Bridging the mental health treatment gap: effects of a collaborative care intervention (matrix support) in the detection and treatment of mental disorders in a Brazilian city

Sonia Saraiva , Max Bachmann, Matheus Andrade, Alberto Liria

ABSTRACT

Objective To analyse temporal trends in diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care following implementation of a collaborative care intervention (matrix support).

Design Dynamic cohort design with retrospective time- series analysis. Structured secondary data on medical visits to general practitioners of all study clinics were extracted from the municipal electronic records database. Annual changes in the odds of mental disorders diagnoses and antidepressants prescriptions were estimated by multiple logistic regression at visit and patient- year levels with diagnoses or prescriptions as outcomes. Annual changes during two distinct stages of the intervention (stage 1 when it was restricted to mental health (2005—2009), and stage 2 when it was expanded to other areas (2010—2015)) were compared by adding year—period interaction terms to each model.

Setting 49 primary care clinics in the city of Florianópolis, Brazil.

Participants All adults attending primary care clinics of the study setting between 2005 and 2015.

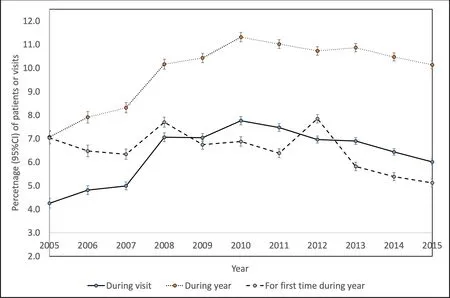

Results 3 131 983 visits representing 322 100 patients were analysed. At visit level, the odds of mental disorder diagnosis increased by 13% per year during stage 1 (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.14, p<0.001) and decreased by 5% thereafter (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.94 to 0.95, p<0.001). The odds of incident mental disorder diagnoses decreased by 1% per year during stage 1 (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.00, p=0.012) and decreased by 7% per year during stage 2 (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.93, p<0.001). The odds of antidepressant prescriptions in patients with a mental disorder diagnosis increased by 7% per year during stage 1 (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.20, p<0.001); this was driven by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescriptions which increased 14% per year during stage 1 (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.18, p<0.001) and 9% during stage 2 (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.10, p<0.001). The odds of incident antidepressant prescriptions did not increase during stage 1 (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.02, p=0.665) and increased by 3% during stage 2 (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.04, p<0.001). Changes per year were all significantly greater during stage 1 than stage 2 (p values for interaction terms <0.05), except for antidepressant prescriptions during visits (p=0.172).

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 35%—50% of people with mental disorders in high— income countries and 76%—85% in low— income and middle— income countries receive no treatment, what results in avoidable suffering, disability and economic loss.12Anxiety and depres—sive disorders have the highest estimated lifetime rates, of about 16% and 12%, respectively.2Low— income and middle— income countries are hit harder due to a combination of low educational and socioeconomic attainment among the patients, poor work conditions of practitioners and inefficient use of resources, which are mostly invested in psychiatric hospitals despite the associ—ation of these settings with poor health outcomes.1

Brazil is more affected than other low— income and middle— income countries, with mental disorders present in 29.6% of adult S?o Paulo residents—of whom two— thirds receive no treatment3—and over half of adults attending Petrópolis primary care (PC) practices.4The combina—tion of low recognition, diagnostic inaccuracy and low treatment offer in primary care practice may contribute to a treatment gap.5Integrating mental health (MH) care into PC provision will improve the effectiveness of care by providing opportune access and early treatment while reducing associated stigma.1This requires from primary care practitioners (PCPs) new knowledge and skills to identify, manage and refer mental disorders; and from MH providers, new roles of advising and support to PCPs.15Several integration approaches have been tested; of these, collaborative care has the strongest evidence base.6—8

Collaborative care interventions aim to develop closer work relationships and improve continuity of care between PCPs and specialist providers, based on a multi— professional approach to care, structured manage—ment plans and patient follow— up, and enhanced inter— professional communication.7—9That is usually operated through advice and support from specialists to general practitioners (GPs) in the form of clinical discus—sions, case management and specialist care to selected patients.71011Successful implementation relies on organ—isational support to identify training needs and barriers, review professional roles and provide feedback about the integration.1011

A number of high— quality trials and systematic reviews have shown that collaborative care is more effective than standard care for depression and anxiety,6is cost— effective when compared with usual care,8and has positive effects in terms of case detection, treatment offer, clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.6—810Most studies were conducted in experimental settings of the USA and the UK,7and little is known about collaborative care in the PC practice settings of low— income and middle— income coun—tries. Conducting studies in such settings may improve understanding of how successful research interventions are translated into real— world contexts.

Brazil, a middle— income country which has one of the world’s largest universal health systems, has increased access to healthcare in the last two decades through the Family Health Strategy (FHS), an approach to PC based on multi— professional teams with a doctor (general physi—cian), nurse, nursing assistant and community health workers responsible for catchment areas of 3000—4000 people.12Within primary care, mental health profes—sionals are integrated into the PC teams through the matrix support model, a locally adapted collaborative care model which aims to increase access to care and co— or—dination.13Matrix support was piloted in a few cities in the early 2000s as an MH intervention and, from 2008, it was expanded to other areas like rehabilitation and nutri—tional care and scaled up as the federally funded NASF programme (original acronym for Family Health Support Teams), which had over 4000 teams implemented in 2016.

