Perceived barriers and primary care access experiences among immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada

Tanvir C Turin, Ruksana Rashid, Mahzabin Ferdous, Iffat Naeem, Nahid Rumana, Afsana Rahman, Nafiza Rahman, Mohammad Lasker

ABSTRACT

Objective The study aimed to explore the experience of male members of a rapidly grown community of Bangladeshi immigrants while accessing primary healthcare (PHC) services in Canada.

Design A qualitative research was conducted among a sample of Bangladeshi immigrant men through a community- based participatory research approach. Focus group discussions were conducted to collect the qualitative data where thematic analysis was applied.

Setting The focus group discussions were held in various community centres such as individual meeting rooms at public libraries, community halls and so on arranged in collaboration with community organisations while ensuring complete privacy.

Participant Thirty- eight adults, Bangladeshi immigrant men, living in Calgary were selected for this study and participated in six different focus groups. The sample represents mostly married, educated, Muslim, Bangla speaking, aged over 25 years, full- time or self- employed and living in an urban centre in Canada >5 years.

Result The focus groups have highlighted long wait time as an important barrier. Long wait at the emergency room, difficulties to get access to general physicians when feeling sick, slow referral process and long wait at the clinic even after making an appointment impact their daily chores, work and access to care. Language is another important barrier that impedes effective communication between physicians and immigrant patients, thus the quality of care. Unfamiliarity with the healthcare system and lack of resources were also voiced that hinder access to healthcare for immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada. However, no gender- specific barriers unique to men have been identified in this study.

Conclusion The barriers to accessing PHC services for Bangladeshi immigrant men are similar to that of other visible minority immigrants. It is important to recognise the extent of barriers across various immigrant groups to effectively shape public policy and improve access to PHC.

INTRODUCTION

Easy and timely access to healthcare services is a fundamental concern for the health of Canadians.12Primary healthcare (PHC) services are the first point of contact with healthcare when Canadians are in need, providing increasingly comprehensive services like prevention, treatment of common diseases and injuries, basic emergency services, referrals to and coordination with other levels of care (eg, hospital and specialist care, primary mental healthcare, palliative and end- of- life care), health promotion, healthy child development, primary maternity care and rehabilitation services.3Canada provides publicly funded healthcare that ensures all Canadian residents have access to necessary hospital and physician services without paying out of pocket.4

Regardless of publicly covered healthcare services, immigrants continue to face significant difficulties when seeking healthcare in Canada.56Studies show that the health status of immigrants who have lived in Canada for 10 years or more to be worse than those of recent immigrants,78despite arriving with similar or better self- reported health than the general Canadian population, a phenomenon described as the ‘healthy immigrant effect’, indicating worsening immigrant health status over time.9With over one- fifth of the Canadian population being foreign born,10this lack of equitable healthcare access is an important issue for the healthcare system.9Researchers have reported a number of causal factors for this quick deterioration of immigrant health. These include acculturation of the new immigrants or adoption of Canadian lifestyle,11environmental factors,12postmigration stress13and discrimination.14

Gender differences in disease distribution have been well noted and show that certain chronic conditions may be higher for men. Indeed, studies analysing the National Population Health Survey have found that immigrant men report a higher number of unmet healthcare needs as compared with women.15These differences have been attributed to intersections between genetic predispositions, cultural background, spiritual beliefs and racialised masculinity.16The results are predominant health behaviours linked to men, which include the adoption of high- risk activities, denial of illness, under- utilisation of healthcare services and poor uptake of health promotion programmes. In this case, immigrant health offers a layer of complexity, where gender- cultural- sensitive healthcare is needed to approach problems of access to primary care.17Gender and cultural factors affect both the development of health problems (such as genital mutilation in certain ethnic groups) and the use of health services (men use less healthcare services than women).1819The utilisation of healthcare resources is needed to be targeted to facilitate uptake of healthcare services by both men and women equally from different sociocultural groups.18Spending more time and putting more effort into the consideration of immigrant men’s sociocultural perspective, including the differences within various immigrant communities, may potentially improve the gender and cultural sensitivity of the healthcare.17

