Hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensation, and mortality based on hepatitis C treatment: A prospective cohort study

Gwang Hyeon Choi,Eun Sun Jang, Young Seok Kim, Youn Jae Lee, In Hee Kim, Sung Bum Cho Han Chu Lee, Jeong Won Jang,Moran Ki, Hwa Young Choi, Dahye Baik, Sook-Hyang Jeong

Abstract

Key Words: Hepatitis C virus; Direct-acting antiviral; Sustained virologic response; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Mortality

lNTRODUCTlON

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liverrelated and overall mortality. In 2019, the World Health Organization estimated that 58 million people worldwide had chronic HCV infection[1]. Currently, this substantial public health burden can be reduced by active screening and treatment with highly tolerable direct-acting antivirals (DAA), which result in a cure rate of more than 95% in terms of the sustained virologic response (SVR)[2-4].

From the identification of HCV to the introduction of DAA therapy, interferon (IFN)-based therapy(IBT) was the only option for HCV treatment, with an approximate SVR rate of 50%[5]. Although IBTinduced SVR includes a wide variety of adverse effects and narrow indications, it significantly reduces the incidence of HCC and long-term mortality[6,7]. Furthermore, DAA-induced SVR has resulted in reductions in hepatic fibrosis[8,9], portal hypertension[10], hepatic decompensation[11], HCC incidence[11,12], and liver-related and overall mortality[11,13]; however, the follow-up durations were relatively short.

To reach the HCV elimination goal of 2030, it is imperative to understand the regional epidemiology and outcomes of HCV. However, prospective studies of the long-term outcomes after treatment with IBT or DAA are limited in many Asian countries, where hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the major cause of liver-related complications. Additionally, comparative studies of the outcomes of SVR induced by IBT and DAA are scarce.

We established a prospective, nationwide, multicenter HCV cohort (the Korea HCV cohort study)funded by the Korean National Institute of Health in 2007. Using these data, we aimed to elucidate the clinical outcomes, including HCC, hepatic decompensation, and all-cause death, among Korean patients with chronic HCV infection. We compared the outcomes based on the antiviral treatments (untreated,IBT, and DAA) and analyzed patients after achieving SVR (IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups).Additionally, we investigated outcome-determining factors after SVR.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

