Survival in men older than 75 years with low- and intermediate-grade prostate cancer managed with watchful waiting with active surveillance

Tzuyung D. Kou, Siran M. Koroukian, Pingfu Fu, Derek Raghavan, Gregory S. Cooper, Li Li,4

1. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA

2. Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine,Cleveland, OH, USA

3. Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas Healthcare System, Charlotte, NC, USA

4. Department of Family Medicine-Research Division, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland,OH, USA

Survival in men older than 75 years with low- and intermediate-grade prostate cancer managed with watchful waiting with active surveillance

Tzuyung D. Kou1,2, Siran M. Koroukian1,2, Pingfu Fu1,2, Derek Raghavan2,3, Gregory S. Cooper1,4, Li Li1,2,4

1. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA

2. Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine,Cleveland, OH, USA

3. Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas Healthcare System, Charlotte, NC, USA

4. Department of Family Medicine-Research Division, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland,OH, USA

Objective:Recent studies have reported the underuse of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk prostate cancer in the United States. This study examined prostate cancer–specific and all-cause death in elderly patients older than 75 years with low-risk tumors managed with active treatment versus watchful waiting with active surveillance (WWAS).

Methods:We performed survival analysis in a cohort of 18,599 men with low-risk tumors(early and localized tumors) who were 75 years or older at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis in the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database (from 1992 to 1998) and who were followed up through December 2003. WWAS was defined as having annual screening for prostate-specific antigen and/or digital rectal examination during the follow-up period. The risks of prostate cancer–specific and all-cause death were compared by Cox regression models. The propensity score matching technique was used to address potential selection bias.

Results:In patients with well-differentiated (Gleason score 2–4) and localized disease, those managed with WWAS without delayed treatment had higher risk of all-cause death (hazard ratio 1.20, 95% confidence interval 1.13–1.28) but a substantially lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (hazard ratio 0.62, confidence interval 0.51–0.75) than patients undergoing active treatment.Patients managed with WWAS with delayed treatment had comparable mortality outcomes. Sensitivity analyses based on propensity score matching yielded similar results.

Conclusion:In men older than 75 years with well-differentiated and localized prostate cancer,WWAS without delayed treatment had a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death and comparable all-cause death as compared with active treatment. Those patients in whom treatment was delayed had comparable mortality outcomes. Our results support WWAS as an initial management option for older men with well-differentiated and localized prostate cancer.

Epidemiology; watchful waiting; prostate cancer

Introduction

Widespread use of the prostate-specific antigen(PSA) test for screening has led to a substantial shift in the prostate cancer stage at diagnosis [1, 2], with more patients now receiving a diagnosis of early-stage localized disease[3, 4]. PSA testing for prostate cancer screening and diagnosis appears to decrease with advancing age. Most patients in the United States continue to receive active treatment,such as radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. Alternative management such as watchful waiting in patients with early and localized tumors remains underused [5, 6]. The benefit of prostate cancer screening particularly among older men has been questioned, and PSA-based screening is no longer recommended [7]. A small but significant proportion of men who are 75 years or older continue to undergo PSA testing [5]. The appropriate treatment option for those elderly patients continues to be an active area of research.

Cohort studies have shown that patients with early and localized prostate cancer have a lower risk of cancer-specific death if they are not treated compared to those who receive treatment. Randomized studies have shown that radical prostatectomy might have lower risk of short-term mortality outcomes but without significant long-term survival benefit [8–18]. In those studies, very few elderly patients older than 75 years were included, and subgroup analyses on these elderly patients were most likely underpowered. The definition of watchful waiting differs between studies. It can be defined as encompassing patients who do not undergo any aggressive treatment regardless of any surveillance procedures after diagnosis. Patients who do not undergo aggressive treatment but who are monitored could be very different from patients who do not undergo aggressive treatment and are not monitored. Using the same linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare administrative claims database, we specifically compared the prostate cancer–specific and all-cause mortality outcomes between patients managed with watchful waiting with active surveillance (WWAS) and those who underwent active treatment in men 75 years or older with well-differentiated to moderately differentiated and localized prostate cancer.

Methods

Study population and data sources

The study population comprised men 75 years or older in whom well-differentiated to moderately differentiated and localized prostate cancer was diagnosed between 1992 and 1998, and with 5–12 years of follow-up. In the linked SEER-Medicare data files, the Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File(PEDSF) contained cancer-related information from within 4 months after the initial diagnosis; the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) files contained inpatient claims records; the outpatient files contained claims records from outpatient providers; the National Claims History (NCH)files contained claims records from physicians. The Cancer Institutional Review Board at Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (Cleveland, OH, USA) approved this study.

Patients who received a diagnosis before the age of 75 years,without Medicare Part B coverage, or enrolled in ahealth maintenance organizationfrom at least 1 year before diagnosis to the end of the study period, or who received Medicare benefit because of end-stage renal disease were excluded from the study cohort.

