Living with liver disease in the era of COVID-19-the impact of the epidemic and the threat to high-risk populations

Pranav Barve, Prithi Choday, Anphong Nguyen, Tri Ly, Isha Samreen, Sukhwinder Jhooty, Chukwuemeka A Umeh, Sumanta Chaudhuri

Pranav Barve, Department of Internal Medicine, Hemet Global Medical Center, Menifee, CA 92585, United States

Prithi Choday, Anphong Nguyen, Tri Ly, Isha Samreen, Chukwuemeka A Umeh, Sumanta Chaudhuri, Department of Internal Medicine, Hemet Global Medical Center, Hemet, CA 92543,United States

Sukhwinder Jhooty, College of Medicine, American University of Antigua, Manipal Education America’s, New York, NY 10005, United States

Abstract The cardinal symptoms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection as the pandemic began in 2020 were cough, fever, and dyspnea, thus characterizing the virus as a predominantly pulmonary disease. While it is apparent that many patients presenting acutely to the hospital with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection have complaints of respiratory symptoms, other vital organs and systems are also being affected. In fact, almost half of COVID-19 hospitalized patients were found to have evidence of some degree of liver injury. Incidence and severity of liver injury in patients with underlying liver disease were even greater. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, from August 1, 2020 to May 31, 2022 there have been a total of 4745738 COVID-19 hospital admissions. Considering the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence of liver injury in COVID-19 patients, it is imperative that we as clinicians understand the effects of the virus on the liver and conversely, the effect of underlying hepatobiliary conditions on the severity of the viral course itself. In this article, we review the spectrum of novel studies regarding COVID-19 induced liver injury, compiling data on the effects of the virus in various age and high-risk groups, especially those with preexisting liver disease, in order to obtain a comprehensive understanding of this disease process. We also provide an update of the impact of the new Omicron variant and the changing nature of COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Key Words: Liver injury; Hepatobiliary injury; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; High-risk populations; Liver disease

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to threaten the health of our communities with new emerging variants and surges in rates of infection. As the virus continues to transform and mutate, the effects severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has on various organ systems can change as well. Thus, the importance of understanding its effects on not only the respiratory system, but also extrapulmonary organ systems, becomes greater. One of the least studied systems in terms of the short- and long-term effects of COVID-19 infection is the hepatobiliary system. In this article, we review the spectrum of novel literature on hepatobiliary injury in COVID-19 and explore its relationship with various preexisting liver pathologies and special populations. Although it is a daunting task to summarize and interpret all the medical literature on this subject, we aim to provide a comprehensive review in order to address important questions regarding the effect of the virus on the liver as well as the effect of comorbid hepatobiliary conditions on mortality in COVID-19. We hope to aid clinicians and patients in gaining a better understanding of this devastating virus.

APPROACH

Articles were obtained by searching PubMed, CrossRef,Reference Citation Analysis(https://www. referencecitationanalysis.com/), and Google Scholar databases using the keywords listed in the appendix. The abstracts were reviewed to assess if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be included in the review. To be included in the review, the articles must have been about COVID-19 and hepatobiliary disease and must have been written in English. Case reports were excluded from the study.

Ultimately, we identified 56 articles that met the inclusion criteria. These articles were analyzed and summarized in this review. The hepatobiliary diseases reviewed in this article include liver cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) syndromes, post-liver transplantation, and hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) co-infections. Special populations include patients who had the following characteristics- pregnancy, obesity, racial minorities, and diabetes.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND TYPES OF LIVER INJURY IN COVID-19

