pleural effusion. We demonstrated that thoracocentesis in the HH population was associated with a significant higher risk of pneumothorax of 15% compared to the standard pneumothorax risk of 6% in non-cirrhotic populations,despite being performed under ultrasound guidance[12]. Shojaeeet al[13] reported that repeat thoracocentesis in cirrhotic patients was associated with a higher rate of major complications compared to thoracocentesis for other aetiologies (8%vs0%). In addition, Xiolet al[5], observed a pneumothorax rate of 25% in cirrhotic patients undergoing serial therapeutic thoracocentesis. Our analysis suggested that pneumothorax complications were associated with lower transplant-free survival [hazard ratio (HR) =2.78; 95%CI: 1.39-5.56], however this was not significant in multivariable analysis. Other series have also suggested that HH requiring thoracocentesis independently confers significant morbidity and increased mortality[7,14]. Given the greater complications associated with thoracocentesis in cirrhotic patients, it was concerning that 74.7% of patients who were readmitted underwent repeat thoracocentesis. Further study is needed to elucidate the cause of the high complication rate and strategies to mitigate this risk.For example, it remains unclear if abdominal paracentesis effectively prevents HH recurrence[1].

In relation to other treatment modalities, indwelling intercostal catheter drains are thought to carry substantial risk and are not recommended by current guidelines, with some studies observing complication rates of 80%-90%[11,15]. In our cohort, an indwelling intercostal catheter was placed in 19% of patients, most commonly due to respiratory compromise and rapid re-accumulation of pleural fluid. In contrast, consideration of TIPS insertion is recommended by AASLD guidelines, based on evidence of a 70%-80% response rate in patients with refractory HH[3,6,16-18]. The outcomes following TIPS insertion may be comparable to those for management of refractory ascites and although a survival benefit in HH has not been established[19], the study by Badillo and Rockey[2] suggests a trend toward improved survival in patients proceeding to TIPS. Only 10 (17.9%) of the 56 patients in our cohort who were deemed not suitable for LT received TIPS insertion. No overall survival benefit from TIPS insertion was demonstrated, but transplant-free survival was higher (HR = 0.13; 95%CI: 0.02-0.96), as no patient who had TIPS insertion underwent LT.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that development of HH is associated with a poor prognosis[2,20,21], but mortality is difficult to compare due to heterogeneity between studies[2,4,11,15,21,22]. Our 12-mo transplant-free survival of 41%, however, is comparable to the 12-mo mortality of 57% reported by Badillo and Rockey[2]. In multivariable analysis, increasing age and MELD score, hepatic encephalopathy, development of AKI and active smoking were important factors independently associated with mortality. Given that the majority of deaths in our cohort were observed within 45-d of hospital admission and were most frequently due to complications of end-stage liver disease, we would advocate that in all patients presenting with HH, the appropriateness of transplantation should be considered with early referral for suitable candidates. Indeed, no deaths were recorded in patients who received LT, highlighting the successful outcomes of transplantation in patients with HH.

The strong association between smoking and poor outcomes has not previously been reported in patients with HH. Our study echoes a growing body of literature demonstrating an association between cigarette smoking and poorer outcomes in patients with liver disease[23,24]. Current smokers with cirrhosis have up to a 3.6 times higher mortality risk and cigarette smoking has been linked with progression of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[24], hepatitis C and primary biliary cholangitis and is associated with an increased incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma[23]. Cigarette smoking represents an important modifiable risk factor that should be actively addressed in all patients with cirrhosis but appears critical in the HH population.

Study strengths and limitations

This is one of the largest, multicentre studies to investigate the prognostic significance of HH requiring hospitalisation in cirrhotic patients. Study inclusion criteria were broad and pragmatic, and represent generalisable real-world data. The Victorian Liver Transplant Centre was established in 1988 and currently performs over 100 transplants annually. The cohort had comprehensive assessments by gastroenterology specialists to confirm HH, which also assured treatment consistent with current standard-of-care practice guidelines. We used multivariable analysis to allow for confounders of mortality, and were able to identify smoking as a novel factor associated with significantly lower 12-mo survival in patients with HH. This study was able to elucidate the less well-described challenges in HH patients, such as need for ICU admission, hospital readmissions, and blood product requirement.

This study is limited by its retrospective design, with the inherent risks of missing information or extraction of inaccurate records. Complete pleural fluid analysis was only available in 31% of patients,which limited our ability to detect complications such as SBEM. SBEM has been associated in other studies with high short-term mortality (20% to 38%)[1]. SBEM was detected in 8.7% of thoracocentesis procedures in our study, which is almost certainly an underrepresentation of the true rate and lower than a study by Xiolet al[5], which found SBEM was present in 13% of patients with HH on presentation. Reasons for the low rate of complete pleural fluid analysis included the large number of hospital settings in which thoracocentesis was performed (including the emergency department, ICU,gastroenterology ward, radiology department or other acute hospital wards) with associated heterogeneity in process, incorrect requests for fluid analysis, incorrect tube collection to facilitate fluid analysis, clotting of fluid which precluded analysis, emergency procedures due to patient distress or instability and thoracocentesis performed prior to a diagnosis of HH being made. This reflects the realworld nature of the study and pleural fluid analysis rates were similar across all study sites. As such, we were not able to determine if specific pleural fluid findings were associated with refractory symptoms,rehospitalisation, or poor survival. In addition, factors associated with treatment failure or rehospitalisation such as compliance with diuretics were difficult to discern. The observational nature of the study also limits any causality inferences and eliminates the ability to ensure standardisation, which is particularly relevant to thoracocentesis technique. We could not exclude the possibility that some patients may have been admitted to a non-study hospital, although in practice this would be uncommon, and thus readmissions and complications may be underestimated.

