Complementiser and Complement Clause Preference for Verb-Heads in the Written English of Nigerian Undergraduates

Juliet Udoudom & Ogbonna Anyanwu

University of Uyo, Nigeria

1. Introduction

Linguistic behaviour, whether in native or non-native linguistic environments, is determined by the ability of the language-user to make appropriate linguistic choices from a plethora of alternatives available in the relevant language system. Such choices may be made from the sound system, the vocabulary, the syntactic or the semantic system of the language in use, with the result that appropriate pronunciation is chosen for intelligible speech production to be achieved. Also, suitable lexical items and appropriate collocational patterns are selected for the construction of phrases, clauses, and sentences;and lexical items are utilized for the expression of intended meaning. The linguistic choices made by language users are expectedly informed by the existing linguistic principles governing usages in particular language systems (Lyons, 1981, 2008; Chomsky,1966, 1972; Radford, 1988), even though innovations and creativity are established as inherent properties of natural languages (Banjo, 1995; Yule, 2000; Chomsky, ibid.). For instance, Chomsky (1972) observes in relation to language users’ sentence construction practices:

The normal use of language is innovative in the sense that much of what we say in the course of normal language use is entirely new, not a repetition of anything that we have heard before,and not even similar in pattern…to sentences or discourse that we have heard in the past.(Chomsky, 1972, p. 12)

However, linguistic innovations and creativity are expected to be practised in conformity with the norms of the language in use, given that adherence to such norms make for uniformity in usage and cohesiveness within a particular speech community. Some syntactic studies have shown, however, that linguistic principles are not always adhered to; hence, appropriate linguistic choices are not always made. In English non-native linguistic contexts such as in Nigeria, the grammatical constructions of speakers of English as a second language have been observed to be fraught with deviant usages,resulting from inappropriate linguistic choices (Banjo, 1969, 1979; Adesanoye, 1973;Eka, 1979; Jibril, 1979; Jowit, 1991; Alo & Mesthrie, 2008, etc.).

The present paper investigates an aspect of the syntactic construction of Nigerian users of English as a second language. It specifically examines the preference of complementiser and complement clause type for certain verb-heads by some Nigerian undergraduate users of English. The investigation seeks to determine and highlight the complementiser and complement clause types that are most preferred by the respondents:this is with a view to evaluate the appropriateness of such choices especially when viewed in line with subcategorization features of the verb-heads which select the complementiser and the complement clauses.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: in section 2, we provide an overview of clauses in English, while in sections 3 and 4, we present the methodology and data/discussion of the data respectively. Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Clauses in English

A clause is generally considered to be a group of words with its own verb (finite or non-finite) and its own subject, and is capable of functioning as a single unit within the sentence context in which it occurs. Consider the sentences in (1):

(1) (a) He claimed [that he was hungry]

(b) The items [which were listed to be bought] have been given to him.

(c) The men rented the place [when they arrived for the event].

In (1a-c), the bracketed constituents are clauses functioning as noun object (1a),adjective, describing the noun ‘items’ (1b), and adverbial clause of time (1c). In the same way that clauses can perform object, adjectival or adjunct functions in their containing structures they can also realize complement functions in relevant/appropriate syntactic contexts, since the term ‘complement’ is not a categorial term, but a functional term just as subject and object (cf. Aarts, 2001; Adger, 2003). Traditionally, clauses in English may be distinguished into two types: those which are capable of independent existence and those which are not. The first type of clause is often described variously as a root, independent, super-ordinate, main, matrix or principal clause (Quirk &Greenbaum, 1974). The second type is referred to as a dependent, subordinate or minor clause. This type is so described because it is generally incapable of occurring on its own, instead, it is licensed by some other constituent within the structure in which it occurs for its meaning (ibid., p. 54). It is in this sense that subordinate (minor) clauses are also known as embedded clauses. In (1a-c) above, the bracketed constituents (even though each contains identifiable subjects and verbs) are not independent as shown in(2).

(2) (a) …that he was hungry

(b) …which was listed to be bought

(c) …where the event occurred.

Each of these needs a syntactic host to function as subject, object or complement (cf.Quirk & Greenbaum, 1974; Quirk et al., 1985; Borsely, 1991; Aarts, 2001; Adger, 2003,etc.). The focus of the present paper, however, is on clauses which function to serve as complements to V-heads in English and the kinds of complementisers which introduce them. We will therefore provide an overview on the nature and structure of the types of subordinate clause which regularly serve as complements of verbs in English.