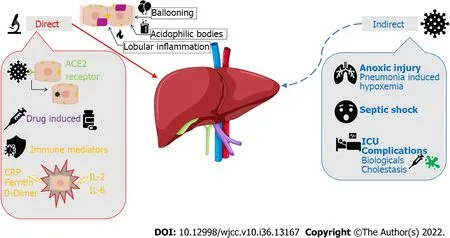

The pathophysiologic effects of COVID-19 on the hepatobiliary system are still under debate. However, there have been studies that have evaluated the possible mechanisms of injury, both direct and indirect as illustrated in Figure 1. Direct viral injury of hepatobiliary damage is evidenced by liver biopsy findings of ballooned hepatocytes, acidophilic bodies, and lobular inflammation. Three plausible mechanisms can explain the pathophysiology of direct liver injury caused by SARS-CoV-2. The first mechanism is initiated by viral binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on target cells of epithelial cholangiocytes and hepatocytes as a means of entry into these cells[1]. Viral entry and replication within these cells leads directly to cytotoxicity. The second mechanism is primarily immunemediated. Immune dysfunction accompanying COVID-19 disease progression, including both lymphopenia or immune system upregulation, can independently lead to hepatic cytotoxicity[1]. Severity can be correlated with the degree of elevation in inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-2[2]. The third mechanism involves drug-induced liver injury from common drugs used in COVID-19 management. Specifically, the COVID-19 medications with known hepatotoxic effects include ritonavir, remdesivir, chloroquine, tocilizumab, and ivermectin[2].

Figure 1 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and its pathophysiological effects on the hepatobiliary system. ACE2:Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; IL: Interleukin; CRP: C-reactive protein; ICU: Intensive care units.

The hepatobiliary system can also be affected indirectly through the downstream effects of COVID-19 infection. Patients with severe hypoxia and hypoxemia from COVID-19 pneumonia can sustain anoxic injury of major extrapulmonary organs, including the liver[3]. Sepsis with hypotension can also cause liver injury due to poor perfusion. Additionally, critically ill patients (i.e., patients requiring Intensive Care Unit admission) are more prone to liver dysfunction as they may require life-saving hepatotoxic drugs, such as high-potency antibiotics, amiodarone, propofol, antiepileptics, and parenteral nutrition. These patients may experience cholestasis due to inflammatory cytokines that can impair bile acid secretion and absorption. SARS-CoV-2 can also cause reactivation of existing metabolic liver or biliary diseaseviaimmunologic processes or drugs. Biologic drugs used in COVID-19 treatment, such as tocilizumab and baricitinib, can lead to HBV reactivation. SARS-CoV-2 may also exacerbate cholestasis in those with underlying cholestatic liver disease.

DELTA VS OMICRON VARIANTS OF COVID-19

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, we have learned of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants with predominance during different periods of time. Understanding the differing hepatobiliary effects of individual variants is of great importance as new surges of the virus are often brought on by the emergence of a new variant, and viral characteristics among the variants differ. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention data, the dominant variant from March 2021 to June 2021 was the Alpha variant, with a drift to the Delta variant from June 2021 to December 2021[4]. Omicron variant predominance occurred during December 2021 and continues to this day as various sub-variants of Omicron have emerged. Our literature search revealed only two studies focused on the liver injury caused by different variants of COVID-19. In a prospective cohort study by Denget al[5], 157 SARSCoV-2 infected patients on hospital admission were enrolled, of which 77 patients were infected with Delta variant and 80 patients were infected with Omicron variant[5]. Mild liver injury was found in 23.4% of Delta-infected patients and 18.8% of Omicron-infected patients. In contrast, cholangiocyte injury was found in 76.5% of Delta-infected patients and 83.3% of Omicron-infected patients. While the numbers are staggering, there is no significant difference in this group’s rates of hepatobiliary injury. In a study by Jang[6], no difference in liver injury was noted between Delta and Omicron variants[6]. They do note that the prevalence of the COVID-19 vaccine during the Omicron variant-dominant era may likely play a role in this. However, there is insufficient data on the isolated effects on the hepatobiliary system of the different variants, and further study of this subject is warranted.