While there is a reasonable number of studies describing the barriers faced by immigrants while accessing healthcare,52021research lacks a focus on immigrant men and their nuanced views, attitudes and experiences with PHC services.5To fill this gap, the aim of this study is to explore the experience of Bangladeshi immigrant men while accessing PHC services in Canada by means of community- based focus group discussions (FGDs). Bangladeshi- Canadians are part of the rapidly growing South Asian community in Canada, with an increased rate of 110% from 2001 to 2011.22Bangladeshi- Canadian immigrants have been studied regarding barriers to access healthcare as a part of greater South Asian communities, however, Each South Asian community is remarkably different from each other in their sociocultural and religious nuances, and Bangladeshi community is no different.23It has been postulated that Bangladeshi- Canadian immigrants are often lost in the shadow of other bigger South Asian communities.24This is reflected in the literature as well where there are only a handful of studies on Bangladeshi immigrants in Canada and globally. However, none of the studies captured specifically Bangladeshi men’s perspective with respect to accessing healthcare in the host countries.

METHODS

Optimal access to care is not established only by the existence of the service but also it is accomplished when the services are utilisable by all consumers irrespective of their sociocultural background, gender identity and economic status. Immigrant health and access to care may differ based on sociocultural beliefs, individual health behaviour, desire and need of services and delivery of the services in terms of time, place and provider of the services.16While research exploring healthcare issues is abundant focusing on broad ethnocultural communities (eg, South Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, etc) in Canada, little research has been done on country or language- based small immigrant groups such as Bangladeshi immigrant community. To explore the attitudes and perceptions of immigrant men regarding the healthcare system and health services, we applied the focus group technique.2526Perceived barriers to healthcare may differ from immigrant men to immigrant women as well as one immigrant population group to another depending on their sociocultural nuances and the interaction of that background with the culture of their host country. While such complex scenario may blind the researchers and policymakers to foresee the unique experiences of each immigrant population group and subgroup (ie, women, men, youth, elderly or other group based on gender/sexual identity, chronic diseases, etc), the group interaction of the focus groups may reveal those key perspective and hidden nuances.27Moreover, to engage the Bangladeshi immigrant community, community- based participatory research (CBPR) or integrated knowledge translation (iKT) approach was used in this study. CBPR or iKT are collaborative research approaches that equitably involves community members, organisational representatives and academic researchers in all aspects of the process, enabling all partners to contribute their expertise and share responsibility.2829These approaches bring the researchers close to the community that facilitates them to be open to the ‘outsider’ researchers, thus help researchers identify and resolve the health and wellness disparities in the community.30

In the community engagement phase of our programme of research, we conducted a number of informal conversations with Bangladeshi- Canadian community members. This research question was one of the derivatives of those consultations. We also had Bangladeshi- Canadian community- based citizen researchers as members of our research team (NR, AR and ML). They have been involved in community engagement, participant recruitment, transcription and translation process related to our study. They were also engaged during the analysis process to contextualise the codes and themes arising from the FGDs as well as writing manuscript. We also discussed the study codes and themes during our paper writing phase with three FGD participants who agreed to be contacted for this purpose.

We conducted six FGDs in Calgary among 38 Bangladeshi immigrant men; each FGD consisted of four to eightparticipants. The FGDs were conducted between July and December 2018 in community organisations, considering the convenience and accessibility of the participants. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