2.1 Overview of complement clauses in English

As stated in the preceding sub-section, clauses which function as complements are typically subordinate clauses, hence they are referred to as complement clauses (Radford,1988, 1997; Borsely, 1991; Aarts, 2001; Adger, 2003; Moravcsik, 2006). Complement clauses are typically introduced by clause-introducers referred to as complementisers.In English,that,whether,forandifare examples of forms that can function as complementisers. The sentences in (3) exemplify complement clauses in English.

(3) (a) We know for certain [thatthe government will approve the project]

(b) The forecast could not really say [whetherit would rain tomorrow]

(c) Both parties would obviously prefer [forthe matter to be resolved amicably]

(d) They wanted to know [ifthey should come]

In each of (3a-d), the bracketed constituent is the complement clause. As can be observed,each group of bracketed constituents has a word at the beginning of the group:thatin (a),whetherin (b),forin (c) andifin (d).

Clauses which function as complements may be classified syntactically into three major sub-types, namely ordinary clauses (OCs), exceptional clauses (ECs), and small clauses (SCs) (Radford, 1988, p. 353). Ordinary clauses like those bracketed in (3) form an S-bar constituent with their immediate constituents: complementiser and sentence (ibid.,p. 294). Complement clauses described as exceptional clauses are typically of the form [NP to VP] as those bracketed in (4) below:

(4) (a) I know [the Chairman to be honest]

(b) Some believe [the verdict to be fair]

(c) I consider [the flight to have arrived early]

(d) They reported [the matter to be before a judge]

As can be observed in (4), exceptional clauses cannot be introduced by an overt complementiser such asfor,if,whether, andthat, and this accounts for the ungrammaticality in (5).

(5) (a) *I know [for the chairman to be honest]

(b) *Some believe [if the verdict to be fair]

(c) *I consider [whether the flight to have arrived early]

(d) *They reported [that the matter to be before a judge]

Thus, based on this property of exceptional clauses, they have the status of S and not S-bar since they lack the complementisers which are constituents of S-bar (ibid., p. 317). Small clauses on the other hand are those bracketed in (6).

(6) (a) They want [Mr. Okpon out of the race]

(b) Some house members believe [the Minister incapable of fraud]

(c) Most people find [education quite exciting]

(d) Why not let [everyone into one hall]

As can be seen, the structure of the bracketed constituents in (6a-d) show that small clauses have the canonical [NP XP] structure, where XP may be instantiated by an adjective phrase, a noun phrase or a prepositional phrase. Also apparent from the structure of small clauses in (6) is that they have neither the C nor the inflection (I)constituents.

The internal structure of each of the clause types shows that the ordinary clause (S-bar)contains both a C and an I constituent; the exceptional clause contains an I constituent but no C and the small clause lacks both the C and I constituents (ibid, p. 356). The small clause has also been referred to as a “verbless clause” (Radford, ibid.; Eka, 1994). Our focus in the present study is on the ordinary clause. Two reasons inform our focus on this syntactically determined clause-type. A cursory look at their constituent parts shows that an ordinary clause contains a complementiser, which, as will be clear later, determines a head’s selection of an appropriate complement clause. Also, verb-heads in English generally select complement clauses with the [C-S] structure. Thus, a complement clause usually contains a complementiser as an obligatory constituent and such a complementiser heads the ordinary clause (Radford, 1988, p. 295; Adger, 2003, p. 290). We shall briefly examine the structure of ordinary clauses in English.

2.2 Internal structure of ordinary clauses

Following the explanation of a clause offered in (2.1) as a group of words with its own subject and verb, the traditional phrase structure (PS) rule expanding clauses is (7), where NP is the maximal phrasal expansion of N, and VP is similarly the maximal phrasal expansion of V.

(7) S→NP modal (M) VP

However, as would be observed from the rule in (7), it does not seem to capture the constituent structure in which the subject NP is preceded by a C such asthat,for,whetherorif. Two possibilities regarding the constituent structure of clauses which contain C constituents have been put forward: first by Emonds (1976, p. 142) and Soames and Perlmutter (1976, p. 63) who note that C is generated within S as a sister to the Subject NP of the relevant clause by a rule such as (8), and second, by Bresnan (1970) who argues that a C and S merge to form a larger clausal unit referred to as S-bar (S’). Bresnan’s (1970)analysis incorporates two PS rules as in (9a) and (9b).

