Decrease in liver cancer incidence rates in Βamako, Mali over 28 years of population-based cancer registration (1987-2015)

Amina Amadou, Dominique Sighoko, Bourama Coulibaly, Cheick Traoré, Bakarou Kamaté, Brahima S Mallé,Ma?lle de Seze, Francine N Kemayou Yoghoum, Sandrine Biyogo Bi Eyang, Denis Bourgeois, Maria Paula Curado, Siné Bayo, Emmanuelle Gormally, Pierre Hainaut

Amina Amadou, Institute for Advanced Biosciences, Grenoble 38700, France

Amina Amadou, Department of Prevention Cancer Environment, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon 69008, France

Dominique Sighoko, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60611, United States

Βourama Coulibaly, Cheick Traoré, Βakarou Kamaté, Βrahima S Mallé, Francine N Kemayou Yoghoum, Sandrine Βiyogo Βi Eyang, Siné Βayo, Department of Pathological Anatomy and Cytology, University Hospital of Point G, Bamako BP333, Mali

Ma?lle de Seze, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris 75005, France

Denis Βourgeois, Health, Systemic, Process, UR 4129 Research Unit, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Villeurbanne 69100, France

Maria Paula Curado, Epidemiology and Statistics Nucleus, ACCamargo Cancer Center, Sao Paulo 01508-010, Brazil

Emmanuelle Gormally, Sciences and Humanities Confluence Research Center, Université Catholique de Lyon, Lyon 69288, France

Pierre Hainaut, Institut pour l’Avancée des Biosciences, Grenoble 38700, France

Abstract BACKGROUND Primary liver cancer is common in West Africa due to endemic risk factors. However, epidemiological studies of the global burden and trends of liver cancer are limited. We report changes in trends of the incidence of liver cancer over a period of 28 years using the population-based cancer registry of Bamako, Mali.AIM To assess the trends and patterns of liver cancer by gender and age groups by analyzing the cancer registration data accumulated over 28 years (1987-2015) of activity of the population-based registry of the Bamako district.METHODS Data obtained since the inception of the registry in 1987 through 2015 were stratified into three periods (1987-1996, 1997-2006, and 2007-2015). Age-standardized rates were estimated by direct standardization using the world population. Incidence rate ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using the early period as the reference (1987-1996). Joinpoint regression models were used to assess the annual percentage change and highlight trends over the entire period (from 1987 to 2015).RESULTS Among males, the age-standardized incidence rates significantly decreased from 19.41 (1987-1996) to 13.12 (1997-2006) to 8.15 (2007-2015) per 105 person-years. The incidence rate ratio over 28 years was 0.42 (95%CI: 0.34-0.50), and the annual percentage change was -4.59 [95%CI: (-6.4)-(-2.7)]. Among females, rates dropped continuously from 7.02 (1987-1996) to 2.57 (2007-2015) per 105 person-years, with an incidence rate ratio of 0.37 (95%CI: 0.28-0.45) and an annual percentage change of -5.63 [95%CI: (-8.9)-(-2.3)].CONCLUSION The population-based registration showed that the incidence of primary liver cancer has steadily decreased in the Bamako district over 28 years. This trend does not appear to result from biases or changes in registration practices. This is the first report of such a decrease in an area of high incidence of liver cancer in Africa. This decrease may be explained by the changes and diversity of diet that could reduce exposure to aflatoxins through dietary contamination in this population.

Key Words: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Hepatitis B infection; Aflatoxin; West Africa; Cancer registration; Annual percentage change

lNTRODUCTlON

Evidence shows that global trends of the incidence of primary liver cancer are undergoing contrasting changes in different parts of the world[1-5]. Primary liver cancer includes hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and several rare forms of mesenchymal or lymphoid origin. Globally, HCC is by far the most common diagnosed liver cancer, representing 80%-90% of the cases in most regions, with the exception of defined regions of Southeast Asia where intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is predominant owing to infections by endemic liver flukes. Analysis of cancer registration data collected by Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC, CI5V-XI, and CI5plus) and the NORDCAN database revealed that the incidence of liver cancer between 1978 and 2012 in high-risk countries, mostly in Eastern and Southeastern Asia, remained high but decreased for the most recent period. In contrast, in low-risk countries, such as India and some countries in Europe, America, and Oceania, the incidence rate is rising[4].

A projection of the future burden of liver cancer in 2030 in 30 countries predicts an increase in the incidence rates in most countries, with the exception of some Asian countries (China, Japan, and Singapore) and European countries (Estonia, Czech Republic, and Slovakia) where declines in rates are foreseen[3,5]. Liver incidence rates in sub-Saharan Africa are high though data are scarce. Africans are more likely to develop liver cancer at a younger age and to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, resulting in poorer outcomes than in patients from countries with a high development index[6-9].