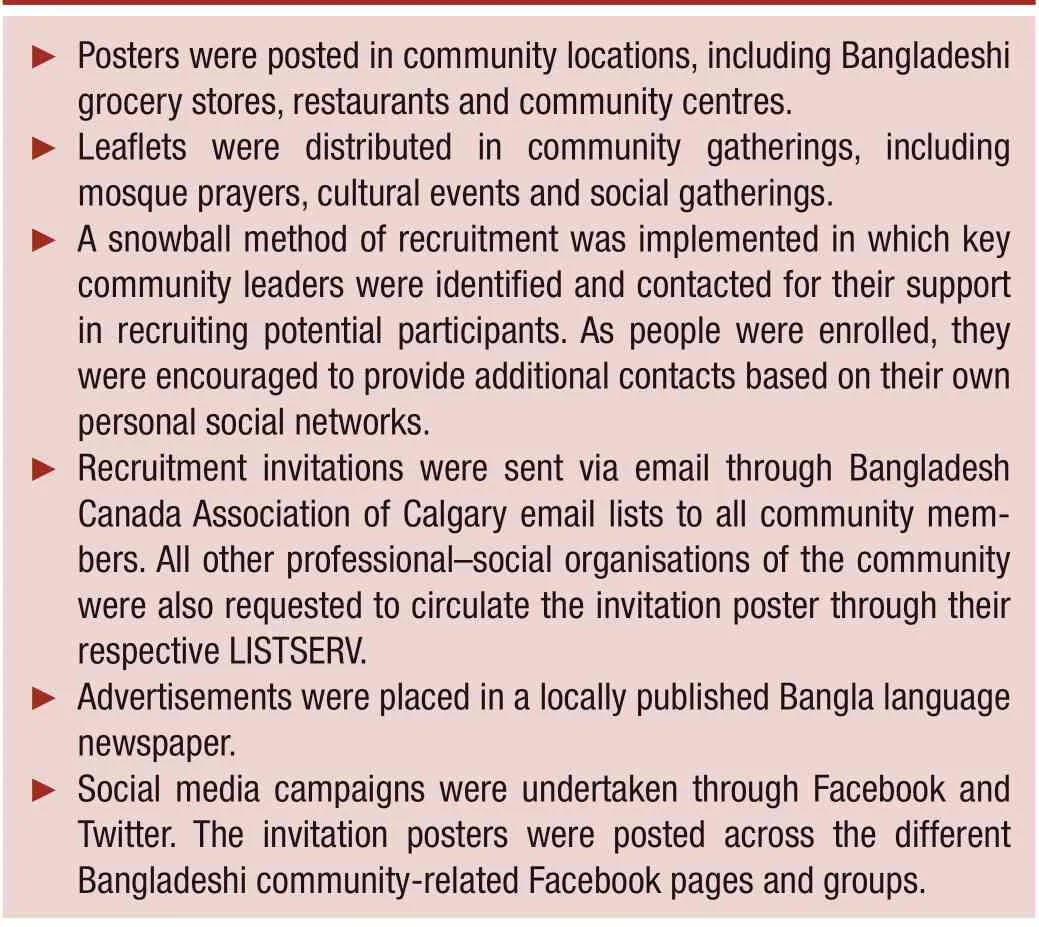

Box 1 Participant recruitment strategies

Recruitment and participants

To facilitate free discussion and ensure the FGDs encompassed a diverse set of perspectives, FGD participants were chosen carefully according to prespecified selection criteria; the participant (a) will be an adult first- generation legal Bangladeshi immigrant man and (b) must have exposure to Canadian healthcare. Based on the selection criteria and considering the distribution of the Bangladeshi immigrant population in Calgary, recruitment strategies (box 1) were formulated with feedback from community leaders and our citizen researchers.

Potential participants were contacted by the study coordinator and were informed about the study objective, either by telephone, by mail (first contact) or in person (onsite). Participants were assured of their privacy, anonymity and right to withdraw at any point.

Conducting FGDs

FGDs were held in community centres such as (individual meeting rooms at the public library, community halls etc) arranged in help with community organisations. The FGDs were conducted by a moderator and a note taker, both of whom were bilingual. Although the discussions were conducted in Bangla, the participants were given the option of using either Bangla or English. Each FGD started with the explanation and signature of the written consent form. The moderator did not act as an expert but stimulated and supported discussions as per FGD guide. The moderator applied the appropriate working group techniques and provided equal opportunities for communication to all participants. FGDs were audiorecorded with the participants’ consent and lasted for about 1.5–2 hours.