(8) S→C NP M VP

(9) (a) S’→C S

(b) S→NP M VP

The rules in (9) can be represented on a tree schema as in figure 1:

Figure 1. Tree structure representation of an English S-bar constituent

However, as Radford (1981) proposes, to accommodate both the finite indicative clauses as well as infinitival complement clauses within a phrase structure rule schema,and also capture the obvious structural parallelism between the N element in indicative clauses and the infinitival particle ‘to’, it is assumed that M and ‘to’ elements are members of the category inflection (I) (following Chomsky, 1981, p. 18). On this proposal therefore the basic internal structure of ordinary clauses is as specified in the two rules in (10):

(10) (a) S’→C S

(b) S→NP I VP

I indicates whether the relevant complement clause is finite or non-finite. Ordinary clauses are therefore of the schematic form in figure 2.

Figure 2. Tree structure representation of an English ordinary clause

The present study partly follows both Bresnan’s (1970) and Chomsky’s (1981) analyses of the constituent structure of complement clauses in English. It further assumes that a subordinate clause which functions as a complement role must have a complementiser as one of its immediate and obligatory constituents (Radford, 1988, p. 295; Adger,2003). Due to the centrality of the C constituent in clause complementation, we shall provide an overview on the complementiser highlighting its status as a distinct linguistic category.

2.3 Complementisers in English: An overview

Complementisers denote a specific category of words and evidence for the classification of words likethat,whether,forandifas complementisers has been offered in Adger (2003,pp. 290-291) as follows:

(11) (a) they occur at the start of (hence introduce) embedded clauses;

(b) they form constituents with the clauses which follow them and not with the embedding verb of the main clause; and

(c) they would move with their following clauses and not be stranded in the event of pseudo-clefting.

Following Radford (1988, p. 302), it is assumed here that the C can be expanded into a bundlle of features such as (12).

(12) C = [±WH, ±FINITE]

The feature rule of the C constituent in (12) will generate the feature complexes in (13a-d):

(13) (a) [+WH, +FINITE] can be filled by ‘whether/if’

(b) [+WH, -FINITE] can be filled by ‘whether’

(c) [-WH, +FINITE] can be filled by ‘that’

(d) [-WH, -FINITE] can be filled by ‘for’

Thus, the features of complementisers in English as specified (13a-d) can be summarized as in (14).

(14) (a) that = [-WH, +FINITE]

(b) for = [-WH, -FINITE]

(c) whether = [+WH, +FINITE]

(d) if = [+WH, +FINITE]

The information in (13) and (14) can be expressed in syntactic and morphological terms on the basis of which Radford (1988, p. 302) classifies complmentisers in English. On the syntactic criterion, complementisers can occur in interrogative or noninterrogative clauses and are therefore specified as [+WH]; on the morphological criterion, complementisers may serve to introduce finite or non-finite clauses and thus have the feature specification [+FINITE]. Whereas [+WH] denotes the syntactic feature of complementiser, [+FINITE] specifies their morphological feature. The classificatory and distributional information about complementisers in English shown in (13) and (14)is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Complementisers in English and their pattern of occurrence within complement clauses

3. Methodology

The data for this study were obtained from written responses (based on a free composition task designed to elicit grammaticality judgment intuition) of 420 Nigerian undergraduates(respondents) through a stratified random sampling method. The free composition task was designed to test the respondents’ most preferred choices of English complementisers and complement clause types for verb-heads in English within the range of complement clauses headed bythat,whether,orandif. The respondents were drawn from six federal universities: the University of Uyo, Uyo, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguiri,and University of Abuja, Abuja. The justification for the choice of six federal universities is based on the fact that the undergraduate population in the federal universities is representative of the ethnic nationalities in Nigeria, as well as the speakers of the various Nigerian languages. This is because the federal universities in Nigeria operate a state-bystate quota admission system which allows for admission of students in both the Sciences and Arts courses from the different ethnic nationalites (Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba, Ibibio,Edo, Izon, Tiv, etc), especially in states around where a particular federal university is located. Thus, in every federal university in Nigeria, at least six ethnic nationalities are represented.