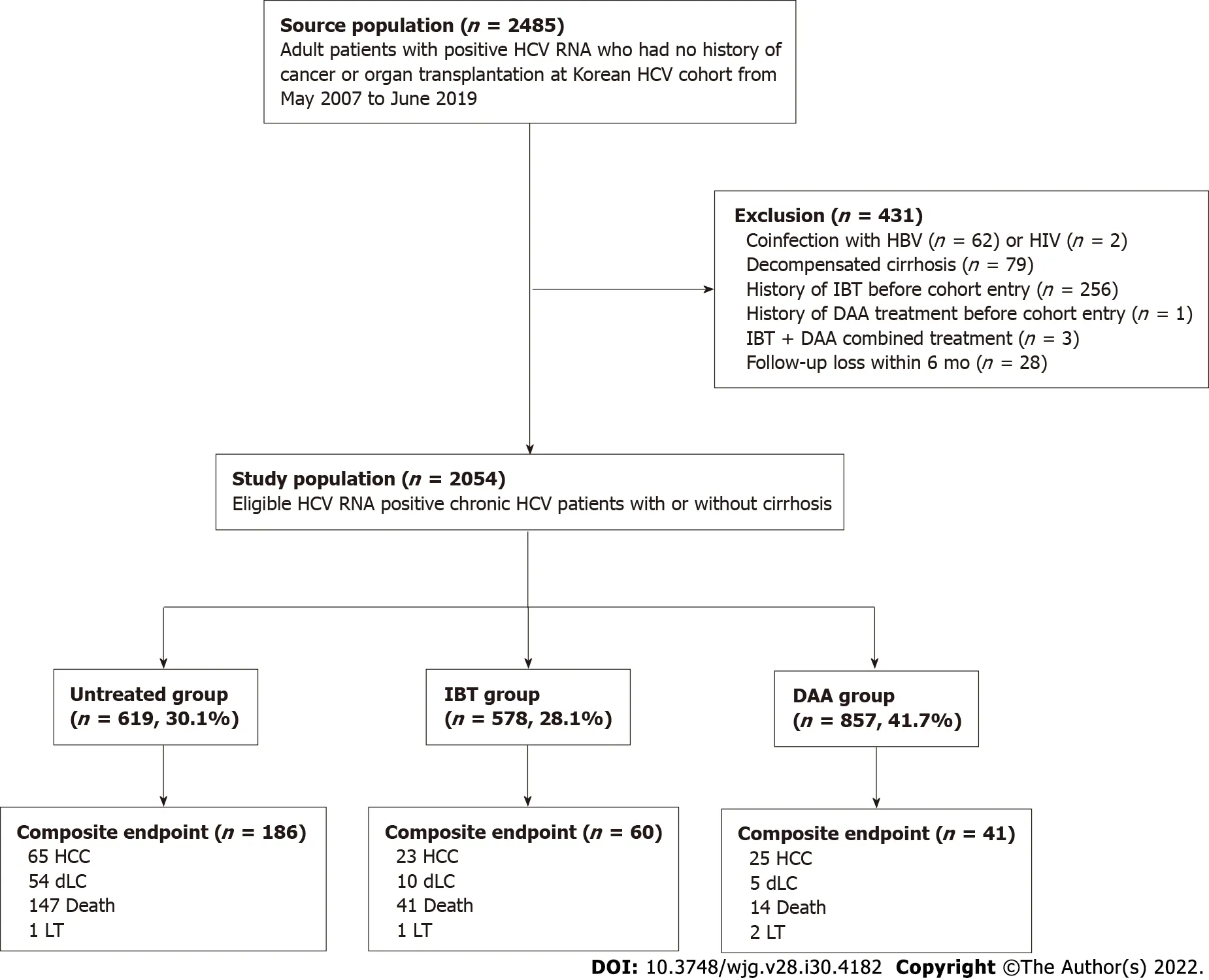

The Korea HCV cohort is a prospective cohort of 2485 adult patients with HCV RNA positivity at seven tertiary centers nationwide enrolled from January 2007 to June 2019 in South Korea. Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded: Positive serology for HBV surface antigen (n= 62) or HIV (n= 2); decompensated cirrhosis at enrollment (n= 79); previous antiviral treatment before cohort entry (n= 260); and less than 6 mo of follow-up (n= 28). Additionally, patients who had HCC before or at the time of cohort entry were excluded.

Therefore, 2054 viremic patients with or without compensated cirrhosis were analyzed as the entire cohort, which was further classified into three groups based on their treatment: untreated group (n=619; 30.2%); IBT group (n= 578; 28.1%); and DAA group (n= 857; 41.7%). Patients in the untreated group did not receive IBT or DAA treatment during the entire follow-up period. Subject selection, classification, and overall outcomes are summarized in Figure 1.

In the entire cohort, 1267 patients achieved SVR (61.7%) with IBT (n= 451) or DAA (n= 816); these patients comprised the SVR cohort. Diagnostic criteria for liver cirrhosis were based on histology or at least one clinical sign of portal hypertension, such as cirrhotic features on radiological images, platelet count less than 100,000/mm3, and documented gastroesophageal varices without hemorrhage. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of seven hospitals, and each enrolled patient provided written informed consent.

Data collection at baseline and follow-up visits

At the time of enrollment, trained research coordinators at the seven hospitals interviewed the patients using a standardized questionnaire that included demographic and socioeconomic factors (age, sex,body mass index, education level, and occupation), health behaviors (smoking and alcohol consumption), comorbidities (extrahepatic cancers, thyroid disease, psychiatric disease, diabetes, kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease), and lifetime exposure to risk factors for HCV infection.

Laboratory data at baseline and follow-up visits were collected from the medical records, including the anti-HCV antibody, serum HCV RNA level, HCV genotype, HBV surface antigen, HBV core antibody immunoglobulin G (anti-HBc IgG), white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count,aspartate aminotransferasel (AST), alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin,albumin, creatinine, prothrombin time (PT) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). The following three noninvasive serum fibrosis assessment scores were calculated at the index date: The fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index[14], the AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) score[15], and the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score[16].

The results of imaging studies, such as abdominal ultrasonography or computed tomography, liver pathology, and transient elastography (FibroScan?, Echosens, Paris, France), were collected when available. Detailed information about antiviral treatment, including therapeutic regimens, duration, and achievement of SVR, was collected from the patients’ medical records. These data were entered into the established electronic case report form on the authorized website of the Korean Centers for Disease Control Korea HCV cohort study (http://is.cdc.go.kr/) by the research coordinators. All input data were quality-controlled by independent statistical researchers (Baik D, Choi HY, and Ki M) at least four times per year.

Follow-up evaluations

Figure 1 Patient flow diagram. DAA: Direct-acting antivirals; dLC: Decompensated liver cirrhosis; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV:Hepatitis C virus; IBT: Interferon-based treatment; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; LT: Liver transplantation.