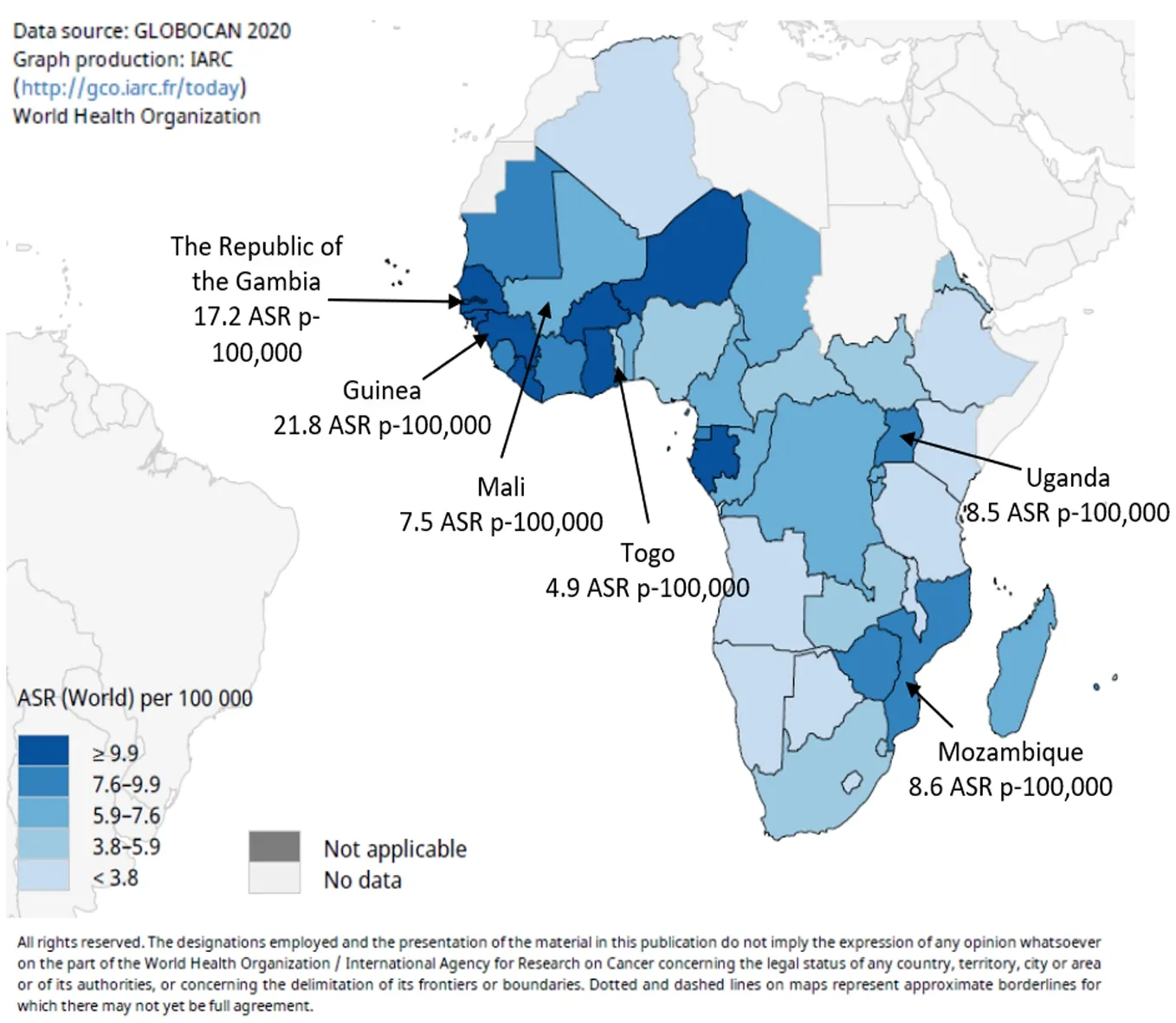

Worldwide, primary liver cancers are mostly HCC (> 90%)[10], and in West Africa it is the most fatal malignancy in males and the third most fatal malignancy in females[11]. The main risk factor is the synergistic effect of chronic infection by hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is endemic in these populations, and dietary exposure to the carcinogenic mycotoxin aflatoxin, a widespread contaminant of traditional diets[12-16]. In 2020 in West Africa, age-standardized rates (ASR) for liver cancer were estimated to range between 21.8 (Guinea) and 4.9 (Togo) ASR p-100000 persons[17,18] (Figure 1; https://gco.iarc.fr/). Recent changes in dietary patterns and lifestyles, in awareness and prevention of the main risk factors, and the introduction of neonatal and infant vaccination against HBV are raising expectations that the incidence of chronic liver diseases and liver cancer may significantly decrease in the coming years[9].

Figure 1 Estimated age-standardized rates (world) in 2020 for liver cancer in both sexes of all ages[17,18]. Figure produced with the help of the Global Cancer Observatory web site (International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, http://gco.iarc.fr/today). ASR: Age-standardized rates.