In order to assess if TIPS may have provided clinical benefit apart from survival, we examined the readmissions, thoracocentesis, or ascitic drainage procedures in patients who received TIPS. Four patients had a single readmission post-TIPS, of which 3 occurred < 30 d and one at 6 mo post-TIPS.Thoracocentesis was performed in 3 of 4 of these readmitted patients, and ascitic drainage in 1 of 4 of these readmitted patients. Due to these low frequencies and different timing of TIPS, we cannot provide a meaningful statistical comparison with patients who did not have TIPS.

CONCLUSlON

The development of HH is associated with poor transplant-free survival despite current standards-ofcare and should prompt consideration of the appropriateness of LT in all patients. HH is often refractory to both conservative and invasive management and patients frequently require repeat hospitalisations. Active smoking and AKI may be important modifiable risk factors to reduce mortality in cirrhotic patients with HH.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is an important complication of cirrhosis, however management is often challenging and the natural history is poorly understood.

Research motivation

HH is a significant complication of cirrhosis, with a paucity of literature studying natural history and factors affecting survival.

Research objectives

This study sought to: (1) Evaluate factors associated with survival in a cohort of patients hospitalised with HH; and (2) Provide descriptive analysis of treatments, complications and outcomes following HH hospitalisation.

Research methods

Cirrhotic patients with HH presenting to three tertiary centres from 2010 to 2018 were retrospectively identified. Patients were followed-up from the date of first hospital admission with HH to an endpoint of death, liver transplantation (LT) or end of the study period. The primary outcomes were overall and transplant free survival at 12 mo after the index admission. The secondary outcomes included the incidence of specific treatments of HH and associated complications and to determine patient-specific prognostic factors associated with mortality.

Research results

Only 12% of patients achieved long-term resolution of HH with diuretic therapy alone. 74% of patients required thoracocentesis, with 15% of procedures being complicated by pneumothorax. 12-mo transplant free survival was 41%. 45-d overall survival was 80%.

Research conclusions

The development of HH is associated with poor transplant-free survival despite current standards-ofcare and should prompt consideration of the appropriateness of LT in all patients. HH is often refractory to both conservative and invasive management and patients frequently require repeat hospitalisations. Active smoking and acute kidney injury may be important modifiable risk factors to reduce mortality in cirrhotic patients with HH.

Research perspectives

This study represents one of the largest series examining survival in persons hospitalised with HH, and importantly has identified modifiable risk factors that may alter the natural history in this challenging patient population.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Romero S, Lim AK and Robertson M performed literature review, data analysis and interpretation and manuscript composition and critical revision; Lim AK, Robertson M and Hui S conducted statistical analysis; Romero S, Singh G, Kodikara C, Shangaki-Wells R and Chen L performed data acquisition;Robertson M was responsible for study concept and design; and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

lnstitutional review board statement:The Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash Health and Austin Health

approved the study as a quality assurance activity and the committee provided a waiver for informed consent (RES-19-0000-343Q).

lnformed consent statement:The informed consent was waived by the Human Research Ethics Committee.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at s.romero.md@gmail.com. Patient consent was not obtained for this study, however study data has been anonymised.

STROBE statement:That authors have read the STROBE statement-checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Australia

ORClD number:Sarah Romero 0000-0003-2707-6390; Andy KH Lim 0000-0001-7816-4724; Gurpreet Singh 0000-0001-6760-566X; Chamani Kodikara 0000-0002-2381-2875; Rachel Shingaki-Wells 0000-0002-8714-591X; Lynna Chen 0000-0002-7093-2036; Samuel Hui 0000-0002-2839-6209; Marcus Robertson 0000-0002-8848-1771.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年35期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年35期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Hepatitis B viral infection and role of alcohol

- Urotensin ll level is elevated in inflammatory bowel disease patients

- Correction to “l(fā)nhibiting heme oxygenase-1 attenuates rat liver fibrosis by removing iron accumulation”

- High prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis B and C in Minnesota Somalis contributes to rising hepatocellular carcinoma incidence

- Dynamic blood presepsin levels are associated with severity and outcome of acute pancreatitis: A prospective cohort study

- Gut microbiota of hepatitis B virus-infected patients in the immunetolerant and immune-active phases and their implications in metabolite changes