Incidence and mortality of female breast cancer in the Asia-Paci fi c region

Danny R. Youlden, Susanna M. Cramb,2, Cheng Har Yip, Peter D. Baade,4,5

1Cancer Council Queensland, Brisbane 4006, Australia;

2School of Mathematical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane 4000, Australia;

3Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia;

4Grif fi th Health Institute, Grif fi th University, Gold Coast 4222, Australia;

5School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane 4000, Australia

Incidence and mortality of female breast cancer in the Asia-Paci fi c region

Danny R. Youlden1, Susanna M. Cramb1,2, Cheng Har Yip3, Peter D. Baade1,4,5

1Cancer Council Queensland, Brisbane 4006, Australia;

2School of Mathematical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane 4000, Australia;

3Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia;

4Grif fi th Health Institute, Grif fi th University, Gold Coast 4222, Australia;

5School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane 4000, Australia

Objective: To provide an overview of the incidence and mortality of female breast cancer for countries in the Asia-Paci fi c region.

Asia-Paci fi c region; female breast cancer; epidemiology; incidence; mortality

Introduction

Until recently, information on the epidemiology of female breast cancer was mainly gleaned from studies conducted in the Western world1,2. In 1990, it was estimated that 59% of breast cancer cases occurred in more developed countries (de fi ned as North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Japan), although these areas accounted for less than a quarter of theglobal female population at the time3. The situation changed considerably over the next two decades; by 2008, the total number of new diagnoses were evenly divided between more developed and less developed countries4,5, and by 2012 it was estimated that the majority (53%) of cases of female breast cancer were occurring in less developed countries6. While incidence rates still remain much higher in more developed countries, this shiin the global distribution of cases highlights that breast cancer is continuing to emerge as a major health issue for women in Asia, Africa and South America.

The Asia-Pacific region includes Eastern and South-Eastern Asia as well as Oceania (see Table 1 for a full list of the countries included)6. It comprises a diverse mix of geography, cultures and economies1, and is home to almost a third (32%) of the global

female population7.is region is of speci fi c interest because the annual increases in female breast cancer incidence since 1990 in some parts of the Asia-Paci fi c have been reported to be up to eight times higher than the world average8,9.

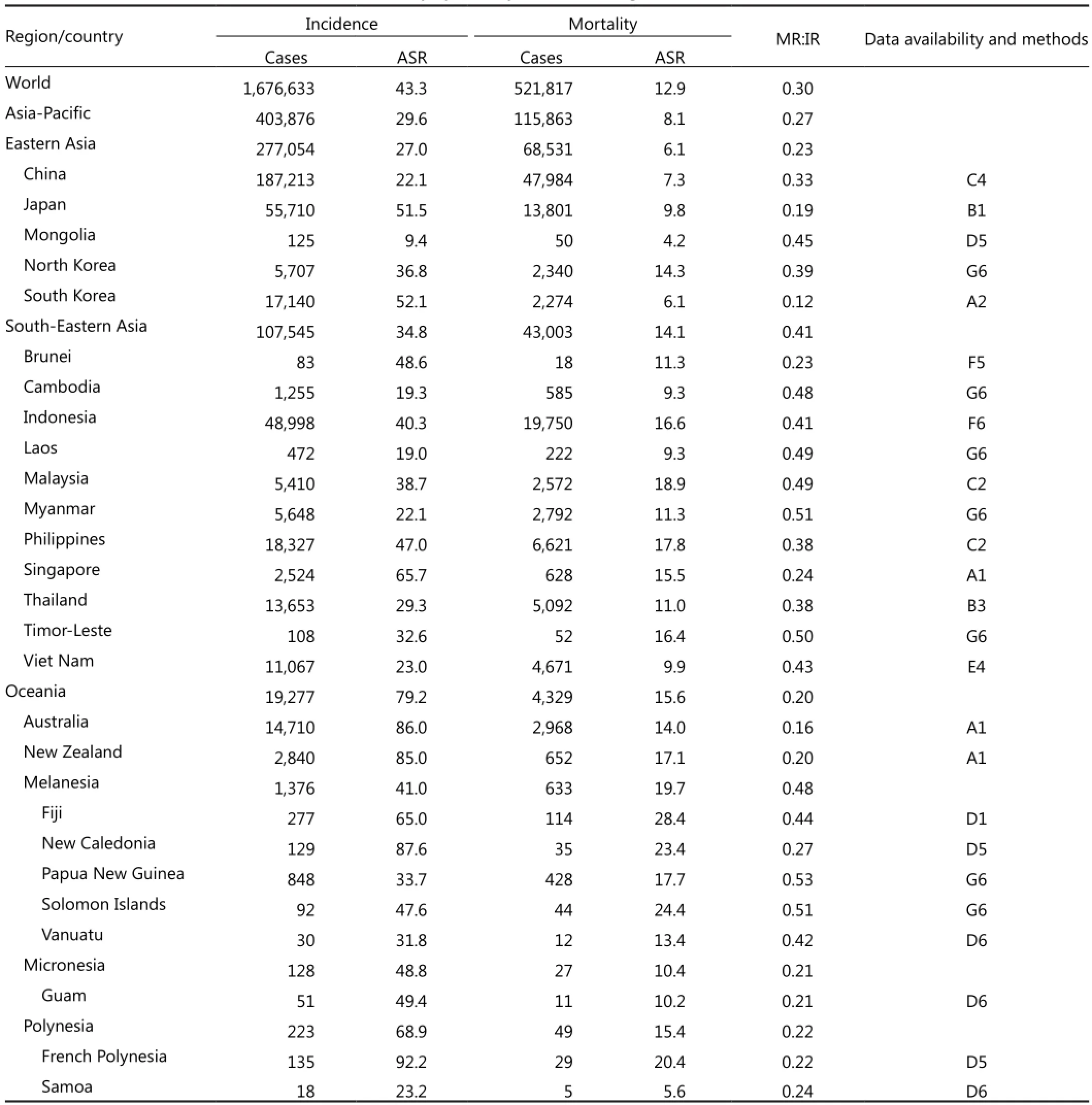

Table 1 Estimated breast cancer incidence and mortality by country, Asia-Paci fi c region, 2012

The purpose of this study was to describe and compare the latest available incidence and mortality data on female breast cancer for countries within the Asia-Pacific region. This is important in terms of monitoring changes in the burden of breast cancer over time and to allow some degree of benchmarking between countries, thus identifying where action is most required to prevent breast cancer and to improve outcomes for women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Data

Incidence and mortality estimates for the year 2012 were extracted from the GLOBOCAN database compiled by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)6. The latest estimates available by age at diagnosis (under 50 vs. 50 years and older) were for 200810. Data on incidence by stage at diagnosis were sourced from individual publications. Only cases of primary invasive breast cancer (ICD-10/ICD-O-3: C50 or ICD-9: B113) were included, unless otherwise speci fi ed.