However, until now, the only two studies on trends of liver cancer in sub-Saharan Africa, in Uganda (Kyadondo) and in the Gambia have observed a relative stability or only a limited decrease in incidence rates among males, whereas among females a significant increase was observed[19,20]. Understanding the reasons for these variations is crucial for the correct interpretation of ongoing changes in the prevalence and population impact of the main risk factors for liver cancer in this region.

Population-based cancer registration is limited in Africa. Maintaining a registry in a low-resource context is complex from an operational viewpoint. Furthermore, variations in clinical procedures, in patterns of patient referral, and in diagnostic practices are often insufficiently documented, making it difficult to distinguish between biological effects and cancer registration biases when analyzing observed variations in incidence. Mali (Bamako district, also covering the city of Kati) and the Gambia (National cancer registry) are among the rare countries of the sub-region of West Africa to have operational population-based cancer registries. In this study, we have used cancer registration data accumulated over 28 years of activity of the population-based registry of the Bamako district to assess the trends and patterns of liver cancer by sex and age-groups.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study population

Cancer data from 1987 to 2015 of the cancer registry of the Bamako district, Mali were used. Mali (surface area: 1246238 km2) had an estimated population of 18343000 in 2016, with life expectancy of 60 years for females and 59 years for males[21]. Bamako district, the capital city, had a population estimated at 2529328 in 2019[22]. Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. It has few resources for health care, and child and infant mortality rates are among the highest in the world. Education services are poorly developed, particularly at the primary level and in rural areas. The expected years of schooling in 2019 was 7.5 years. Despite improvements in medical care, Mali is still challenged by a lack of personnel, facilities, resources, and supplies. However, over the past 20 years, Mali has defined several policies that have served as a reference framework for all social and health development programs in order to strengthen the health system, to provide equitable access to health care, and to prevent, detect, and respond effectively to epidemics and public health emergencies[23,24].

The healthcare system in Mali comprises local community health centers delivering primary health care, secondary referral centers, six of which are located in the Bamako district and which provide specialized care in, among others, gynecology and obstetrics, general surgery, pediatrics, stomatology, and oto-rhino-laryngology, and tertiary referral centers represented by the three university hospitals of Mali, namely the hospitals of Point G and Gabriel Touré (both localized in Bamako city) and of Kati (15 km southeast of Bamako).

On behalf of the ministry of health, the regional cancer registry for the Bamako district created in 1987 was used to support cancer surveillance activities. It is an official authoritative source of information on cancer incidence and survival in Mali. Relevant policies, regulations, and laws are strictly implemented to guide the handling of information in cancer registries. These procedures protect the confidentiality and privacy of both cancer patients and healthcare professionals. After declassifying the patient information, with no identifiers for cancer patients, the regional cancer registry provides access to the data for researchers in the form of databases. This registry records information on cancer cases from all possible sources within the district of Bamako. Every month an active collection of all cases diagnosed in all medical services (public or private) in the Bamako district is recorded. Information is collected through pathology files, patient clinical files, hospital-based registries (such as chemotherapy, endoscopy, and surgery registries), and through death certificates managed by a non-governmental Malian organization, the Center for Information, Counselling, Care and Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS. After collection, all data are computerized using the software CanReg 4[25]. Tumors are coded according to the ICD-O third edition.

Patients who were resident from locations outside of the Bamako district were excluded from the incidence data analyses. Bamako residents are defined as being in residence for the previous 3 mo in the district[26]. Demographic data for Bamako district in person-years (p-years) from 1987 to 2015 were obtained by the interpolation of data extracted from the national censuses of 1976, 1998, and 2009.

Statistical analysis and data modelling

ASRs were estimated by direct standardization, with rates adjusted to the world population by 5-year age groups. Incidence data were calculated for three arbitrarily defined periods: 1987-1996, 1997-2006, and 2007-2015. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the early period as reference (1987-1996), using STATA software version 14 (College Station, TX, United States). Temporal trends over the whole period of 28 years were assessed using Joinpoint regression analyses [program version 3.3 (https://www.cancer.gov/joinpoint)]. Data for the year 2005 were excluded because of an apparent unexplained registration bias.

Liver cancer cases diagnosed by endoscopy were further excluded to avoid potential overestimation of liver cancer cases since endoscopy is not one of the standard methods for liver cancer diagnosis. As for most parts of Africa, Mali and the Bamako district have a population structure characterized by a strong representation of younger age groups, with only 2.5% of the population aged 65 years and over. This distribution causes a bias when evaluating incidence rates in the older age groups because of the small population denominators. Therefore, instead of expressing the age-specific rates per 100000, we modelled the expected number of cases in a standard population in which the age-specific rate is adjusted to the world standard population[27]. This approach minimizes the tendency to overestimate cancer incidence in older age groups and thus provides a more accurate picture of the distribution of common cancers across the different age groups. For the sake of comparison with liver cancer, we additionally analyzed the most frequent cancers (breast, bladder, stomach, prostate, and cervix uteri). All statistical tests were two-sided, andPvalues < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the cancer cases and liver diagnostic criteria

