Practical review for diagnosis and clinical management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma

Daniele Dondossola, Michele Ghidini, Francesco Grossi, Giorgio Rossi, Diego Foschi

Abstract Cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) is the most aggressive malignant tumor of the biliary tract. Perihilar CCC (pCCC) is the most common CCC and is burdened by a complicated diagnostic iter and its anatomical location makes surgical approach burden by poor results. Besides its clinical presentation, a multimodal diagnostic approach should be carried on by a tertiary specialized center to avoid missdiagnosis. Preoperative staging must consider the extent of liver resection to avoid post-surgical hepatic failure. During staging iter, magnetic resonance can obtain satisfactory cholangiographic images, while invasive techniques should be used if bile duct samples are needed. Consistently, to improve diagnostic potential, bile duct drainage is not necessary in jaundice, while it is indicated in refractory cholangitis or when liver hypertrophy is needed. Once resecability criteria are identified, the extent of liver resection is secondary to the longitudinal spread of CCC. While in the past type IV pCCC was not considered resectable, some authors reported good results after their treatment. Conversely, in selected unresectable cases, liver transplantation could be a valuable option. Adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for resected patients, while neoadjuvant approach has growing evidences. If curative resection is not achieved, radiotherapy can be added to chemotherapy. This multistep curative iter must be carried on in specialized centers. Hence, the aim of this review is to highlight the main steps and pitfalls of the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to pCCC with a peculiar attention to type IV pCCC.

Key words: Perihilar cholangiocarncioma; Liver resection; Biliary drainage; Neo-adjuvant therapy; Type IV cholangiocarcinoma; Klatskin tumor

INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) is the most frequent and aggressive malignant tumor of the biliary tract. It arises from the epithelial cells of a bile duct and from their progenitor cells (a group of heterogeneous dynamic cells lining the biliary tree). CCC develops either within the duct or shaping a mass infiltrating the adjacent tissue (mass forming cholangiocarcinoma)[1].

CCC is commonly classified according to the site of invasion into intrahepatic and extrahepatic, itself divided into hilar/perihilar [or Klatskin tumor, perihilar CCC (pCCC)] and distal. Extrahepatic CCC are the most common among CCC[2]. pCCC is defined as CCC located in the extrahepatic biliary tree proximal to the origin of the cystic duct[3,4]. It is burdened by a complicated diagnostic iter and its anatomical location makes the surgical site less accessible, causing higher unresectable rates[5].

In this review, we will focus our attention on diagnostic and surgical approach to pCCC in order to underline the key points in its management.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOPATHOGENESIS

CCC is a heterogeneous group of malignancies that represent the 3% of all gastrointestinal tumors[6]. Among CCC, 75% are extrahepatic CCC and half of them pCCC. The incidence of extrahepatic CCC varies worldwide from 0.3-3.5 per 100000 inhabitants/year in North America to 90/100000 inhabitants/year in Thailand. Among Mediterranean region, the incidence is fixed around 7.5/10000 inhabitants/year[7,8]. In Italy 5400 new cases/year are expected[9]. Extrahepatic CCC represent 1% of new neoplastic diagnosis in male and 1.4% in female, with a reduction in the female sex during the last few years[10]. The median age at diagnosis is 50 years; almost null risk is reported before 40 years, while a peak is registered around 70 years[9].

The identification of risk factors for pCCC is some-like difficult due to many reasons; first of all, papers do not often distinguish CCC into intrahepatic or extrahepatic and merge CCC with gallbladder carcinomas. Furthermore, cases are frequently isolated with no identifiable risk factors. The published risk factors can be divided in[11,12]: Known: Hepato/choledocholithiasis, hepatitis B and C infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, congenital hepatic fibrosis, Caroli’s disease or choledocal cyst, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), liver fluke infections (Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis), intrahepatic litiasis and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis; suspect: Inflammatory bowel disease, smoke, asbestos, genetic polymorphisms, diabetes.

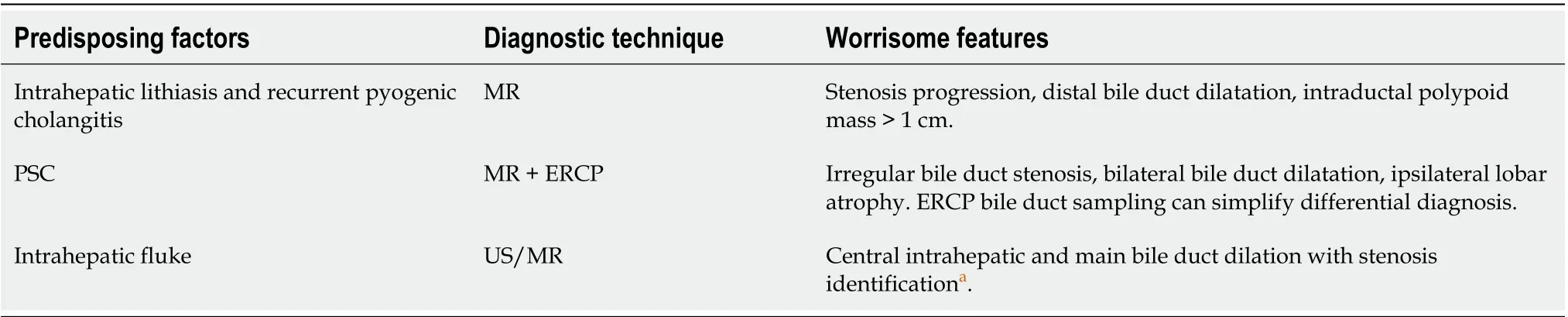

According to these data, a surveillance program can be settled in selected patients using magnetic resonance or endoscopic-retrograde-pancreatoduodenoscopy (ERCP) (Table 1)[13-16].

The highest relative risk is identified in liver fluke infections (Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis), endemic in South-East Asia[17]. Infection spreads after the ingestion of contaminated fish; and then the flukes colonize biliary tree causing chronic infection and inflammation.

Even if the mechanisms causing the transformation of cholangiocyte into neoplastic cells are nowadays unknown, CCC development in PSC is widely investigated. The risk for patients affected by PSC (as well as other diseases of biliary plate,e.g.Caroli’s disease) to develop CCC in their lifetime is around 3%-30%[15]. Pancreatic enzymes reflux, cholestasis and chronic inflammation leads to cholangiocyte activation, apoptosis, progression of senescence pathways and increased cellular turnover. All these mechanisms are involved in carcinogenesis: Some studies underline a common pathway (interleukin 6, cyclooxygenase-2, nitric oxide,etc.) between inflammation and malignant cellular proliferation acting on hepatic progenitor cells[18-20]. Together with this pathogenetic theory, an alternative carcinogenetic mechanism has been introduced: It is based on mitogenic pathway activation with a consequent multistep tumoral development[21]. These two mechanisms cannot be considered mutually exclusive. Indeed, in PSC patients the presence of cholangiocyte dysplasia was demonstrated together with CCC. The analyses of CCC specimens underlined a wide heterogeneity of gene mutations, however they seem to be polled according to a geographical distribution[22].