From 1992 to 1998, prostate cancer was diagnosed in 157,078 patients. Of these, 60,124 patients were excluded because they did not have Medicare Part B coverage or were enrolled in managed care programs from at least 1 year before diagnosis to the end of the study period; 60,530 patients received a diagnosis of prostate cancer when they were younger than 75 years; 3642 patients did not survive the first 6 months after diagnosis; 8102 patients had distant or unstaged tumors and or with a Gleason score of more than 7 or an unknown Gleason score, leaving 18,599 patients aged 75 years or older for the present study.

Study measures

Survival outcomes

The duration of survival was determined from the SEER date of diagnosis to the Medicare date of death. Those patients who were alive at the end of follow-up were censored. Prostate cancer–specific death was defined as prostate cancer as the cause of death (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ninth edition (ICD-9) code 185, or International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O)code C619). In the analysis of prostate cancer–specific death,patients without prostate cancer–specific death information or alive at the end of follow-up were censored. Since the study focused only on patients with well-differentiated to moderately differentiated and localized tumors, we excluded from the current analysis patients who did not survive the first 6 months after diagnosis, as they were likely acutely ill from all causes.

Independent variables

Treatment modalities

Treatment modalities were captured in both the SEER summary file and the linked Medicare claims records. The complete list of ICD-9, Current Procedural Terminology, fourth edition(CPT-4), and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System(HCPCS) codes used to describe treatment received are available on request. We categorized the treatment modalities into(1) active treatment, (2) WWAS without delayed treatment, (3)WWAS with delayed treatment, (4) hormonal therapy only, and(5) no treatment. Active treatment was defined as having radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy,or a combination of treatments within two different study time frames: (1) the first 2 years after prostate cancer diagnosis; and(2) all available follow-up. WWAS was defined as having at least one annual PSA test or digital rectal examination (DRE)during the follow-up period in the absence of aggressive treatment. Patients who initially received WWAS but received active treatment within the study time frames after diagnosis were considered as receiving WWAS with delayed treatment.

Using the Medicare inpatient and outpatient files, we extracted information on the use of any prostate cancer surveillance procedure from the SEER date of cancer diagnosis to the two different study time frames defined above. The PSA test was captured by HCPCS code G0103 and CPT-4 code 84153,and DRE was captured by HCPCS code G0102 and CPT-4 code 99211.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The demographics included race, SEER registry location, and marital status at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis. Race was categorized as Caucasian, African American, Asian, Hispanic,and other or unknown. Age at the time of initial prostate cancer diagnosis was categorized into three groups: 75–79 years,80–84 years, and older than 85 years. The year of initial prostate cancer diagnosis, urban or rural location, presence of other cancer diagnosis, marital status, location of residence, and SEER registry location at the time of diagnosis were also documented.The linked SEER-Medicare data do not include patient-level socioeconomic information; therefore, we used the ZIP code–level education and median household income information as proxy measures of individual socioeconomic status.

Tumor stage and grade

We used the SEER historical stage in the analysis. Tumor grade is known to be associated with survival outcomes. Thus,we considered a well-differentiated pattern (Gleason score 2–4) in localized tumors as low-risk disease, and a moderately differentiated pattern (Gleason score 5–7) in localized tumors as moderate-risk disease. Ungrouping the tumor grade information into an individual Gleason score category to create more refined categories was not possible with the SEER data.

Comorbid conditions

Because comorbid conditions are important factors influencing treatment decisions and outcomes [19, 20], we also included comorbidity scores derived from claims data for services received 1 year before cancer diagnosis, using the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index [21]. The Medicare inpatient and outpatient files were evaluated for the presence of relevant diagnosis codes in the 12 months preceding cancer diagnosis. The Charlson comorbidity index was originally designed as a measure of the risk of death attributed to comorbid conditions. The Charlson score considers up to 22 comorbid conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, and each condition is assigned a score depending on the disease-specific risk of death. In this study, the Charlson comorbidity index was categorized as 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more.

Statistical analysis

We conducted survival analyses on two subsets of patients:those with low-risk disease (Gleason score 2–4, localized or regional tumor) and those with moderate-risk disease (Gleason score 5–7, localized or regional tumor). The chi-square statistic was used to compare the differences in demographic and clinical attributes. The Studentttest was used to compare the mean age of the study groups. A log-rank test was used to compare the overall survival. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess association between different treatment modalities defined with two different time frames and the mortality outcomes (prostate cancer–specific death and all-cause death), with adjustment for available variables in the linked SEER-Medicare database. The proportional hazards assumption was met.

To further address the issue of selection bias related to patients managed with WWAS without delayed treatment, we used the propensity score matching method [22]. In the propensity score model, patients receiving WWAS without delayed treatment were considered as the cases and those receiving active treatment were considered as the controls. Patients receiving WWAS with delayed treatment were excluded in this sensitivity analysis. A 1:3 matching ratio was used to maximize the number of cases and controls in the analysis.Propensity score with 1:3 case-to-control ratio matching from the study cohort generated a subset of 1123 cases and 3468 controls. The propensity score was calculated on the basis of the available patient clinical and demographic variables in Table 1. We evaluated the performance of the propensity score model using both theC-statistic value and box plots of probability values before and after matching. We then used a univariate Cox proportional hazards model to compare the mortality outcomes between patients managed with WWAS and those managed with active treatment in the overall propensity score–matched cohort. Additional analyses compared the mortality outcomes in two subsets of the matched cohort:(1) patients with well-differentiated and localized tumors (low risk) and (2) patients with moderately differentiated and localized tumors (moderate risk). Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Intercooled Stata 9 (StataCorp,College Station, TX, USA).