CO-MORBID HEPATOBILIARY CONDITIONS: LIVER CIRRHOSIS

The interplay between COVID-19 and liver cirrhosis has yet to be precisely characterized. On review of data gathered from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), 30-d survival of COVID Positive/Non-Cirrhotic patientsvsPositive/Cirrhotic patients had statistically significant differences wherein Positive/Cirrhotic Patients had 2.38 times mortality hazard at 30 d[7]. Moreover, data gathered from SECURE-Cirrhosis and COVID-Hep registries suggest an association between increased mortality and rates of mechanical ventilation with higher Child-Pugh classes. Specifically, Class A was associated with a 1.9 odds ratio of death, Class B with 4.14, and Class C with 9.32. Of note, patients who survived acute COVID-19 infection returned to baseline mortality associated with liver cirrhosis alone[8].

Overall, the data suggest underlying liver cirrhosis and chronic liver disease (CLD) are risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection and death. To further stratify these patients, increasing severity of underlying liver disease as characterized by Child-Pugh class is associated with an increased risk of morbidity. The underlying immunologic processes that can perhaps explain this phenomenon may be found in the decreased T cell response to vaccination in cirrhotic patients, as well as a > 50% reduction in Cluster of Differentiation 8 response to omicron infection that has been noted in patients with cirrhosis when compared to patients without cirrhosis, which puts this population at even higher risk of severe disease[9,10].

CO-MORBID HEPATOBILIARY CONDITIONS: SSC

There is a subset of COVID-19 patients with liver injuries who may also be at increased risk of developing SSC secondary to infection with SARS-CoV-2, generally evidenced by elevated bilirubin in the setting of typical imaging or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography findings. Several case reports and case series have suggested the possibility of a connection between COVID-19 infection and the development of SCC[11-13]. One multicenter retrospective study of 127 patients diagnosed with SSC identified 16.7% of the patients as having a recent COVID-19 infection[14]. In a recent retrospective study published in theJournal of Hepatologyby Hartlet al[15], researchers compared liver injury parameters between patients admitted for COVID pneumoniavsthose admitted for non-COVID pneumonia[15]. They found that patients with CLD and COVID-19 pneumonia had increased rates of prolonged and progressive cholestasis and cholestatic liver failure. Additionally, in their study, 15.4% of patients with CLD (10/65) developed SSC in COVID pneumonia compared with 4.6% (3/65) in patients with CLD and non-COVID pneumonia (P< 0.05). Patients with NASH/NAFLD were also at increased risk of developing SSC after COVID-19. These results suggest a connection between COVID-19 infection and the development of SSC. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the pathophysiology and mechanism for this phenomenon.

CO-MORBID HEPATOBILIARY CONDITIONS: AIH

AIH is an immune-mediated disorder of unclear etiology. Triggers include infections, medications, and toxins. Upon review of selected articles, an increased incidence of AIH following COVID-19 vaccination was noted. A retrospective meta-analysis by Chowet al[16] found that a rare adverse event which presented as AIH -like syndrome was seen after receiving COVID-19 vaccinations[16]. A total of 32 cases of COVID-19 vaccine-induced AIH-like syndromes were identified. These patients typically presented with jaundice (81%), and approximately 19% of patients were asymptomatic and presented with elevated liver enzymes detected during routine blood work. Antinuclear antibody was positive in 56% of patients and anti-smooth muscle antibody was positive in 28%. The prognosis of AIH secondary to COVID-19 vaccination is excellent, and complete resolution was seen in 97% of patients, of which 75% had received steroids.

