Current status of disparity in liver disease

Tomoki Sempokuya,Josh Warner,Muaataz Azawi,Akane Nogimura,Linda L Wong

Abstract

Disparities have emerged as an important issue in many aspects of healthcare in developed countries and may be based on race, ethnicity, sex, geographical location, and socioeconomic status. For liver disease specifically, these potential disparities can affect access to care and outcome in viral hepatitis, chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Shortages in hepatologists and medical providers versed in liver disease may amplify these disparities by compromising early detection of liver disease, surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma, and prompt referral to subspecialists and transplant centers. In the United States, continued efforts have been made to address some of these disparities with better education of healthcare providers, use of telehealth to enhance access to specialists, reminders in electronic medical records, and modifying organ allocation systems for liver transplantation. This review will detail the current status of disparities in liver disease and describe current efforts to minimize these disparities.

Key Words: Disparity; Transplant; Race; Age; Gender; Hepatitis

INTRODUCTION

In 2017, an estimated 1.5 billion people worldwide had some type of chronic liver disease, and this increased by nearly 35% from the previous decade[1]. About 60% of this chronic liver disease was due to non-alcoholic fatty liver, while 38% was due to viral hepatitis and 2% due to alcohol-related liver disease. Both acute and chronic liver diseases are prevalent worldwide, but the specific etiology of liver disease has geographic variations based on underlying risk factors[2]. In general, viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, is more common in Asian and African countries. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is more common in North American and Latin American countries due to a high prevalence of obesity. In addition, underlying genetic factors, such as the Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) allele, may contribute to a different phenotype of liver disease[3].

However, the true prevalence of liver disease may be a function of the health care providers available to make these diagnoses. A study from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD)’s workforce study group reported a critical shortage of hepatology providers[4]. They identified about 8000 gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and advanced practice providers who had practices in which ≥ 50% of their time was spent in hepatology. Their modeling analysis predicted that by 2033, the United States would have 35% fewer hepatology providers than needed to care for the population. As the recognition and management of the liver disease can be complex and often require specialized care, patients with liver disease will be at risk of receiving suboptimal care based on accessibility to hepatologists. This review will discuss the studies to characterize the current status of disparities in liver disease and describe current efforts to minimize disparities.

VIRAL HEPATITIS

Hepatitis A, B, and C viruses (HAV, HBV, and HCV, respectively) are the most common causes of viral hepatitis. Hepatitis Delta is less common and tends to occur as a coinfection with HBV. Hepatitis E, though less common than the others, is similar to HAV as it is transmitted via the fecal-oral route. HBV is primarily transmitted vertically, especially in Asian countries, but like HCV, this can be transmitted with direct blood contact from transfusions, intravenous drug use, other needle stick injuries, tattoos, or sexual contact. The incidence of these viruses varies based on geographic and socioeconomic factors, but there are also disparities in access to the prevention and treatment of these viruses. Outcome may also differ by race as Asians had higher HBV mortality while non-Hispanic Whites had increased HCV mortality despite the decrease in all other ethnic groups[5].

Disparities in vaccination

Prevention of these viruses can be accomplished with vaccination, proper screening of the blood supply for transfusion, minimizing food contamination and public education. Only HAV and HBV can be prevented with appropriate vaccines. Access to immunizations may be limited by geographic and socioeconomic factors, and populations affected by this disease prevention disparity may be at an increased risk for HBV infection. A descriptive epidemiologic study in rural China showed that HBV vaccination was more likely among those in higher income quintiles, higher education levels, and nonfarm occupations[6]. A cross-sectional study from South Korea evaluated HBV vaccination rates among the homeless population, finding only 39.8% completed their HBV vaccination series[7]. In the United States (U.S.), other factors decrease the probability of vaccination, including the vaccine costs, service fees, travel costs, the time required to receive a vaccine, and older age. Overall, income was the single greatest variable affecting HBV vaccination inequality, with a relative weight of > 52%[8]. Advanced age, lower income, a lack of private insurance, and lower education levels have a marked negative influence on the completion of immunization[7]. Residing within an urban area was associated with a higher compliance rate with completing the vaccinations. Clearly, the availability of vaccinations alone is not enough to ensure universal protection by immunization.