The matrix support intervention integrates key features of collaborative care like multi— professional care, enhanced communication and structured follow— up, to local innova—tions like joint consultations between MH professionals and PCPs. Key similarities between the models are the centrality of enhanced communication and collaborative clinical work between providers.1314Table 1 summarises the components and activities of matrix support.

Previous studies suggested that the Brazilian matrix support model might have similar effects to other collaborative care models mentioned in the literature, for example, improving detection of mental disorders, co— ordination between MH and PC providers,15and overall quality of PC teams.16However, so far, there are no published evaluations of matrix support using routine services data. This study aimed to analyse the associa—tion between implementation of matrix support in the Brazilian city of Florianópolis and the detection andtreatment of mental disorders by PCPs between 2005 and 2015, as well as to compare two distinct stages of the inter—vention, as a mental health— only programme and as part of the NASF programme, through statistical analysis of electronic medical record (EMR) data.

Table 1 Key components and activities of the matrix support intervention

METHODS

Study setting

Florianópolis is a state capital in the south of Brazil of 500 973 inhabitants in 2019.17Primary care is based on the FHS model, and it was expanded from 48 FHS teams in 2005, covering 42% of an estimated 394 285 inhabitants, to 150 teams in 2015 covering 100% of 469 690 inhabi—tants. All residents are assigned to one of 49 municipal PC clinics in each of which work 1 to 6 FHS teams providing preventive care, nursing care, medical treatment, free medicines, preventive care and referrals. The city has long been recognised for the coverage and quality of primary care and mental health care1819and was awarded a Ministry of Health’s prize for its matrix support inter—vention.20Despite these achievements, the local health system faces constraints similar to other low— income and middle— income countries, like insufficient staff, poor physical structure and unequal access to healthcare.21

Implementation of the intervention

Matrix support was implemented in Florianópolis initially as an MH intervention (2005—2009) and further as part of the NASF programme (from 2010). These two periods correspond to two distinct stages of the matrix support intervention. In stage 1, the outpatient's referral system to MH professionals was replaced by regular meetings between PC and MH teams, in which both jointly agreed and monitored treatment plans and performed collabo—rative activities like case discussions or joint visits. Those meetings were also used to on— site training through discus—sion of diagnostic criteria for mental disorders, screening during routine consultations and feedback about the GP referrals to mental health professionals. Communication by phone or email between the meetings was encour—aged, and selected patients were seen by the MH team or referred to MH services. A dedicated programme manager with MH background provided on— site support to the clinical and administrative integration.1820

In stage 2, with funding from the NASF programme, the MH professionals were integrated into the broader NASF teams, where they needed to share the restricted time of the PC teams with other professionals like physio—therapists and dietitians.22The programme management was decentralised to middle managers who were already in charge of several other PC programmes, so less support was available for the integration between MH and PC professionals. Previous studies have stressed the impor—tance of management support to successfully imple—menting matrix support, through integrating distinct professionals’ agendas, guaranteeing regular meetings, and dealing with continuity gaps and communication problems.2324Therefore, less support for clinical integra—tion was likely to negatively impact on the outcomes of the matrix support intervention.

Study design

This was a programme evaluation with a dynamic cohort design, that is, participants could enter and leave the cohort at any time, with a retrospective time— series analysis of outpatient attendances at health centres (PC clinics). The primary units of analysis were individual patients and their attendances (visits). Data were extracted from a consolidated EMR database, which registers all patient visits to the services of the city’s Municipal Health Secre—tary. Structured data including age, gender, ICD—10 diag—nostic code and drug prescriptions are recorded by all PC workers for each individual visit and then automati—cally consolidated at clinic and system levels. Data were included while each PC clinic implemented the EMR system, which was expanded during the study period (from 13 clinics in 2005 to 49 in 2015).

Study population

Patients aged 18 years or over who had at least one visit to a GP in a PC clinic with the EMR system imple—mented between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2015 were included. Visits to non— medical PC personnel, for example, nurses, were not included because although these professionals also participated in matrix support activities like case discussion and on— site training, they were not directly responsible for the diagnosis and treat—ment of patients with mental disorders. Visits to non— PC services were not included because these services were not part of the intervention.

Outcomes

The following measures of detection and treatment of mental disorders by GPs were built on the available data, the intervention objectives and the mentioned previous research on collaborative care.

? Detection of mental disorders: the proportion of all visits in which any mental disorder diagnosis was recorded; the proportion of all patients attending during each calendar year in whom any mental disorder diagnosis was recorded during the same year; the proportion of all patients attending during each calendar year in whom any mental disorder diagnosis was recorded for the first time during the same year (‘incident diagnoses’). The ‘proportion of visits’ reflects changes in the workload of the GPs with mental disorders, while the ‘proportion of patients’ assesses whether more distinct patients with mental disorders were seen since the same patient might have several visits.

? Treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders: the proportion of all visits with a diagnosis of anxiety or depressive disorder recorded in which an antidepres—sant was prescribed during the same visit; the propor—tion of all patients who attended during a calendar year with an anxiety or depressive disorder diagnosed to whom an antidepressant was prescribed during the same year; the proportion of all patients who attended during a calendar year with an anxiety or depressive disorder diagnosed to whom an antidepressant was prescribed for the first time during the same year (‘incident treatments’). These outcomes are proxy indicators of access to treatment of these mental health conditions in primary care.