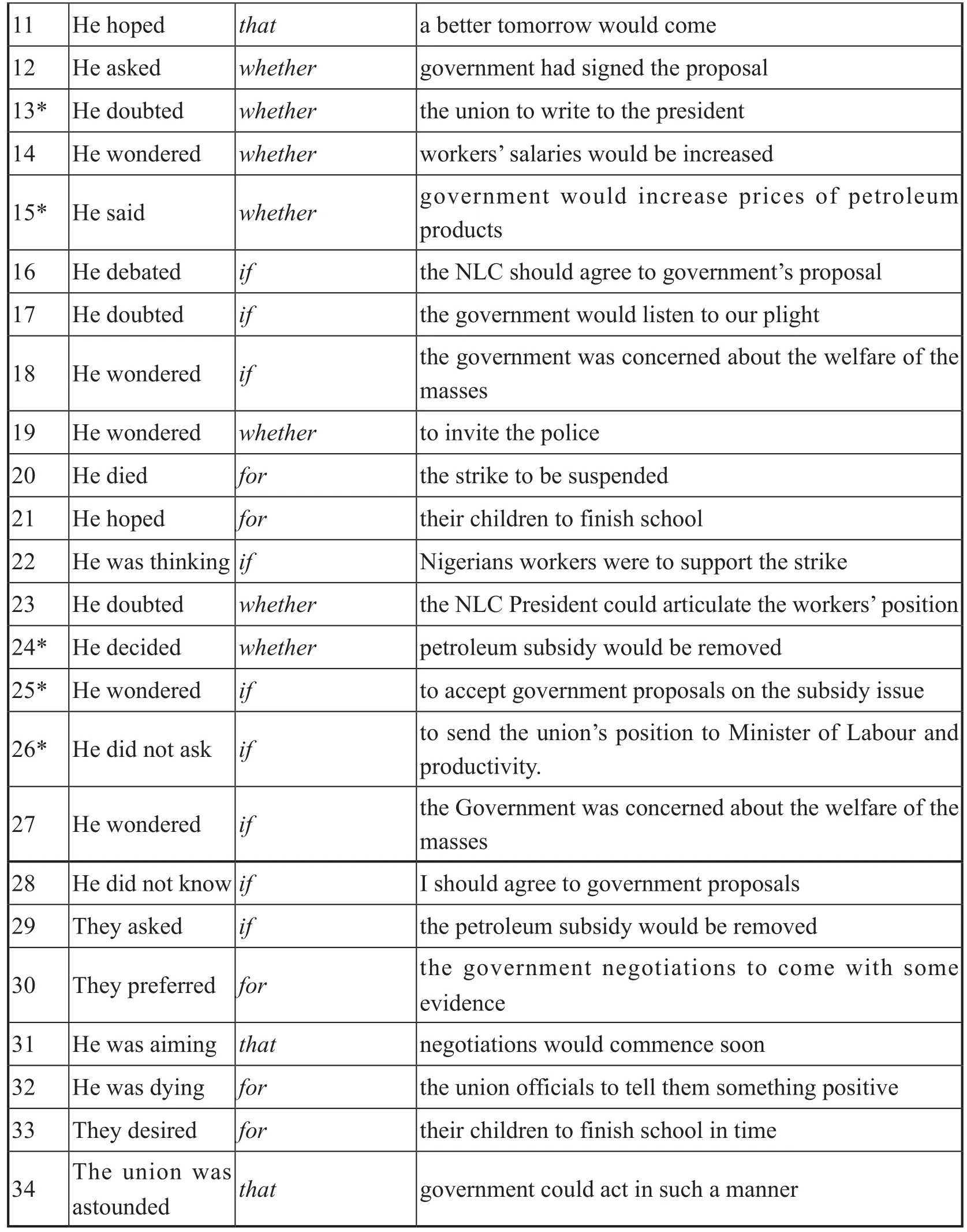

The respondents were given a written test which required them to fill out their complementiser preferences to complement clauses of certain verb-heads in English.Some of the complementiser/complement clause-types preferred by the respondents recurred both in the same respondents’ outputs as well as in the choices of other respondents. All the different complentiser choices were sorted out, analyzed, and summarized into a comprehensive list (Tables 2 and 3) .