Disparities in screening for viral hepatitis

Proper identification of patients with viral hepatitis may also depend on access to care. More than 80% of HBV in the U.S. were not diagnosed, and 40% of patients with HCV in the U.S. from 2015-2018 were unaware that they had this infection[9]. Currently, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommends a one-time HCV screening for all adults aged 18 or older and for all pregnant women during each pregnancy. A systematic review of 19 studies reported that screening for HCV in the general population was variable in terms of cost-effectiveness[10]. However, screening intravenous drug users, pregnant women, HIV-infected, and certain immigrant populations may be more consistently cost-effective. For HBV, the AASLD recommends screening of HBV for persons born in areas in which HBV is endemic, pregnant women, dialysis patients, or those with high-risk behavior, including intravenous drug use[11].

However, there are barriers to successful HBV screening in Asian and Pacific Islander (API) communities, including cultural beliefs of wellbeing, misinformation about HBV, and lack of access to culturally sensitive healthcare[8].

Disparities in treatment of viral hepatitis

While community campaigns can promote screening for viral hepatitis, screening can only be truly effective if there is an appropriate linkage to care. Of the estimated 700000 people with HBV in the U.S., only 15% are aware of their diagnosis, and only 4.5% are receiving treatment[12]. While HCV infection is not preventable with vaccination, it is curable with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications. However, the high cost of these medications may have further exacerbated disparities in HCV care. In a large cohort of 29544 patients with HCV in 4 different health care systems, older age and enrollment in commercial insurance correlated with increased rates of HCV treatment[13]. Patients not receiving treatment had more comorbidities, including HIV, mental health disorders, and non-HCC cancers. Additionally, the Hispanic race and those with Medicare, Medicaid, and indigent care/no insurance were significantly less likely to receive treatment. Even after access to DAAs improved (after 2014), the treatment of chronic HCV remained low at < 20%, and patients who were Hispanic and with publicly funded or no insurance were less likely to receive treatment[13]. Jung et al[14] found socioeconomic disparities in prescribing patterns for DAA medications among Medicare patients. Schaeffer et al[15], in exploring low HCV treatment rates among underserved African Americans in San Francisco found that most of those not receiving treatment were lost to follow-up before eligibility was determined.

Other potential disparities

Other factors that affect the diagnosis and progression of viral hepatitis that may potentially be perceived as disparities include gender, genetic factors, diet, environment/geography, and other patient comorbidities. Higher rates of specific circulating microRNAs, which may increase disease progression, were found in Black patients diagnosed with HCV-mediated HCC and cirrhosis[16]. This may be a contributing factor to the high prevalence of chronic HCV in this population. An ecologic study done in New York City demonstrated a geographic disparity in HCV-related mortality[17]. Neighborhoods with higher proportions of Hispanic and Black residents, poverty, non-English speaking households, and/or lower mean education level were positively associated with HCV mortality. Women with HCV also had a lower fibrosis score at younger ages, but this disparity does not persist after 50 years of age[18]. Rates of fibrosis progression were also highest among women with low socioeconomic status and among those with HIV coinfection. This population is also less likely to achieve sustained virologic response (SVR). However, racial disparities can be eliminated once SVR is achieved in terms of liver disease progression and overall survival[19].