Anxiety and depressive disorders are generally viewed as the main remit of PC5and are particularly frequent in Brazil.4Both antidepressants and psychotherapy are effective treatments for most anxiety and depressive disorders, but only antidepressants (tricyclics and selec—tive serotonin reuptake inhibitors—SSRIs) were regularly provided in the study clinics and had consistent records in the EMR database. SSRIs are associated with fewer side effects on depression treatment and are usually prefer—able to tricyclics for anxiety disorders.25Therefore, an analysis by antidepressant class was added to assess if any increases in treatments were driven by SSRIs, expressing adequacy of treatments. The analysis of prescriptions at visit and patient levels followed the same rationale explained previously for detection.

Each outcome was analysed for the whole period of study (2005—2015) and for each intervention stage sepa—rately. Date limits were established on an annual basis (stage 1: 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2009; stage 2: 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2015).

Data collection and management

Data on outcomes measures and baseline variables were extracted from the EMR database by one of the authors with authorisation of the Municipal Secretary of Health (local health authority) and securely stored at the Univer—sity of East Anglia. Only secondary anonymised data were used. The authors had no access to patient identifiers.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for baseline variables. Statistical analyses aimed to estimate annual changes in the odds of mental disorders being recorded during a GP visit or during a patient— year, and in the odds of antidepres—sants being prescribed for visits of patients with anxiety or depressive disorders, or in a patient— year with anxiety or depressive disorder. Diagnosis of a mental disorder was defined as the recording of an ICD—10 code with an F prefix and of anxiety and depressive disorders as ICD—10 codes F32—39 plus F40—48. Antidepressant prescrip—tions were defined as any tricyclic or SSRI prescriptions recorded. For analyses of incident diagnoses or treat—ments recorded for the first time during a year, patients were removed from the denominator population at risk if they had had the same diagnosis or treatment in previous years. The 95% CIs for proportions of patients or visits with each outcome were estimated with adjustment for clustering of outcomes within patients.

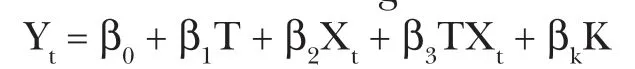

The effects of the intervention on outcomes were esti—mated using segmented interrupted time series regres—sion models.26The regression model equations were:

where T represents the year, Xtis a dummy variable indicating stage 1 (coded 0) or stage 2 (coded 1), Ytrepresents the outcome at year t, β0represents the base—line level at year 0, β1represents the change in outcome associated with an additional year during stage 1, β2represents the baseline difference in intercept for stage 2 time trend, β3is the change in time trend from stage 1 to stage 2 and βkis the vector of coefficients corresponding the other covariates K.26TXtis thus an interaction term with a value of zero during stage 1 and a value of T during stage 2, and the time trend during stage 2 was obtained by multiplying β1and β3. Modelling time as a continuous avoids the problem of time— stage collinearity and enables different trends to be estimated for each stage. All models included age and sex as covariates, used robust adjustment for intra— patient correlation of outcomes and included dummy variables for each clinic to account for intra— clinic correlation of outcomes. Modelling clinics as covariates is equivalent to multilevel modelling with randomly varying intercepts for clinics. Multilevel mixed regression models with both clinics and patients as random effects could not be computed because of the large sample with over 3 million records. A 5% significance level was used. Statis—tical analysis was done with Stata V.16.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

There were 3 131 983 visits of adults (median age 46 years) to GPs in the study clinics between 2005 and 2015, of whom 207 314 (6.6%) had mental disorders recorded. Antidepressants were prescribed in 45.7% of the visits where anxiety or depressive disorder diagnosis was recorded. A total of 322 100 patients attended the visits, of whom 58 179 (18.0%) had a mental disorder ever recorded, and 46 378 (14.4%) had an anxiety or depres—sive disorder ever recorded. Women comprised 68.7% of patients with mental disorders, and 74.7% of patients with anxiety or depressive disorders.