Results

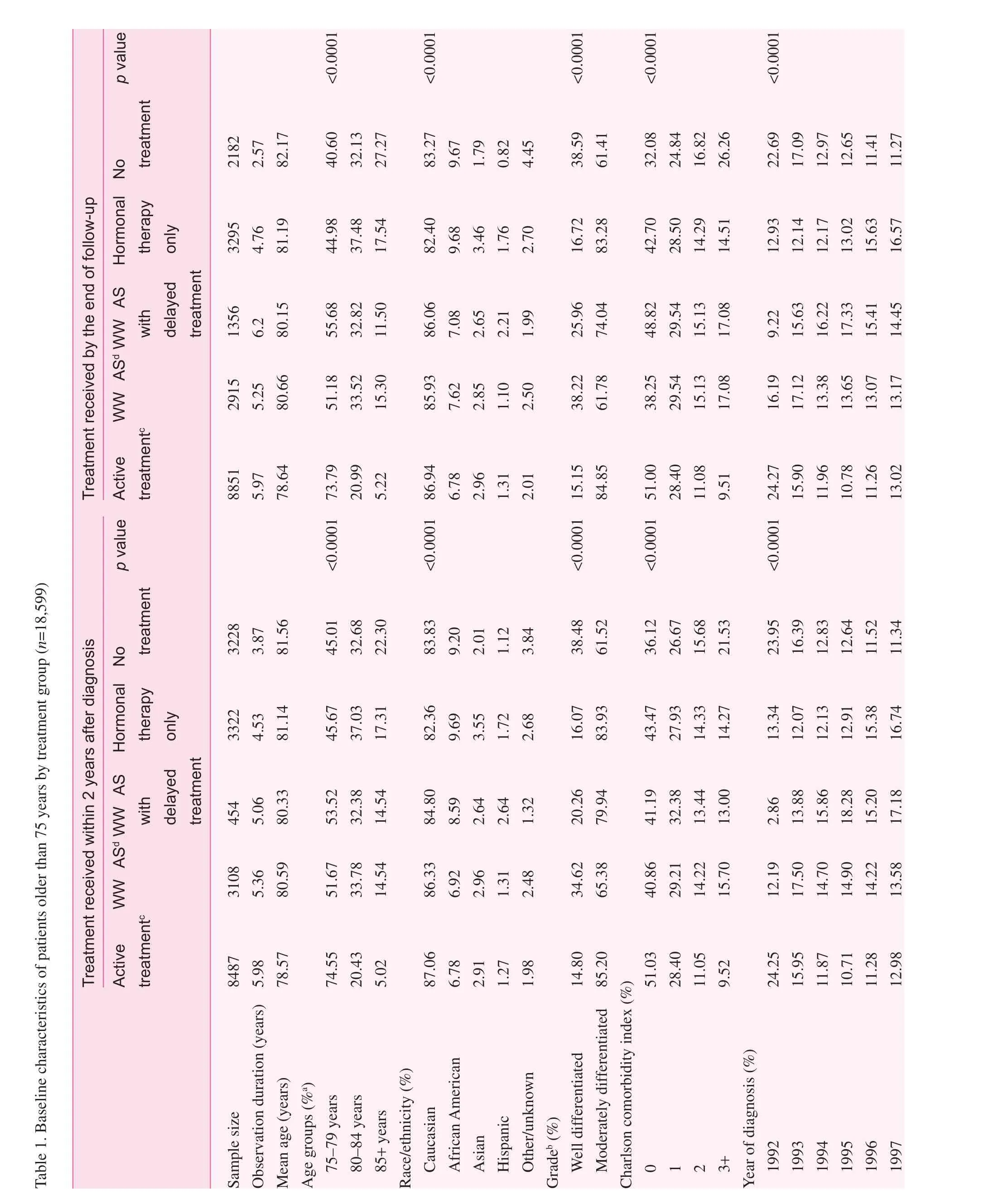

Patient baseline characteristics

The analytical cohort comprised 18,599 prostate cancer patients aged 75 years or older at diagnosis. During the first 2 years after diagnosis, 3108 patients were managed with WWAS without delayed treatment, 454 were initially managed with WWAS but had delayed treatment within the first 2 years after diagnosis, 3322 received only hormonal therapy,3228 received no treatment, and 8487 received active treatment (Table 1). There was a small but significant difference in the distributions of race and ethnic categories across the three groups (p<0.0001). Patients in the active treatment group were likelier to live in areas with higher median household income and with a higher percentage of the population with a college education, and were less likely to have other comorbid conditions compared with those receiving WWAS without delayed treatment and WWAS with delayed treatment. By the end of the follow-up period, some WWAS patients received additional treatment more than 2 years after diagnosis (Table 1).