Vulnerable populations

Vulnerable populations have been the focus of numerous efforts aiming to understand and address the disparities in the prevention, screening, and treatment of viral hepatitis. Incarcerated individuals are particularly susceptible to viral infections both chronically and acutely. Worldwide, the prevalence of HCV is 10%-30% in prisoners, with an overall prevalence of 17.7%[20]. In 2019, an HAV outbreak occurred at a county jail in Minnesota, U.S.[21]. In response, the county jail’s health service promoted HAV vaccination among inmates, increasing vaccination from 0.6 to 7.1% within three days. Homeless individuals are another vulnerable population with limited access to appropriate healthcare. HCV screening in 6767 homeless individuals in Los Angeles, California, identified that 11.4% were HCV antibody positive. More than half of these patients were viremic, but 95% of the viremic patients were treated successfully with resources that were accessible within the local community[22]. A study in New South Wales, Australia, was done to identify the hurdles to treatment in the indigenous Aboriginal people, who have a high prevalence of HCV[23]. They interviewed 39 Aboriginal Australians in-depth and identified several specific challenges, including a lack of information provided at diagnosis, the stigma associated with HCV, and concerns about treatment's side effects and efficacy. Several groups have created healthcare policies to improve HCV screening and treatment, such as the Cherokee Nation Health Services in 2012. Through their collaborative efforts with the Center for Disease Control, HCV testing and treatment were significantly increased among Cherokee individuals[24]. Similar strategies have since been implemented by the Indian Health Services, resulting in HCV screening rate increases from 7.9% to 32.5%[25]. With targeted efforts and programs, identification and treatment of viral hepatitis can be possible in these vulnerable populations.

NON-ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE

Racial/ethnic disparities

The prevalence of NAFLD has continued to increase and now accounts for about 60% of all chronic liver disease, which surpasses all other etiologies. In fact, NASH is the leading cause of liver transplantation among Asians and Hispanics[26]. Much of the NAFLD is driven by the high prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nearly 2 billion people in the world are currently overweight, and by 2040, one billion people are expected to be living with obesity[27]. There was a strong association between NAFLD prevalence and national economic status[28]. European countries had a higher NAFLD prevalence (28.04%) than the Middle East (12.95%) and East Asia (19.24%). A systemic review and metaanalysis published in 2019 showed that roughly 16.7% of U.S. populations and 50% of the high-risk population had NAFLD[29]. In the United States, both the NAFLD prevalence and the risk for developing non-alcoholic steatohepatitis was the highest among Hispanics, followed by Whites, and the lowest in Blacks[29]. Underlying genetic factors may affect the progression of fatty liver disease. Hepatic steatosis within Hispanic communities may be partially attributable to the high rates of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and PNPLA3 polymorphism but this disparity in hepatic steatosis may be more evident in Hispanic communities of Mexican descent[30]. Asians have more central fat deposition at a lower body mass index (BMI) and have a higher prevalence of NAFLD with BMI < 25 kg/m2, compared to Western countries[31]. It is estimated that 8-19% of people with BMI < 25 kg/m2have NAFLD. Underlying genetic factors such as the PNPLA3 polymorphism may play a role in the development of lean NAFLD; 13%-19% of Asians have PNPLA3 rs738409 GG genotype, compared to 4% in White and 25% of Hispanics. It is also important to note that the high prevalence of HBV infections in Asian countries poses a risk for concurrent chronic HBV infection and NAFLD. Unfortunately, few studies have explored the problem of multiple contributing factors in the totality of a patient’s liver condition.

Gender disparities

While the predisposing factors for NAFLD have not been entirely elucidated, variations in sex hormones, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia may contribute to gender differences apparent in NAFLD. The prevalence of NAFLD is higher in men but increases steadily with age in women, especially after menopause, such that 31% of women over 60 years have NAFLD. A lower prevalence was noted in postmenopausal women on hormone replacement therapy[32]. While this suggests that estrogen may play a protective role in NAFLD, a longer duration of estrogen has been shown to increase the likelihood of NALFD development[33]. Women may also be at risk of faster liver fibrosis progression than men[34]. Furthermore, lower total testosterone level has been associated with severe NAFLD in men[35,36]. Differences in hyperlipidemia may also contribute to prognosis with NAFLD, and eventual outcomes as women with NAFLD were more likely to have a less atherogenic lipid profile and more favorable cardiovascular risk profile compared to males[37]. NASH is currently the leading cause of liver transplantation among females[26].