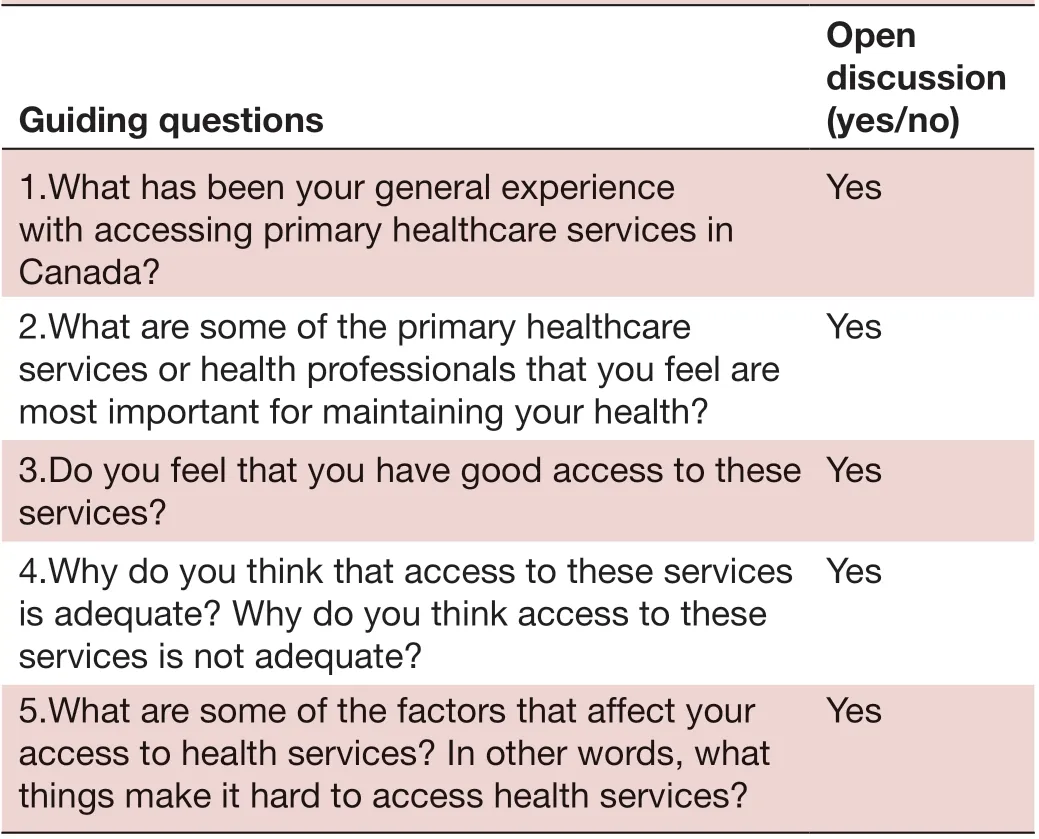

Table 1 Guiding questions for the focus group discussions for identifying and prioritising barriers to primary healthcare recipients

The guiding questions for the FGDs are provided in table 1. The discussions started with these questions, however, the moderator occasionally posed further open- ended questions to clarify content or context, to deepen the perspectives voiced and to stimulate the flow of discussion if participants’ statements were unclear or if the discussion came to a halt. The assistant moderator acted as a note taker and was responsible for taking field notes that included capturing what was said and expressed, noting the tone of the discussion, the order in which people spoke (by participant number), phrases or statements made by each participant and non- verbal expressions. At the end of each discussion, the assistant moderator summarised the discussion to the participants and asked for their feedback and validation of the collected data. These summaries as well as the field notes were used to gauge saturation in the discussion points the participants were sharing. At the end of the sixth FGD, the research team felt that theme saturation had been met, so the recruitment was halted. The final decision of not conducting any more FGDs was made once the transcriptions of all the FGDs were reviewed to verify that the saturation point had been reached.

Analysis

Data analysis was then undertaken using the six phases of thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke,31which includes the following:

Familiarising oneself with the data

All recorded FGDs were transcribed verbatim and the complete transcript was compared with the recorded audio and the handwritten notes taken by the note taker to fill in the gaps. The transcription and analysis were done manually without use of any instrument. The transcripts were read multiple times searching for meanings and patterns to code.

Generating initial codes

The data from the first three FGDs were coded independently in English by two bilingual researchers (the RA and PI), and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The remaining FGDs were coded by the RA, with random checking by the PI. The two coders took the necessary steps to ensure the accuracy of the translation.32

Searching for themes

In this stage, codes were extracted into Microsoft Excel files (one file per interview). After analysing the codes, relevant codes were collected into potential themes and sub- themes and all relevant data gathered into each potential theme and sub- themes.

Reviewing themes

In this stage, the themes and sub- themes were tested in relation to the coded extracts and the entire data set, generating a thematic map of the analysis.

Defining and naming themes

In this stage of ongoing analysis, the specifics of each theme, sub- themes and the overall story of the analysis were refined, generating clear definitions and names for each theme and sub- theme.

Producing the report

The trusting relationship built up between the participants and the researchers through the engagement with the community ensured the credibility of the results of this study. The research team, including the principal investigator and first author of this manuscript, mostly comprised of researchers from a similar ethnic background (ie, immigrants, Bangladeshi and Bangla speaking) that largely contributed to connecting with the participants at a personal and emotional level and help them share their thoughts and experiences to the research team. Moreover, the principal investigator’s primary research interests include understanding the health and wellness challenges of ethnic, immigrant and refugee populations. These experiences and knowledge of the principal investigator and the research team with immigrants’ health choices and healthcare access in Canada helped the fitting interpretation of the research findings by relating them with the particular social, cultural and relational contexts. The citizen researchers of the team were also essential in conduction of the FGDs and triangulating the research findings with their share of personal experience as immigrants as well as their community engagement experience. Finally, participants’ perceptions and views recorded by the research team were member- checked by a representative sample of participants to ensure their accuracy and completeness.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of the participants

RESULT

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. They were predominantly educated and in the age range of over the age of 46–55 years. The majority of the participants was married, Muslim and Bangla speaking men. Most of the participants were employed either full time or were self- employed. Over half of the participants migrated to Canada 5–19 years ago.