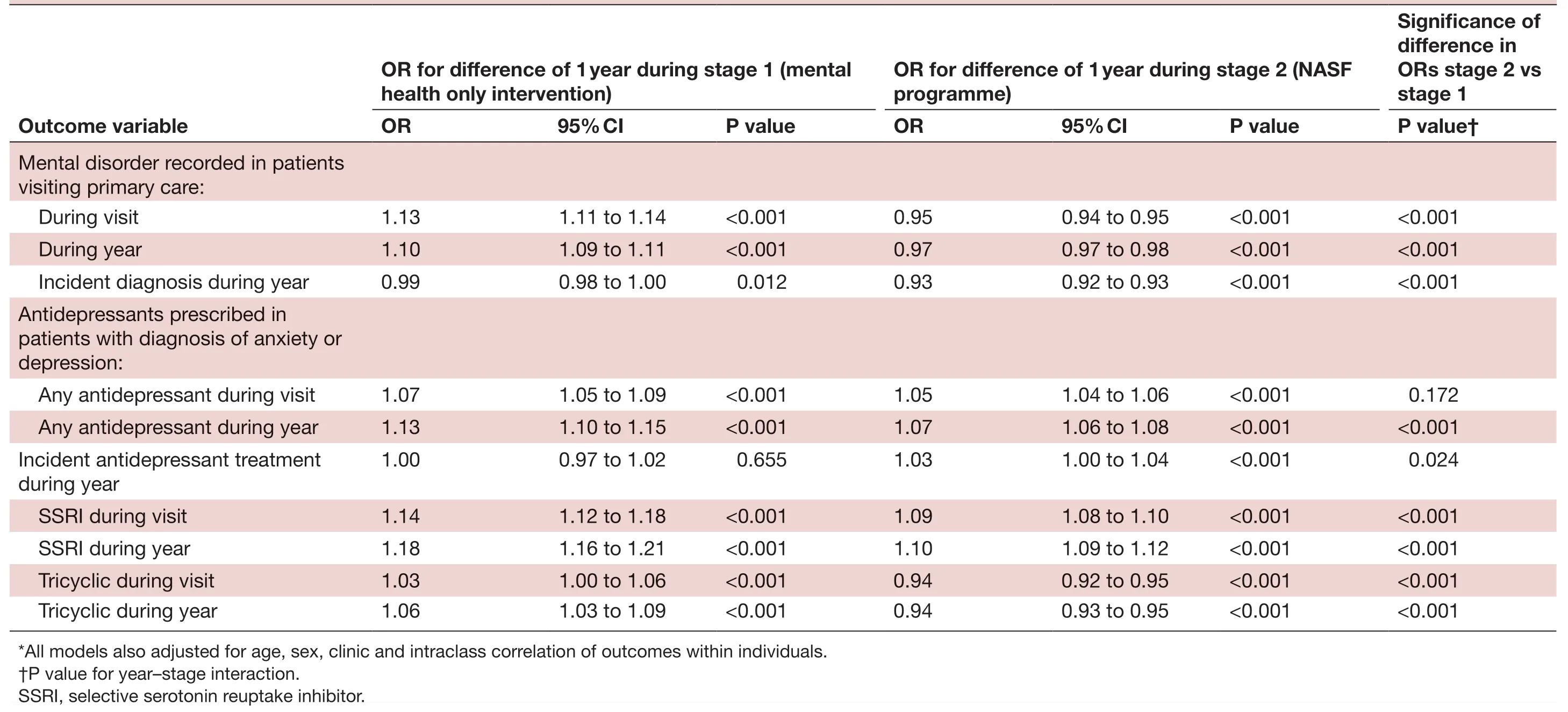

Detection of mental disorders

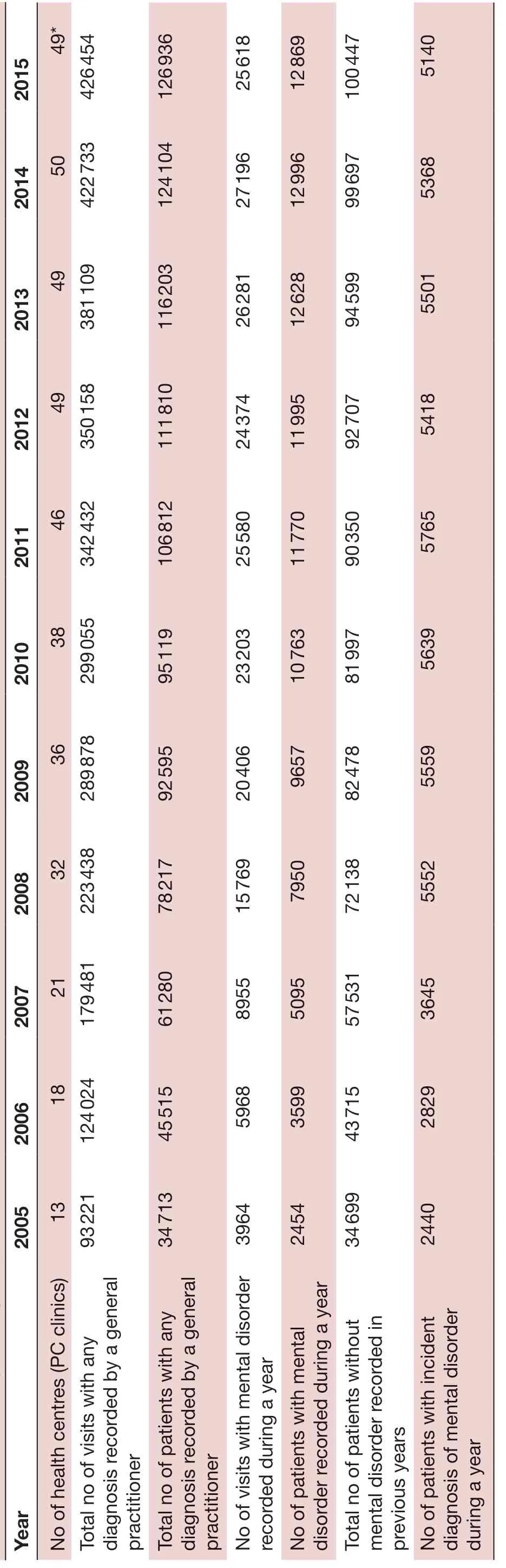

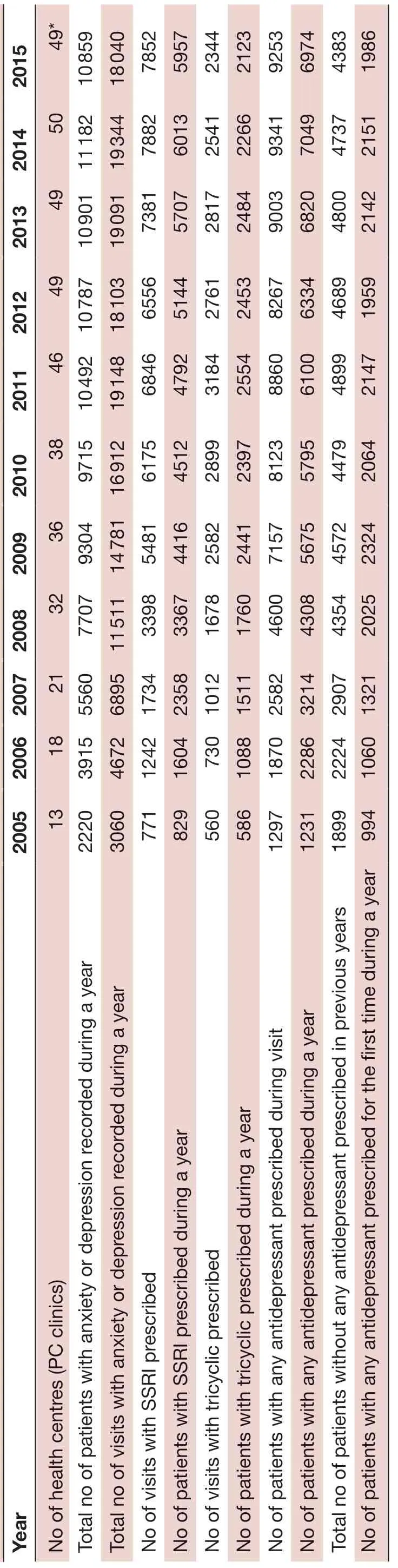

The proportions of visits and patients in which mental disorders diagnosis were recorded increased from 2005 to 2010 and decreased after that (table 2, figure 1). Considering the entire period, from 2005 to 2015, there was no change each year in the odds of a mental disorder being recorded at any visit (OR 1.00 95% CI 1.00 to 1.00, p<0.441), after adjustment for gender and age.

In the comparison between intervention stages, the odds of visits having a mental disorder recorded during a visit increased by 13% per year during stage 1 and decreased by 5% per year during stage 2 (p for year—period inter—action <0.001) (table 3). The odds of patients seen by a GP during a year having a mental disorder recordedduring the same year increased by 10% per year in stage 1 and decreased by 3% per year in stage 2 (p for year—stage interaction <0.001). The odds of incident mental disorder diagnoses decreased by 1% per year during stage 1 (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.00, p<0.012) and decreased by 7% per year during stage 2 (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.93, p<0.001).