Disparities in access to care /difficulties in diagnosis

The shortage of hepatology providers may outpace the epidemic of patients with chronic liver disease, especially NAFLD. While primary care providers may be managing diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and obesity, there are no definitive guidelines on clinical management of NAFLD, so much of NAFLD is likely undiagnosed. A U.S.-based study showed that only 5.1% of patients with NAFLD were aware of their diagnosis[38]. Currently, universal screening for NAFLD is not recommended, but certain highrisk populations may benefit from screening for NAFLD; including metabolic syndrome, age older than 50-year-old, type 2 diabetes for more than 10 years, or obesity with BMI > 35 kg/m2[39]. Without definitive strategies for diagnosis and therapy, primary care providers may rely on their hepatology colleagues for assistance; however, referral patterns may vary by race, insurance, location, and availability of a tertiary referral center for liver disease. One study showed that only 17% of Blacks were referred to specialized care, compared to 92% of Hispanics and 97% of Whites[38]. Efforts are currently underway to develop more uniform guidelines to assist providers with NAFLD. Because patients with NAFLD have concurrent diabetes, cardiovascular disease and dyslipidemia, multidisciplinary care with various specialists is essential[40,41].

ALCOHOL-ASSOCIATED LIVER DISEASE

Three million deaths worldwide are due to harmful alcohol use, accounting for 5.3% of all deaths and 13.5% of deaths in people aged 20-39 years[42]. Alcohol intake and the sequelae of excessive consumption are complex problems that vary widely depending on socioeconomic, cultural, religious, geographic, and racial factors. Patterns of alcohol use can be related to a myriad of social problems, including racial discrimination, socioeconomic disadvantage, and interpersonal issues, and can be magnified by stressors and current events. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic necessitated social distancing and isolation, which markedly increased the rate of excessive alcohol use (binge drinking)[43]. One modeling study predicted this increase would ultimately affect long-term mortality and morbidity[44]. Disparities in alcohol-associated liver disease may also be related to the differences in any of these factors, and alcohol frequently exacerbates those with underlying chronic liver disease from any other etiology.

Racial disparities

Underlying genetic factors and cultural differences contribute to the behavior related to alcohol consumption and thus rates of alcohol-associated liver disease. For moderate alcohol intake, Blacks had increased mortality secondary to liver disease, but not Whites[45]. This study suggested that Black individuals were more susceptible to alcohol-associated liver injury. This observation may be due to underlying comorbidities and genetic polymorphisms. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black patients were more likely to be treated for alcoholic hepatitis, pancreatitis, and gastritis[43]. Providers’ racial bias may also influence treatment decisions for alcoholic liver disease. A recent United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) based study suggested that Black patients with alcohol-associated liver disease had less access to liver transplantation, but socioeconomic factors may have confounded this conclusion[46]. A population-based study from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System from 2007 to 2016 demonstrated that non-Hispanic Whites had the highest mortality rates for alcoholic liver disease; however, increases were seen in all Asian subgroups, with the highest increase in Japanese[5].

Gender disparities

Gender disparity for alcohol-associated liver disease can be attributed to differences in alcohol metabolism and perhaps social and cultural biases in women with heavy alcohol consumption. Men and women metabolize alcohol differently, as women typically have a higher serum alcohol level per drink[46]. Such factors may impact whether an individual seeks treatment and the severity of liver disease at presentation. For the treatment of alcohol use disorder, appropriate care provided by a mental health provider is often necessary, but only 10% of patients utilize this service. Women were less likely to seek specialist treatment for alcohol use disorder and to receive relapse prevention medications[47]. In recent years, there has been a rapid increase in the prevalence and mortality of women with alcohol-associated liver disease, especially alcoholic hepatitis[48]. This trend was more evident in Asian and Native American women. However, women with alcohol-associated liver disease were less likely to pursue liver transplant evaluation[46]. Among liver transplant recipients due to alcohol-associated liver disease, women had higher model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, higher rates of renal failure requiring dialysis, and higher rates of ventilator dependence before the transplant than men[49]. Men with alcohol-associated liver disease were more likely to be listed and receive liver transplantation than their female counterparts[50]. A history of other substance abuse was also more common in men, while women more often had an underlying psychiatric illness. Women were 9% less likely than men to experience long-term graft loss, though this gender disparity was isolated to patients with additional comorbidities.