CLASSIFICATION AND STAGING

Macrosopic classification

The Bismuth classification, after modified by Corlette, is well known between general surgeons (Figure 1)[23]. It is used to try to define the correct surgical approach and it is based on macroscopic tumor appearance at the pre-surgical imaging. Although this classification is largely used in literature, it has different limits: The absence of longitudinal description of the cancer extension, no relation with prognostic data, and no clearly defined resectability criteria[24,25]. Other classifications have been proposed (e.g., Memorial Sloan-kattering Cancer Centre) but none of them supplanted the use of the Bismuth-Corlette one.

On the other hand, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification is worldwide accepted to define the prognosis[4]. Since the 7thedition of America Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) classification, pCCC has been recognized as a separate disease from the distal CCC. Unfortunately, hystopathological evaluation of surgical specimen, together with pre-operative imaging data is needed to define the correct TMN classification. For these reasons, it cannot be used to define resectability during diagnostic iter.

At the end of 2016, AJCC was revised and the 8thedition of TNM classification was published. Some main changes were introduced in the 8thedition to better depict pCCC prognosis[3,26,27]. T4 stage is no longer linked to Bismuth-Corlette type IV pCCC, as underlined by Ebataet al. T4 pCCC is now defined as a tumor invading the main portal vein or its branches bilaterally, or the common hepatic artery, or unilateral second order biliary radicals with contralateral portal or hepatic artery involvement. According to the current TNM classification, N stage depends on the number of locoregional lymph nodes involved. Furthermore, stage IIIC category was introduced in TNM staging.

Beside these changings, some comments can be pointed out: Liver parenchymal invasion does not define a metastatic disease (T2b) and represent a more favorable prognostic factor than omolateral vascular invasion (T3); the main portal vein invasion (T4) is not a surgical contraindication, but requires vascular reconstruction. A proper N stage can be achieved, according to the 8thedition, only if at least 15 lymph nodes are detected on surgical specimen. A recent paper by Ruzzenteet al[26], tried to evaluate the performance of the new TNM classification in a Western setting. Surprisingly, in this publication, the T4-staged patients had no increased risk of death compared to T1. Furthermore, the ability to predict prognosis of 8thedition N stage was not improved compared to the previous edition. These differences are probably explained by the biological behavior and surgical approach to pCCC in Western and Eastern countries[28,29].

Microsopic morphology

Along with the macroscopic and staging classification, pCCC can be grouped in fourpatterns according to its microscopic morphology[5,20]: (1) Periductal infiltrating: The most common pattern, characterized by an undefined annular thickening of the duct, is frequently associated to perineural and lymphatic invasion; (2) Mixed: Periductal infiltrating associated with a mass forming tumor involving biliary ducts; (3) Intraductal: Mucosal growth associated to segmental bile duct dilatation. biliaryintrapapillary mucinosus neoplasm are included in this pattern; and (4) Papillarymucinosus: This class is characterized by rich mucina secretion that clutter bile ducts. Their diagnosis is frequently associated to liver abscess.

Table 1 Patients that should undergo to screening programs and the techniques that should be applied

Figure 1 Schematic representation of extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts (until second order) showing Bismuth-Corlette classification. CCC: Cholangiocarncioma.

DIAGNOSIS

Literature identifies the characteristics of an ideal diagnostic iter for pCCC: Noninvasive imaging and characterization of pCCC, correct localization of the tumor, presurgical stadiation and resectability evaluation (vascular invasion and biliary spread)[30]. Once CCC is suspected, patients must be referred to specialized surgical centers to complete diagnosis and settle a correct treatment. An incorrect diagnostic pathway exposes patients to delayed diagnosis or repetition of invasive and useless examinations[31].

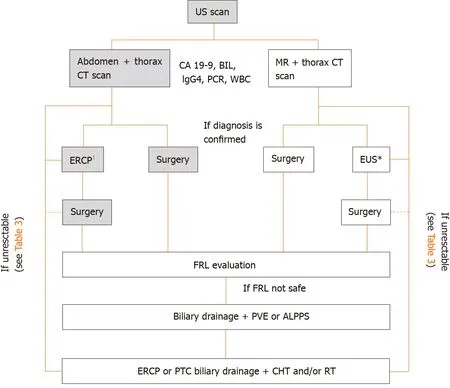

The onset of symptoms is not specific and most of the patients (> 65%-80%) are not resectable at the time of diagnosis[32-34]. pCCC identification can be anticipated by jaundice (90%) or cholangitis (10%). Almost patients subjected to screening are found asymptomatic[5]. A proposed diagnostic flow chart for pCCC is showed in Figure 2.

Non-invasive diagnosis

Ultrasound (US) is considered the first line examination. Even if it is weighted by operator-dependent sensitivity and specificity (55%-95% and 71%-96% respectively) in stenosis visualization, US offers valuable information (also using color-doppler) to establish the future diagnostic plan[35-37].

Computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiographic sequences (MRCP) provide complementary information. CT allows a better definition of local tumor extension, vascular invasion and metastatic disease, but only small details about intraductal extension of pCCC (sensitivity and accuracy of 60% and 92% respectively). However, the introduction of multidetector-row CT (high-resolution) has increased the ability to predict intraductal biliary spread of pCCC[38], in particular when bile ducts are dilated[31].

MRCP has the best sensitivity and accuracy (92% and 76% respectively) in identifying the extension of pCCC, but alone is not enough to establish a correct surgical strategy (e.g., lack in vascular invasion)[39,40]. The importance of a correct MRCP execution is highlighted in Zhanget al[41]review. Indeed, they demonstrated that inadequate MRCP image leads to the re-execution of the exam and up to 60% of MRCP were found incomplete or inadequate if performed in non-specialized centers.

Positron-emissions-tomography has a marginal role in pCCC staging. It can be used to identify metastatic lymph nodes, distant metastases or clarify indeterminate lesions, especially in PSC patients[42,43]. Due to its low sensitivity (< 70%), it can be considered only in selected cases: In fact, distant metastasis are better identified using CT, while EUS is the gold standard in lymphnode staging[37].