Table 2 Frequency of diagnosis of mental disorders over time

Prescription of antidepressants

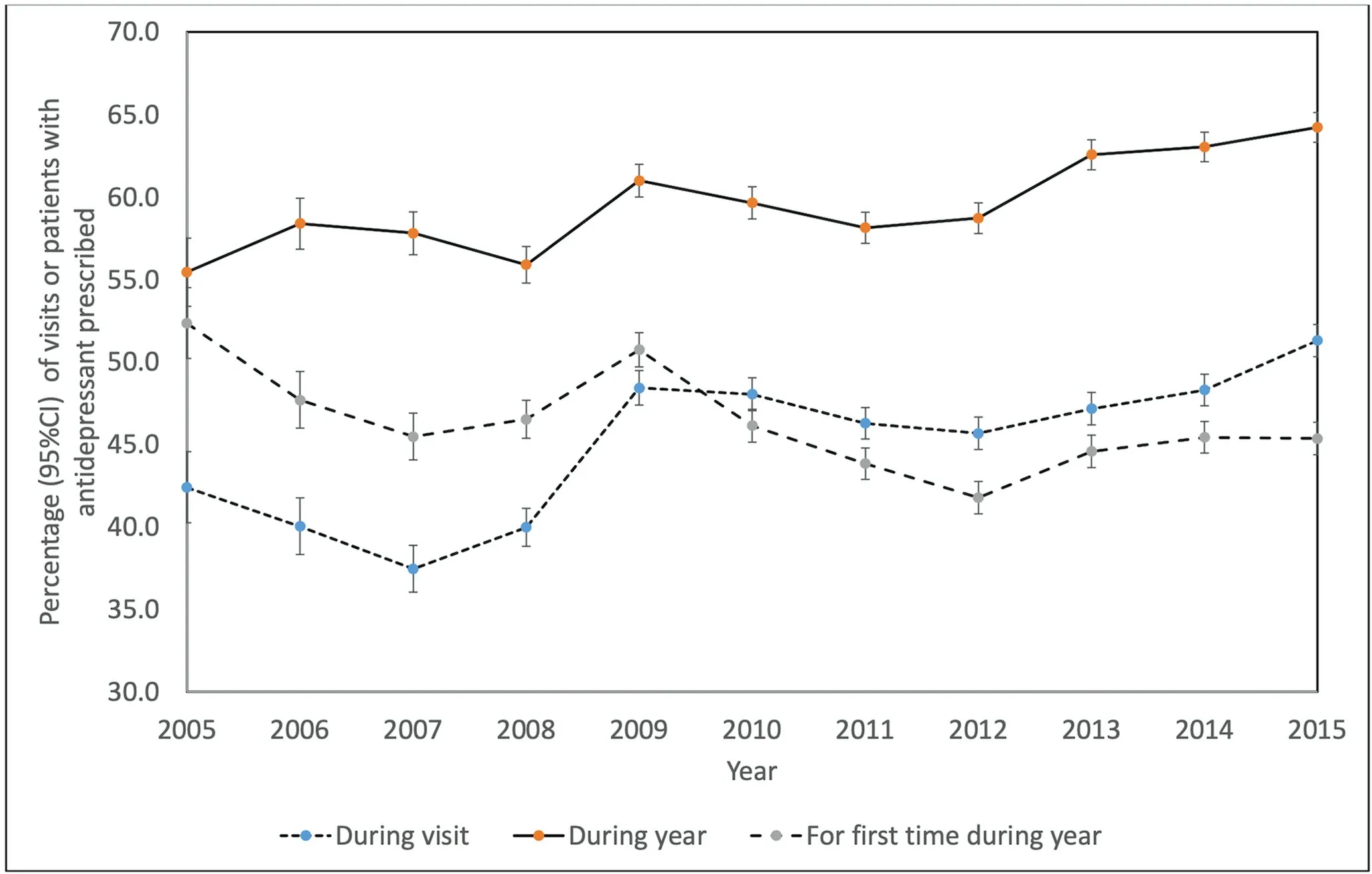

Among visits where a diagnosis of anxiety or depressive disorder was recorded, the probability of an antide—pressant being prescribed increased between 2005 and 2015 overall (table 4, figure 2). The odds of visits with an anxiety or depressive disorder recorded in which an antidepressant was prescribed increased by 19% per year during stage 1 and increased less rapidly, at 5% per year, during stage 2 (p for interaction=0.172) (table 3). In the analysis at patient— year level, the odds of any anti—depressant being prescribed during a year increased by 13% per year during stage 1 and by 7% during stage 2 (p for interaction <0.001). The odds of incident antidepres—sant prescriptions did not increase during stage 1 (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.02, p=0.665) and increased by 3% during stage 2 (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.04, p<0.001).

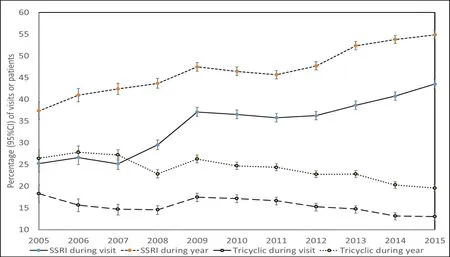

Splitting by antidepressant class, between 2005 and 2015, the probability of an SSRI being prescribed increased and the probability of tricyclics being prescribed decreased, in both visits and patient— year levels of analysis (table 4, figure 3). There was an 8% increase in SSRI prescrip—tion and a 2% decrease per year in tricyclics prescription during visits over the whole period. There was a 10% increase per year in SSRI prescription and a 1% decrease per year in tricyclics prescription during patient— years. The prescription of tricyclics was independently more likely in older and female patients (adjusted OR 1.08 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.09) per 10 years of age and 1.35 (95% CI 1.26 to 1.46), respectively, in visits; and 1.13 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.15) per 10 years of age and 1.37 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.46), respectively, during patient— years.

In the comparison between stages of the intervention, the odds of SSRI prescription during any visit increased by 14% per year during stage 1 and by 9% per year during stage 2 (p for year—stage interaction <0.001) (table 3). Tricyclic prescribing during visits increased by 3% per year during in stage 1 and decreased by 6% per year during stage 2 (p for interaction <0.001). In analysis at patient— year level, the odds of SSRI prescription during a year increased by 18% per year during stage 1 and by 10% per year during stage 2 (p for year—period interaction <0.001). Tricyclic prescription during a year increased by 6% per year in stage 1 and decreased by 6.6% per year during stage 2 (p for year—period interaction <0.001).

DISCUSSION

Figure 1 Mental disorder diagnosis per visit and per patient, 2005–2015.

This is the first study that reports mental health outcomes of the matrix support intervention based on routinely collected health services data. The results of stage 1 (2005—2009) suggest that the matrix support between MH and PC professionals when implemented with on— site support for clinical and administrative integration was associated with improved detection of mental disorders and improved treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. The same temporal trends were observed in the analysis at visits and patient— year levels, meaning that more distinct patients were diagnosed and treated for mental disorders in this period. These results are consistent with the matrix support overall goal of increasing access to care and with previous research on collaborative care.710During stage 1, both diagnosis of mental disorders and SSRI prescribing increased, but during stage 2 both diagnosis and tricyclic prescribing decreased, while SSRI prescribing increased at a lower rate. The main changes in the intervention from stage 1 to stage 2 which could explain such different results were the reduction of organisational support to services inte—gration, and the increasing competing demands to the primary care teams with the expansion of matrix support to other areas beyond mental health. These factors should have reduced the intensity or quality of the clin—ical collaboration between MH and PC professionals. This interpretation should be made with caution due to the number of possible intervening factors. Although the study design did not allow causal inference, its scale and pioneering, and the relevance of the matrix support for Brazil’s health system, make the findings of interest to policy— makers, managers and practitioners involved in integrating MH and PC, in Brazil and countries with similar health systems.