Subsequently, upon further literature review, a case series showed an association between COVID-19 infection and the development of AIH[16]. Potential antigenic cross-reactivity exists between SARSCoV-2 and human tissue, which increases the possibility of development of autoimmune disease after COVID-19 infection. The study showed that antibodies against the spike protein S1 on SARS-CoV-2 had a high affinity for human tissues (transglutaminase, Myelin basic protein)[16]. In previously published case reports, most patients who developed these antibodies were female, aged 35 to 80. One particular case report we reviewed involved a 61-year old female with underlying history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and hypertension who developed AIH 1 mo after administration of the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine. She presented with a constellation of symptoms including: malaise, anorexia, nausea, and scleral icterus for two weeks. The patient has no history of liver disease or alcohol abuse, nor has used any hepatotoxic drugs or supplements. She was diagnosed with mild COVID-19 infection 8 mo prior and received the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine one month prior. Laboratory studies were significant for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 455 IU/mL [upper limit of normal (ULN) 55 IU/mL]; aspartate aminotransferase 913 IU/mL (ULN 34 IU/mL); gamma glutamyl transferase 292 IU/mL (ULN 36 IU/mL); alkaline phosphatase 436 IU/mL (normal range: 40–150 IU/mL); total bilirubin 11.8 mg/dL (ULN 1.2 mg/dL); direct bilirubin 9.18 mg/dL (ULN 0.5 mg/dL) along with positive anti-nuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibody titers. Upon diagnosis, the AIH patient was given prednisone and had complete resolution of her liver function abnormalities. Most patients presenting with AIH post COVID-19 vaccinations had similar age, presentation, and laboratory values as the case discussed above. This particular case used a simplified AIH score to diagnose the patient. The use of such a scoring system would prove to be efficacious in patients presenting with AIH symptoms post- COVID-19 vaccination[17].

Individuals with preexisting AIH and interactions with COVID-19 infection were another population that was reviewed. A retrospective multicenter cohort study in Europe and the Americas studied the severity of COVID-19 infection in patients with CLD with and without preexisting AIH[18]. To limit bias, the patients with AIH were compared to a propensity score–matched cohort of COVID-19 patients without AIH but with CLD. The study included 110 AIH patients, of which 80% were female, with a median age of 49. Twenty-nine percent of the patients with AIH already had features of liver cirrhosis prior to the COVID-19 infection. They observed new-onset liver injury in 37.1% of the patients and found that continued use of immunosuppressants during COVID-19 was associated with a lower rate of liver injury at an odds ratio of 0.26 (95%CI: 0.09-0.71,P= 0.009)[18]. However, the use of antivirals was associated with new-onset liver injury with an odds ratio of 3.36 (95%CI: 1.05-10.78,P= 0.041)[18]. Interestingly, there was no difference in the rates of severe COVID-19 and all-cause mortality between AIH and non-AIH CLD patients. Based on this study, the maintenance of immunosuppressive therapy in COVID-19 patients with AIH did not increase the severity of COVID-19 disease but lowered the rate of new-onset liver injury. This is in contrast to the use of antiviral agents that have been found to be associated with new-onset liver injury[18]. However, caution should be exercised in describing a causal relationship between these factors, as an exact mechanism has yet to be fully explored.

CO-MORBID HEPATOBILIARY CONDITIONS: NAFLD/NASH

The United States is currently experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic, while also suffering from an epidemic of NASH. Many common comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, have been widely studied and shown to play a role in COVID-19 mortality. Metabolic syndromes like NAFLD and its sequelae, NASH, should also be considered among these comorbid conditions as their prevalence is rapidly rising. Liver injury and subsequent fibrosis caused by the accumulation of fat in the liver could exacerbate the cytokine storm associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, possibly leading to poor outcomes in these patients[19]. This can be evidenced by the presence and degree of liver injury with poorer outcomes in the NAFLD/NASH population compared with the general population infected with SARS-CoV-2. In our literature search, we found five studies that have evaluated the effect of underlying NAFLD on COVID-19- induced liver injury and mortality. The first is a prospective cohort study that concluded that NAFLD diagnosis was not associated with worse outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19[20]. However, the NAFLD group of patients had a higher average C-reactive protein level compared with the non-NAFLD group, suggesting that there was a more pronounced inflammatory response in the NAFLD group. The second study used the NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) in 86 patients with COVID-19 and underlying NAFLD to determine its association with COVID-19 mortality[21]. 44.2% of these patients had advanced liver fibrosis, according to the NFS. It was shown that there was a statistically significant association (P< 0.05) between advanced NFS score and severe illness from COVID-19 in these patients compared with the general population. Through a pooled analysis, the third study found that NAFLD was associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19, even after adjusting for obesity as a possible confounder[19]. The fourth study used Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) scores of a cohort of 310 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection and NAFLD to determine their association[22]. The authors concluded that the severity of COVID-19 illness was markedly increased among patients with NAFLD and intermediate to high FIB-4 scores. Using large-scale TSMR analyses and genome-wide meta-analysis of the United Kingdom biodata bank, the last study determined that there was no causal relationship between NAFLD, serum ALT, grade of steatosis, NAFLD Activity Score, and fibrosis stage with severe COVID-19[23]. The emergence of the NAFLD epidemic and the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic greatly emphasize the importance of understanding these conditions together through further studies.