4. Presentation and Discussion of Data

As stated earlier, data for this study were collected through a grammaticality test which was designed to determine respondents’ ability in selecting complementiser/clausal complements which are syntactically and semantically compatible with their associated V-heads. The data elicited from the respondents were analyzed and observed to feature small clauses, exceptional clauses, and ordinary clauses.The results of the study show evidence for the preference of complement clauses introduced by the complementisersthatandwhether. Thus, the complement clauses produced by the respondents featured morethatandwhetherclauses than complement clauses introduced by complementisers likeifandfor. By counting the tokens of occurrence of complemetisers and complemet clause types, and also calculating their simple percentages, it was specifically noted that the total number ofthatclauses was 128, representing 54.46% of the total number of complement clauses produced by the respondents, while the complement clauses introduced by the complementiserwhetherwas 73, representing 31.07% of the total number of complement clauses produced by the respondents. The complement clause type with the higher preference choice is described here as the “preferred choices”, while those with preference choice below 40% are, in the context of the present investigation, referred to as “l(fā)ow preferred choices”. The percentages of preferred and low preferred complement clause choices are shown in Table 2. Table 3 contains the actual instances of the complement clauses produced by the respondents.

Table 2. Preferred and low preferred complement clause choice in %

Table 3. Sample of complement clauses in the respondents’ outputs

* The asterisk is used to indicate respodents’ structures whose grammaticality statuses are in doubt.

4.1. Preference of complement clauses headed by the that-complementiser

Respondents’ verb-clause complementation responses presented in Table 3 show that different V-heads select clausal complements introduced by different complementisers(Borsely, 1991; Haegeman, 1994), since the choice of a complement by a V-head is determined largely by semantic considerations (Radford, 1997).

With respect to the choice of complement clauses, it is clear from Table 3 that the respondents showed preference for complement clauses introduced by the complementiserthat. The 54% recorded forthatclauses among the respondents may be indicative of respondents’ mind set, regardingthatas the appropriate complementiser in the particular contexts given the semantic properties of the embedding verbs as well as the morphological and syntactic properties of the complement clauses with whichthatenters into constituency.

The first five entries in Table 3 show V-heads which subcategorise for clausal complements introduced bythat. The first two entries in Table 3 feature the V-heads, ‘told’ and‘suggested’. The respondents’ use of the V-heads, ‘told’ and ‘suggested’ shows that each of them takes a nominal and a PP complement in addition to subcategorized clausal complements. It is on this criterion that the two have been analyzed as taking two complements; the nominal/PP complement and the clausal complement headed bythat.The preference ofthatclauses as complements of the V-heads ‘told’ and ‘suggested’ is consistent with the feature rules in (13) and (14). The features of the complementiserthatare [-WH] and [+FINITE], indicating that syntactically,thatusually introduces non-interrogative clausal constituents, and morphologically it occurs in complement clauses whose verbs show morphological contrasts of past and non-past tense. On the semantic dimension, the V-heads ‘told’ and ‘suggested’ are classified as ASSERTIVE predicates (Bresnan, 1970, 1979) on the basis of which each of them selects athat-clause complement (Radford, 1997) which is [+DECLARATIVE] and introduces a statementmaking clause, and not an interrogative one.

The respondents’ preference choice of thethatclause complements as shown in entries 3, 4, and 5 in Table 3, further demonstrates appropriate intuitive knowledge on the part of the respondents. The embedding verbs ‘thought’, ‘knew’ and ‘realized’ are classified semantically as COGNITIVE verbs (Bresnan, 1979), and on the basis of this semantic property, select clausal complements introduced by the complementiserthat.Each of the clauses in the entries 3, 4, and 5 in Table 3 possesses both the syntactic and the morphological features which clausal complements of the respective V-heads should select as complements. That is, the clausal constituents in entries 3, 4, and 5 are finite,non-interrogative clauses and that is why they are introduced bythat, a complementiser with the features [-WH], [+FINITE].

Similarly, entries 6, 9, 10, and 11 exemplify felicitous choices by the respondents’showing that the verbal heads ‘preferred’, ‘doubted’ and ‘hoped’ are the verbs of the respective embedded clauses as shown in entiries 6, 9, 10, and 11. The grammaticality pattern in 6-11 is explicable in terms of the fact that, generally, verbs in English impose restrictions on the complementisers which introduce the complement clauses selected to complement them. Such restrictions are in turn determined not only by syntactic and morphological considerations (see figs. 6 and 7), but also by the semantic properties which relevant heads possess, such as MANDATIVE, ASSERTIVE, COGNITIVE, etc.(Bresnan, 1979).