Invasive diagnosis

In selected pCCC cases, diagnosis should rely on invasive examinations: ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic colangiography (PTC), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). They should be addressed to clarify the nature of a stenosis (biopsy) or to drain bile ducts[5,32,44,45]. Indded, ERCP and PTC are not more relevant than MRCP images in visualizing biliary tree[46,47]. Parket al[48]showed an accuracy for predicting biliary confluence and intrahepatic bile duct involvement of 91%-87% for MRCP and 85%-87% for CT combined with invasive cholangiography.

Nowadays, PTC is considered a second choice compared to ERCP due to its increased number of complications. However, Zhiminet al[49]described an increased accuracy of PTC (> 90%) in identifying the cranial border of pCCC (especially in pCCC with a proximal localization) compared to ERCP and MRCP.

Endoscopic ultrasound has a controversial role in pCCC diagnosis and management. It provides accurate information about localization of biliary lesions, peribilary tissue involvement, visualization of lymph nodes, hepatic vessels involvement, and it ultimately allows a proper preoperative staging[5,16,32,44,45,50]. However, EUS and EUS fine-needle-aspiration (FNA) sensitivity is reduced from distal to proximal lesions (100% and 83% respectively)[51]. Definition of N staging using EUS needs further studies: Clinical trials are ongoing to identify the role of lymph nodes FNA in predicting pre-operative N stage[52].

Cytological sampling can be obtained through brushing or FNA. It is usefull in nonresectable pCCC or before surgery when diagnosis is not confirmed by non-invaisve techiniques[5,44]. EUS-FNA could also be usefull for cases with negative ERCP-examination[53]. The brushing sensitivity ranges from 20%-40%[54,55]while 79%-83% for FNA[51]. Overall specificity is 92%-100% (the number of cases performed in a hospital highly increase specificity and sensitivity)[16,56]. The low global negative predictive value of cytological sampling using ERCP, PTC and EUS does not exclude the presence of pCCC when a non-neoplastic report is given. It is worth highlighting that, although FNA or brushing allows a proper diagnosis, they are charged by an increased risk of seeding. Only small data are reported on this topic[7,52]. Seeding is a major concern especially during EUS FNA: Indeed, the fine-needle crosses duodenal bulb and peritoneal cavity to sample the pCCC. For these reasons, EUS FNA is contraindicated before liver transplantation[16,52].

Figure 2 Diagnostic and therapeutic work-flow for perihilar cholangiocarncioma.1If cytological confirmation is needed (negative carbohydrate antigen 19-9, positive immunoglobulin G4, and confounding diagnosis at imaging); interrupted line, consider neo-adjuvant therapies. US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MR: Magnetic resonance; CA 19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9; BIL: Bilirubin; IgG4: Immunoglobulin G4; ERCP: Endoscopic-retrogradepancreatoduodenoscopy; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; FRL: Future remnant liver; PVE: Portal vein embolization; ALPPS: Associated liver partition to portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy; PTC: Percutaneous transhepatic colangiography; CHT: Chemotherapy; RT: Radiotherapy.

A further improvement in endoscopic diagnosis is intraductal-EUS. Even if it has almost 91% accuracy[57], it has a lack in tissue sampling and a reduced radial visualization (max 2 cm). Cholangioscopy allows direct visualization of bile duct epithelium and FNA execution and has a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 96%, and 85% and 100%, respectively[58]. Confocal laser endomicroscopy has high sensitivity, specificity and accuracy (89%-71%-82%[59]). However, many concerns are reported concerning standardization and reproducibility of this diagnostic tool, for this reason it is not suggested for a routine use[16].

Serum markers

Carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 is elevated in 85% of pCCC, but it has a variable sensitivity (33%-93%) and specificity (67%-98%) with low positive predictive value (16%-40%). A CA 19-9 cut-off of 129 ng/dL should raise specificity at 70%[2,7,56,60-62]. The main confounding factor is jaundice: A re-evaluation after biliary decompression (BD) is suggested. Another tumor marker is CA-125, but it is seldom used outside clinical trials[7]. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) are specific immunoglobulines produced during IgG4 cholangiopathy, a rare autoimmune disease associated with pancreatitis. The presence of IgG4 suggests IgG4 cholangiopathy, susceptible to steroids’ treatment rather than surgery[63]. New diagnostic approaches are based on liquid biopsy: Detection of cholangiocarcinoma cell-free DNA and circulating tumor cells. Even if some authors reported a usefulness of miRNA measured in bile and blood in pCCC diagnosis, further studies are needed and it probably has a prognostic, more than a diagnostic, role[64-66].

TO DRAIN OR NOT TO DRAIN

BD is a key point during diagnostic and therapeutic management of the pCCC patients. A wide debate is open in literature about this topic and BD must be evaluated according to patient clinical conditions.

Diagnosis and staging in patients with a suspected pCCC are better obtained in absence of foreign bodies in biliary tree. Incorrect indication to BD is one of the most frequent causes of delayed or miss-diagnosis, especially as regards the intraductal extension of the tumor. Hosokawa and colleagues[31]demonstrated that biliary drainage placed before proper diagnosis and staging leads to a higher rate of non-R0 resections. They hypothesized a confounding factor due to artifacts and reduction of the bile duct dilatation.

Sepsis secondary to cholangitis non-responsive to pharmacological treatment is the only absolute indication to BD. Jaundice, itching or cholangitis are not indications to drain the biliary tree during diagnostic time if the patient is a candidate for liver resection. The use of plastic stents or naso-biliary drainages is more suitable than the use of metallic stents. Indeed the fisrt are easily removed to obtain a correct diagnosis[11,5].

Once surgical indication is established, biliary decompression is anyway debated. Wide accordance on drainage is achieved when a two-step procedure (two-setp hepatectomy or portal vein embolization followed by hepatectomy) is needed to increase the future remnant liver (FRL) volume. Indeed, standard surgical procedure in pCCC requires the resection of a large portion of “healthy” liver parenchyma and liver hypertrophy could be needed before surgery. When a two-step procedure is programmed, whilst the risk of bacterial colonization is increased, BD can improve FRL hypertrophy[67]and could reduce morbidity and mortality[68,69]. In this setting, Eastern surgeons are more likely to use a naso-biliary drainage[31], while Western specialists prefer endoscopic stents[29].