Since GLOBOCAN data are for a single year, we also obtained longitudinal incidence data for trend analyses from IARC11and/ or individual cancer registries12-16where available. Potential cancer registries were identified through online searches. Data was either downloaded directly from the website, or Registrars were contacted when data was unavailable online. Table 2 lists the countries for which incidence trend data were obtained.

Mortality trend analyses used data from the World Health Organisation (WHO) Mortality Database18, which contains cause of death by age, sex and year as reported by individual countries. Countries within the Asia-Pacific region were included if they were in the WHO Mortality Database, had at least ten years of data available during 1980-2011, and an annual average of at least 100 deaths/year due to breast cancer during the most recent five years. Eligible countries for the mortality trend analyses are listed in Table 3.e criteria resulted in the exclusion of Brunei, Fiji, Kiribati, and Papua New Guinea. Several other countries, including Indonesia, North Korea, Viet Nam and Cambodia were not listed in the WHO Mortality Database.

Statistical analysis

All incidence and mortality rates were directly age-standardised to the Segi World Standard population17. Rates were expressed per 100,000 female population, and were estimated for all ages combined, as well as being stratified into two broad age groups that approximate pre-menopausal (under 50 years old at diagnosis) and post-menopausal (50 years and over) women. Calculations were performed in Stata v12.0 (StataCorp, Texas, United States) and maps were generated in Manifold System v8.0 (Manifold Soware Limited, Wanchai, Hong Kong).

Recent survival estimates based on a consistent methodology were not available for most countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Instead, the mortality to incidence rate ratio (MR:IR) was used to provide an approximation for the prospects of survival in each country. The MR:IR has a range between 0 and 1; lower values of MR:IR (closer to zero) denote higher rates of survival, while higher values of MR:IR (closer to one) indicate poorer survival.

Trends in incidence and mortality rates were analysed using the Joinpoint regression program v4.0.4 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda). This method evaluates changing linear trends across consecutive time periods19. A ‘joinpoint’ occurs when the linear trend changes significantly in either direction or magnitude. All of the models were run under the same specifications, namely that a minimum of 6 years was required between a joinpoint and either end of the data series or at least 4 years of data between joinpoints, with a maximum of three joinpoints allowed. Trends were reported in terms of the annual percent change (APC).

Results

Incidence rates

It was estimated that almost 1.7 million cases of female breast cancer were diagnosed worldwide during 2012, corresponding to a rate of 43 per 100,000 (Table 1). Close to a quarter (24%) of all breast cancers were diagnosed within the Asia-Pacific region (approximately 404,000 cases at a rate of 30 per 100,000), with the greatest number of those occurring in China (46%), Japan (14%), and Indonesia (12%). Incidence rates varied by around 10-fold across the region, ranging from an estimate of 9 per 100,000 in Mongolia up to 88 per 100,000 in New Caledonia and 92 per 100,000 in French Polynesia (Table 1 and Figure 1). Australia (86 per 100,000) and New Zealand (85 per 100,000) also had much higher incidence rates than any of the other major countries in the region. The highest incidence of breast cancer for Eastern Asia occurred in Japan and South Korea (both 52 per 100,000) and for South-Eastern Asia the highest rate was in Singapore (65 per 100,000).

Figure 1 Breast cancer incidence, mortality and mortality rate: incidence rate ratio (MR:IR) for Asia-Paci fi c countries, 2012. Notes: Rates were age-standardised to the World Standard Population17and expressed per 100,000 females. All categories were based on quintiles. Data source: GLOBOCAN6.

Breast cancer was the most common type of cancer among females in the Asia-Pacific, accounting for 18% of all cancer diagnoses. It also ranked fi rst for females in the majority of countries within the region for which estimates were available (19 out of 26), except for Cambodia and Papua New Guinea where there were more cervical cancers, China and North Korea where there were a higher number of lung cancer cases, South Korea where breast cancer was second behind thyroid cancer, Laos where it ranked second aer liver cancer and Mongolia where breast cancer was the fih most common type of cancer diagnosed for females.