The embedding verb of Table 3 for entries 6 and 9 is ‘preferred’, and it is characterized semantically as a DESIDERATIVE predicate (Bresnan, 1979, p. 82). Given this semantic property, the verb ‘preferred’ can require a non-infinitival complement clause introduced by a complementiser with the features [-WH], [+FINITE], as occurred in the respondents’ output. The choice of athatclause therefore does not violate the C-selection restrictions of the verb ‘preferred’. Also due to its semantic classification as a DUBITATIVE predicate, the embedding verb in entry 10, ‘doubted’ (Bresnan,1979, p. 67) can require a complement clause introduced by a finite non-interrogative complementiser such as ‘that’ with the features [-WH], [+FINITE]. As is apparent from the data collected, an felicitous choice of the complementiserthatwas made, a choice which does not violate the C-selection principles of complement-taking predicate such as‘doubted’ (Radford, 1997).

4.2 Preference of complement clauses headed by the whether-complementiser

A 31.07% choice preference was indicated for complement clauses introduced by the complementiserwhetherin the respondents’ output. Considered against the preference forthatclauses discussed earlier (3.1), respondents’ choice preference forwhetherheaded clauses shows a 23.39% difference. This is significant since it suggests that the respondents were not aware of the linguistic fact that some complementisers possess morphological and syntactic features, which determine the range of complement clauses that they should introduce. With respect to its features, the complementiserwhetheris marked by [+WH], [+FINITE], specifying that it introduces finite interrogative complement causes in morpho-syntactic contexts. On semantic grounds(cf. Bresnan, 1979) thewhether-clause, since it is an interrogative clause itself, occurs after INTERROGATIVE and DUBITATIVE predicates. The choice of interrogative complement clauses introduced by the complementiserwhetherin Table 3, entry 12 is, therefore, consistent with the C-selection principles of the verb-head. However, an analysis of the constituent structure of the embedded clause in entry 13 shows that it is an infinitival sentence. This is signaled by the presence of the infinitival particle ‘to’,which precedes the verb ‘write’. The complementizerwhetherhas the morphological feature [+FINITE] and should introduce embedded clauses with a finite verb. This is not the case with entry 13 in Table 3. To create an appropriate morphological context for the complementiserwhether, the VP of the complement clause has to be finite so that the clause would read ‘whether the union should/could write to the president’.

Entries 14, 15, 23, and 24 also feature complement clauses introduced by the complementiserwhether. As with the embedding verbs in entries 12 and 13, the embedding verbs of the complement clauses in entries 14, 15, 23 and 24 should require complementisers with the features [+WH], [+FINITE]. It is observed from the respondents’ output that the complementiserwhetheris chosen to introduce the complement clause in entry 14. This is semantically appropriate given the classification of the embedding verb ‘wondered’ as a DUBITATIVE predicate (Bresnan, 1979, p. 82).However, the choice of awhetherclause as the clausal complement of the verb ‘said’ in entry 15 violates the C-selection principle which restricts the choice of a head’s complement to one which is semantically compatible with the head in question—in this case the embedding verb ‘said’. In the entry 15, the verb ‘said’ is characterized as an ASSERTIVE predicate, and therefore, should take athatcomplement such that the entry would be:‘said [that government will increase prices of petroleum products]sincethatis a finite non-interrogative complementiser which normally introduces statement/declarative subordinate clauses.

Respondents’ choice of the complementiserwhetheras the clause-introducer of the complement clause entry 23 of Table 3 conforms to the C-selection requirements of complement choice on the syntactic, morphological, and semantic criteria. On the syntactic criterion,whetherhas the feature [+WH] since it functions to introduce interrogative complement clauses. On the morphological criterion,whetheris marked by [+FINITE], and can therefore head finite or infinitival clauses in appropriate contexts. The embedding verb ‘decided’ in entry 24 of Table 3 is an ASSERTIVE predicate and should normally be complemented by a statement-making/declarative complement clause, and not an interrogative one as entry 24 indicates. Thus, even though the complementisersthatandwhetherhave a similar morphological feature[+FINITE], they have different syntactic features whilethatis marked for [-WH],whereaswhetheris [+WH]. The difference in syntactic marking makes respondents’preference for ‘whether’ inappropriate in the context of entry 24. The choice of awhetherclause in this instance is explicable in terms of the fact that in Englishwhether/ifare in complementary distribution tothat(Adger, 2003, p. 292): hence the difference in syntactic marking on the two complementiserswhetherandthatseems to have been blurred.