Once a one-step hepatectomy is programmed, BD is associated to high risk of septic shock secondary to retrograde cholangitis that could exclude resectable patient from surgery[70]. In a multicenter study, Farges and colleagues[71]reported an increased mortality after BD in patients that underwent left hepatectomy (mainly due to postoperative septic shock) (adjusted OR 4.06, 95%CI 1.01 to 16.3;P= 0.035), while a decreased mortality rate, due to reduction of post-operative liver failure, was observed after right-side hepatectomy (adjusted OR 0.29, 95%CI: 0.11-0.77;P= 0.013). According to their data, the authors suggested that when a right-side hepatectomy is planned in jaundiced patients, BD should be performed and surgery scheduled when bilirubin < 3 mg/dL. Conversely, Celottiet al[72], in their meta-analyses, underlined that patients that underwent pre-operative BD had an increased rate of morbidity and wound infections with no advantages on post-operative mortality. While only a selective use of pre-operative BD is suggested (e.g., patients affected by cholangitis) if one-step hepatectomy is planned, randomized prospective studies are needed to better depict the indications for BD.

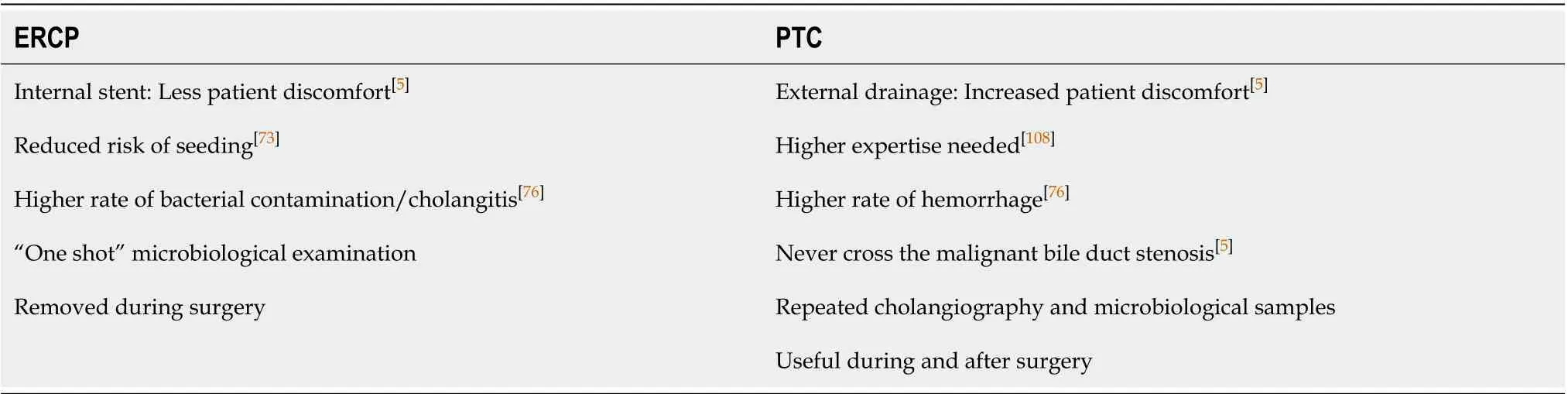

BD can be achieved through percutaneous [Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage (PTBD)] or endoscopic (plastic or metallic stent or naso-gastic tube) approach according to hospital expertise. No definitive data are published on the best technique for BD[67]. Table 2 summarizes pros and cons of the two techniques. A recent paper by Higuchiet al[73]estimated a comparable patient survival and morbidity in patients undergoing PTC or ERCP. While increased post-operative tumor dissemination in PTC group is reported, an increased rate of infection is highlighted in ERCP patients[74,75]. Even if some authors reported the overall superiority of PTC on ERCP[74-76], a recent randomized control[77]trial was prematurely stopped due to the higher rate of presurgical mortality among PTC patients (PTCvsERCP: 41%vs11%). Until PTBD the superiority of a technique will be demonstrated, ERCP with endoscopic stent placement should be considered the first line technique to obtain BD[78]. When curative intent resection is not feasible, ERCP must be pursued in a patient oriented approach.

TREATMENT

Patient and resecability assessment

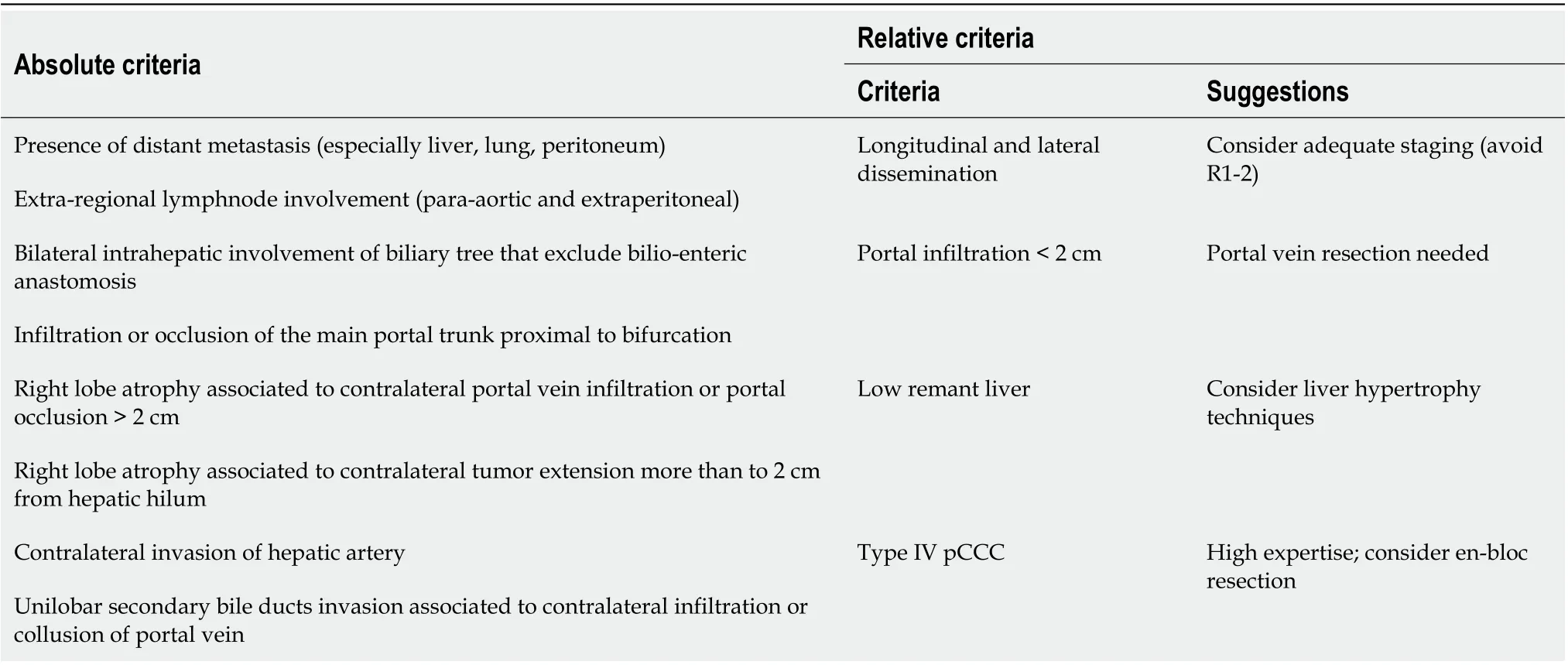

Due to the late onset of symptoms and the aggressive nature of pCCC, less than 50% of the patients are surgically resectable at diagnosis[5]. The main criteria involved in resecability evaluation are highlighted in Table 3.