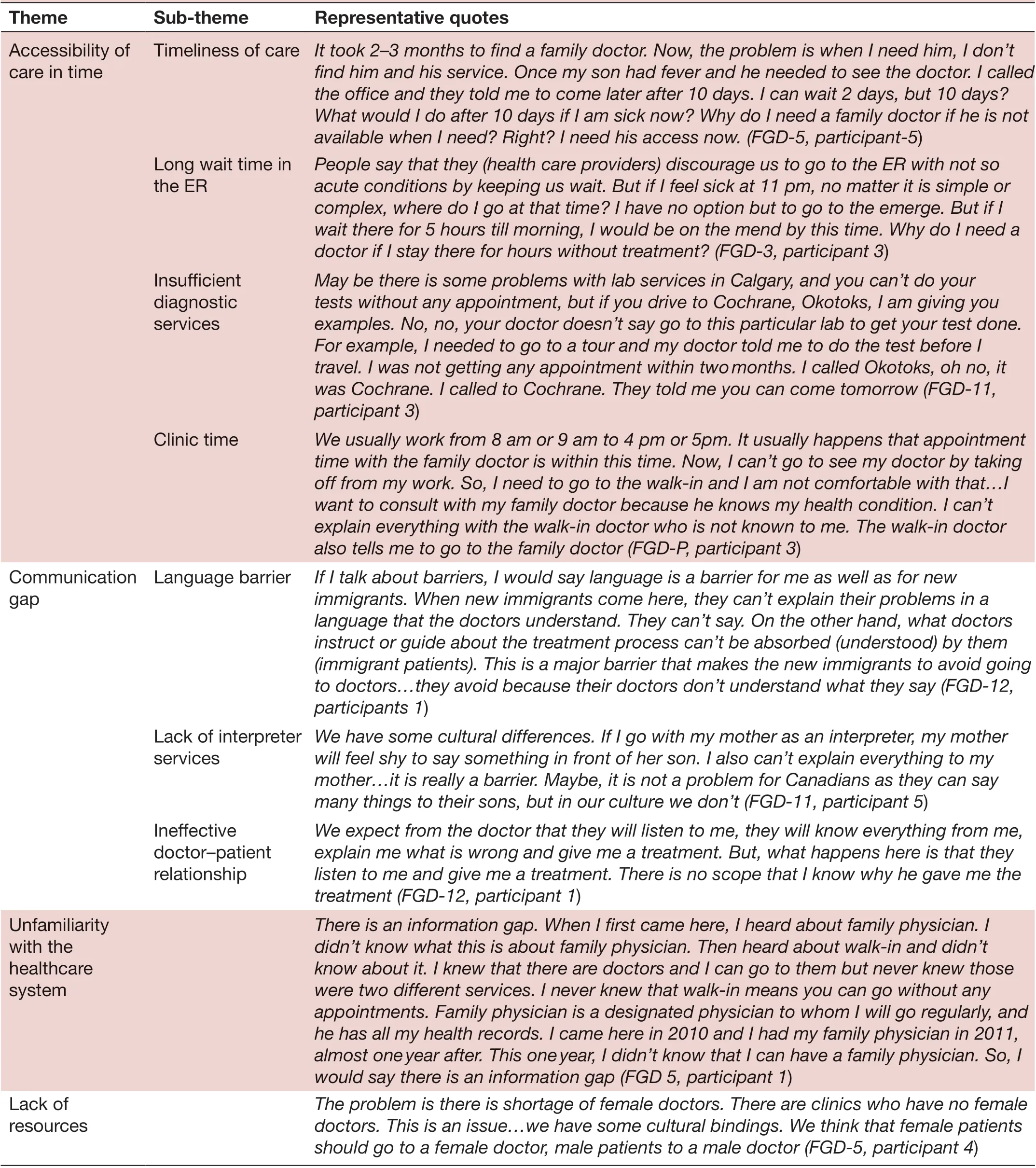

The inductive thematic analysis of the findings of these FGDs revealed the following four themes: Accessibility of Care in Time, Communication Gap, Unfamiliarity with the healthcare System and Lack of Resources. The first theme, Accessibility of Care in Time, provides a glimpse into participants’ frustration and suffering from long wait time accessing care in the emergency room (ER), at the doctor’s clinic, and to get an appointment from doctors and diagnostic services. The second major theme, Communication Gap, explains how language barriers and ineffective communication between physicians and immigrant patients influence their access and quality of care. The third theme, Unfamiliarity with the Health Care System, examines the barriers participants experienced because of the lack of information about available resources, care and how the system works. The final theme, Lack of Resources, highlights participants’ perception of lack of resources of healthcare systems impacting their access to healthcare services. Representative quotes from each of the main themes and sub- themes arising from the FGDs are set out in table 3.

Accessibility of care in time

Accessibility to primary care services in a short time was found to be an important aspect related to the barrier of accessing primary care in this study. This was originated from either one of the following issues.

Timeliness of care

A family physician is usually the first contact in primary care in Canada. Participants often negatively perceived that the appointment system with family physicians restricted their access to care in time. It was voiced in all the FGDs that they could not make appointments with their family physicians when their help was immediately needed. However, differences in opinion were also noted as only a couple of participants accepted that family doctors were for less acute and regular healthcare services, such as follow- ups and yearly check- ups. Therefore, individuals who need urgent help could visit the ER or walk- in clinics depending on the severity of their concerns.

Long wait time in the ER

Most of the participants felt that a long wait in the ER was not necessary and intensified the patient’s suffering and frustration as well as might disrupt the daily activities of a family and cause financial loss. However, a few participants disagreed and told that patients are treated in the ER on priority based, and no serious patients received delayed treatment in their experience. Wait time may also be influenced by the language barrier of the patient or accompanying family members.

Insufficient diagnostic services

Long wait time to get an appointment for diagnostic tests, such as a colonoscopy or mammography, was highlighted as another reason why participants had trouble accessing both primary and specialist healthcare services. Nevertheless, this delay could be shortened by travelling to other communities pointed out by a couple of participants.

Clinic time

The analysis of the FGD data of this study also revealed that overlapping of the clinic time with work hours and a lack of after- hours services largely impede accessing care in time. Therefore, patients needed to visit the ER for less critical but somewhat distressing conditions