4.3 Preference of complement clauses headed by the if-complementiser

Table 3 indicates that a preferred choice of 8.94% was recorded in favour of the complementiserif, a clause-introducer, which, in contrast towhether, ‘can only introduce finite complement clauses’ (Radford, 1988, p. 302). Respondents’ choice of the complementiserifas the clause-introducer of the complement clauses ‘to accept the government’s proposals on the subsidy issue’ (entry 25) and ‘to send the union’s position to the Minister of Labour and Productivity’ (entry 26) violates C-selection restrictions on complements of V-heads on morphological grounds. As is apparent in (13a) and (14d),ifintroduces only finite subordinate clauses, hence it bears the morphological feature [+FINITE].Thus, even though the embedding verb is semantically an interrogative verb, the morphological motivation for its choice is not fulfilled in the complementation contexts under examination. The more appropriate morphological environment for the said complementiser in the two entries are shown in entries 25 and 26.

Entry 25 ... wondered [if the union can/should accept the government’s proposal on the subsidy issue]

Entry 26 … did not ask [if the union can/should send her position to the Minister of Labour and Productivity]

Entries 27, 28, and 29 demonstrate respondents’ intuitive knowledge of C-selection restrictions on the complement clause. As is evident from the data, the choice of the complementiserifsatisfies both the syntactic and the morphological requirements on complementiser choice by the V-heads. Since the complementiserifis marked by [+WH,+FINITE], it is appropriate on these two grounds to introduce the respective complement clauses in the entries. Furthermore, the embedding verbs ‘wondered’, ‘knew’ and ‘a(chǎn)sked’are DUBITATIVE, COGNITIVE, and INTERROGATIVE predicates respectively, and require anifclause complement clause since it (if) is semantically compatible with the semantic properties of the verbs.

4.4 Preference of complement clauses headed by the for-complementiser

The complementiserforrecorded the lowest preference choice among the respondents.In terms of its inherent feature,foris specified as [-WH, -FINITE], indicating that syntactically it introduces non-interrogative complement clauses and morphologically occurs in infinitival clauses. The preference score recorded for this complementiser is 5.53%, as Table 3 indicates. This low preference choice may be attributed to the fact that the respondents in this study may have associatedformore with its prepositional function than with its role as a complementiser.

In Table 3, entries 30, 32, and 33 demonstrate respondents’ familiarity with the semantic properties which V-heads ‘preferred’, ‘dying’, and ‘desired’ possess on the basis of which appropriate C-selection restrictions on complements were enforced. In entry 30, the embedding verb is ‘preferred’. Semantically, it is classified as a MANDATIVE predicate (Quirk, Leech, & Svartvik, 1985, pp. 155-157). Following this the complement clause which should complement the verb ‘preferred’ is one introduced by a noninterrogative infinitival complementiser such asfor. These requirements are met, henceforis an appropriate complementiser choice to introduce the complement clauses subcategorized for by the V-head ‘prefer’.

The C-selection conditions for the complement clause choice for entries 32 and 33 V-heads ‘dying’ and ‘desired’ are satisfied since ‘dying’ is an EMOTIVE predicate and‘desired’ a DESIDERATIVE predicate (Bresnan, 1979). The complementiserforbears syntactic and morphological features which make it semantically compatible with the V-heads. However, respondents’ preferred choice ofthatas the complement clauseintroducer in entries 31 and 34 is inconsistent with the C-selection restrictions which the V-heads in the entries under study impose on the complementiser introducing their complement clauses. The embedding V-head in entry 31 is ‘was aiming’, classified semantically as a DESIDERATIVE predicate (Bresnan, 1979). It typically takes infinitival complement clauses introduced byfor, which is inherently specified by the features: [-WH,-FINITE], and notthat,which, as has been shown earlier (3.1) introduces finite noninterrogative complement clauses.