A recent paper provides a pre-operative risk score designed to predict the risk of intraoperative metastatic disease or locally advanced pCCC (i.e. unresectable) and the post-operative mortality[79]. Through the evaluation of 566 resected pCCC, the authors identified 5 objective criteria (bilirubin > 2 mg/dL; Bismuth classification at imaging; portal vein and hepatic artery involvement at imaging; suspicious lymph node on imaging) that allow the definition of 4 risk categories. An interesting perspective can be the adoption of this score to define the need for up-front neo-adjuvant chemotherapies in high-risk patients.

According to the complexity of surgical approach, resectability decision is strictly connected to a careful evaluation of the patient’s performance status, liver, cardiac,respiratory and kidney function[45]. Nutritional status must be evaluated before surgery and all efforts should be directed towards counterbalancing malnutrition progression. Poor nutritional condition leads to reduced survival, increased post-operative complications and prolonged hospital stay[80-82].

Table 2 Main advantages of two the two techniques available to obtain bile duct drainage

Table 3 Criteria that can be used to identify non-resectable patients

Advanced age was identified as one of the main changings in the characteristics of pCCC population. Despite the advanced age, the rate of resectable patients (70%) was similar in octogenarian and non-octogenarian patients. Post-surgical overall survival was not reduced by age even if a carefully selection of patients is needed. Indeed, 30% of octogenarians (vs6% of under 60 years) were excluded to surgery for poor performance status and poor liver function[83].

Surgical resection

Curative approach to pCCC relies on free surgical margins. Indeed, after R0 resection, 5-year survival reaches 20%-42% in association or not with chemotherapy[8,5,45,67]. The localization of pCCC is one of the most important factors influencing surgical strategy: Isolated bile duct resection is applicable in Bismuth Corlette type I pCCC, while resection of the bile duct confluence is associated to major hepatectomies in the other types. The quantity of liver parenchyma and the number of segments resected depend on the localization of the cranial border of pCCC: Right hepatectomy + S4 in Bismuth-Corlette type IIIa and left hepatectomy in type IIIb. As surgical procedures (especially in type IIIa) require the resection of more than 50% of the liver, post-surgical hepatic failure must be avoided. FRL and liver functional reserve need to be carefully evaluated through liver functional tests (e.g., indocyanine green clearance), imaging techniques and, if possible, liver biopsy. If the predicted FRL is less than the necessary (< 40% in hepatopatic patients, < 30% in normal liver), a single step hepatectomy is related to an increased risk of liver failure and death[84,85]. A two-step procedure (associated liver partition to portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy or simple portal vein ligation) or pre-operative portal vein embolization (PVE) must be settled. PVE is largely adopted in the Eastern Countries (55% of the cases compared to the 7% of Western Countries)[29]. A recent study by Leeet al[86]developed a score to evaluate the risk of “small for size” after resection. They included in their analyses FRL, intraoperative blood loss and prothrombine time > 1.2. Olthofet al[69], in the same year, proposed their own score based on FRL, jaundice at presentation, preoperative cholangitis and immediate post-operative bilirubin > 2.9 mg/dL. While the authors underlined that pre-operative BD increases FRL hypertrophy, post-BD cholangitis reduced the positive effect of biliary decompression on post-operative liver failure rate. Even if PVE is more frequently used in Eastern countries, the rate of post-surgical liver failure is similar to Western ones. A more aggressive approach to liver vascular pedicle, a larger lymphadenectomy and an increased rate of intraoperative transhepatic biliary drainage in the Eastern Countries can counterbalance the effect of PVE hypertrophy[87].

Regardless of the type of hepatectomies, resection of caudate lobe is considered the gold standard. Caudate lobe’s bile ducts open out at bile duct bifurcation and are frequently infiltrated by pCCC. Its removal increases the percentage of R0 resections (59%-87%) with better results in long-term survival (5 years survival from 33% to 44%, resection S1vsnon-resection HR 3.03)[88,89].

Curative surgical strategies cannot leave aside from a histological intraoperative evaluation of bile duct margins (cranial and caudal). Bile duct R0 resection is one of the most important factors influencing long-term follow-up. If neoplastic cells are detected at frozen section, surgical resection will be enlarged till feasible to obtain R0 (60% of the cases[90]). The growth of pCCC is intraluminal and the perineural spread is frequent. A resection of 1 cm above pCCC localization must be considered in the infiltrative type[91], as well as 2 cm in the papillary/mass-forming[92]. A debate in literature is open to understand the results of high-grade dysplasia detection on bile duct margins. While some studies reported comparable patients’- but reduced disease free – survival, other studies showed a reduced 2 and 5-year disease specific survival in N0 R1-high grade-dysplasia patients (2-year, 76.7%vs84.3%; 5-year, 37.5%vs69.3%)[73,93].

Portal vein resection can be headed if focal portal invasion (< 2 cm) of the main trunk is demonstrated. Indeed, portal vein resection does not affect post-resection outcome[4,90,94]. Conversely, hepatic artery resection is related to an increased surgical risk, without a demonstrated positive influence on long-term results[95,96].

In 2012 Neuhauset al[91]proposed a new approach to liver resection in type IIIa pCCC, called “en bloc resection”. In his paper, Neuhaus presented a series of 100 type IIIa pCCC patients that received two different surgical treatements according to the tumor localization: “en bloc resection” in tumors located close to hepatic hilum (n= 50) and standard resection in the others (n= 50). “En bloc resection” consisted in right enlarged hepatectomy + S1, lymphadenectomy and en bloc resection of biliary confluence, extrahepatic bile duct, portal vein bifurcation and right hepatic artery (portal vein reconstruction is needed). 3 and 5-year survival was superior in “en bloc” group (35% and 25%vs65% and 58% respectively) without an increase in surgical complications. Other authors adopted this approach with reported comparable results[97]. The “en bloc resection” is not feasible in left hepatectomy because the no touch approach on hilum is impossible, unless resection and reconstruction of the right hepatic artery are being considered.