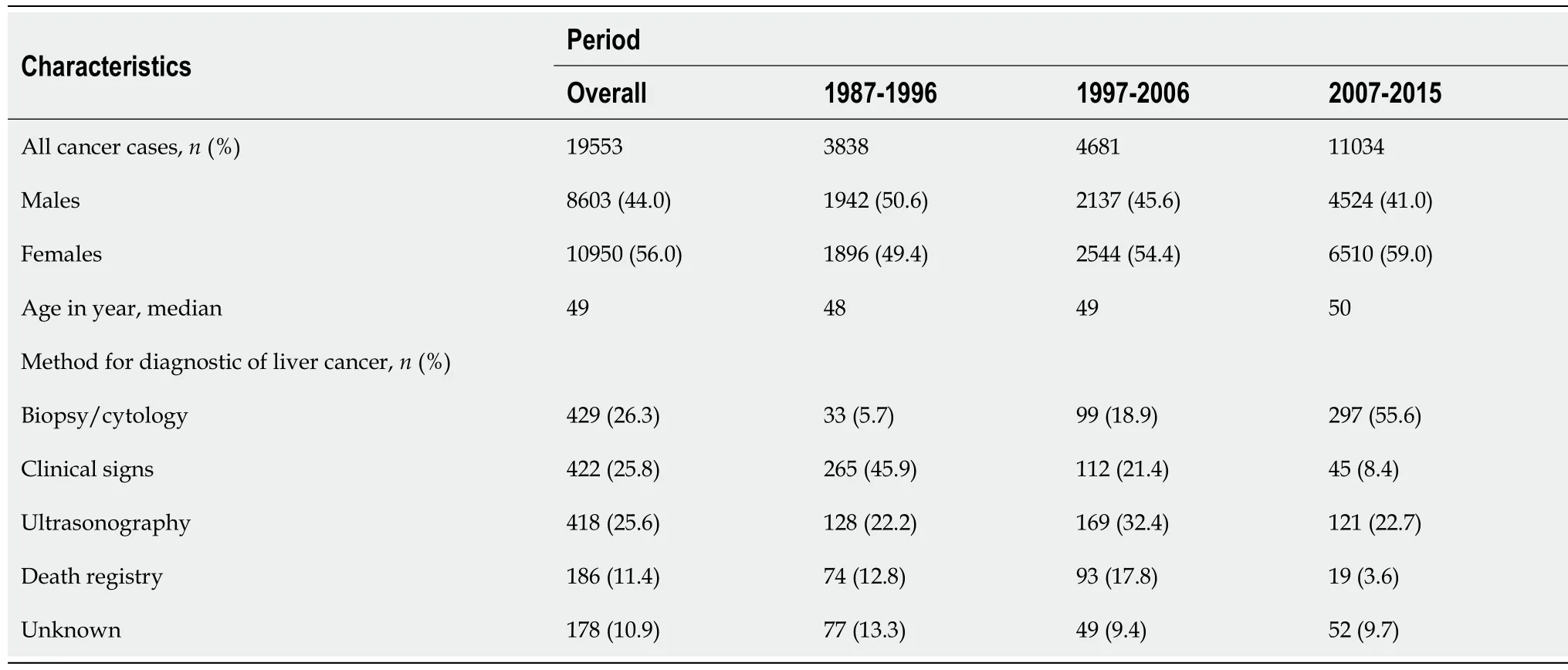

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study subjects for all cancers and according to the three periods of diagnosis. From 1987 to 2015, the cancer registry of Bamako, Mali registered 19553 cancer cases including 8553 (44.0%) in males and 10950 (56.0%) in females. The median age of the study subjects at the time of cancer diagnosis was 49 years. Overall, diagnosis of all cancers was based on histopathology for 58.2% of the cases in males and 70.2% in females, with an increase in this trend over the years.

Table 1 Characteristics of the cancer cases overall and according to the three periods of cancer diagnosis from the cancer registry of Βamako, Mali

There were 634 primary liver cancer cases (11.2% of the total cases) after exclusion of those diagnosed by endoscopy. The diagnosis of primary liver cancer mainly relied on the biopsy/cytology (26.3%), the classical triad of clinical signs (hepatomegaly, icterus, and ascites) (25.8%), and ultrasonography (25.6%). Diagnosis based on biopsy/cytology increased from 5.7% in the earlier period (1987-1996) to 55.6% in the later period (2007-2015), whereas diagnosis based only on clinical signs decreased from 45.9% in the earlier period (1987-1996) to 8.4% in the later period (2007-2015). A review of clinical bases of diagnoses at the two tertiary referral centers of Bamako city (Hospital Gabriel Touré; Department of Gastroenterology and Point G Hospital; Department of Internal Medicine) indicated that the most common clinical signs were hepatomegaly and icterus and the presence of ascites, and the main symptoms were pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. Alpha-fetoprotein levels were ≥ 400 ng/mL in 45.0% of the cases.