Similarly, the verb ‘a(chǎn)stounded’ in entry 34, owing to its semantic properties as an EMOTIVE predicate (Bresnan, 1979), restricts the complementiser which should introduce its complement clause tofor, since this complementiser bears features semantically compatible with its own. We might say that the more appropriate rendering of entries 31 and 34 are as indicated below:

Entry 31 … was aiming [for negotiations to commence soon]

Entry 34 … was astounded the union [for the government to act in such a manner]

Besides the inappropriate choice of the complementiser for entries 31 and 34 V-heads,the morphological criterion is not met. The clauses in the two entries are finite clauses signaled by the presence of the modals ‘will/can’, whereasforbears the morphological feature [-FINITE].

5. Conclusion

This paper has examined complementiser and complement clause preference choice in the written English of some Nigerian undergraduates. The analyses of the data obtained from the respondents showed that both inappropriate and appropriate complement clauses choices were made. The respondents’ outputs showed a general tendency for a high preference ofthatcomplement clauses in comparison to other types of clause. It is also observed from the respondents’ choices that complementisers constitute a distinct category of items, possessing idiosyncratic morphological, syntactic and semantic features which are sensitive to the choice of the type of complement clauses they introduce. Thus, the morphological, syntactic, and semantic features of a complementiser must be compatible with the morphological, syntactic and semantic features of the complement clause with which the complementiser enters into constituency. This is also in line with the fact that selecting predicates (V-heads) may reject certain complement clauses on account of the complementiser which introduces the complement clause. The consequence of the failure in satisfying this requirement results in some of the infelicitous complement sentences found in respondents’ outputs.

Aarts, B. (2001).English syntax and argumentation(2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave Publishers.

Adesanoye, F. (1973).Varieties of written English in Nigeria(Unpublished doctoral dissertation).University of Ibadan.

Adger, D. (2003).Core syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alo, M. A., & Mesthrie, R. (2008). Nigerian English: Morphology and syntax. In R. Mesthrie (Ed.),Varieties of English 4: Africa, South and Southeast Asia(pp. 323-339). Berlin & New York:Mouton de Gruyter.

Banjo, A. (1979). Beyond intelligibility. In E. Ubahakwe (Ed.),Varieties and functions of English in Nigeria(pp. 7-13). Ibadan: African University Press.

Banjo, A. (1995). On codifying Nigerian English: Research so far. In A. Bamgbose et al. (Eds.),New Englishes: A West African perspective(pp. 203-231). Ibadan: Mosuro Publishers.

Borsely, R. D. (1991).Syntactic theory: A unified approach. London: Edward Arnold.

Bresnan, J. W. (1970). On complementisers: Towards a syntactic theory of complement types.Foundations of Language,6, 297-327.

Bresnan, J. W. (1979).Theory of complementation in English syntax. New York: Garland.

Chomsky, N. (1966).Topics in the theory of Generative Grammar. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1972).Language and mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Chomsky, N. (1981).Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Culicover, P. W. (1976).Syntax. New York: Academic Press.

Eka, D. (1979).A comparative study of Efik and English phonology(Unpublished master’s thesis).Ahmadu Bello University.

Emonds, J. E. (1976).A transformational approach to English syntax. New York: Academic Press.

Haegeman, L. (1994).Introduction to government and binding theory. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Jowit, D. (1991).Nigerian English usage: An introduction. Ibadan: Heineman.

Jubril, M. (1979). Regional variation in Nigerian spoken English. In E. Ubahakwe (Ed.),Varieties and functions of English in Nigeria(pp. 43-53). Ibadan: African University Press.

Lyons, J. (1981).Language and linguistics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moravcsik, E. (2006).An introduction to syntax: Fundamentals to syntactic analysis. London:Continuum.

Quirk, R., & Greenbaun, S. (1974).A grammar of contemporary English. London: Longman.

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1985).A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.

Radford, A. (1981).Transformational syntax: A students’ guide to Chomsky’s extended standard theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (1988).Transformational grammar: A first course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (1997).Syntactic theory and the structure of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Soames, S., & Perlmutter, D. M. (1979).Syntactic argumentation and the structure of English.Berkeley: University of California Press.

Yule, G. (2000).The study of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年4期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年4期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Developing Mathematics Games in Anaang

- Towards a Semantic Explanation for the(Un)acceptability of (Apparent) Recursive Complex Noun Phrases and Corresponding Topical Structures

- An Embodied View of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

- The Logic of Legal Narrative1

- Grammar, Multimodality and the Noun

- Remapping, Subversion, and Witnessing:On the Postmodernist Parody and Discourse Deconstruction in Marina Warner’s Indigo