In 2017, Kawabataet al[98]proposed their own surgical technique based on reduced liver manipulation and tumor spread. They described an ab-initio parenchymal transection prior to liver mobilization. Two-year survival was increased in the study group (95%vs58%) with a decrease in surgical complications.

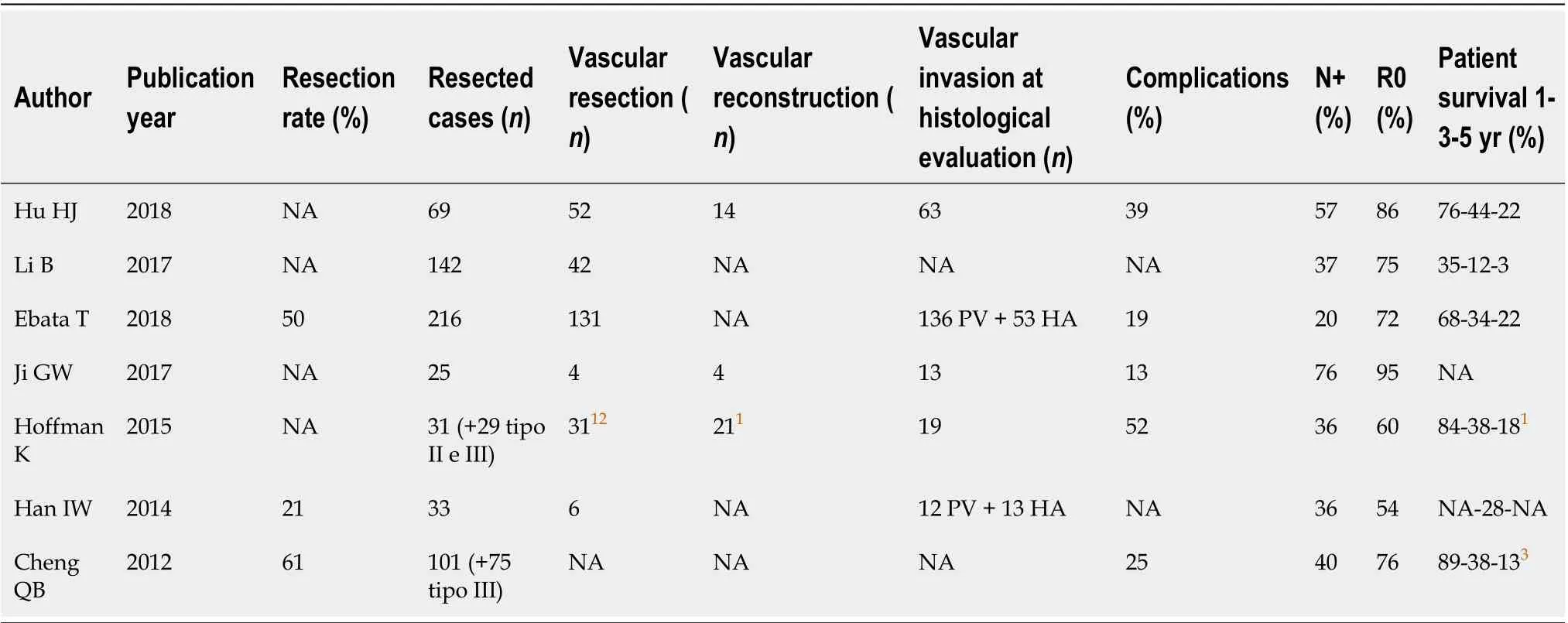

Bismuth-Corlette Type IV pCCC deserves a peculiar consideration (Table 4). It was considered a surgical contraindication for several years due to the bilateral bile duct invasion. However, in the last few years, the surgical approach to this type of pCCC changed due to the Japanese group’s contributions. In 2018, they published[99]a series of 216 patients with Bismuth Corlette type IV pCCC that underwent surgical resection: R0 resection was achieved in 76.2% of the cases, post-surgical morbidity was 41.6% and the 5-year survival was superior in the resected patients (32.8%vs1.5%). Even if the resection of type IV pCCC is feasible and the results are promising, two main concerns are emerging: An undiagnosed vascular invasion often detected at histopathological evaluation and the high rate of N positive specimens[100,101]. The adoption of an en-bloc approach can be suggested in this type of pCCC to avoidunexpected vascular invasion diagnosis. Furthermore, neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be useful in type IV pCCC to select chemo-responsive tumors, reduce the possible futile resections and improve the extent of R0 rate.

Table 4 Articles reporting resection of type IV perihilar cholangiocarncioma according di bismuth

Liver transplantation

In unresectable pCCC, liver transplantation (LT) can be considered within research protocols and with strict inclusion criteria[102]. These criteria are: Tumor smaller than 3 cm, no evidence of lymph node involvement or metastatic disease, and no prior percutaneous or endoscopic biopsy[103]. The initial results of LT for pCCC were poor. Indeed, overall survival (OS) following LT alone for incidentally diagnosed pCCC in PSC are < 40% at 3-year[104]. LT for pCCC gained new enthusiasm with the publication of Mayo Clinic results: In their studies they identified the risks for disease progression and recurrence, and a multimodal therapy (neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy is mandatory prior to listing) was successfully applied. In the published series of LT performed at Mayo Clinic, the LT group with neoadjuvant chemoradiation (38 patients) achieved better 1 year (92%vs82%), 3 years (82%vs48%), and 5 years (82%vs21%) overall survival (OS) when compared with the resection group (26 patients). Consistently, the LT group experienced lower post-transplant recurrence (13%vs27%)[105]. Ethunet al[106]compared 191 patients that underwent curative resection with 41 patients that received LT (with Mayo Clinic Protocol) for pCCC. In LT group, 38% of the patients were excluded. Patients who underwent transplant for pCCC showed improved OS compared with resection (5-year: 64%vs18%;P< 0.001). The same results were obtained if patients with tumors < 3 cm with lymph-node negative disease and without PSC patients from resection group (5-year: 54%vs29%;P= 0.03).Resective surgery in pCCC is the standard of care for suitable patients outside the setting of PSC[107]. To date, even if there are no randomized controlled trials, LT after aggressive neoadjuvant therapy (including external beam and transluminal radiation, as well as systemic chemotherapy) seems like an adequate treatment for both unresectable pCCC, as well as pCCC arising in the setting of PSC[108].