CO-MORBID HEPATOBILIARY CONDITIONS: LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Patients with solid organ transplants are a special population to be considered in the setting of COVID infection due to their immunosuppressant medications. Of particular interest to our review are patients who have undergone liver transplantation. While limited in quantity, data reviewed from COVID-Hep, SECURE-Cirrhosis registries suggest that transplant recipients faced an approximately 37.5% fatality rate[24]. However, another Spanish prospective cohort study found that these patients had similar fatality rates to control groups[25]. Overall, these differences in study findings suggest poor statistical power as data on these populations is not readily available.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS: PREGNANCY

Liver dysfunction affects approximately 3% of all pregnant women and has been linked to premature delivery, low birth weight, and stillbirth[26]. Recent literature suggests that the incidence of more severe liver disease in pregnancy, such as acute fatty liver of pregnancy and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome, is higher than previously reported[27]. This is further complicated by the increased incidence of liver disease in pregnancy patients with concurrent COVID-19 infection. Possible mechanisms of liver injury in these patients include multiorgan microvascular injury, sequelae of a genetic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation disorder, or a purely immunological process[28]. An immunologic process wherein elevated IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha could contribute to endothelial dysfunction and genetic polymorphisms of toll-like receptor 4 and, in turn, could dysregulate maternal inflammatory processes, may explain or partially explain the observation[29]. Understanding this process is important in understanding the possible effect of COVID-19 as an inciting or confounding factor for liver injury during the peripartum period. In a 2020 double cohort study, Chaiet al[30] discussed SARS-CoV-2 virus affinity for ACE2 on cholangiocytes, resulting in subsequent dysfunction of liver regeneration and immune responses[30]. COVID-19 infection has been reported to increase the risk of pregnancy complications such as eclampsia, preeclampsia, and HELLP syndrome[31]. In a retrospective study, Denget al[32] reported a 29.7% prevalence of liver injury in pregnant women who were infected with SARS-CoV-2[32]. A meta-analysis also showed significantly increased odds of developing HELLP syndrome in pregnant patients with COVID-19 compared to those who did not have COVID-19 infection[33]. The pathophysiology of the effect of COVID-19 on liver function is still unclear but may be linked to an immunologic process, as mentioned above. The studies reviewed in our literature search almost unanimously concluded that there is an increased incidence and severity of maternal and fetal complications amongst pregnant women with COVID-19.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS: OBESITY

Obesity is a known independent risk factor for COVID-19. Metabolic syndrome is associated with poor outcomes related to liver injury in COVID-19. We reviewed six articles concerning liver injury in obese patients with COVID-19. While there were many articles on the effect of metabolic syndrome on liver injury in COVID-19, many did not study the isolated role of obesity in liver injury from COVID-19. Ultimately, we had three articles that met our inclusion criteria in this review. A retrospective analysis of COVID-19 patients admitted to a hospital in Northern Italy revealed that 18.6% of the obese COVID-19 patients had liver injuries[34]. These numbers appear to be higher in those with underlying metabolic syndrome, especially those with NAFLD, due to an inflammatory mechanism of injury, as discussed earlier in this article. Mechanisms of liver injury in obese patients with COVID-19 may derive from the adipocytes themselves and/or from secondary syndromes of obesity. Adipocytes have similar functions to immune cells and produce inflammatory mediators, which in conjunction with the cytokine storm from SARS-CoV-2, may contribute to superimposed direct injury of the liver and other organs[35]. Sleep apnea syndrome caused by obesity can lead to hypoxia and subsequent anoxic injury to the liver[36]. However, more studies need to be conducted on this subject to definitively note the role of obesity in liver injury in COVID-19 patients. The effects of the environmental and habitual changes, including social distancing, sedentary lifestyles, and school and work closures brought out by the pandemic must also be taken into account. According to a retrospective study by Gwaget al[37] of school-aged children in Korea, the proportion of children who were overweight or obese increased from 24.5% at the COVID-19 pandemic baseline to 38.1% 1 year later[37].