Within the first 2 years after diagnosis, patients managed with WWAS without delayed treatment and patients managed with WWAS with delayed treatment were likelier to have well-differentiated tumors (Gleason score 2–4) compared with patients in the active treatment group (34.62%, 20.26%,and 14.80%, respectively,p<0.0001). A similar trend was also observed when we compared treatment received by the end of the follow-up period.

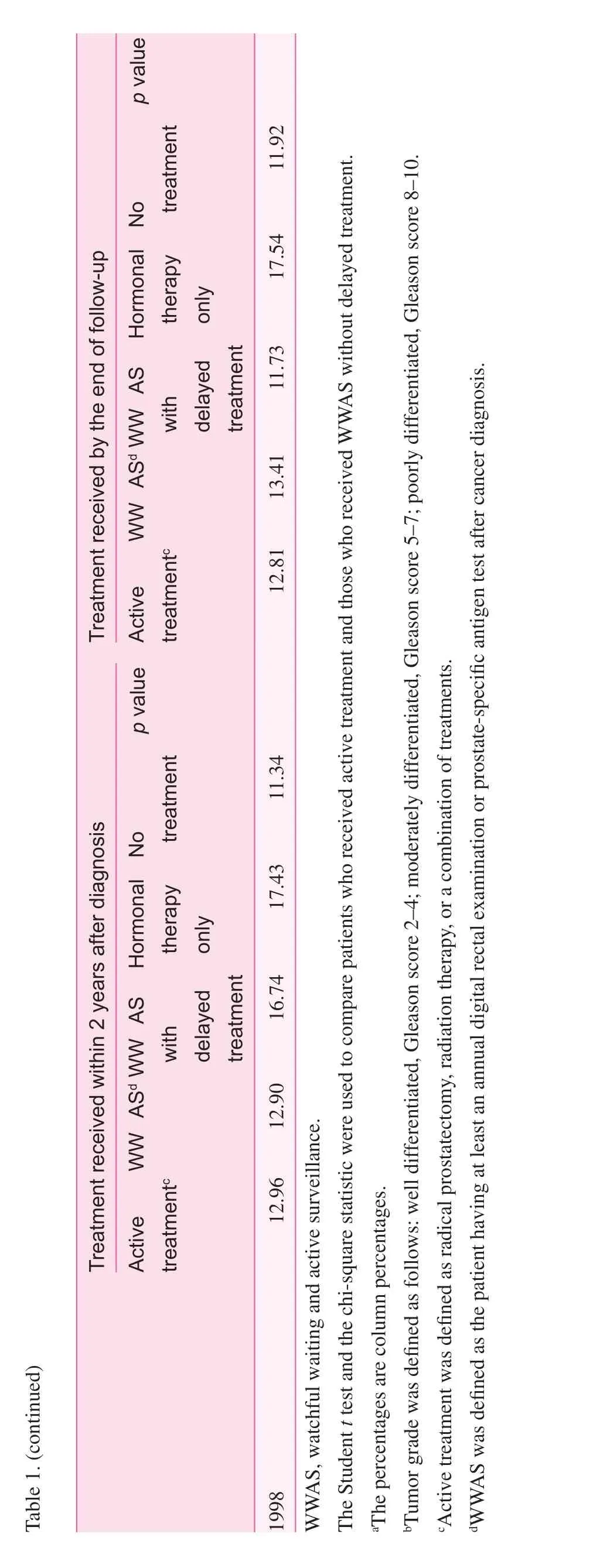

Survival analysis in the full analytical cohort

With up to 11 years of follow-up, 54.68% of patients were deceased at the end of the study period. Of these deaths, 6.51%were attributed to prostate cancer. In the analysis of the entire cohort, there were significant differences in survival experience (log-rank test,p<0.0001, Fig. 1). Patients in the active treatment group had a lower risk of all-cause death compared with patients managed with WWAS and those managed with WWAS with delayed treatment.

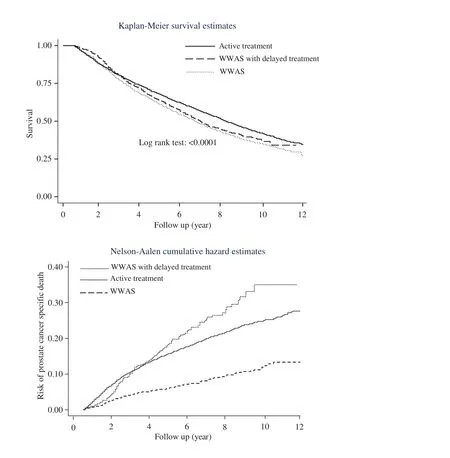

In the full study cohort regardless of the Gleason score,patients managed with WWAS without delayed treatment within 2 years after diagnosis had a significantly higher risk of all-cause death (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.13–1.28) and a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.51–0.75) compared with patients in the active treatment group(Table 2). Patients who were initially managed with WWAS but then received delayed treatment had a higher risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.31–2.34) and a higher risk of all-cause death (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.34).The same trend was also observed in the analysis comparing risk of death outcomes between treatment modalities received by the end of follow-up.