Laparoscopic exploration

The role of laparoscopic exploration (LE) decreased over time together with the increase of sensibility and specificity of imaging techniques. Routine LE is not recommended, but it can be useful in T2/T3 pCCC according to AJCC classification or type III and IV according to Bismuth-Corlette[92,109]. LE is the only way to detect peritoneal metastasis prior to laparotomy, due to the low predictive value of noninvasive technique. Furthermore, routine opening of the lesser sac during LE can help in detecting metastatic lymphnode of hepatic artery (N2 stage)[110]. A recent meta-analysis[111]collected 8 studies evaluating the role of LE: 32.4% of the patients were found unresectable at exploration with a sensitivity of 56% and a specificity of 100%. In another study, sensitivity of LE increased from 24% to 41% using intraoperative ultrasound[112].

Lymphadenectomy

Lymphadenectomy is an essential part of the surgical intervention, as well as bile duct and liver resection. In pCCC, hilar, hepatic artery, portal vein, bile duct, celiac trunk and retroduodenal lymph nodes must be resected. The role of lymphadenectomy is to obtain an adequate post-surgical staging, even if some authors reported a survival benefit[88,113,114]. The 8thedition of TNM classification identifies 15 lymph nodes as the minimum number to obtain an adequate N staging (N1 when 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes are positive, N2 when more than 4 regional lymph nodes are positive)[4]. Regional lymph nodes are located in the hepatic hilum and in the hepatoduodenal ligament (pericholedochal nodes). The first systematic review on lymphadenectomy was published in 2015[115]. Beside AJCC classification, Kambakambaet al[115]rose criticism about the minimum number of dissected nodes. Indeed, in their review, only 9% of the series reported a number of dissected lymph nodes > 15, while N positivity ranged from 31% to 58%[116,117]. Their analyses showed that 7 is the number of lymph nodes that ensures the highest detection rate of N1 and the lowest rate of potentially understated N0 patients. The impact on survival of extended lymphadenectomy (> 15 lymph nodes) is debated, because it does not improve 5-year survival and median OS with an increased rate of surgical complications[5]. The presence of malignant cells within dissected lymph nodes (N1) has a detrimental impact on patient survival: 3-year survival 35%vs10% in N0vsN1 patients[115]. It was recently suggested that the presence of a small number of metastatic lymph nodes (lymph nodal ratio < 0.2 or number of lymph node < 4) does not exclude good long-term survival[114,118].

Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and palliative treatments

The role of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in pCCC is not clearly identified and it is mostly adopted in clinical studies.

The Mayo Clinic protocol combined neoadjuvant chemosensitization with 5-fluorouracil, external beam radiotherapy plus brachytherapy boost and orthotopic liver transplantation for patients with stage I and II pCCC. In a retrospective series, thirty-eight patients underwent liver transplantation while 54 patients were explored for resection. Patients receiving transplantation had better one-, three- and five-year survival (92%, 82% and 82%) compared to resection (82%, 48% and 21%,P= 0.022). Transplanted patients had fewer recurrences compared to resection (13%vs27%)[105]. The ongoing phase III TRANSPHIL trial is comparing resection with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy capecitabine-based and orthotopic liver transplantation[102].

Resected patients, except the R0 pT1N0M0 ones, as well as non-resected patients must undertake chemotherapy with adjuvant intent. The role of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is not well defined due to the lack of data from randomized trial[8]. On the contrary, the phase III randomized BILCAP trial, comparing adjuvant capecitabine with observation in resected biliary tract cancers, showed an increased OS for the experimental arm in the protocol-specified sensitivity analysis (adjusting for minimisation factors, nodal status, grade and gender). Specifically, median OS in the capecitabine arm was 53 movs36 mo in the observation group (P= 0.028)[119]. Diversely, the phase III Prodige 12-Accord 18 trial, comparing chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and gemcitabinevsobservation after resection, failed to show an increase in OS (P= 0.74)[120].

A further phase III study, comparing cisplatin and gemcitabine treatmentvsobservation (ACTICCA-1) is open and recruiting patients[121].

A meta-analysis evaluating studies of adjuvant chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy in biliary tract cancers found a nonsignificant improvement in OS compared with adjuvant treatment compared with surgery alone (P= 0.06). However, patients treated with chemoradiotherapy (OR 0.61) or chemotherapy (OR 0.39) had greater benefit with compared to radiotherapy alone (OR 0.98,P= 0.02) and, specifically, the greatest benefit was in those patients with nodes positive (OR 0.49,P= 0.004) and R1 disease (OR 0.36,P= 0.002)[122]. Another meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies confirmed the improvement in OS given by adjuvant chemotherapy, with a 41% of risk of death reduction compared with observation after resection (HR 0.59,P< 0.0001)[123]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials showed no effect of adjuvant treatment on OS improvement (HR 0.91) and a mild improvement in recurrence-free survival (HR 0.83). Neither the lymph-node positive (HR 0.84) nor the surgical margin positive subgroups (HR 0.95) had an OS prolongation with adjuvant treatment[124]. Nassouret al[125]retrospectively analyzed the National Cancer Database to evaluate the role of adjuvant chemotherapy (AT) on pCCC. They found the patients that received AT were younger, with a higher pathological T and N staging, a higher rate of non-R0 resections and a longer hospital stay than patients that did not undergo AT. After a propensity match analyses, they found that AT had a beneficial role on 5-year survival in all resected patients, especially in high risk (non-R0 resection) ones. Furthermore, an advantage on 5-year survival was showed for patient that underwent chemo-radiotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone.

In case of locally-advanced unresectable disease, the role of radiation therapy remains unclear[8]. A phase II trial compared gemcitabine plus oxaliplatinvschemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin. The trial closed before completion due to slow recruitment, showing an increased median OS (19.9 movs13.5 mo, HR 0.69) and progression free survival (11.0 movs5.8 mo, HR 0.65) for the chemotherapy arm[126]. A small series using image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy both in gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts cancers demonstrated the feasibility of the procedure, allowing safe dose escalation[127].

Exclusive chemotherapy remains a suitable option in case of unresectable disease. The phase III UK ABC-02 study has established the cisplatin/gemcitabine chemotherapy as the new standard of care in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Median survival was 11.7 for the combination therapy compared with 8.1 mo for the gemcitabine only comparator arm (P< 0.001)[128]. The benefit of the combination was present independent of age (inferiorvssuperior to 65 years), gender, primary tumour site (intravsextrahepaticvsgallbladdervsampullary), stage of disease (locally advancedvsmetastatic) and previous therapy (surgeryvsstenting)[129]. In case of altered renal function, oxaliplatin may be used instead of cisplatin, while in case of poorer clinical conditions, gemcitabine monotherapy may be a choice[8].