Geographic disparities

Patterns of alcohol use may differ based on geography, and this may be related to restrictions on the purchase of alcohol, laws/prosecution of drivers under the influence of alcohol, and local advertising of alcoholic beverages. Many states have policies to regulate alcohol in the United States, though specific restrictions differ by state. Hadland et al[51] showed a strong correlation between state alcohol policies and the incidence and mortality of alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Mortality of alcohol-associated cirrhosis was highest among males in Western states and states with proportionally higher American Indians/Alaska Natives. A stricter alcohol policy was associated with lower mortality in females but not males. Among non-Indigenous descendants, more robust alcohol policy environments were linked to lower alcoholic cirrhosis mortality rates in both sexes.

AUTOIMMUNE LIVER DISEASE

Autoimmune liver disease includes autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). While the etiology of autoimmune liver is largely unclear, it is likely less to be related to behavioral or preventable causes. Disparities in autoimmune liver disease may be related to genetic factors, concurrent illnesses and socioeconomic issues that affect access to care. The current literature is predominantly based on White patients, and the data from racial minorities are limited[52]. Autoimmune liver disease often requires complex treatment provided by a hepatologist and often in coordination with a rheumatologist. Those with less access to specialists may experience inadequate or delayed care. In addition, racial minorities and recent immigrants may have issues with language barrier, which impacts health literacy and may result in resistance to treatment. Genetic polymorphism with the subtype of PNPLA3 in Hispanic patients with AIH predicted more severe liver disease and increased mortality after liver transplantation[53,54]. A single-center, retrospective casecontrol study evaluated the association between race/ethnicity and AIH[55]. After controlling age and sex, the odds of AIH were higher among Black, Latinos, or API compared to Whites. Though not quite statistically significant, Black patients trended to have higher ALT, IgG, INR, bilirubin, inflammation on biopsy, hospitalizations, and other concomitant autoimmune diseases. A small study suggested worse outcomes for Black and Asian patients with AIH[52]. A National inpatient sample-based study on PBC showed increased hospitalization rates in Hispanics and females[56]. Patients with PBC who were Black or had Medicaid have had significantly higher in-hospital mortality[57]. Black patients with PSC with inflammatory bowel disease reportedly had worse PSC-related survival outcomes and higher need for liver transplantation[52,58]. More studies are needed to clarify the impact of socioeconomic and racial disparities on each of these specific autoimmune liver diseases.

MALIGNANCY

HCC is the sixth most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. It frequently develops in patients with underlying liver diseases, such as those with cirrhosis, HCV, or HBV infections[59]. While appropriate surveillance can facilitate early detection HCC and improve survival, most cases are found at an advanced stage. There are significant differences in the incidence of HCC by race, but this may be likely be related to differences in the underlying chronic liver disease that predisposed a patient to HCC.

Gender disparities

HCC occurs two to four times higher in men compared to women[18,60]. Some of this is likely due to the differences in viral hepatitis between genders and behavioral risk factors which may have led to viral hepatitis. In addition, differences in comorbidities such as alcohol use, smoking, and obesity may contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis and outcome. In the United States, increased mortality rates for HCC from 2000 to 2015 were seen in less educated patients, particularly men[61]. In contrast, women had significantly lower mortality from HCC[62], possibly due to early detection and response to the first treatment10]. Studies have also suggested that estrogen may have protective role in HCC development through reduction of interleukin-6 mediated hepatic inflammatory responses[60].

Racial disparities

While the etiology of liver disease is an essential factor affecting incidence and survival in HCC, previous U.S. studies have shown that age-adjusted HCC incidence was highest in APIs, followed by Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites[63,64]. Among Asian ethnic groups, the highest HCC incidence rates were observed among Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians. Southeast Asians were twice as likely to have HCC as other Asians and an 8-fold risk compared to Whites. While Asian countries have a considerably higher burden of disease, there are subgroups within these countries that demonstrate differences in HCC. A study from China, showed differences in mortality between Mongols vs Non-Mongols, primarily attributed to the difference in underlying HBV infections[65]. For other races, Black patients had a lower survival overall from HCC than their White or Hispanic counterparts[66]. Black patients typically present with advanced stages of HCC at the time of diagnosis and are thus less likely to receive curative treatment[66,67]. Even after adjusting for stages, Blacks and Hispanics were less likely to receive curative treatment for HCC and lower healthcare utilization for HCC. Blacks had a higher risk of inpatient mortality[68]. On the other hand, Asians are more likely to have underlying HBV infection without underlying cirrhosis; therefore, they are more likely to undergo curative resection[66].