All patients underwent regular clinical assessments every 3 to 12 mo, and HCV treatment was recommended by their attending physicians according to the treatment guidelines for HCV infection unless there were contraindications or patient's refusal. If the patients were treated, then SVR was evaluated, and regular follow-up visits every 6 to 12 mo after SVR were encouraged. HCC surveillance using abdominal ultrasonography and serum AFP tests every 6 to 12 mo were recommended according to the pretreatment fibrosis stage. If the patients did not adhere to the regular follow-up schedule, then research coordinators called the patients or their families to encourage them to attend the clinic and to check their survival status, disease progression to hepatic decompensation, or development of HCC.The end of follow-up was defined as the date of death/liver transplantation (LT), or the last follow-up date (June 30, 2020).

Measurement of liver-related outcomes

Outcomes included the incidences of HCC, hepatic decompensation, and death/LT. HCC was diagnosed according to pathology or typical imaging criteria observed on dynamic computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging in accordance with the Korean Liver Cancer Study Group guidelines (similar to major international guidelines)[17]. Decompensated liver cirrhosis was defined as the presence of ascites, jaundice, variceal bleeding, encephalopathy, or a combination of these[18]. All-cause mortality or death/LT was directly documented or indirectly indicated as disqualification from the National Health Insurance status provided in the electronic medical records. In Korea,enrollment in the National Health Insurance is compulsory for all individuals; therefore, disqualification from the National Health Insurance indicates death or emigration in most cases[19]. To verify the survival status, physician-confirmed death certificate data, including the date and cause of death, were obtained from the Statistics Korea mortality database, which was established in 1981.

To calculate the outcomes of the entire cohort, the index date of the entire cohort was defined as the date of cohort entry when HCV RNA positivity was confirmed by the referred clinics. To compare the outcomes of patients with SVR induced by IBT and patients with SVR induced by DAA, the index date for the SVR cohort was defined as the initiation day of the antiviral treatment. SVR was evaluated using an intention-to-treat analysis; therefore, patients who received at least one dose of IBT or DAA were included.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the patients were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables,and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) ort-test was used for continuous variables. For multiple comparisons, a one-way ANOVA was used followed by a Bonferroni correction. The total follow-up (in person-years) of each group was calculated by multiplying the cohort population size by the average follow-up in years. Survival time was calculated as the time from cohort entry (the entire cohort) or the start of the first treatment (SVR cohort) until the date of death/LT or the last available follow-up date. A few patients who received a second course of DAA treatment because of failure of the first DAA treatment were censored at the time of retreatment.

The incidences and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the outcomes for each group based on treatment were calculated using an exact method based on the Poisson distribution. Cumulative incidence curves for outcome development were estimated using the pseudo-Kaplan-Meier method with a clock reset procedure for patients treated with IBT or DAA during follow-up and compared using the log-rank test.Therefore, patients who had received IBT and subsequent DAA treatment were considered as the DAA group, but the period between IBT and DAA treatment was included in the IBT group with no event.

A time-varying Cox regression model was used to determine the factors associated with outcomes,and the adjusted hazard ratio was estimated for the entire cohort and the SVR cohort. In the models,baseline variables (sex, body mass index, alcohol, smoking, HCV genotype) were adjusted, and age,antiviral treatment, laboratory data, achievement of SVR, and presence of cirrhosis were considered time-dependent variables. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with HCC or death/LT, and the adjusted hazard ratio was estimated for the SVR cohort at the time of IBT or DAA initiation. Covariates withP< 0.05 in the univariate Cox regression model were used as covariates for the multivariate Cox regression analyses. To confirm the multivariate analysis results for the SVR cohort, significant differences in characteristics at the time of initiation of each treatment were adjusted by propensity score (PS) matching for all possible variables, including the time from cohort entry to treatment. We used nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper size of 0.1 and matched the patients using a 1:1 ratio. The covariate balance was considered to be achieved if the absolute standardized difference between the two groups was ≤ 0.1.