Survival in patients with low-risk tumors

Fig. 1. Significant difference in the survival experience and the risk of prostate cancer–specific death between the active treatment group, the group managed by watchful waiting with active surveillance (WWAS) with delayed treatment, and the group managed by WWAS without delayed treatment in elderly patients older than 75 years. Active treatment was defined as radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or a combination of treatments. WWAS was defined as the patients having at least an annual digital rectal examination or prostate-specific antigen test after cancer diagnosis.

In the first set of analyses, mortality outcomes were compared between treatment modalities received within 2 years after diagnosis. In patients with well-differentiated (Gleason score 2–4) and localized tumors, those managed with WWAS without delayed treatment had a significantly elevated risk of allcause death (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31) but a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.84)compared with patients in the active treatment group. Patients who were initially managed with WWAS but who received delayed treatment had an elevated but not significant risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.57–3.28)and all-cause death (HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.82–1.47). Patients who received hormonal therapy only had a higher risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.35–2.50) and allcause death (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.05–1.39).

Among patients with moderately differentiated (Gleason score 5–7) and localized tumors, those managed with WWAS without delayed treatment had a statistically significantly higher risk of all-cause death (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.14–1.32)and a lower risk of prostate cancer – specific death (HR 0.73,95% CI 0.58–0.90) than those in the active treatment group.Patients who were initially managed with WWAS but who received delayed treatment had a significantly higher risk ofprostate cancer–specific death (HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.33–2.50)and all-cause death (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.01–1.38).

Table 2. Multivariate cox regression models

In the analysis comparing risk of death outcomes between treatment modalities received by the end of the follow-up period, similar trends in the risk of prostate cancer–specific death and all-cause death were observed in patients with WWAS without delayed treatment compared with active treatment (Table 2). Patients initially managed with WWAS but who received delayed treatment had a risk of all-cause death comparable to that of patients in the active treatment group.