Communication gap

Data analysis of the FGDs in this study revealed that the ability to articulate a health issue in one of Canada’s official languages (English or French), the ability to use appropriate communication styles and an effective doctor–patient relationship was important to navigating care and available resources.

Language barrier

The analysis of the FGD data revealed that the language difference is one of the most dominant barriers to accessing and navigating primary care services. The language barrier hinders patients to express their health issues to doctors as well as doctors to provide instructions for the prescribed medicines, follow- up instructions and other advice. This ultimately impacts the treatment process and patient satisfaction and results in under- utilisation of the available healthcare services. Lack of medical vocabulary and cultural differences further impeded effective communication.

Lack of interpreter services

The analysis of the data of this study also found that there was a perceived lack of interpreter services in PHC services. Participants implied that sufficient professional interpreter service instead of using family members as an interpreter could improve the communication gap between physicians and patients for whom English was not the primary language.

Ineffective doctor—patient relationship

A number of participants emphasised the importance of appropriate communication between healthcare providers and patients to build confidence for patients and a good doctor–patient relationship. A lack of proper examination, explanation of treatment plan, side- effects of the prescribed medication or complications and a lack of compassion from the doctors were mentioned. Participants also claimed that doctors sometimes did not offer enough time to listen to patients, and therefore they felt pressure to discuss their health issues hurriedly in the second language.

Table 3 Themes arising from Focus Group Discussions with Bangladeshi Canadian immigrant men regarding healthcare access

UNFAMILIARITY WITH THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Participants of the study discussed that unfamiliarity with the Canadian healthcare system structure and lack of information on available resources negatively impacted access to healthcare. For example, some participants mentioned that they did not know that unlike home country, people in Canada are supposed to have a family physician and visit them when they are sick. However, they also did not know about walk- in clinics where one can visit doctors without prior appointments, which is rather more similar to the healthcare system of their home country (table 3).

PERCEPTION OF LACK OF RESOURCES

Data analysis of the FGDs of the study further revealed that access to care was largely influenced by the availability of resources. Participants stated that the number of clinics, especially after- hours and urgent care clinics, were not sufficient to provide care. They also discussed the lack of hospital resources and mentioned that patients were discharged only a few hours after surgery or delivery, leaving the patient suffering.