Incidence rates and trends of liver cancer

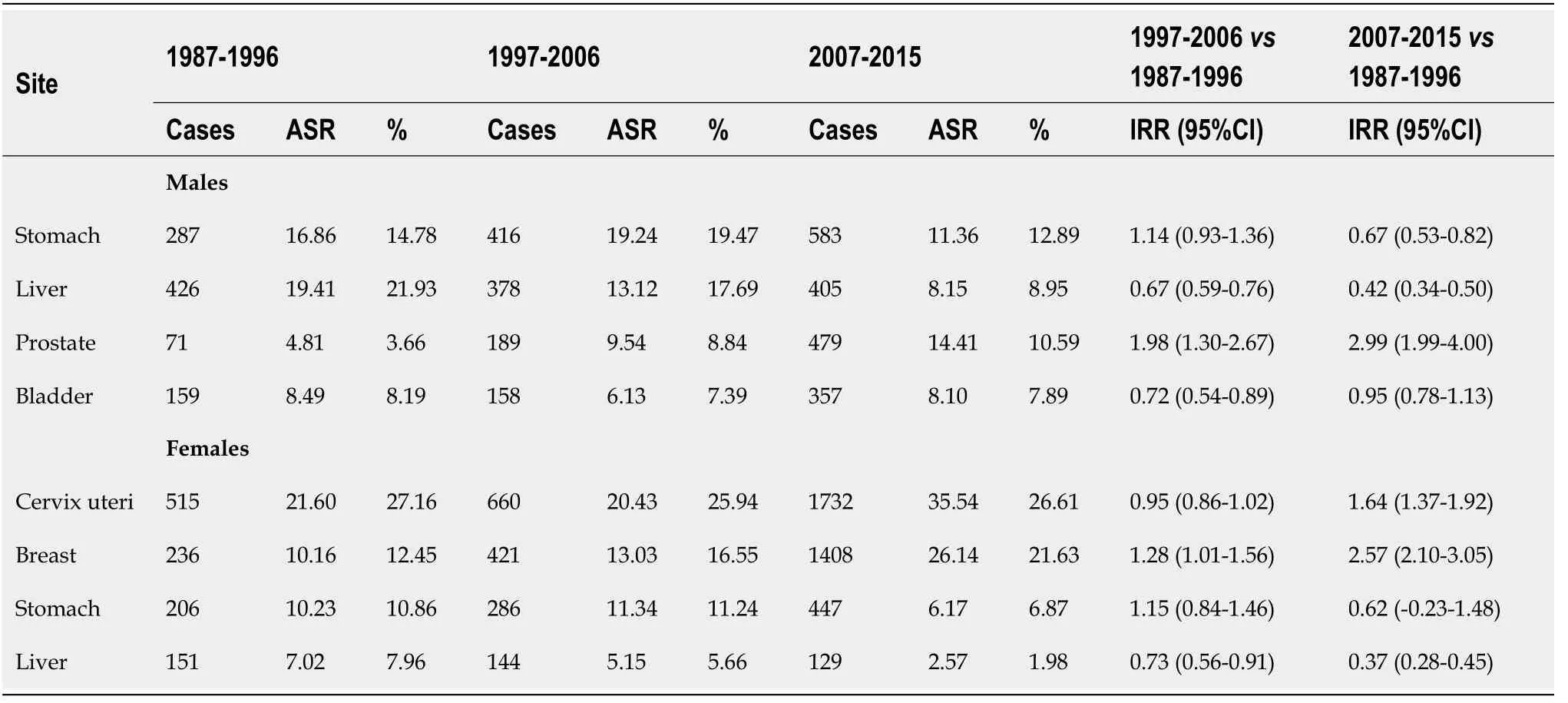

Table 2 compares the incidence of the four most common cancers among males and females over the three periods. These cancers are liver, stomach, bladder, and prostate in males and liver, stomach, cervix uteri, and breast in females. In males, a total of 426 cases of liver cancers were diagnosed during the early period (1987-1996), representing 21.93% of all cancers compared to 378 cases in the middle period (1997-2006) (17.69%) and 405 cases in the later period (2007-2015) (8.95%). In females, the total number of liver cases diagnosed in the early period (1987-1996) was 151 (7.96% of all cancers) compared to 144 (5.66%) in the middle period (1997-2006) and 129 cases (1.98%) in the later period (2007-2015).

ASR for liver cancer significantly decreased over the three periods in both sexes. For males, rates dropped from 19.41 per 105p-years for the period 1987-1996 to 13.12 for the period 1997-2006 [33% decrease; IRR: 0.67 (95%CI: 0.59-0.76)] and 8.15 for the period 2007-2015 [58% decrease over period 1987-1996; IRR: 0.42 (95%CI: 0.34-0.50)]. Among females, rates decreased from 7.02 per 105p-years for the period 1987-1996 to 5.15 in the period 1997-2006 [27% decrease; IRR: 0.73 (95%CI: 0.56-0.91)] and 2.57 for the 2007-2015, representing a decrease of 63% compared to the period 1987-1996 [IRR: 0.37 (95%CI: 0.28-0.45)] (Table 2).