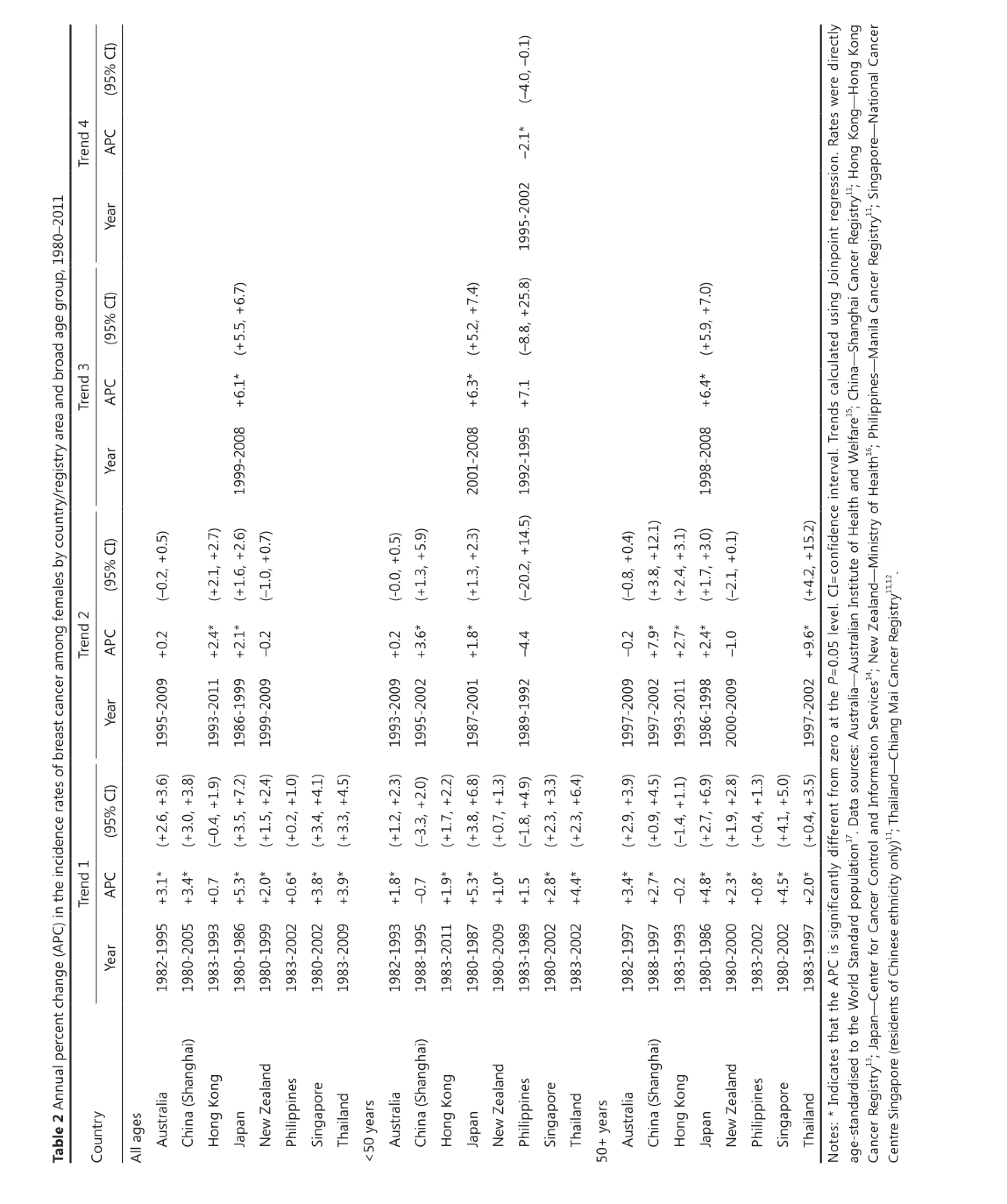

Incidence by age

Globally, one in three women (33%) diagnosed with breast cancer were estimated to be aged under 50 at the time of diagnosis during 2008, compared to 42% throughout the Asia-Pacific region and 47% within the subregion of South-Eastern Asia.e proportion of female breast cancers that were diagnosed among women under 50 years of age ranged from 21% in Australia to 55% in South Korea and Laos and 58% in Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea (data not shown).

A peak in the age-speci fi c incidence rates occurred in Australia for women 50-69 years old (Figure 2), coinciding with the target age range for screening. Incidence rates in the Philippines continued to increase with advancing age. In contrast, age-speci fi c incidence in Hong Kong, Japan andailand either plateaued or began to decrease for women aged 50 years and older.

Incidence by stage

Figure 2 Age-specific incidence rates of breast cancer among selected countries, 2004-2008. Notes: Data was for 2004-2008 except for Philippines (2004-2007) and Thailand (2003-2007). Data for Philippines available to ages 80+. Data sources: Australia—Australian Institute of Health and Welfare15; Hong Kong—Hong Kong Cancer Registry13; Japan—Center for Cancer Control and Information Services14; Philippines (Manila) and Thailand (Chiang Mai)—International Association of Cancer Registries20.

The stage at which breast cancer was diagnosed varied greatlythroughout the Asia-Pacific region. More than half of the breast cancers in New South Wales, Australia (51%)21and South Korea (56%)22were detected at an early (localised) stage. Chiang Mai in Thailand had 21% diagnosed when localised (although a further 52% were diagnosed at ‘locally advanced’—a category not de fi ned by other regions)23. Under the alternate staging system of categories I to IV, Japan had a high proportion of Stage I diagnoses (47% when excluding Stage 0)24, as did the state of Queensland in Australia (48%)25, while Singapore, China (Beijing) and Hong Kong had lower proportions ranging from 27% to 31%26-28. Malaysia had only 14% of breast cancers diagnosed at Stage I, but the unstaged category was very large (36%)29.

Even within countries there were oen substantial disparities in stage at diagnosis between regions and/or ethnic groups. In New Zealand, Pacific Islanders tended to have fewer localised breast cancers diagnosed and a higher proportion of distant cancers, particularly when compared with women who were neither Maori nor Pacific Islanders30. Within China, women living in Beijing had a higher percentage of breast cancers detected at stage I (27%) and fewer stage IV cancers (0.3%) than other regions, particularly Sichuan (stage I: 3%, stage IV: 5%)27.

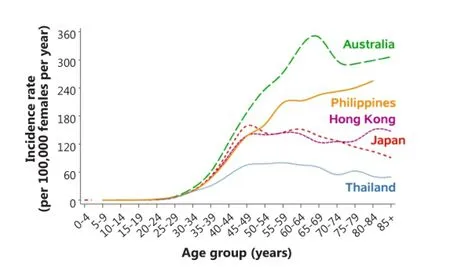

Incidence trends

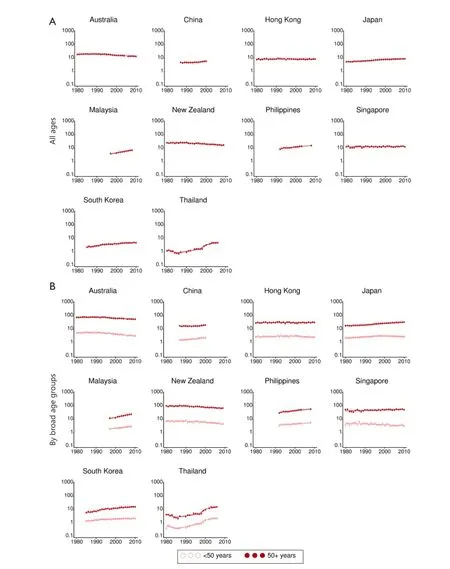

Figure 3 Breast cancer incidence rate trends for selected Asia-Paci fi c countries, 1980—2011. Notes: Y-axis is shown on a log scale. Rates were age-standardised to the World Standard Population17, and expressed per 100,000 female population. Years available differ by country, and sometimes by age groups. Singapore data was only available for residents of Chinese ethnicity. Data sources: Australia—Australian Institute of Health and Welfare15; China—Shanghai Cancer Registry11; Hong Kong—Hong Kong Cancer Registry13; Japan—Center for Cancer Control and Information Services14; New Zealand—Ministry of Health16; Philippines—Manila Cancer Registry11; Singapore—National Cancer Centre Singapore11; Thailand—Chiang Mai Cancer Registry11,12.

Significant increases in breast cancer incidence in recent years were observed in several Asian countries (Table 2 and Figure 3),with incidence rates increasing by 3% to 4% per year in China (Shanghai), Singapore and Thailand. The largest rise was reported in Japan, where signi fi cant increases from 1980 onwards culminated in an average increase of 6% per year between 1999-2008. A different pattern was seen for both Australia and New Zealand, where incidence rates increased until the mid to late 1990s, but have since stabilised.

Similar incidence rate trends were found in both the under 50 and 50 and over age groups for female breast cancer within Australia and Japan. However, rates were increasing more rapidly for older women in China (Shanghai), Hong Kong, Singapore andailand, while in New Zealand the trend was increasing for those aged under 50 compared to some evidence of a possible decrease in incidence over the last decade for women aged 50 years and over.