SPECIAL POPULATIONS: RACIAL DISPARITIES

COVID-19 affects certain racial groups differently, especially within the Hispanic and African American communities. There were various studies that explored the effects and aftermath of the COVID-19 infection in diverse groups. A microsimulation study was done to estimate individual risks using data collected from the Health and Retirement Study, Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services[38]. The study used the future elderly model and the future adult model and had a target population of United States individuals aged 25 years and older who had COVID-19 through March 13, 2021. The study found that Black and Hispanic persons greater than or equal to 65 years of age had a disproportionate share of the mortality burden, though they had a lower age-adjusted life expectancy. The study showed Hispanic men aged 65 years or older lost an average of 2.5 times more quality of life yearspercapita compared to similarly aged white men. Hispanic men aged 25 to 64 lost three times more quality of life years than other men in the same age group[38].

A recent cohort study across twenty-one American institutions involving over nine hundred United States adults with CLD and polymerase chain reaction confirmed COVID-19 showed that Hispanic Americans (25.5%) and African Americans (31.4%) were disproportionately affected[39]. These two racial minorities comprised over half (56.9%) of the hospitalized group compared to the racial majority of Non-Hispanic Whites (33.8%). The most likely root cause is multifaceted. Hispanic CLD patients were not only majority female (50.4%) but also happened to be the youngest on average. African American CLD patients had a significant prevalence of hypertension (70.1%)[39]. These findings were also evident in another retrospective study which showed that African Americans had a statistically significant increased risk (odds ratio: 2.69) of hospital admission with underlying NAFLD and COVID-19[40]. Another study in New Mexico indicated that Native Americans (NA) had an 11-fold increase in the risk of COVID-19 related hospitalizations compared to Non-Hispanic Whites, in which 77% of NAs had underlying CLD[41]. One variable to consider would be differences in socioeconomic variables amongst the Hispanic and African American groups in this study. White Americans tended to have higher rates of private insurance, while the majority of African and Hispanic Americans were enrolled in Medicaid/Medicare. White American patients tended to reside in single-family homes with an average of 1-2 residents, while Hispanic patients tended to live in multi-family homes with 5+ residents on average. In this study, both African and Hispanic Americans, on average, lived in lower-income households. The same socioeconomic discrepancy that affected Hispanics and African Americans was paralleled in the Native American population, such as crowded homes, lower-income households, and increased comorbidities such as diabetes and CLD[41].

Analyzing these studies suggests that various socioeconomic factors put certain minority groups with CLD at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and subsequently requiring hospitalization. Over time, further studies need to be conducted to accurately assess the life years lost with each racial group in patients with CLD and COVID-19 infection.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS: DIABETES

Several studies have shown an association between diabetes and increased risk of COVID-19 severity and increased in-hospital mortality[42]. Other studies have also found evidence that diabetic patients who contract COVID-19 are at increased risk for liver injury. In a retrospective cohort study by Phippset al[43], 16.7% of patients with diabetes developed elevated transaminases greater than two times the upper limits of normal[43]. Another study by Kumaret al[44] showed that up to 73.3% of COVID-19 patients with diabetes developed liver injuries[44]. Another recent study by Singh and Khan observed that many diabetic patients who contracted COVID-19 also have pre-existing liver disease (48% of the total of 2780 patients)[45]. This study reveals a complex relationship between patients with diabetes with pre-existing liver injury and the development of acute liver injury from COVID-19 infection.