It is noteworthy that variations in incidence were also observed for several other common cancers in males and females over the entire registration period (Table 2). Namely, a significant increase was observed for prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. When comparing earlier (1987-1996) and later (2007-2015) periods, incidence rates of prostate and breast cancers increased by 2.57 and 2.99-fold, respectively. In contrast, rates of bladder cancer remained stable in males, whereas rates of stomach cancer showed a decrease of 33.0% and 38.0% in males and females, respectively.

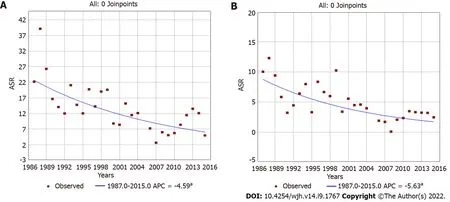

Trend analyses of liver cancer covering the 28 years of registration data (encompassing the three periods) showed that incidence rates steadily and progressively declined in both sexes. The annual percentage change was -4.59 [95%CI: (-6.4)-(-2.7)] in males (Figure 2A) and -5.63 [95%CI: (-8.9)-(-2.3)] in females (Figure 2B). When analyzing age specific curves, we observed that for the three periods and for both sexes, curves were similar and showed peaks in approximately the same age group (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2).

Table 2 Comparison of the incidence (age-standardized rate) of the four most common cancers among males and females over three periods in Βamako, Mali from the cancer registry of Βamako)

Figure 2 Liver cancer incidence (age-standardized rate) trends over 28 years of cancer registration data in Βamako, Mali. aIndicates that the Annual Percent Change is significantly different from zero at the alpha = 0.05 level. Final Selected Model: 0 Joinpoints. A: Male; B: Female. ASR: Age-standardized rates.

DlSCUSSlON

In this study, we have analyzed data from the population-based cancer registry covering the district of Bamako over 28 years of registration (1987-2015) to assess trends in the incidence of liver cancer, one of the most common forms of cancer in the West African population. We have compared incidence rates over three defined periods, 1987-1996, 1997-2006, and 2007-2015. Over these periods, liver cancer showed a remarkable and progressive decrease in the ASR in both genders and in all age groups, with a significant annual percentage change of -4.59 among males and of -5.63 among females. Such a large reduction in incidence rate was not observed for other common cancers in the adult population of the district of Bamako. Notably, over the entire registration period, incidence rates for breast and prostate cancers significantly increased, a trend also observed in other West African countries[27,28] as well as globally in low-resource countries[29].

Factors such as westernized diet, urbanization, increasing awareness, and improved registration and diagnosis have been implicated, although their precise specific contributions are yet to be fully established. In Mali, the fact that only liver cancer showed a strong and systematic decrease in incidence rate suggests that the decrease is not a bias caused by changes or discontinuity in cancer diagnosis or registration practices. A review of clinical practices indicated that clinical diagnosis and main symptoms for liver cancer have remained stable over the entire study period (28 years). Of note, the proportion of patients who received confirmation based on biopsy/cytology analysis substantially increased from 5.7% in 1987-1996 to 55.6% in 2007-2015. However, there is no evidence that the absence of biopsy/cytology analysis has been used as a criteria to exclude patients from registration. In this respect, it should be noted that registration for other cancers (stomach, prostate, bladder, cervix, and breast) did not show such an important decrease despite increased usage of biopsy/cytology analysis in diagnosis. Therefore, we suggest that increased usage of microscopy as a diagnostic tool cannot be considered as the main explanation for the observed decrease in liver cancer incidence.

Trends in liver cancer incidence rates show contrasting patterns across the world. In an analysis of the data collected between 1978 and 2012 from 42 countries worldwide (registry data from CI5 volumes VXI, CIplus and NORDOCAN database), Petricket al[4] found that incidence rates significantly increased in India, across the Americas, in Oceania, and in most European countries. On the other hand, incidence rates remained the highest in Eastern and Southeastern Asian countries, though the rates in those countries have been decreasing in recent years.

In the area of Qidong city, Eastern China, a dramatic reduction of liver cancer incidence has been seen in young adults over a period of 28 years (1980-2008)[30]. Qidong city is known as an area of very high liver cancer incidence associated with endemic HBV and high dietary exposure to aflatoxin. Overall, a 45% reduction in liver cancer incidence and mortality rates occurred among the Qidonese. Compared with 1980-1983, the age-specific liver cancer incidence rates in 2005-2008 significantly decreased 14-fold for ages 20-24, 9-fold for ages 25-29, 4-fold for ages 30-34, 1.5-fold for ages 35-39, 1.2-fold for ages 40-44, and 1.4-fold for ages 45-49 but increased at older ages[30]. Etiological interventions aimed at reducing risk factors for HBV have been developed in this area of China since the early 1980s, namely universal neonatal HBV vaccination (from 1980) and expanded access to commercial rice (controlled for low aflatoxin levels) instead of contaminated maize as the staple food (beginning in 1988).