Mortality rates

About 522,000 females (13 per 100,000 population) were estimated to have died from breast cancer globally during 2012, including almost 116,000 deaths (22%) throughout the Asia-Pacific region at a rate of 8 per 100,000 (Table 1). China accounted for 41% of female breast cancer deaths within the region, followed by Indonesia (17%) and Japan (12%). Mortality rates by subregion varied from 6 per 100,000 in Eastern Asia to 14 per 100,000 in South-Eastern Asia and 16 per 100,000 in Oceania. Fiji was reported as having the highest mortality rate for female breast cancer in the Asia-Pacific (28 per 100,000) followed by the Solomon Islands (24 per 100,000 population) and New Caledonia (23 per 100,000), although the absolute number of deaths due to breast cancer in each of these countries was small (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Breast cancer was estimated to account for 9% of cancerrelated deaths among females in the Asia-Paci fi c region overall, ranking fourth behind lung, liver and stomach cancers. However, it was the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for females in several countries including Fiji, the Solomon Islands (both 27% of all cancer-related deaths), Malaysia (25%), the Philippines (23%), Indonesia (22%), New Caledonia, Vanuatu (both 21%), Singapore (20%) and Samoa (13%) and was the second most frequent in Guam (19%), French Polynesia (18%), Brunei (17%), Australia, New Zealand (both 16%), Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste (both 15%) and North Korea (12%).

Mortality by age

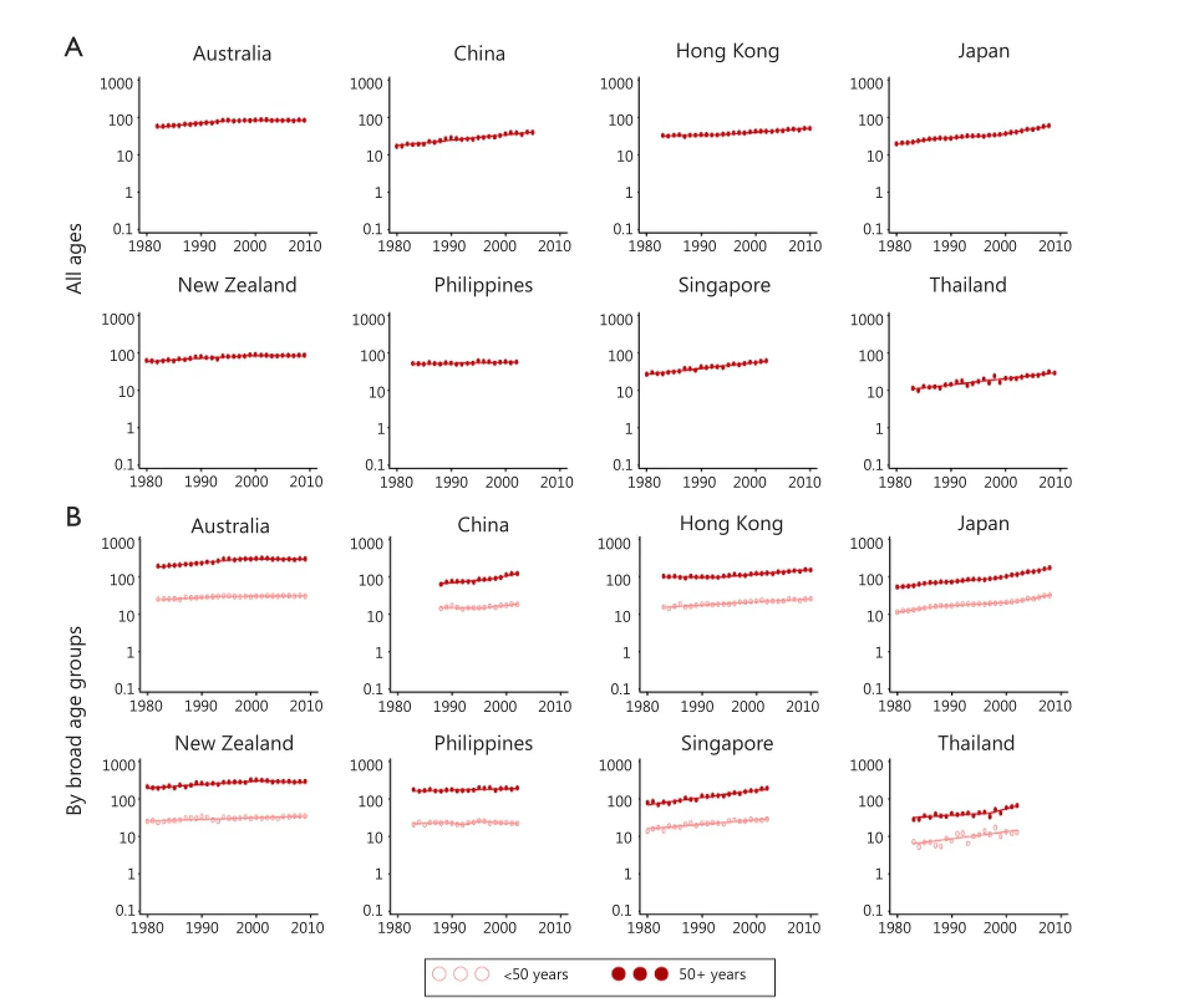

Mortality trends

Breast cancer mortality has been decreasing by an average of about 2% per year for females of all ages in Australia (2000-2011), and New Zealand (1989-2009), while the corresponding trends were stable for Hong Kong and Singapore (Table 3 and Figure 4). In contrast, overall breast cancer mortality rates have increased in several other countries, with the largest rises recorded in Malaysia (6% per year between 1997-2008) and Thailand (7% per year between 2000-2006, with an average annual increase of 9% from 1985 onwards).

Signi fi cant di ff erences were found in breast cancer mortality trends by age group in eight of the ten countries for which trend data were available. The exceptions were China and Thailand, where mortality rates were increasing rapidly irrespective of the age at death. In Australia and New Zealand there was a larger decrease in mortality rates for females under 50 years of age compared to those 50 years or older; in Hong Kong, a signi fi cant decrease was recorded in the under 50 age group while mortality rates were stable for females 50 years of age and over; in Japan and Singapore, breast cancer mortality was decreasing for younger females but increasing in the older age group; and in Malaysia, the Philippines and South Korea, although rates were increasing in both age groups, the rate of increase was lower for females under 50 years of age.

Mortality to incidence rate ratio

The value of MR:IR for breast cancer was slightly lower in the Asia-Pacific region compared to the world average (0.27 and 0.30 respectively, Table 1). Within the region, MR:IR was lowest in Oceania (0.20) and highest in South-Eastern Asia (0.41). Country-speci fi c estimates for MR:IR ranged from 0.12 in South Korea and 0.16 in Australia to 0.51 in Myanmar and the Solomon Islands and 0.53 in Papua New Guinea (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Discussion

Incidence

Figure 4 Breast cancer mortality rate trends for selected Asia-Paci fi c countries, 1980-2011. Notes: Y-axis is shown on a log scale. Rates were age-standardised to the World Standard Population17, and expressed per 100,000 female population. Years available differ by country. Data source: World Health Organization18.