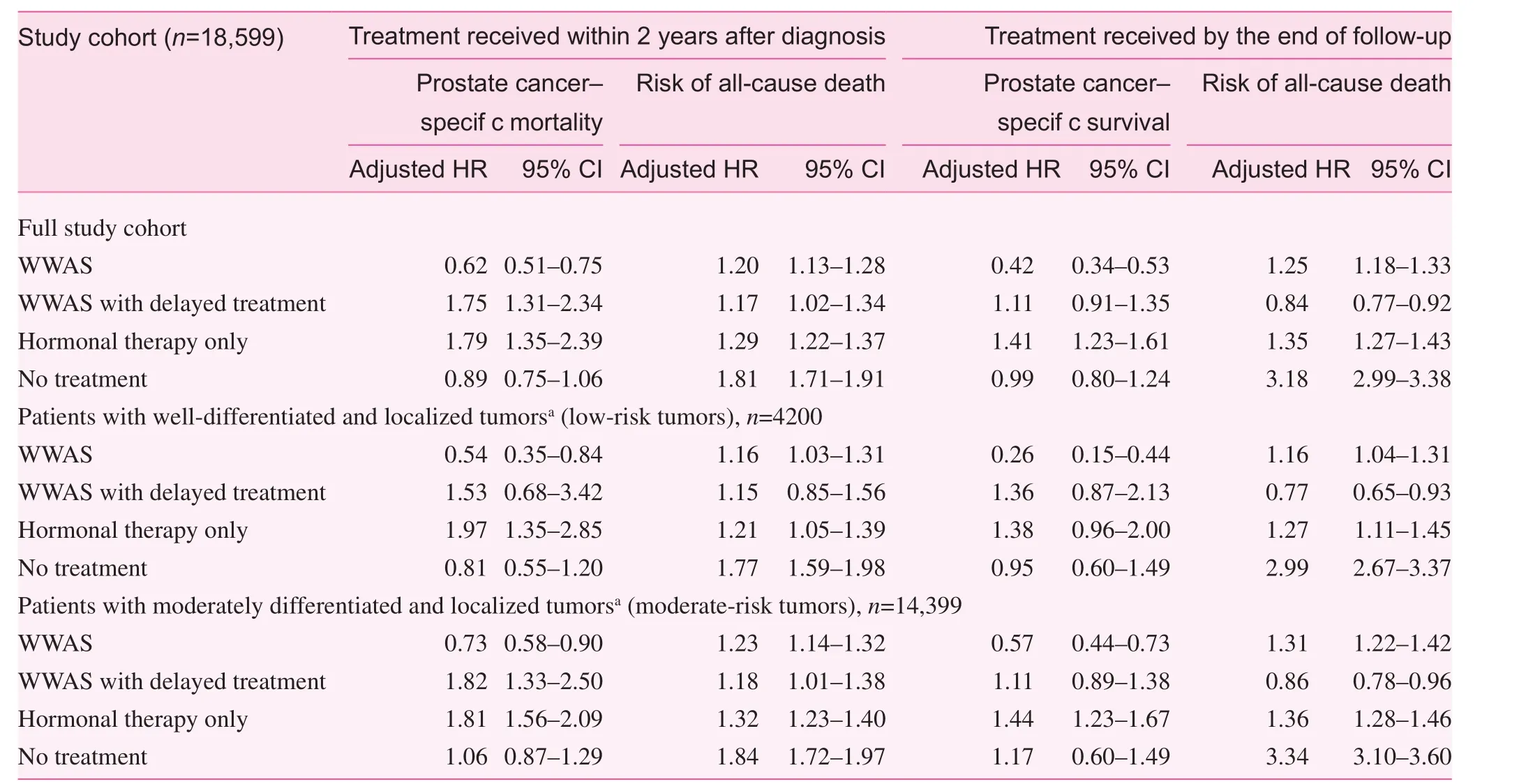

Subset matched by propensity score

We used the propensity score (the probability of receiving WWAS with or without delayed treatment) with a 1:3 matching ratio to address possible selection biases in the main analysis.The multivariable logistic model used to calculate the propensity score had aCstatistic of 0.808, demonstrating a good fit to the data. Box plots of probability values between the study groups indicated good discriminative ability before matching,and good performance of the propensity model after matching.The 1:3 matched case-control set included 4591 patients.

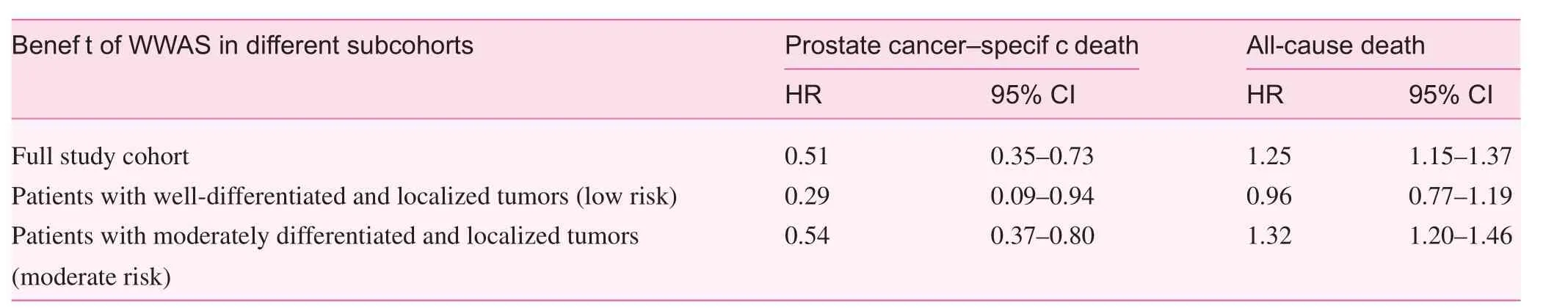

In the matched cohort, the univariate Cox proportional hazards model compared the risk of death outcomes in WWAS patients and active treatment patients. Patients managed with WWAS had a higher risk of all-cause death (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15–1.37) and a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death(HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.35–0.73) compared with active treatment patients (Table 3). In patients with early (well-differentiated,Gleason score 2–4) and localized tumors, those managed with WWAS had a slightly lower but statistically insignificant risk of all-cause death (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.77–1.19) and a substantially lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 0.29,95% CI 0.09–0.94) compared with active treatment patients.In contrast, in patients with moderately differentiated (Gleason score 5–7) and localized tumors, those managed with WWAS had a higher risk of all-cause death (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.20–1.46) and a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.37–0.80). These results are consistent with the findings from the full cohort analysis.

Table 3. Cox regression analyses in matched case-control cohort

Discussion

The benefit of radical prostatectomy in prostate cancer patients with low-risk tumors has been evaluated in both observational and interventional studies, but not often among elderly men older than 75 years [8–18]. Aggressive treatments in patients have demonstrated short-term survival benefits, but smaller differences in long-term benefits [11, 12, 15]. Aggressive treatment modalities such as radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy have known risks of complications and adverse effects on quality of life [23]. In older men with prostate cancer, competing risk from comorbidities is an important determinant of overall survival [10]. Prior observational and randomized clinical studies focused mostly on patients younger than 75 years and had very small sample sizes and statistical power to focus on those older than 75 years. Conducting a randomized controlled trial with WWAS patients as a treatment arm could pose significant ethical issues, especially in those older than 75 years at the time of diagnosis, hence the importance of observational studies to advance our understanding of the benefits of WWAS as an alternative treatment strategy in older patients with early and localized disease.