Retrospective studies on the distribution of aflatoxin-albumin adducts in randomly selected subsets of serum collected during screening surveys between 1982 and 2009 revealed that median levels declined from 19.3 pg/mg albumin in 1989 to 3.6 pg/mg in 1995, 2.3 in 1999, 1.4 pg/mg in 2003, and undetectable (< 0.5 pg/mg) in 2009[31]. These results suggest that the dramatic decrease in incidence in this population is most likely due to reduction in aflatoxin exposure, whereas neonatal HBV vaccination may only have a limited impact since the vast majority of the subjects developing liver cancer during the period under consideration (1983-2008) were born before the start of universal HBV vaccination programs[30,31].

Available data on population-based cancer registries in Africa that have assessed liver cancer trends over a comparable period of time show a very different pattern to the one observed in Bamako, Mali. In the Gambia, a study on liver cancer trends from 1988 to 2006 has shown a small decrease among males during the period 1988-2006 (from 38.36 for the period 1988-1997 to 32.84 per 105p-years in the period 1998-2006), while it clearly increased among females (from 11.71 for the period 1988-1997 to 14.9 p-years in the period 1998-2006) [annual percentage change: +3.01 (95%CI: 0.3-5.8)][20]. In the district of Kampala, Uganda, registration was initiated in 1960 but was interrupted between 1980 and 1991 due to the political context. The comparison between the periods before 1980 and after 1991 showed stability in the rate of liver cancer among males and an increase of more than 50% among females[19]. A reduction in the rate of liver cancer has been documented in a group of gold miners originating from Mozambique and working in South Africa. In this group, liver cancer incidence decreased from 80.4 per 105p-years in 1964-1971 to 40.8 in 1972-1979 and 29.9 per 105p-years in 1981[32,33]. However, in this later cohort, data were not population-based. To our knowledge, our observation of a dramatic decrease in the incidence of liver cancer in Bamako, Mali is not matched in any other African context.

Our observations based on the cancer registry of the Bamako district require cautious interpretation because of multiple possible bias that may affect cancer registration in low-resource contexts. A recent review of trends in the global epidemiology of liver cancer has highlighted the lack of data of sufficient quality in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa[4]. As underlined in our study, increased usage of biopsy/cytology confirmation has taken place over the study period and may have led to underregistration of cases for which this confirmation was not available. With all due caution, however, we consider that our observations on liver cancer in the Bamako district deserve to be documented in the literature. Of note, stomach cancer, which shares demographic and clinical signs that overlap with liver cancer (age-related incidence rates, signs and symptoms, and sex distribution) showed only small changes in incidence in the Bamako district during the study period[27]. Patients with stomach cancer are often diagnosed in the same medical services as those with liver cancer, and it could be expected that biases may equally affect the registration of both cancers.

In Qidong city, the liver cancer decrease was mainly due to a reduction in aflatoxin exposure[31]. In Mali, there is only limited information available on temporal variations in the prevalence of the main documented risk factors for HCC, namely chronic infection by HBV and exposure to dietary aflatoxins. A study of HBV chronic carriers in Bamako indicated that the incidence rate of chronic carriers was 18.8%[16]. There is no evidence that this rate has recently decreased. Universal infant HBV vaccination was introduced in Mali in 2002 and is unlikely to have a significant effect on the circulation of HBV and on population rates of chronic carriers in the target age groups for liver cancer before at least one decade.

The presence of aflatoxin in peanuts (groundnuts) and their derived products at several points of the food supply chain from cultivation to marketing have been documented in several small surveys carried out in different parts of the peanut production area (Southern Mali)[34-36]. A survey conducted in public markets of Kita, Kolokani, and Kayes collected peanuts and peanut pastes over 7 mo between 2010 and 2011 from 30 different small retailers in each location. In these samples, contamination with aflatoxin was found to be above the permissible range (> 20 μg/kg) and ranged between 105 and 530.2 μg/kg. The level of aflatoxin was higher in peanut pastes and increased with the length of storage at the level of the small retailers, indicating that post-harvest contamination increased during storage[36].

Despite the continuous presence of aflatoxin as a food contaminant, it is possible that actual levels of individual exposure in the Bamako district have decreased over the past years. Several reasons could potentially explain the decrease in the incidence of liver cancer in the population of Bamako. First, changes in lifestyle and diversification of diet may have led to a decrease of the proportion of locally produced aflatoxin-contaminated products in the daily food intake. Indeed, a study exploring the association between the food variety score, dietary diversity score and nutritional status of children, and socioeconomic status level of the household has shown that children from the urban area in Mali have more dietary diversity than children from rural areas[37]. This study also reported that the food variety and dietary diversity in urban households with the lowest socioeconomic status were higher than the one found among rural households with the highest socioeconomic status[37].