Two main differences are apparent when comparing the descriptive epidemiology of breast cancer in Asia to the West36. Incidence rates tend to be much lower for females in Asia (although the gap is decreasing). The other striking feature is the distribution in age at diagnosis, with the peak being in the 45-50 age range within many Asian countries, while a median of 55-60 years old is typical in most Western countries36-38. Even so, the age-speci fi c incidence rates of breast cancer are still considerably higher in Australia and New Zealand compared to Asian countries among women younger than 50. It is generally accepted that the risk factors for breast cancer are similar throughout the world, even though most of the aetiological research has been conducted on Western populations2. However, the di ff erences highlighted above suggest that the prevalence and composition of risk factors varies between the countries.

It is possible that the higher median age at diagnosis among women in Western countries could be partly explained by the population-based mammography breast screening that is widely available in these countries, which typically targets women aged 50 years and over5. One criticism of these programs is that asymptomatic breast tumours that would not progress further are over-diagnosed5, which has the potential to arti fi cially in fl ate the incidence rate among women over 50 years old, and hence increase the observed median age at diagnosis.

However, it seems likely that most of the age di ff erence is real. At least some of the tendency towards a younger age of onset for female breast cancer in Asia compared to Western countries such as Australia and New Zealand can be attributed to differences in life expectancy, with a greater proportion of the population in the younger age groups for females in developing countries7. Researchers have also identi fi ed a strong birth cohort e ff ect39,40that is reducing over time due to cultural changes. A large portion of the increase in breast cancer incidence being observed in many Asia-Paci fi c countries is likely due to the adoption of a more “Westernised” lifestyle, including adverse changes to diet, physical activity and fertility31,41-44.is e ff ect has been greatest among younger women living in urban areas of lower and middle income countries9.

Reproductive issues that impact on lifetime exposure to estrogen have a particularly crucial role in the potential for development of female breast cancer45,46. Numerous case-control studies have established that the main risk factors for breast cancer in Asian women include early menarche, late menopause, older age at first delivery, and a lower number of full term pregnancies47-51.e prevalence of these reproductive risk factors is on the rise in Asia44. For example, family planning initiatives have brought about sustained declines in fertility rates across the region over recent decades52,53.

Genetic interactions may also alter the importance of some causal factors between ethnic groups2,54. Signi fi cant di ff erences in age-speci fi c incidence rates between Malay, Chinese and Indian women living in Singapore have been aributed to variations in the association between childbirth and pre-menopausal breast cancer by ethnicity55,56.

Other issues that may in fl uence reported di ff erences in breast cancer incidence between countries include socio-economic status, utilisation of mammography and the scope and accuracy of cancer registry data57. Higher rates of breast cancer are generally associated greater personal wealth, ease of access to breast cancer screening and areas where there are mechanisms in place for full population-based collection of all cases of cancer.

One of the consequences of the disparity in the average age at diagnosis between more developed and less developed countries is a marked difference in the distribution of tumour types; a greater proportion of cases in Asia are currently estrogen or progesterone receptor negative (ER–/PR–)9,36. However, the distribution appears to be changing in some countries. A study in Malaysia58showed that between 1994 and 2008, the proportion of ER+ breast cancers increased by 2% for every 5 years cohort. This may be due to an increase in the incidence of ER+ cases while the incidence of ER– cases remained fairly stable, giving rise to a higher proportion of ER+ cancers over time.

It is therefore expected that the incidence rate, median age and biological profile of breast cancers throughout the Asia-Pacific will eventually come to more closely resemble that of Australia and New Zealand as changes to lifestyle and screening practices become more widespread, combined with a shift towards an older population structure31,36-38,58.

Mortality

Mortality trends varied across the region, with large increases inseveral Asian countries contrasting with decreases in both Australia and New Zealand. A 3-fold increase in the breast cancer mortality rate has been predicted in South Korea between 1983 and 2020 if current paerns continue59. Trends can also vary within a country. Guo et al.60reported a 20% increase in breast cancer mortality rates in rural parts of China compared to a decrease of 7% in urban areas between 1997-2001 and 2007-2009, although mortality rates still remained higher in urban areas.

Interesting results emerged for mortality trends by age. We found that in most countries, mortality from female breast cancer was either decreasing more quickly, or alternatively, increasing at a slower pace, for females under 50 years of age compared to those who were over 50.is was most noticeable in Japan and Singapore where there was a signi fi cant decrease in mortality for younger females compared to a signi fi cant increase in the breast cancer death rate among those who were older.

Survival from breast cancer depends mainly on early detection and access to optimal treatment. There are several cultural and economic obstacles involved in managing breast cancer in parts of the Asia-Pacific region, including misunderstanding about the disease (such as the incorrect idea that surgery will cause cancer cells to spread more quickly), geographical isolation, lack of education and awareness, inadequate diagnostic equipment and treatment facilities, competing health care needs and a reliance on traditional remedies1,9,37.ese factors may in fl uence treatment decisions and adherence2. Social implications, such as the possibility of abandonment following a mastectomy or the perception that a breast cancer patient may become a burden to her family37,61, can also cause fear, denial and reluctance to visit a doctor.

Delayed presentation is a major problem that stems from these barriers, with a high proportion of women with breast cancer in less developed Asian countries being diagnosed with advanced disease1,2,37. Tumours tend to be large with poorer histological grade, and many have lymph node involvement or distant metastases1,62,63.

Access to mammography is limited in many developing countries9. Hence, the majority of female breast cancer cases in most parts of the Asia-Pacific region are only detected after symptoms appear1. It is uncertain whether mammography screening would be as effective for women in Asia as it is for Caucasians, due to the tendency for Asians to have smaller volume breasts with denser tissue, even among post-menopausal women2,64. Studies have, however, shown that screening by mammography is superior to clinical examination for detecting breast cancer early among Japanese women64, and research in Singapore found that the spectrum of mammographic abnormalities observed was similar to what would be expected in a Caucasian population65. Apart from the physiological differences, there are also other issues to consider in regard to the use of mammography. Asian women have been reported to under-utilise breast cancer screening due to a variety of reasons such as a lack of knowledge, concerns about modesty, and the need for more encouragement from family and physicians64,66,67. Given the limited resources in many less developed areas, it has been suggested that, as a first step, available money would be better spent on improving breast cancer awareness through community-based education programs, teaching self-examination and encouraging women to obtain medical assistance for diagnosis and treatment68,69.