Socioeconomic status

The role of socioeconomic status has been evaluated for disparities in HCC outcomes. A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database study showed that patients who reside in the area with a higher cost of living index was associated with stage I disease, smaller tumor size, and increased likelihood of surgical intervention or loco-regional therapy[69]. Earlier detection of HCC in wealthier patients may infer more effective surveillance in this population. Similar findings were found in a study based on the Korean National Health Insurance sampling cohort[70]. This study of 7325 patients showed a decreased 5-year mortality for HCC among lower-income patients and middle-aged men. HCC outcomes also vary by hospital. Safety-net hospitals in the U.S. provide much of the care for patients with lower household income, education levels, and racial minorities. HCC patients in these safety-net hospital were less likely to undergo liver resection or transplantation and had higher procedure-specific mortality[71]. Insurance and employment status may also affect specialist referral and outcome. In a study conducted in China, Wu et al[72] showed increased mortality from HCC in patients with a basic health insurance compared to those with an employment-based insurance. Unemployment may also be a factor in HCC development and care. A U.S. census and National Health Interview survey based study showed that there was that alcohol use disorder and viral hepatitis was nearly 40% higher among the unemployed, and HCC mortality was worse in the unemployed group[73].

Geographic disparities

Place of residence may also affect the incidence and survival in HCC. A U.S. based SEER database study based on 83638 patients showed that rural and suburban residents had higher HCC mortality and were less likely to receive treatment than urban residents[74]. Insurance status itself may not guarantee appropriate access to healthcare providers as patients are unable to pay for associated costs in travelling to tertiary referral centers. Lee et al[75] showed in the SEER database and CDC’s cancer registries that there was a state-level racial and ethnic disparity in the incidence of HCC. This incidence trends had some correlation with obesity rates of the states. Geographic disparities were also identified in a study from Australia, where HCC incidence was highest amongst those residing in metropolitan cities and remote areas with high Indigenous populations[76].

Disparities in surveillance for HCC

While primary care providers are very familiar with screening for common cancers like breast and colon, many are not aware of current surveillance guidelines for HCC. As such, access to hepatologist or gastroenterologist may improve the rate of appropriate HCC surveillance. Current AASLD guidelines for HCC surveillance recommend ultrasound every 6 mo with or without alpha feto-protein, in patients with cirrhosis, chronic HBV, and chronic HCV with greater than stage 3 fibrosis[59]. Therefore, an appropriate surveillance for HCC requires recognition of the underlying chronic liver disease, appropriate testing and then referral for contrast-enhanced imaging for suspicious lesions. Without recognition of the underlying chronic liver disease and indications, surveillance cannot occur. As mentioned previously, many patients in the U.S. have unrecognized viral hepatitis and will neither receive antiviral agents nor undergo surveillance[9,12,77]. Despite guidelines, only 17% of HCC are detected in early stages (BCLC 0 and A) in the U.S., while European countries was 10%-30%[78]. On the other hand, Japan implemented nationwide HCC surveillance in 1980’s with free testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and HCV Ab in the clinics and meticulous surveillance. This eventually led to earlystage detection of HCC in 60%-65% of patients. Factors such as race, obesity, ascites, operator’s experience may also affect the early detection rates of HCC[12,79,80]. Finally, there is likely a complex interplay between these factors, socioeconomics and access to care that all affect surveillance and early detection in HCC.