CO-INFECTION

Since the first reported case in December 2019, the understanding and treatment of COVID-19 has experienced numerous developments. Immunosuppressants and steroids have become the leading modalities of treatment after our understanding of the pathogenesis and patient outcomes related to the cytokine-mediated immune response from the virus has evolved. However, the use of immunosuppressants and steroids to treat COVID-19 becomes a double-edged sword as patients under treatment experience reactivation of underlying chronic HBV and HCV virus infection[46]. An American study estimated that the mortality of known liver disease patients with COVID-19 was 12% compared to 4% in COVID-19 patients with no liver disease[45]. Simultaneously, a United Kingdom National Health Science study estimated that CLD was a risk factor in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.39 (95%CI: 2.06-2.77)[47].

CO-INFECTION: HBV

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are 296 million individuals living with the HBV. Recent studies show that concurrent HBV and COVID-19 infections have led to worse outcomes for patients due to the increased risk of developing acute-on-chronic liver failure. One small retrospective study of 105 patients in China concluded that the increase in mortality among liver injury patients was 28.57%vs3.30% in non-HBV COVID-19 positive patients[48]. Another study involving HBV-Core antibody-positive patients showed that the risk of a hepatitis flare (ALT > 80 U/L) increased with corticosteroid 20 mg dose (HR: 2.19,P= 0.048) and 40 mg dose (HR: 2.11,P= 0.015) respectively[49]. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease currently recommends that patients who are COVID positive and develop an acute hepatitis flare should undergo treatment promptly with antivirals[24]. A recently published clinical case review suggested that all RNA-positive COVID-19 individuals be screened for HBV markers prior to starting any treatment regiments as both may have compounding effects. If the patient is HBV surface antigen-positive, they should be prophylactically treated with entecavir and tenofovir (Disoproxil and Alafenamide) for 12 mo with routine HBV DNA testing every 3 mo. Those who are HBV surface antigen-negative or HBV core antibody negative should be viewed as low risk and monitored for any reactivation and subsequently treated with nucleotides[50].

CO-INFECTION: HCV

It’s estimated that there are roughly 58 million people worldwide with chronic HCV. Since its discovery in 1989; routine testing and screening have become standard practice for any procedure involving blood transfusion, blood products donation, and assessment of high-risk individuals, such as prisoners, drug users, and health care workers. WHO estimates that roughly 70% of acute HCV infections will continue onto chronic HCV infections, while 30% will spontaneously resolve within six months. Chronic HCV is highly concerning as patients develop liver cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma, which leads to approximately 290000 deaths worldwide in 2019[51]. Antiviral treatment has a 95% cure rate; however, the limiting factor is the lack of proper access to diagnosis and treatment. Preliminary results from an International Registry showed that patients with decompensated cirrhosis and COVID-19 had additional liver function deterioration leading to a mortality rate of 43%-63%[52]. Therefore, a recent Italian Joint Association statement called Alliance against Hepatitis recommends starting joint HCV/COVID-19 screening, allowing for prompt HCV treatment[53]. However, if the patient is COVID-19 positive, it is recommended that direct-acting antivirals for treating chronic HCV be deferred until they test negative for the COVID-19 vital antigenvianasopharyngeal swab[54].

All these factors will need to be studied further to assess if the WHO Global Hepatitis initiative to eliminate viral hepatitis globally by 2030 is still feasible. One annual global model outcome study involving 110 nations concluded that a single-year delay in viral hepatitis elimination led to an additional 44800 deaths due to Hepatocellular Carcinoma and 72300 hepatic-related deaths over the next 10 years[55]. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems have drastically reduced the critical screening protocols for viral hepatitis, thus leaving more patients undiagnosed with hepatitis. However, with the recent policy and healthcare system changes, the mass-testing and telemedicine infrastructure stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic could ultimately help to curb viral hepatitis.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF RESEARCH

In our review of current literature, it appears that a complex relationship exists between COVID-19 and the development of hepatobiliary injury. However, a clear causative relationship remains unclear, and higher quality studies are required to better characterize the relationship between COVID-19 and its effects on the hepatobiliary system. Future research must answer the question of whether hepatobiliary comorbid conditions lead to worsening liver injury in COVID-19 patients or COVID-19 infections lead to acute and chronic liver injury regardless of underlying comorbidities. For example, a future study design can compare COVID-19 patients with mild, moderate, and severe CLD with patients with no prior diagnosis of CLD and determine the rates of liver injury in each group to assess if a linear relationship exists between CLD and the development of liver injury in COVID-19 patients.