Ideal management of breast cancer requires a multidisciplinary team, comprising the breast surgeon, radiologist, pathologist, radiation and medical oncologists, plastic surgeon, and a breast care nurse specialist. It also depends on a robust and equitable health care system, with adequate staffing and resources to provide optimal treatment. Low and middle income countries form the majority of the Asia-Paci fi c region, where the proportion of government spending on health care is inadequate. Total expenditure on health as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product is 5% or lower in many parts of the Asia-Pacific region compared to 9% in Australia and Japan and 10% in New Zealand70.e lower priority given to health expenditure in some countries, particularly for a female-specific disease such as breast cancer, means that even women who seek early medical intervention oen do not receive appropriate advice or treatment1.

Tumour biology and ethnicity play a smaller role in breast cancer survival.ere are racial di ff erences in histological types of breast cancer as well as the molecular pro fi le of breast cancer71. Triple negative breast cancer, where the tumour has an absence of oestrogen and progesterone receptors and no overexpression of human epidermal growth factor, has a poorer prognosis compared to other molecular subtypes72. Reports indicate that this type of breast cancer is relatively more common in the Asia-Pacific region compared to North America or Europe9. Researchers in Sarawak, Malaysia, showed that the triple negative subtype accounted for a higher proportion of breast cancer cases in Sarawak natives (37%) and Malay women (33%) compared to those of Chinese ethnicity (23%)73. Another study from Malaysia and Singapore found an independent effect of ethnicity on survival following female breast cancer, with poorer survival for Malay women compared to their Chinese and Indian counterparts74. In particular, Malay ethnicity was associated with more aggressive tumour biology as evidenced by a higher risk of axillary lymph node metastasis for tumours of a similar size.

Other reasons for survival disparities by ethnicity are yet to be fully determined, but may consist of a combination ofsocio-economic status, cultural factors, response to treatment and differences in lifestyle74. For example, treatments such as hormonal therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy that work well for Caucasian women may not be as effective in Asia due to di ff erences in tumour biology and metabolism of drugs2,38.

A lot of work has been done over the last decade to establish appropriate strategies for dealing with female breast cancer in developing countries with the aim of improving outcomes.e Breast Health Global Initiative was set up in 2003 by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Centre in Seattle to develop economically feasible and culturally sensitive guidelines for breast cancer care in low and middle income countries75,76.ese guidelines cover the whole spectrum of breast cancer control (prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment). Given the differentials in available funding, it would not be practical for low income countries to provide breast cancer care at the same level as high income countries. Therefore, the guidelines are stratified into basic, limited, enhanced and maximal depending on the resources that are available37,77. The aim of this stratification model is to ensure that even in low resource settings, women with breast cancer are managed appropriately.

Encouraging signs are starting to appear. Recent improvements in the survival rate of breast cancer patients have been reported in South Korea33and Malaysia78. The mortality trends that we have reported here for women under 50 years of age would also seem to indicate that the message regarding the importance of early detection may be gaining traction among younger females throughout parts of the Asia-Pacific region. However, the full impact of programs such as the Breast Health Global Initiative will remain difficult to measure due to the lack of national or regional cancer data collections in many less developed countries79.

Limitations

Our reporting of trends was limited in that data over time were only available from a relatively small number of countries/ registries. Consequently, gaps remain in the description of how the incidence and mortality of female breast cancer is changing throughout the entire Asia-Paci fi c region.

We also did not report survival data mainly due to a lack of recent, reliable and comparable information from less developed countries, but have instead provided data on MR:IR as a proxy measure. Some of the higher values for MR:IR may be biased upwards as they could possibly represent better recording of mortality data compared to breast cancer incidence in those countries.

Conclusion

Although breast cancer incidence rates currently remain lower in developing countries of the Asia-Pacific compared to Australia or New Zealand, the rapid increases that are being experienced in places with large populations such as China and Japan will continue to shithe worldwide burden of this disease towards Asia80. Female breast cancer must therefore be a ff orded a higher priority for health spending in the region. While opportunities exist for worldwide collaborations to improve outcomes for women with breast cancer, at the same time it is clear that the approach to breast cancer control needs to be evaluated and tailored to the different situations in each country68,77,81. More emphasis also needs to be placed on cancer prevention strategies and the development of population-based registration systems for the effective planning and monitoring of cancer control programs82,83.e ultimate goal is to ensure that the declines in breast cancer mortality rates seen in Australia and New Zealand are replicated in other countries throughout the Asia-Pacific region in the near future.

Acknowledgements

Peter Baade was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship (Grant No.1005334).

Con fl ict of interest statement

No potential con fl icts of interest are disclosed.

1. Agarwal G, Pradeep PV, Aggarwal V, Yip CH, Cheung PS. Spectrum of breast cancer in Asian women. World J Surg 2007;31:1031-1040.

2. Bhoo-Pathy N, Yip CH, Hartman M, Uiterwaal CS, Devi BC, Peeters PH, et al. Breast cancer research in Asia: adopt or adapt Western knowledge? Eur J Cancer 2013;49:703-709.

4. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69-90.

5. Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NA, Muller JM, Pyke CM, Baade PD.e descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: an international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol 2012;36:237-248.

6. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C,et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013.

7. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social A ff airs, Population Division. World Population Prospects:e 2010 Revision, CD-ROM Edition; 2011.

8. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108.

9. Green M, Raina V. Epidemiology, screening and diagnosis of breast cancer in the Asia–Paci fi c region: Current perspectives and important considerations. Asia-Paci fi c Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008;4:S5-S13.

10. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

11. Ferlay J, Parkin D, Curado M, Bray F, Edwards B, Shin H, et al. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Volumes I to IX: IARC CancerBase No. 9 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available online: hp://ci5.iarc.fr/ CI5plus/ci5plus.htm; accessed 12 Nov 2013.

12. Chiang Mai Cancer Registry. Chiang Mai Cancer Registry Annual Reports, 2000-2009 Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University; 2010. Available online: hp://www.med.cmu.ac.th/hospital/tumor/ report.html; accessed 12 Nov 2013.

13. Hospital Authority. Cancer Statistics Query System (CanSQS). Available online: hp://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/statistics. html. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Cancer Registry; 2013. Available online: hp://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/statistics.html; accessed 12 Nov 2013.

14. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services. Cancer statistics in Japan, Incidence 1975-2008. National Cancer Center, Japan; 2013. Available online: hp://ganjoho.jp/pro/statistics/ en/table_download.html

15. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality Workbooks. Canberra: AIHW; 2012. Available online: hp://www.aihw.gov.au/acim-books/; accessed 11 Nov 2013.

16. Ministry of Health. Breast cancer in New Zealand custom tabulation, 1948-2009. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2013.

17. Segi M. Cancer mortality for selected sites in 24 countries (1950-1957). Sendai, Japan: Department of Public Health, Tohoku University of Medicine; 1960.