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Liver transplantation is considered the definitive treatment for end stage liver disease and early-stage HCC that is not amenable to resection. Because this is a risky operation, an expensive endeavor and a limited resource, it is not unexpected that disparities would be evident. Patients must be medically suitable with no active non-HCC malignancy, no ongoing infection, and adequate cardiovascular function. In addition, patients must be medically compliant, without active substance abuse and have financial stability/medical insurance coverage to ensure adequate access to immunosuppressive medications post-transplant. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic influenced liver transplant access among the minority population. A UNOS-based study showed minority had a more significant reduction in transplant (Minority: 15% vs White: 7% reduction) and listing for transplant (14% vs 12% reduction, respectively), despite a higher median MELD score (23 vs 20, respectively) during early COVID-19 period[81]. The reduction in transplants became more prominent for patients with public insurance than private insurance. Another study from Mexico showed an unequal reduction of liver transplantation for public (88% reduction) and private (35% reduction) hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic[82].

Gender disparity

In the United States, the MELD-Na score is the current organ allocation method for liver transplantation. This score is predictive of mortality on the waiting list but can create disparities. Gender disparities can occur because differences in muscle mass in males vs females affects creatinine, which is a variable in MELD. The current allocation system does not account for these sex differences in creatinine and anthropometric measure. In fact, Locke et al[83] showed that women had higher waitlist mortality and less likelihood of receiving deceased donor liver transplantation. Another cohort study by Cullaro et al[84] showed that women were 10% more likely to be removed from the waitlist for being too sick for liver transplantation. One study found that women removed from the list were older, had non-HCV liver disease, and had higher rates of hepatic encephalopathy. Another cohort study on liver transplantation for NASH showed that women were less likely to be White and listed with MELD exception points[85]. In multivariable analysis, women with NASH were 19% less likely to receive liver transplantation compared to men with NASH through the follow-up period even after adjusting for multiple other factors. Overall, women were less likely to have liver transplantation while more likely to die without transplant, be removed from the waiting list due to clinical deterioration or remain on the waiting list without liver transplantation. In order to decrease gender disparities in liver transplantation, Kim et al[86] attempted to address sexual disparity by creating an updated MELD 3.0, incorporating sex difference, which may provide a better mortality prediction. Efforts are currently underway to implement this in the U.S. Another study from Toronto, Canada, highlighted that there is a broader availability of living donor liver transplants (LDLT) to women, which may provide a protective factor to minimize the gender disparity[87].

Racial disparity

Racial disparities in transplant can be seen in wait list mortality, use of simultaneous liver-kidney transplant (SLK), LDLT and eventual outcomes. A study on the UNOS liver transplant registry showed lower waitlist mortality among Asian compared to White after correcting for the MELD score[88]. Black patients tended to have higher MELD scores at the time of listing for liver transplantation but similar rates of waitlist mortality after correcting for MELD scores. Patients with end stage liver disease often have comorbid renal dysfunction, and SLK is considered. However, Black and Hispanic patients with renal dysfunction who are listed for liver transplantation were more likely to undergo SLK than White[89]. LDLT was noticeably lower among Hispanic, Black, and Asian patients compared to White patients. Blacks in particular, were less likely to inquire about LDLT during the evaluation process[90].

Finally, there are disparities in outcome and survival after liver transplantation. Differences in outcome after transplant may be biologically driven and may also be related to medical compliance. Blacks and women with HBV had worse long-term outcomes post-transplant compared to other races[91]. Recurrence of HBV was significant for Blacks even ten years post liver transplant, affecting the survival rate. While there have been racial disparities to liver transplantation in the past, the U.S. continues to develop broader sharing policies and allocation schemes which have helped equalize access to liver transplantation for all populations[92]. Longer term coverage of immunosuppression by Medicare and other insurances will also help improve long-term outcomes after liver transplant.