Another significant area of research that may provide valuable insight into viral pathology is differentiating the effects of COVID-19 variants on hepatobiliary injury to help clinicians and researchers predict the pathophysiology of future variants and sub-variants. A simple clinical query into the difference in the development of liver injury in patients infected with the delta variant compared to those infected with the omicron variant could be conducted to provide more insight.

Additionally, further studies are necessary to determine the contribution of co-morbid conditions to the difference in morbidity and mortality observed between ethnic minorities and their White American counterparts. Future studies should consider including racial ethnicities/minorities when analyzing liver injury due to COVID infection.

CONCLUSION

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many studies have been conducted to characterize and understand the effects of this virus. Aside from causing derangements in the respiratory system, the virus appears to have the ability to affect multiple organ systems. As case reports, case series, and multiple high-quality studies have emerged, mounting evidence shows a relationship between COVID-19 infection and the development of liver injury and hepatobiliary-related disease entities. A general concept of the possible pathways from COVID-19 infection to liver injury has been described[1,2]. However, it remains unclear which pathophysiologic pathway is the predominant mode through which COVID-19 infection leads to liver injury.

Perhaps not surprisingly, multiple studies have linked patients with pre-existing hepatobiliary conditions such as cirrhosis of the liver, NASH/ NAFLD syndromes, AIH, and liver transplant recipients as being at increased risk for developing acute and chronic liver injury from COVID-19 infection. Similarly, patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy have also been shown to be predisposed to liver injury from COVID.

One interesting finding in recent COVID-19 research is the discovery of a relationship between COVID-19 infection and the development of SSC. While most studies have been case reports and case series, our review showed that some recent high-quality studies have added supporting evidence to this potential relationship. Specifically, recent studies have suggested that patients with CLD who develop severe COVID-19 are also at increased risk of developing SSC[15].

Our review further suggests that racial disparities exist between minorities (African Americans, Hispanics, NA) and White Americans in terms of morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19 infection. Although the underlying reason is complex and multifactorial, some studies have shown that minority populations are more likely to have comorbid hepatobiliary conditions, obesity, and diabetes that predispose them to acute and chronic liver injuries. Further studies are needed to characterize this complex relationship, and to describe the contribution of social determinants of health to the development of severe COVID disease and liver injury.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Each author was involved substantially in the creation, review and revision of this manuscript; The order sequence represents the degree of involvement for each author; Barve P contributed to the editing, guidance, supervision; Choday P contributed to the data collection, writing, editing, organizing; Nguyen A contributed to the data collection, writing, editing; Ly T and Samreen I contributed to the data collection, writing; Jhooty S contributed to the data collection, writing, illustration; Umeh C contributed to the data collection, editing, guidance; Chaudhuri S contributed to the editing, guidance, supervision.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORCID number:Pranav Barve 0000-0002-3490-1451; Prithi Choday 0000-0003-2785-0956; Isha Samreen 0000-0003-4035-5562; Chukwuemeka A Umeh 0000-0001-6574-8595.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Precautions before starting tofacitinib in persons with rheumatoid arthritis

- Hoffa's fracture in a five-year-old child diagnosed and treated with the assistance of arthroscopy: A case report

- Development of dilated cardiomyopathy with a long latent period followed by viral fulminant myocarditis: A case report

- Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus arginine vasopressin receptor 2 gene mutation at new site: A case report

- Short-term prone positioning for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome after cardiopulmonary bypass: A case report and literature review

- Compound heterozygous p.L483P and p.S310G mutations in GBA1 cause type 1 adult Gaucher disease: A case report