18. World Health Organization. WHO Mortality Database (released 1 May 2013). Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available online: hp://www. who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality_rawdata/en/index.html; accessed 12 Nov 2013.

19. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335-351.

20. Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, Gombe Mbalawa C, Kohler B, Pi?eros M, et al. editors. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. X (electronic version). Lyon: IARC; 2013.

21. New South Wales Central Cancer Registry. Top 20 cancer sites by stage, 2004-2008. Sydney: Cancer Institute NSW & NSW Government Health; 2010. Available online: hp://www.statistics. cancerinstitute.org.au/prodout/top20_extent/top20_extent_ lhnres_incid_2004-2008_NSW_2.htm; accessed 11 Dec 2013.

22. Korea Central Cancer Registry. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2010. Seoul: Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center and Ministry of Health & Welfare; 2012.

23. Chiang Mai Cancer Registry. Chiang Mai Cancer Registry Annual Report, 2009 Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University; 2010. Available online: hp://www.med.cmu.ac.th/hospital/tumor/report.html; accessed 12 Nov 2013.

24. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center. Cancer Statistics in Japan 2012. Tokyo: Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research; 2012.

25. Baade PD, Turrell G, Aitken JF. Geographic remoteness, arealevel socio-economic disadvantage and advanced breast cancer: a cross-sectional, multilevel study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:1037-1043.

26. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Hong Kong Cancer Statistics 2007. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority; 2009.

27. Wang Q, Li J, Zheng S, Li JY, Pang Y, Huang R, et al. Breast cancer stage at diagnosis and area-based socioeconomic status: a multicenter 10-year retrospective clinical epidemiological study in China. BMC Cancer 2012;12:122.

28. National Registry of Diseases O ffi ce. Health Factsheet: Trends of female breast cancer in SIngapore, 2006-2010. Singapore: NRDO; 2012.

29. Zainal Ari ffi n O, Nor Saleha IT. National Cancer Registry Report 2007. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2011.

30. McKenzie F, Je ff reys M, ‘t Mannetje A, Pearce N. Prognostic factors in women with breast cancer: inequalities by ethnicity and socioeconomic position in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:403-411.

31. Shin HR, Joubert C, Boniol M, Hery C, Ahn SH, Won YJ, et al. Recent trends and paerns in breast cancer incidence among Eastern and Southeastern Asian women. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1777-1785.

32. Wang N, Zhu WX, Xing XM, Yang L, Li PP, You WC. Time trends of cancer incidence in urban beijing, 1998-2007. Chin J Cancer Res 2011;23:15-20.

33. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in2010. Cancer Res Treat 2013;45:1-14.

34. Katanoda K, Matsuda T, Matsuda A, Shibata A, Nishino Y, Fujita M, et al. An updated report of the trends in cancer incidence and mortality in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013;43:492-507.

35. Troisi R, Altantsetseg D, Davaasambuu G, Rich-Edwards J, Davaalkham D, Tretli S, et al. Breast cancer incidence in Mongolia. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:1047-1053.

36. Leong SP, Shen ZZ, Liu TJ, Agarwal G, Tajima T, Paik NS, et al. Is breast cancer the same disease in Asian and Western countries? World J Surg 2010;34:2308-2324.

37. Yip CH. Breast Cancer in Asia. In: Verma M. eds. Methods in Molecular Biology, Cancer Epidemiology, Vol 471. Totowa, NJ: Springer Science; 2009:51-64.

38. Toi M, Ohashi Y, Seow A, Moriya T, Tse G, Sasano H, et al.e Breast Cancer Working Group presentation was divided into three sections: the epidemiology, pathology and treatment of breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40 Suppl 1:i13-18.

39. Seow A, Du ff y SW, McGee MA, Lee J, Lee HP. Breast cancer in Singapore: trends in incidence 1968-1992. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:40-45.

40. Mousavi-Jarrahi SH, Kasaeian A, Mansori K, Ranjbaran M, Khodadost M, Mosavi-Jarrahi A. Addressing the younger age at onset in breast cancer patients in Asia: an age-period-cohort analysis of fiy years of quality data from the international agency for research on cancer. ISRN Oncol 2013;2013:429862.

41. Park S, Bae J, Nam BH, Yoo KY. Aetiology of cancer in Asia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008;9:371-380.

42. Porter P. “Westernizing” women’s risks? Breast cancer in lowerincome countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:213-216.

43. Afolabi IR. Towards prevention of breast cancer in the Paci fi c: in fl uence of diet and lifestyle. Pac Health Dialog 2007;14:67-70.

44. Lertkhachonsuk AA, Yip CH, Khuhaprema T, Chen DS, Plummer M, Jee SH, et al. Cancer prevention in Asia: resource-strati fi ed guidelines from the Asian Oncology Summit 2013. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e497-507.

45. Key TJ, Verkasalo PK, Banks E. Epidemiology of breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:133-140.

46. Parsa P, Parsa B. E ff ects of reproductive factors on risk of breast cancer: a literature review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009;10:545-550.

47. Nagata C, Hu YH, Shimizu H. E ff ects of menstrual and reproductive factors on the risk of breast cancer: meta-analysis of the case-control studies in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res 1995;86:910-915.

48. Suh JS, Yoo KY, Kwon OJ, Yun IJ, Han SH, Noh DY, et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors related to the risk of breast cancer in Korea. Ovarian hormone e ff ect on breast cancer. J Korean Med Sci 1996;11:501-508.

49. Gao YT, Shu XO, Dai Q, Poer JD, Brinton LA, Wen W, et al. Association of menstrual and reproductive factors with breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Int J Cancer 2000;87:295-300.

50. Liu YT, Gao CM, Ding JH, Li SP, Cao HX, Wu JZ, et al. Physiological, reproductive factors and breast cancer risk in Jiangsu province of China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:787-790.

51. Yanhua C, Geater A, You J, Li L, Shaoqiang Z, Chongsuvivatwong V, et al. Reproductive variables and risk of breast malignant and benign tumours in Yunnan province, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:2179-2184.

52. Bongaarts J, Sinding S. Population policy in transition in the developing world. Science 2011;333:574-576.

53. Fan L, Zheng Y, Yu KD, Liu GY, Wu J, Lu JS, et al. Breast cancer in a transitional society over 18 years: trends and present status in Shanghai, China. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;117:409-416.

54. Park SK, Kim Y, Kang D, Jung EJ, Yoo KY. Risk factors and control strategies for the rapidly rising rate of breast cancer in Korea. J Breast Cancer 2011;14:79-87.

56. Verkooijen HM, Yap KP, Bhalla V, Chow KY, Chia KS. Multiparity and the risk of premenopausal breast cancer: di ff erent e ff ects across ethnic groups in Singapore. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:553-558.