Participants also identified that there were insufficient physicians proportionate to the population size. They also mentioned that the unavailability of physicians negatively impacted access to and utilisation of primary care. Physicians from different ethnic groups could also improve access to care for many immigrants.

DISCUSSION

This study attempts to start filling the gap in the literature on a particularly visible minority group in Canada with a gender- focused view in terms of healthcare access barriers. Previously unexplored perspectives of immigrant men regarding barriers to access PHC services were investigated in the study through FGDs. Bangladeshi- Canadian immigrant men reported unavailability of care in time, communication barrier, unfamiliarity with the healthcare system and lack of resources as their common barriers. Long wait time and communication difficulty were commonly voiced by the participants across the FGDs. However, all these four types of barriers might be deemed to be interconnected to each other. For instance, overlapping of clinic time with work hours and lack of resources (eg, lack of a sufficient number of family physicians, unavailability of urgent- care options, walk- in clinics etc) largely contributed to the crowding in ER and further increased the wait time. And, in turn, accessibility of care was hindered. Moreover, the language barrier demands interpreter services, and a lack of interpreter services (lack of resources) has hampered accessibility of care.

Long wait time for specialised services, non- emergency surgery and selected diagnostic tests were also reported to be the biggest barrier to accessing PHC by the overall Canadian population,12making it a general concern for all Canadians. Dissatisfaction with walk- in clinic services due to longer wait time, unfamiliarity and lack of continuity of care was also noted by the general Canadian population.33However, in our study sample, we also observed some level of acceptance regarding the unavailability of care in time, indicating that during acute illness, people can avoid long wait time from their family physicians by going to a walk- in clinic; long wait time in the ER is reasonable for non- urgent patients, and wait time in diagnostic centres is avoidable if someone is willing to travel to surrounding rural area centres or a less densely populated area. The discrepancy in opinions of the participants may reflect the fact that many immigrants, especially more recent immigrants, are not well aware of the Canadian health system and culture, leading to an expectation–reality mismatch and overall dissatisfaction. A lack of information about the Canadian healthcare system that was voiced by the FGD participants of the study may further contribute to this.

When approaching healthcare services, the language barrier has been reported to be a global encounter for immigrants.52134–38Likewise, our study participants frequently struggled with explaining their problems and understanding instructions from physicians due to a lack of fluency in one of Canada’s official languages and a lack of knowledge about medical terminology. Less time spent by physicians explaining their condition, medication and prognosis also created frustrations among participants. The use of interpreter services has previously shown some positive results in improving communication gaps among immigrants,39however, the participants of this study reported a lack of adequately trained medical interpreter services that was also a major challenge for immigrant and ethnic populations outside Canada.40This may be attributed to the perceived lack of resources (eg, lack of interpreter services, insufficient after- hours clinics, shortage of hospital resources, inadequate ethnic representations among physicians etc) that were also mentioned by the participants of this study as well as in previous studies.41–44

Previous studies showed that immigrant men tend to show reluctance in accessing health services due to sociocultural values.4546Men in many immigrant communities think it is a masculine feature not to access healthcare services when sick.46Moreover, despite social support is positively related to better health, men tend to seek social and peer support less commonly than women.47Reasons may include that men are less likely to share confidential information with others and they receive less health- related and mental support from their friends and others.48However, our study did not reveal any barriers that are relatable particularly to men. Interestingly though, it was mentioned that they would prefer a female provider for their female members of the family, but no preference of gender of providers for themselves was expressed. Gender preference by female patients has widely been reported, especially among South Asian immigrant women.549The findings of our study indicate that the observed gender preference for female healthcare providers by the immigrant women might have been influenced by their ethnocultural customs; where male members of their family are concerned about their female counterparts being exposed to male healthcare providers while not being apprehensive about the gender of provider for their own healthcare.

A strength of the study is our approach of community- engaged programme of research.50Also, we had citizen researchers involved in the research process. These resulted in a friendly and comfortable atmosphere for the participants to talk freely. Thus, the group discussions, being informal with occasional jokes and laughter, gave room to the participants to open up and express their feelings, concerns and understanding freely. The frank environment also led the shy participants to come out of their shell and share their experiences. We collaborated with the community leaders and community organisations during the recruitment process and approached participants through them. This increased the credibility of the research and improved trust between the researchers and the community. Also, the bilingual capability of the research team was an added asset for the work with the Bangladeshi- Canadian grassroots community. As a result, the participants felt engaged and showed interest in further implications. We believe that this approach has laid the first stone of future research collaboration with the community to identify ways of improving access to PHC and will help guide future policy initiatives to improve patients’ experiences in obtaining PHC services in Canada.