CONCLUSION

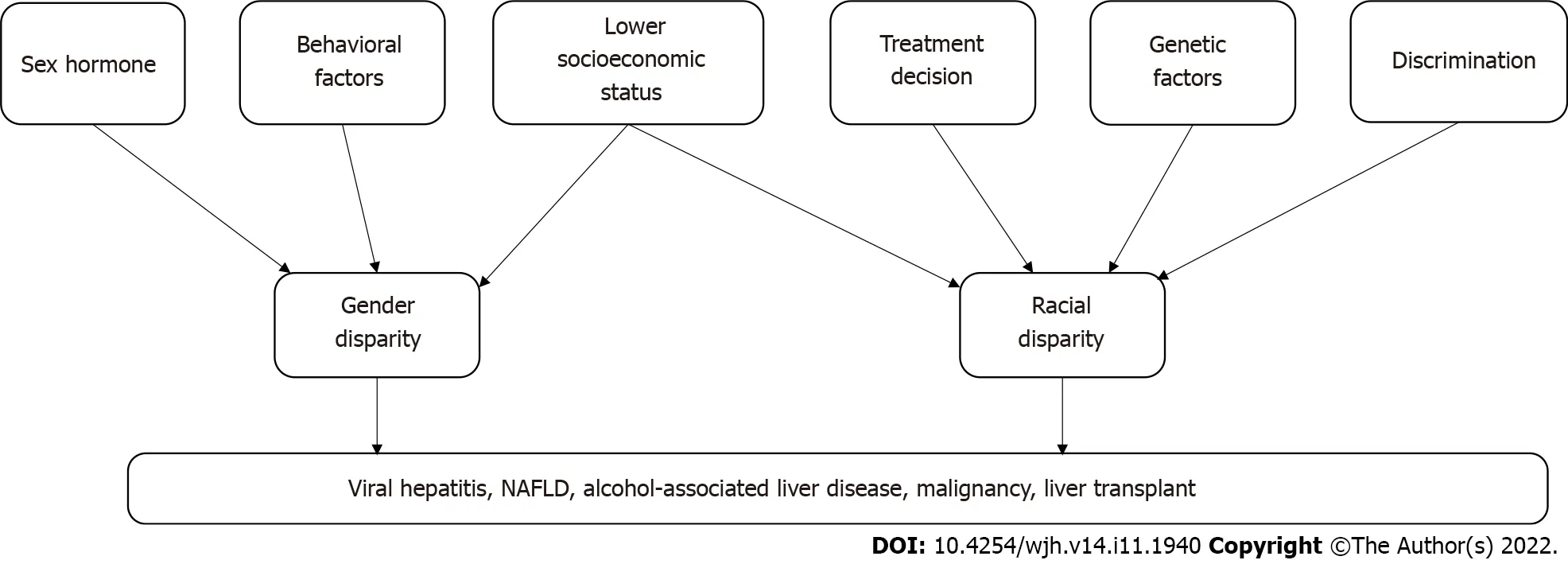

Disparities in liver disease and treatment are frequent and may be related to gender, race, geography, socioeconomic status and specific behaviors that predispose to liver disease (Figure 1). The need for complex management of these diseases, limited resources of liver transplantation and the inadequate number of specialists to care for these patients is further magnifying these disparities. Future studies should focus on evaluation of a language barrier among immigrant in regard to disparity and interventions to address these disparities.

Figure 1 Summary of liver disease disparity. NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A literature review was provided by Danielle Westmark, MLIS, IPI PMC, and Cindy Schmidt, M.D., M.L.S., from the Leon S. McGoogan Health Sciences Library at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions: Sempokuya T, Warner J, Azawi M, Nogimura A contributed to the literature review, manuscript drafting, and editing; Wong LL contributed to study supervision, manuscript drafting, and editing; all of the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Wong LL is a speaker bureau for Eisai. All other authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin: United States

ORCID number: Tomoki Sempokuya 0000-0002-7334-3528; Josh Warner 0000-0002-0208-0492; Muaataz Azawi 0000-0003-0700-9641; Akane Nogimura 0000-0001-5696-9900; Linda L Wong 0000-0003-3143-5384.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases;American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

S-Editor: Wang JL

L-Editor: A

P-Editor: Wang JL

World Journal of Hepatology2022年11期

World Journal of Hepatology2022年11期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Multiple hepatic infarctions secondary to diabetic ketoacidosis: Acase report

- Elevated calprotectin levels are associated with mortality in patients with acute decompensation of liver cirrhosis

- Liver test abnormalities in asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients and their association with viral shedding time

- Haemochromatosis revisited

- Current management of liver diseases and the role of multidisciplinary approach