57. Hortobagyi GN, de la Garza Salazar J, Pritchard K, Amadori D, Haidinger R, Hudis CA, et al.e global breast cancer burden: variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin Breast Cancer 2005;6:391-401.

58. Yip CH, Pathy NB, Uiterwaal CS, Taib NA, Tan GH, Mun KS, et al. Factors a ff ecting estrogen receptor status in a multiracial Asian country: an analysis of 3557 cases. Breast 2011;20 Suppl 2:S60-64. 59. Choi Y, Kim YJ, Shin HR, Noh DY, Yoo KY. Long-term prediction of female breast cancer mortality in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2005;6:16-21.

60. Guo P, Huang ZL, Yu P, Li K. Trends in cancer mortality in China: an update. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2755-2762.

61. Moore MA, Manan AA, Chow KY, Cornain SF, Devi CR, Triningsih FX, et al. Cancer epidemiology and control in peninsular and island South-East Asia - past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2010;11 Suppl 2:81-98.

62. Yip CH, Taib NA, Mohamed I. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006;7:369-374.

63. Aryandono T, Harijadi, Soeripto. Survival from operable breast cancer: prognostic factors in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006;7:455-459.

64. Tan SM, Evans AJ, Lam TP, Cheung KL. How relevant is breast cancer screening in the Asia/Paci fi c region? Breast 2007;16:113-119.

65. Sng KW, Ng EH, Ng FC, Tan PH, Low SC, Chiang G, et al.Spectrum of abnormal mammographic fi ndings and their predictive value for malignancy in Singaporean women from a population screening trial. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2000;29:457-462.

66. Parsa P, Kandiah M, Abdul Rahman H, Zulke fl i NM. Barriers for breast cancer screening among Asian women: a mini literature review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006;7:509-514.

67. Sim HL, Seah M, Tan SM. Breast cancer knowledge and screening practices: a survey of 1,000 Asian women. Singapore Med J 2009;50:132-138.

68. Harford JB. Breast-cancer early detection in low-income and middle-income countries: do what you can versus one size fi ts all. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:306-312.

69. Yip CH, Taib NA. Challenges in the management of breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Future Oncol 2012;8:1575-1583.

71. Bhikoo R, Srinivasa S, Yu TC, Moss D, Hill AG. Systematic review of breast cancer biology in developing countries (part 2): asian subcontinent and South East Asia. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:2382-2401.

72. Boyle P. Triple-negative breast cancer: epidemiological considerations and recommendations. Ann Oncol 2012;23 Suppl 6:vi7-12.

73. Devi CR, Tang TS, Corbex M. Incidence and risk factors for breast cancer subtypes in three distinct South-East Asian ethnic groups: Chinese, Malay and natives of Sarawak, Malaysia. Int J Cancer 2012;131:2869-2877.

74. Bhoo-Pathy N, Hartman M, Yip CH, Saxena N, Taib NA, Lim SE, et al. Ethnic di ff erences in survival aer breast cancer in South East Asia. PLoS One 2012;7:e30995.

75. Anderson BO, Braun S, Carlson RW, Gralow JR, Lagios MD, Lehman C, et al. Overview of breast health care guidelines for countries with limited resources. Breast J 2003;9 Suppl 2:S42-50.

76. Anderson BO, Shyyan R, Eniu A, Smith, Yip CH, Bese NS, et al. Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: an overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative 2005 guidelines. Breast J 2006;12 Suppl 1:S3-15.

77. Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, Shyyan R, Sener SF, Eniu A, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries: overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative Global Summit 2007. Cancer 2008;113:2221-2243.

78. Taib NA, Akmal M, Mohamed I, Yip CH. Improvement in survival of breast cancer patients - trends over two time periods in a single institution in an Asia Paci fi c country, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:345-349.

79. Anderson BO, Cazap E, El Saghir NS, Yip CH, Khaled HM, Otero IV, et al. Optimisation of breast cancer management in lowresource and middle-resource countries: executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:387-398.

80. Linos E, Spanos D, Rosner BA, Linos K, Hesketh T, Qu JD, et al. E ff ects of reproductive and demographic changes on breast cancer incidence in China: a modeling analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1352-1360.

81. Love RR. De fi ning a global research agenda for breast cancer. Cancer 2008;113:2366-2371.

82. Shin HR, Carlos MC, Varghese C. Cancer control in the Asia Paci fi c region: current status and concerns. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012;42:867-881.

83. Curado MP, Voti L, Sortino-Rachou AM. Cancer registration data and quality indicators in low and middle income countries: their interpretation and potential use for the improvement of cancer care. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:751-756.

Cite this article as:Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Yip CH, Baade PD. Incidence and mortality of female breast cancer in the Asia-Paci fi c region. Cancer Biol Med 2014;11:101-115. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.02.005

Danny R. Youlden

E-mail: dannyyoulden@cancerqld.org.au

Received January 20, 2014; accepted February 11, 2014. Available at www.cancerbiomed.org

Copyright ? 2014 by Cancer Biology & Medicine

Methods:Statistical information about breast cancer was obtained from publicly available cancer registry and mortality databases (such as GLOBOCAN), and supplemented with data requested from individual cancer registries. Rates were directly age-standardised to the Segi World Standard population and trends were analysed using joinpoint models.

Results:Breast cancer was the most common type of cancer among females in the region, accounting for 18% of all cases in 2012, and was the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths (9%). Although incidence rates remain much higher in New Zealand and Australia, rapid rises in recent years were observed in several Asian countries. Large increases in breast cancer mortality rates also occurred in many areas, particularly Malaysia andailand, in contrast to stabilising trends in Hong Kong and Singapore, while decreases have been recorded in Australia and New Zealand. Mortality trends tended to be more favourable for women aged under 50 compared to those who were 50 years or older.

Conclusion:It is anticipated that incidence rates of breast cancer in developing countries throughout the Asia-Pacific region will continue to increase. Early detection and access to optimal treatment are the keys to reducing breast cancerrelated mortality, but cultural and economic obstacles persist. Consequently, the challenge is to customise breast cancer control initiatives to the particular needs of each country to ensure the best possible outcomes.

Cancer Biology & Medicine2014年2期

Cancer Biology & Medicine2014年2期

- Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- Polymeric nanocomposites loaded with fluoridated hydroxyapatite Ln3+ (Ln = Eu or Tb)/iron oxide for magnetic targeted cellular imaging

- An unusual case of aggressive systemic mastocytosis mimicking hepatic cirrhosis

- Spindle cell carcinoma of the breast as complex cystic lesion: a case report

- Effects of postmastectomy radiotherapy on prognosis in different tumor stages of breast cancer patients with positive axillary lymph nodes

- Clinico-pathological signi fi cance of extra-nodal spread in special types of breast cancer

- Research progress on the anticarcinogenic actions and mechanisms of ellagic acid