Sample features and recording issues

The predominance of middle— aged women was consistent with previous research conducted among PC attendees in Brazil, which show that being a woman was the socio—demographic variable most associated with the chance of receiving MH care.27This predominance might be explained by less dependence on others to access the services when compared with younger or older people, as well as a reduced perception of stigma associated with seeking MH care when compared with men.28

The finding of anxiety and depressive disorders as main diagnoses also followed the pattern usually observed in community surveys.3The rates of mental disorders (18.0%) and anxiety and depressive disorders (14.4%) in our sample were lower than reported in other studies in PC populations; for example, one study in four major Brazilian cities found prevalence of anxiety and depres—sion in adults attending PC clinics between 35%—43% and 21%—31%, respectively.27This difference in our findings may be due to methodological issues, rather than lack of recognition.29Most services surveys use standardised diagnostic instruments, which are associated with higher diagnosis rates of mental disorders when compared with records of routine clinical practice.30One survey in Brazil found that only 5.6% of PC attendees had a psychiatric diagnosis recorded, while 44.1% had an anxiety or depres—sive disorder according to a standard instrument.31Some reasons for this issue are high comorbidity, problems presenting in undifferentiated forms, and the preference of the GPs for recording symptoms or physical condi—tions as reasons for visits instead of assigning a psychiatriclabel to patients, especially those with mild symptoms or social distress.2932This is especially relevant, considering that the EMR data obtained for this study only informed one ICD—10 code per visit. Ultimately, the analysis of GP records might say more about the provision of care than the prevalence or the need in the population.

Table 3 Patient and visit level analyses: changes in odds of recorded diagnosis of mental disorder and prescription of antidepressants during stage 1 and stage 2: logistic regression models*

Table 4 Frequency of antidepressant prescriptions over time

Increase in detection and treatment of mental disorders

The prevalence of mental disorders is relatively stable in people presenting to PC,30meaning that the increasing records observed in stage 1 reflect increased recogni—tion of patients with mental disorders and, potentially, increased access to care. The increase in diagnoses during year or visit, together with no increase in incident diagnoses, suggests that patients in whom a diagnosis has already been made are having their mental disorder increasingly recognised by GPs at subsequent visits. Trends for antidepressants are similar; the small increase in incident treatments in stage 2 may represent patients previously recognised being now treated.

While higher recognition might occur at the expenses of oversensitivity and lack of specificity, and not neces—sarily improve patient outcomes,33a systematic review showed that non— psychiatric physicians indeed have low sensitivity (36.4%) and high specificity (83.7%) for diagnosing ‘true’ cases of depression, as defined by stan—dardised diagnostic instruments.32The increase in anti—depressant prescription observed mostly in stage 1 also reflects improved access to care. The use of antidepres—sant prescriptions alongside diagnostic codes to define depression was shown to improve case extraction from EMR data and be a better reflection of recognition by GPs,29what may be due to GPs’ recording preferences discussed earlier.32It remains an open debate to what extent GPs underdiagnose depression or instead avoid medicalising normal human distress.3033

The increase in antidepressant prescription was driven by SSRIs, while tricyclics decreased, as observed in other collaborative care studies.6Increased antidepressant use is a worldwide phenomenon associated with broader soci—etal factors, including the availability of new drugs, broad—ening of indications and advertising strategies.34In major Brazilian cities, most people taking psychotropic drugs do not have mental disorders, while most people with mental disorders remain without treatment,35a paradox also observed in other countries.28In PC settings, overtreat—ment with antidepressants is more related to prolonged use than to inadequate indication.36GPs tend to continue prescriptions once they have started, for reasons which include patient pressure, time constraints and lack of treatment alternatives.37The combination of societal trends and GP habits might explain why SSRI prescrip—tions still increased in stage 2, despite reduced detection of mental disorders.

Distinct outcome patterns across stages of the intervention

Figure 2 Antidepressant prescriptions per visit and per patient, 2005–2015.

The decrease of diagnoses and reduced treatment increase observed in stage 2 might be explained by differences in organisational support and intensity of collaborative work after the introduction of the NASF programme. In stage 1, the matrix support had a dedicated manager offering on— site support to clinical integration, mediation of administrative problems and feedback about outcomes, for example, waiting times. In stage 2, the institutional support was assigned to overwhelmed middle managers who were in charge of several programmes and only able to provide routine administrative supervision. Organisational support for integration including facilita—tion of meetings, development of local guidelines, provi—sion of training, supervision and feedback is associated with better staff engagement, change management and sustainability of the collaborative care.1011Conversely, weak local agreements and inconsistent guidance over time have been identified as barriers to implementa—tion of matrix support in Brazil,38as well as of collabo—rative care in the USA.39Only 22% of PC teams in Brazil reported receiving any management support to imple—ment matrix support.16The broader scope of the matrix support teams in stage 2 (NASF teams) also implied more administrative complexity and competing demands to the PC teams, potentially reducing the opportunities for clinical collaboration between MH and PC teams. This is consistent with a previous study that evaluated the effects of a mental health training intervention in four Brazilian cities and suggested overload of PC teams with competing health problems as a possible explanation for reduced detection and treatment of mental disorders.40