The current study focused mainly on the role of WWAS in patients older than 75 years at the time of diagnosis and presenting with less aggressive and localized tumors. The further distinction between those who received and who did not receive delayed treatment was meant to highlight the role of continued PSA-based surveillance after diagnosis. The delayed treatment could be attributed to disease progression detected by continued PSA-based surveillance. In elderly patients older than 75 years and with low-risk (well-differentiated and localized) tumors, patients who received WWAS without delayed treatment had a significantly lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death and a higher risk of all-cause death compared with patients in the active treatment group.In patients who received WWAS and delayed treatment, the risks of prostate cancer–specific and all-cause death were comparable to those of patients who received active treatment. These findings support those of other observational studies that show a very small prostate cancer–specific mortality rate and a high all-cause mortality rate. For instance in the analysis by Lu-Yao et al. [9], the data from 1992 to 2002 (early PSA era) show the 10-year prostate cancer mortality among men older than 75 years with moderate risk and managed conservatively to be only about 5%, whereas the allcause mortality was greater than 60%. In our study with up to 11 years of follow-up, the prostate cancer–specific mortality regardless of the Gleason score was 6.51% and the all-cause mortality was 54.68%.

Our study findings are also consistent with findings from randomized clinical studies that demonstrated similar or lower risks of death compared with those for active treatment [12,14]. The PIVOT trial included 731 patients from the early era of PSA-based screening, between 1994 and 2002. The trial did not demonstrate a significant long-term survival benefit in patients managed with aggressive treatment compared with patients managed by observation, regardless of the histologic features of the tumor. In the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 Randomized Trial (SPCG-4), 695 patients from 1989 to 1999 with clinically localized prostate cancer were randomly assigned to receive radical prostatectomy (n=347)or watchful waiting (n=348). In the subgroup of SPCG-4 patients older than 65 years, there was not a statistically significant difference in the risk of prostate cancer–specific death(relative risk 0.87, 95% CI 0.51–1.49,p=0.55) and all-cause death (relative risk 1.04, 95% CI 0.77–1.40,p=0.81). In this analysis, 1256 patients with early and localized disease were treated with aggressive treatment and 1076 patients were managed with watchful waiting. The watchful waiting group had a lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death (adjusted HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.84] and higher risk of all-cause death(adjusted HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31) with 5–11 years of follow-up. Even though the current study had a shorter follow-up period than the PIVOT and SPCG-4 trials, the sample size in this study is larger and the study findings are consistent with those of these two prior trials.

Even though this study had a larger sample size for patients older than 75 years compared with prior studies, it used an observational study design and had limitations. Treatment decision could be influenced by factors not captured within the construct of the linked SEER-Medicare database. Management of patients with WWAS could also be the result of various barriers to receiving aggressive treatment. Therefore, the observed benefits of WWAS in patients with early and localized disease could be confounded by selection bias. The results from the main analysis should be interpreted with caution. To address selection bias, we modeled the likelihood of patients receiving WWAS using available patient demographic and clinical characteristics in the propensity score model. The propensity score approach is designed to balance the comparison groups relative to confounding factors. The results from the matched case-control cohort are comparable with our findings in the full study cohort.

There are other limitations in this study. First, the study was limited by the lack of additional measures in the SEERMedicare database that would make it possible to describe the patients' clinical presentation in greater detail. Although the Charlson comorbidity index scores were adjusted for in the multivariate analyses to account for overall disease burden,these scores did not account for disease severity and could not be interpreted as direct measures of competing risks, and/or for the concurrent presence of functional limitations or geriatric syndromes that are likely to affect treatment decisions and outcomes. Second, the construct of linked SEER-Medicare datasets did not include information on PSA levels, and the tumor stage and grade information were summarized at the time of cancer diagnosis. As a result, our study could not use the kinetics of PSA doubling time or changes in tumor stage and grade to detect any disease progression over time. Third,since the linked Medicare records consist of administrative claims records, this study captures only reimbursed billing events related to PSA testing, but lacks data on PSA levels.Similarly, we captured DRE only when it was documented in the claims data. However, DRE may be underreported and underused, since it was not reimbursed by Medicare until 2000. Although this may have resulted in a misclassification of WWAS patients in the watchful waiting group, it is unlikely to have affected the results. Fourth, the tumor grade data in the SEER database were categorized as degrees of differentiation with the corresponding range of Gleason scores, instead of the individual Gleason score. Fifth, the study was also limited to Medicare patients with prostate cancer older than 75 years and receiving their care through the traditional fee-for-service system. As a result, the study findings may not be generalizable to patients receiving their care in managed care settings.Sixth, the study had a follow-up time window shorter than that of other studies with long-term follow-up data. Therefore,further studies are needed to evaluate the mortality outcomes over a longer follow-up period. Finally, selection bias cannot be readily dismissed from the claims data we used. Although we used propensity scores to control for potential selection bias, there may be residual confounding, and caution has to be exercised when one is interpreting our results. Definitive benefit of WWAS can be assessed only by randomized control trials with a sufficient number of patients who are 75 years or older and with a long follow-up period.