Second, the systematic implementation of effective measures for reducing aflatoxin levels in crops in villages across the peanut production area has led to a measurable reduction in aflatoxin levels documented in several local surveys[35,36]. These measures include pre- and post-harvest management options such as selection of host plant resistance, soil amendments, timely harvesting and postharvest drying methods, use of antagonistic biocontrol agents, and awareness campaigns, as well as training courses to disseminate technology to the end-users[35].

A study conducted in Bamako in chronic HBV carriers suggested that overall these carriers were exposed to aflatoxin to a lesser extent than HBV carriers from rural Gambia[16]. In this study, the mutant R249S of theTP53gene, a mutation specific to aflatoxin exposure, was used as a surrogate to measure levels of exposure to aflatoxin. In Bamako, HBV carriers had an average plasma concentration of R249S of 311 copies/mL, while in rural areas of the Gambia the concentration varied between 480 to 5690 copies/mL. These data corroborate the idea that aflatoxin levels have reduced in the staple diet of people living in Bamako. Whether a decrease in exposure to aflatoxin is the cause of the decrease in incidence of liver cancer is a tantalizing hypothesis that may have a profound impact for promoting further efforts to reduce population exposure.

Further assessment of a possible effect of decreased aflatoxin intake will require detailed studies on biomarkers of exposure as well as comparison between the urban area of Bamako and rural areas of Mali and other West African countries where contaminated peanuts may still represent a major part of the diet. The data presented here warrant further studies to uncover the sociocultural and biological changes that have occurred over the study period and might explain the decrease in liver cancer reported in this article.

CONCLUSlON

In conclusion, this study reported a dramatic decrease in the registration of primary liver cancer over 28 years in an urban population of West Africa. This decrease cannot be accounted for by universal childhood HBV vaccination, which was only introduced recently (2002). There is evidence that reduction of exposure to aflatoxin has occurred over the study period, caused by changing lifestyle and dietary patterns in this population. This suggests that controlled reduction of aflatoxin may achieve rapid and important protective effects against liver cancer in West Africa. However, our observations require cautious interpretation because of possible bias that might affect liver cancer registration in this low-resource context.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

There is evidence that trends in the incidence of liver cancer in different parts of the world are undergoing contrasting changes.

Research motivation

There is very little data on liver cancer incidence trends in sub-Saharan Africa.

Research objectives

Using the cancer registry of the Bamako district, Mali, we have studied incidence trends of liver cancer over 28 years (from 1987 to 2015) by sex.

Research methods

Age-standardized rates were estimated using a direct standardization method by considering the world population. The incidence rate ratio and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the early period as reference (1987-1996). The average annual percent change of the trends was evaluated from Joinpoint regression models.

Research results

Overall, the age-standardized incidence of liver cancer varied substantially across the three periods of the study. There was a significant decrease of liver cancer incidence over the study period in males and females.

Research conclusions

This study showed a decrease in the registration of primary liver cancer in an urban population of West Africa between 1987 and 2015. Lifestyle changes and diversification of diet may have led to a decrease in exposure to aflatoxin-contaminated products.

Research perspectives

Future studies are warranted to explore the potential reasons for this decrease in order to better understand the specific etiological factors of liver cancer in West Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to sincerely thank Dr Philippe Autier for critical review and thoughtful comments on this manuscript and Dr Philip Lawrence for careful proofreading of the manuscript.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Amadou A, Sighoko D, Hainaut P, and Gormally E designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; Coulibaly B, Traoré C, Kamaté B, Mallé BS, Kemayou Yoghoum FN, Biyogo Bi Eyang S, and Bayo S contributed to the collection of the data; de Seze M, Bourgeois D, and Curado MP analyzed the data; and all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

lnstitutional review board statement:On behalf of the ministry of health, the regional cancer registry for Bamako district was used to support cancer surveillance activities. It is an official authoritative source of information on cancer incidence and survival in Mali. Relevant policies, regulations, and laws are strictly implemented to guide the handling of information in cancer registries. These procedures protect the confidentiality and privacy of both cancer patients and healthcare professionals. After declassifying the patient information, with no identifiers for cancer patients, the regional cancer registry provides access to the data for researchers in the form of databases.

lnformed consent statement:The informed consent was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Data from the cancer registry of Bamako, Mali are available on demand from the cancer registry.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:France

ORClD number:Amina Amadou 0000-0001-6662-2089; Dominique Sighoko 0000-0003-2724-9634; Denis Bourgeois 0000-0003-4754-2512; Maria Paula Curado 0000-0001-8172-2483; Emmanuelle Gormally 0000-0001-7061-0937; Pierre Hainaut 0000-0002-1303-1610.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Hepatology2022年9期

World Journal of Hepatology2022年9期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Analysis of hepatitis C virus-positive organs in liver transplantation.

- Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review

- A retrospective study on use of palliative care for patients with alcohol related end stage liver disease in United States

- Hereditary hemochromatosis: Temporal trends, sociodemographic characteristics, and independent risk factor of hepatocellular cancer- nationwide population-based study

- Liver magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of response to treatment after stereotactic body radiation therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Modified preoperative score to predict disease-free survival for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with surgical resections