Figure 3 Proportion of each antidepressant class (tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)) prescribed per visit and per year, 2005–2015.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the EMR registry provided no symptoms data; therefore, clinical outcomes were not assessed. However, antidepressant prescriptions have been previously used as a proxy of clinical outcomes in collaborative care for depression.67Second, data on referrals to MH professionals, or concurrent care provided by them, was limited; it was not possible to assess conti—nuity of care. Therefore, we could not compare our find—ings with previous studies that suggest positive effects of matrix support interventions and the NASF programme in process outcomes like quality of referrals and commu—nication between distinct providers.1415Third, the detec—tion measures did not accurately express the incidence or prevalence of mental disorders, but rather estimates of care provision. However, previous research supports the use of a combination of diagnostic codes and antidepres—sant prescriptions as an indicator of access to treatment.29Fourth, the treatment measures did not allow for any assessment of the quality of treatments in terms of dose, duration or patients’ adherence. In addition, there were no EMR data on the prescription of benzodiazepines due to local health legislation that requires such drugs to be prescribed only on paper. This prevented cross— checking of changes in prescription patterns; for example, whether the increased antidepressant prescription was accompa—nied by reduction of benzodiazepines. Fifth, the degree of matrix support implementation possibly varied among the clinics and over time, and an analysis of such varia—tion would add relevant information to the aggregated data; however, such assessment was not possible based on the EMR data and would request other research designs. Sixth, it is possible that some diagnoses and treatments were inaccurately recorded or missing, and that patients who left the cohort during the study may have been systematically different from those who continued to attend primary care, which could have biased results. In particular, changes in the accuracy and complete—ness of recorded diagnoses and treatments would be most likely to have biased our findings if they changed over time. Lastly, this was an observational study, which allows very limited causal inference about the interven—tion, for several reasons. Because EMRs were introduced at the same time as the matrix support intervention, we could not use these data to compare trends in diagnosis and prescribing before and after the intervention was introduced but could only compare two stages of the intervention having different intensities. It is possible that the changes observed during stage 1 might have happened even without the intervention because of other influences. Similarly, the changes in outcomes from stage 1 to stage 2 might also have been caused by other factors, that is, by unmeasured time— varying confounding variables. The only potential confounders that we were able to control for were age and sex, and it is possible that other unmeasured variables such as socioeconomic factors or comorbidities might have confounded our results, especially if these changed over time. Differences in the characteristics of the health centres included in the study might also have biased the results. However, a huge dataset of routine medical care was interrogated, which showed temporal trends consistent with the aims of the intervention, thereby providing a basis for effectiveness studies.

Implications for practice and research

The positive outcomes of stage 1 suggest that the matrix support intervention may increase access to treatments when implemented with adequate on— site support to clinical integration. In this study’s setting, the support to integration was provided by one full— time mental health worker for 50 PC practices, what is likely to be feasible in other primary care settings. The inconsistent results of stage 2 stress the need for a better understanding of how this programme is affected by variations in administra—tive support and by competing demands to the primary care teams. These conditions are the rule in real— world primary care settings in which several programmes need to converge to provide patient— centred care and deal with multi— comorbidity. In particular, there is a need to better understand the specific contribution of supportive strategies, for example, on— site supervision; intervention components, for example, regular meetings; and other contextual factors, for example, competing programmes and lack of time of the PC teams to the matrix support outcomes. The use of routinely collected data to evaluate such experiences should be improved and encouraged, including the assessment of non— pharmacological compo—nents, for example, psychological therapies, and system— level effects, for example, continuity of care. Future research should use experimental or quasi— experimental designs to assess clinical outcomes of the matrix support (eg, depression symptoms) across sites with distinct levels and modalities of matrix support, for example, mental health— only versus broader multi— professional teams; and across distinct groups of disorders like psychotic and common mental disorders.

CONCLUSION

This was the first study to show a positive association between implementation of the matrix support interven—tion and improved detection and treatment of mental disorders in primary care, in particular anxiety and depressive disorders. Our findings suggest that the effects of matrix support in mental health care may be favoured by on— site organisational support to the clinical integra—tion between MH and PC workers. Conversely, competing demands to PCPs and reduced opportunities for clinical integration may reduce the effects of matrix support in mental health treatment provision.

TwitterSonia Saraiva @SoniaSaraiva

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to all health professionals of the Municipal Secretary of Health of Florianópolis who contributed to the development of the matrix support intervention described in this study and to the managers who supported its implementation.

ContributorsSS conceived and designed the study and wrote the first draft of the paper. MB analysed the data. MA extracted the data from the institutional database. AL contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors contributed intellectual content, edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

FundingThe authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for- profit sectors.

Competing interestsSS is an ex- employee of the Municipal Secretary of Health of Florianópolis, Brazil.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Ethics approvalThe study was approved by the Research Committee of the Municipal Secretary of Health of Florianópolis and by the Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee (reference number 25748313.7.0000.0118).

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementData may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The secondary and anonymised data used in this study were extracted from the electronic medical records database of the host institution and consisted of demographic information, diagnoses and drug prescriptions routinely recorded by doctors in the electronic medical registry of Florianópolis, Brazil. The authors obtained authorisation of its use only for the purposes of this study. The data may be available on request for use in other studies from the Municipal Secretary of Health of Florianópolis, Brazil ( gabinetesmsfpolis@ gmail. com).

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

ORCID iDSonia Saraiva http:// orcid. org/ 0000- 0002- 2305- 9246

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Perceived barriers and primary care access experiences among immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada

- The process of transprofessional collaboration: how caregivers integrated the perspectives of rehabilitation through working with a physical therapist

- Reformulation and strengthening of return- of- service (ROS) schemes could change the narrative on global health workforce distribution and shortages in sub- Saharan Africa

- New hypertension and diabetes diagnoses following the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion

- How well did Norwegian general practice prepare to address the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Family medicine residency training in Ghana after 20 years: resident attitudes about their education