Conclusion

The findings from these analyses suggest that in patients older than 75 years with well-differentiated and localized tumors,WWAS without delayed treatment is associated with lower risk of prostate cancer–specific death but with higher risk of all-cause death compared with active treatment. In patients managed with WWAS with delayed treatment, the prostate cancer–specific and all-cause mortality outcomes were comparable to those with active treatment. Therefore, our study further supports and endorses WWAS as an initial management strategy for elderly men with low-risk prostate cancer tumors.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare administrative claims database. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development, and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the database. The authors also thank Julie Worthington,Fang Xu, and Judith Braga for their conceptual input and critical review of this study. This study was partly supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (U54 CA-116867-01 to Li Li) and the National Institute of Aging (P20 CA10373 to Li Li). Siran M. Koroukian was supported by a Career Development Grant from the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA096705). Tzuyung D. Kou is now an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb (Hopewell, New Jersey, USA).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was partly supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (U54 CA-116867-01 to Li Li) and the National Institute of Aging (P20 CA10373 to Li Li). Siran M. Koroukian was supported by a Career Development Grant from the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA096705).

1. Farwell WR, Linder JA, Jha AK. Trends in prostate-specific antigen testing from 1995 through 2004. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(22):2497–502.

2. Thompson IM, Canby-Hagino E, Lucia MS. Stage migration and grade inflation in prostate cancer: Will Rogers meets Garrison Keillor. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(17):1236–7.

3. Adolfsson J, Garmo H, Varenhorst E, Ahlgren G, Ahlstrand C,Andrén O, et al. Clinical characteristics and primary treatment of prostate cancer in Sweden between 1996 and 2005. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2007;41(6):456–77.

4. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. [cited;Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/data/.

5. Dyche DJ, Ness J, West M, Allareddy V, Konety BR. Prevalence of prostate specific antigen testing for prostate cancer in elderly men. J Urol 2006;175(6):2078–82.

6. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990–2013. J Am Med Assoc 2015;314(1):80–2.

7. Walter LC, Bertenthal D, Lindquist K, Konety BR. PSA screening among elderly men with limited life expectancies. J Am Med Assoc 2006;296(19):2336–42.

8. Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157(2):120–34.

9. Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Shih W, Lin Y,DiPaola RS, et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. J Am Med Assoc 2009;302(11):1202–9.

10. Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Gleason DF, Barry MJ. Competing risk analysis of men aged 55 to 74 years at diagnosis managed conservatively for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc 1998;280(11):975–80.

11. Wong, YN, Mitra N, Hudes G, Localio R, Schwartz JS,Wan F, et al. Survival associated with treatment vs observation of localized prostate cancer in elderly men. J Am Med Assoc 2006;296(22):2683–93.

12. Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P, Jethava V, Zhang L,Jain S, et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(3):272–7.

13. Bul M, van den Bergh RC, Zhu X, Rannikko A, Vasarainen H,Bangma CH, et al. Outcomes of initially expectantly managed patients with low or intermediate risk screen-detected localized prostate cancer. BJU Int 2012;110(11):1672–7.

14. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Garmo H, Stark JR,Busch C, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364(18):1708–17.

15. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Filén F, Ruutu M, Garmo H,Busch C, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate cancer: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(16):1144–54.

16. Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, Barry MJ, Aronson WJ,Fox S, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367(3):203–13.

17. Merglen A, Schmidlin F, Fioretta G, Verkooijen HM, Rapiti E,Zanetti R. Short- and long-term mortality with localized prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(18):1944–50.

18. Hoffman RM, Barry MJ, Stanford JL, Hamilton AS, Hunt WC,Collins MM. Health outcomes in older men with localized prostate cancer: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study.Am J Med 2006;119(5):418–25.

19. Fowler FJ Jr, Bin L, Collins MM, Roberts RG, Oesterling JE,Wasson JH, et al. Prostate cancer screening and beliefs about treatment efficacy: a national survey of primary care physicians and urologists. Am J Med 1998;104(6):526–32.

20. van As, NJ, Norman AR, Thomas K, Khoo VS, Thompson A,Huddart RA, et al. Predicting the probability of deferred radical treatment for localised prostate cancer managed by active surveillance. Eur Urol 2008;54(6):1297–305.

21. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies:development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373–83.

22. D'Agostino RB, Jr., Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998;17(19):2265–81.

23. Drummond FJ, Kinnear H, O'Leary E, Donnelly C, Gavin A,Sharp L. Long-term health-related quality of life of prostate cancer survivors varies by primary treatment. Results from the PiCTure (Prostate Cancer Treatment, your experience) study.J Cancer Surviv 2015;9(2):361–72.

Li Li, MD, PhD Department of Family Medicine-Research Division, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, 11000 Cedar Ave,Suite 402, Cleveland, OH 44106,USA

Tel.: +1-216-3685437;

Fax: +1-216-3684348

E-mail: ll134q@rocketmail.com

29 June 2015;

Accepted 26 August 2015

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- The innovations in China's primary health care reform: Development and characteristics of the community health services in Hangzhou

- Primary health care, a concept to be fully understood and implemented in current China's health care reform

- Primary care clinicians' strategies to overcome f nancial barriers to specialty health care for uninsured patients

- Disconnect between primary care and cancer follow-up care:An exploratory study from Odisha, India

- Stool DNA-based versus colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening: Patient perceptions and preferences

- Overview