A limitation of the study is the susceptibility of the FGDs to bias. In FGDs, group and individual opinions can be influenced by more dominant participants.26However, our FGDs were conducted in a structured way to minimise dominance bias and shyness bias by providing each participant a time slot in which to speak, so they did not have to compete for the floor or attempt to gain the attention of the moderator. We also used snowball sampling for our study, which may lead to selection bias, but, again, this is an effective and efficient strategy for recruiting hard- to- reach minority groups like the one in this study.51The fact that our study population was limited to Bangladeshi immigrant men needs to be kept in mind as they may not be representative of other immigrant populations in Canada. Within the Bangladeshi- Canadian diaspora, the study sample predominantly represents married, educated, Muslim, Bangla speaking men over the age of 25 living in an urban centre. This sample characteristic is not surprising due to the immigration criteria under which a substantial number of Bangladeshi immigrants migrated to Canada. The point- based immigration criteria favoured migrants who are educated, married and had work experience.52–54

Despite the limitations, our study provides valuable insights into potential barriers encountered by this particular group of immigrants to PHC services in Canada. The findings of the study reverberate those of other visible minority study findings while laying the groundwork for further gender- focused and community- focused studies that are warranted to see the complete picture and find any disparities between different groups of immigrant populations. It builds on existing knowledge to illustrate the various nuances expressed by this group of immigrants and highlights the value of qualitative research to adequately document and contextualise specific concerns on this critical issue. More similar qualitative studies focusing on a certain group of immigrants are needed particularly to identify ways to address these barriers because different groups of immigrant men and women might need to be approached in different ways. For example, from a health system perspective, arranging interpreter services for a patient belonging to a smaller ethno- cultural community (language) may not be as feasible as arranging service for a patient belonging to a larger ethno- cultural community. Using remote telephone or video interpretation may resolve this barrier, however, these facilities are still developing, have their own limitations, and often underutilised at current healthcare settings.55

CONCLUSION

This study attempted to capture the perspective of Bangladeshi immigrant men, an understudied group of visible minority immigrants in Canada, in terms of barriers to accessing PHC services. Information concerning patients’ experiences in accessing healthcare services is needed to provide a more comprehensive picture regarding access to care. In this era of global migration, the healthcare needs and issues of various immigrant communities need to be evaluated and addressed. This contributes towards the concept of precision population health; one size fits all types of community health, and well- being approach will not be appropriate.

TwitterTanvir C Turin @drturin

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge the engagement and support we have received from the Bangladeshi- Canadian grassroots community members in Calgary. Also, we appreciate the encouragement we have received from all the socio- cultural organisations belonging to this community including the leadership of Bangladesh Canada Association of Calgary.

ContributorsTCT, NR and ML conceived research study and designed the methods for the study. ML, NR and TCT conducted initial community engagement and mobilisation initiatives for participant recruitment and facilitated the arrangements of the focus group discussions. RR and MF conducted the focus group discussions and compiled the field notes. AR transcribed and translated the focus group discussions. RR and TCT analysed and interpreted the data. ML, NR, AR and NR helped contextualisation of the interpretation by employing the ethno- cultural lens. TCT, IN, RR and MF drafted the manuscript. ML, NR, AR and NR critically appraised the draft for intellectual contribution.

FundingThis research was supported by the funding from Canadian Institute of Health Research (201612PEG-384033), Department of Family Medicine in University of Calgary, and Alberta Health Services.

Competing interestsNone declared.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Ethics approvalThe study was reviewed and approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of University of Calgary before commencing any research activity (Ethics ID: REB15-2325).

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementNo data are available.

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- The process of transprofessional collaboration: how caregivers integrated the perspectives of rehabilitation through working with a physical therapist

- Reformulation and strengthening of return- of- service (ROS) schemes could change the narrative on global health workforce distribution and shortages in sub- Saharan Africa

- New hypertension and diabetes diagnoses following the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion

- How well did Norwegian general practice prepare to address the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Family medicine residency training in Ghana after 20 years: resident attitudes about their education

- Exploring the structure of social media application- based information- sharing clinical networks in a community in Japan using a social network analysis approach