Beyond failure of first line treatment, evidence is scarce. A recent systematic review of the literature gathering 25 non-randomized prospective and retrospective studies reported a median progression-free survival (mPFS) and median overall-survival (mOS) of 3.2 and 7.2 mo, respectively[130]. A large multicenter Italian survey and pooled analysis with published data found a mPFS of 3.1 and median OS of 6.3 mo[131]. Recently, the results of a phase III trial (ABC-06) comparing modified FOLFOX to best supportive care found an advantage in mOS (6.2 movs5.3 mo) with adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.69. Patients treated with FOLFOX had a prolongation of median radiological PFS or 4 mo. Moreover, the study showed a 1% rate of complete responses, 4% of partial responses and a 28% of cases had disease stabilization. The overall disease control rate was 33%. Due to the results of this trial, modified FOLFOX should be considered the standard of care in the second-line treatment of BTCs[132].

Isocitrate dehydrogenase isoenzyme 1 (IDH1) mutations are present in 15% of patients with CCC. Recently, the results of treatment with ivosedinib, an oral smallmolecule inhibitor of mutant IDH1 (mIDH1), have been presented. In patients with mIDH1 progressed to first line treatment, mPFS was 2.7 mo with ivosedinibvs1.4 mo for placebo (HR 0.37,P< 0.001). MOS was 10.8 mo for ivosedinibvs9.7 mo for placebo (10.8 movs9.7 mo for placebo, HR 0.69,P= 0.06). However, mOS for placebo decreased to 6 mo after considering a 57% crossover-rate from placebo to experimental treatment and the difference in mOS between ivosedinib and placebo became statistically significant (HR 0.46,P= 0.0008)[133]. Ivosedinib is the first targeted molecular agent showing efficacy in the treatment of advanced CCC and its use will probably become a standard in the second-line treatment of mIDH1 CCC.

In patients with an estimated survival longer than 3 mo, bile duct decompression should be reached. Percutaneous or endoscopic approaches are both possibile. ERCP has the advantage of a totally internal stent, without the discomfort of PTBD (less pain and aesthetic impact). On the other hand, endoscopic stents are not easy to arrange in type III and IV pCCC. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary stent placement is an effective alternative to endoscopic stent to relieve cholestasis77. Combined seed intracavitary irradiation with125I can be applied to obtain a better stent patency and survival[134,135].

OUTCOME AND RESULTS

Survival after pCCC diagnosis is poor and frequently accompanied by a prolonged hospitalization and a wide use of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques. Median survival is 12 mo in patients not susceptible to surgery and 38 (range 25-40) mo in radically resected patients. Koerkamp and colleagues in 2015[136]evaluated a population of 306 patients that underwent surgical resection for pCCC: Overall 5-year survival was 35%, while it increased to 50% in the 122 (42%) patients N0R0 resection. Excluding R2 patients and patients with intra-hospital death, the median time to recurrence was 31 mo with a 3-year survival after recurrence of 18%. Eastern postoperative survival is slightly better that Western one (median OS of 56 movs43 mo respectively,P= 0.028), depicting a possible more aggressive behavior of pCCC in Western world[29].

In literature, many variables influence 3 and 5-year survival: Resection margins, type of resection, T stage, N stage, staging, lymphovascular invasion and caudate lobe invasion[88,137,138]. T stage and N positivity are burdened by the highest Hazard Ratios: N1 HR 2.32 (5-year survival N1vsN0 11%vs35%) and T3-4 HR 1.86 (5-year survival T1-2vsT3-4 47%vs19%)[137]. R0 resection was recently underlined as the main factor influencing the outcome, irrespective of the tumor staging[31,139]. Three and five-year recurrence-free survival was 57% and 49% in R0 resection, while 31% and 16% in R1 resection. In stage I, II and III, R0 resection was directly related to segment 1 resection and age > 56 year[31]. Lymphovascular invasion was identified as one of the detrimental prognostic factors on patient and disease free survival. Its role was investigated in lymph nodes positive and negative patients and in both was identified as a detrimental factor[138]. Furthermore, lymphovascular invasion resulted in an increased percentage of patients with lymph nodes metastasis, but not with a decrease in R0 rate, also in Bismuth-Corlette tipe IV pCCC[101,137,140].

In 2017, van Vugtet al[95]evaluated the impact of vascular invasion on 674 patients affected by pCCC. Median OS was considered independently from curative resection. They found that any hepatic artery involvement is related to poor prognosis (median OS: 16.9 (13.2-20.5) movs10.3 (8.9-11.7) mo,P< 0.001), while unilateral or main portal vein involvement was not related to reduced median OS [14.7 (11.7-17.6) movs13.3 (11.0-15.7) mo,P= 0.116]. This paper confirmed the results provided by other authors and highlighted the necessity of a further modification of the 8thAJCC classification. Indeed, the T4 classification does not discriminate arterial or main portal vein infiltration with a reduced ability to predict patient outcome[26].

The resection benefits have to deal with the high surgical morbidity and mortality of pCCC. In both Western and Eastern Centre, 90-d surgical mortality ranges around 10%.

The 5-year survival rate for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in patients receiving a liver transplant is greater than 70%[105], although these data are affected by selection bias. A number of factors were identified as predictors of outcomes in pCCC liver transplantation: Elevated CA 19-9, portal vein encasement, perineural invasion and absence of vital tumor at explant histopathological examination[140-142]. Recent evidence showed that overall survival is affected by the amount of necrotic tumor after neoadjuvant therapy (patients with minimal response were 9.0 times more likely to die than patients with a complete tumor necrosis) and by lymphovascular invasion[140].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is characterized by high mortality and low rate of resectable patients. The main issue for surgeons is to obtain the most rapid and accurate diagnosis. For this reason, patients must be referred to specialized centers after a suspect diagnosis. Biliary drainage is an important tool in non-resectable patients and in those that are candidate to two-stage hepatectomy. It must be obtained after a definitive diagnosis. Even if surgery represents the only curative option, it is still charged by reduced long-term survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to thank “Associazione Italiana Copev per la prevenzione e cura dell'epatite virale Beatrice Vitiello- ONLUS” for the valuable support and Erica Bosco for langue review.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年25期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年25期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- TBL1XR1 induces cell proliferation and inhibit cell apoptosis by the PI3K/AKT pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Development of innovative tools for investigation of nutrient-gut interaction

- Management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Middle East

- Quality of life in patients with gastroenteropancreatic tumours: A systematic literature review

- Functionality is not an independent prognostic factor for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

- Risk factors associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter case-control study in Brazil