AllP-values were two-sided, andP< 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS (version 21; IBC Corp.,Armonk, NY, United States) and R (version 4.0.4; http://cran.r-project.org/) software were used for statistical analyses. The R package ofMatchItwas used for matching analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the entire cohort

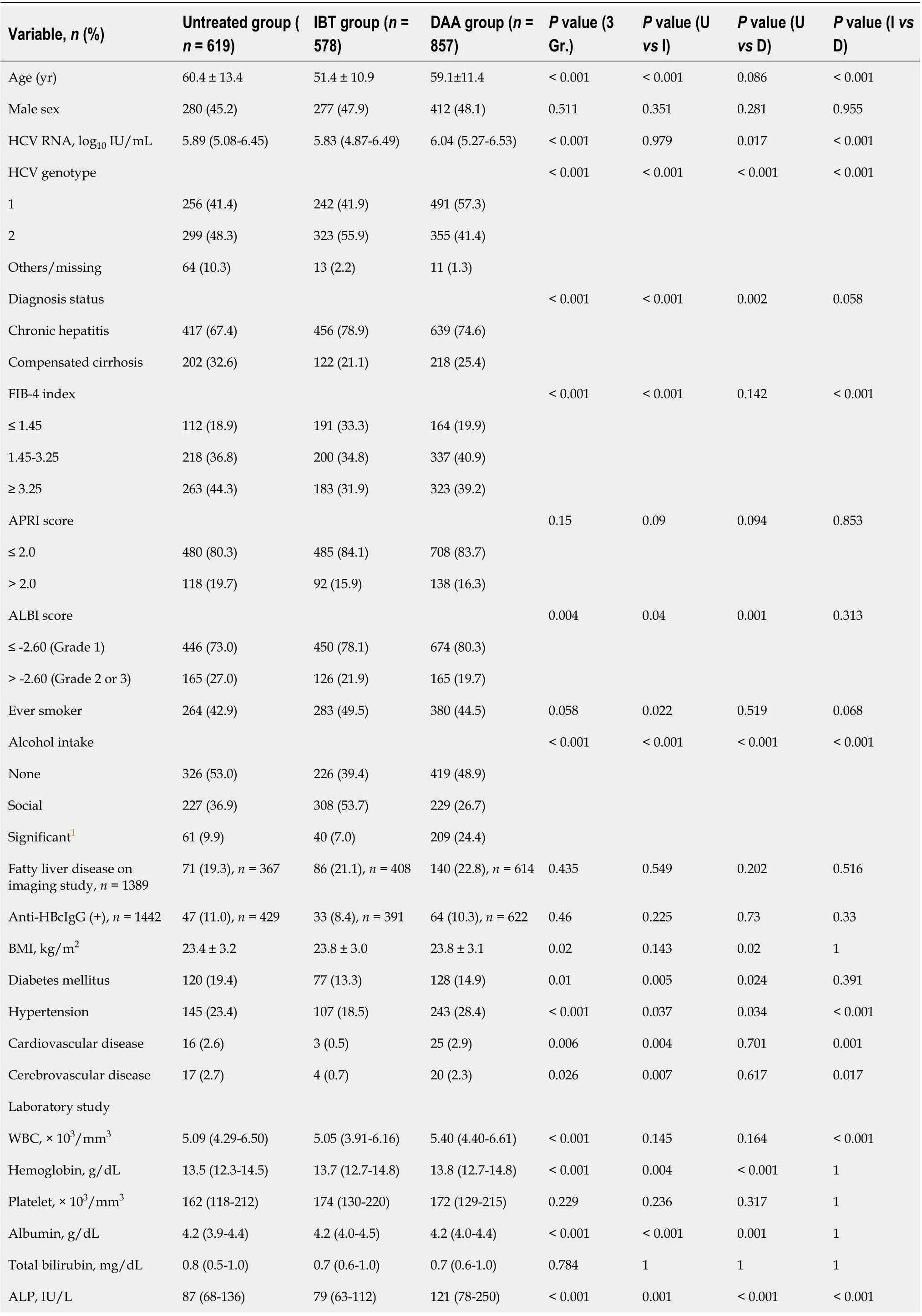

The demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the entire cohort (n= 2054), untreated group(n= 619; 30.1%), IBT group (n= 578; 28.1%), and DAA group (n= 857; 41.7%) at the index date are provided in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 57 years; 46.5% were men and 27.4% had compensated cirrhosis.

Compared with the untreated and DAA groups, the IBT group was significantly younger, had a higher proportion of genotype 2, lower rates of alcohol consumption, cirrhosis and high FIB-4 index values (≥ 3.25), and fewer comorbidities.

Among the DAA group, 14.0% had been treated with an IFN-based regimen after cohort enrollment,and 86.0% were treatment-naive. DAA treatments administered were sofosbuvir plus ribavirin (32.1%),daclatasvir plus asunaprevir (26.3%), elbasvir plus grazoprevir (13.7%), glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir(13.7%), ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir (9.1%), and ombitasvir plus paritaprevir plus ritonavir plus dasabuvir (3.9%).

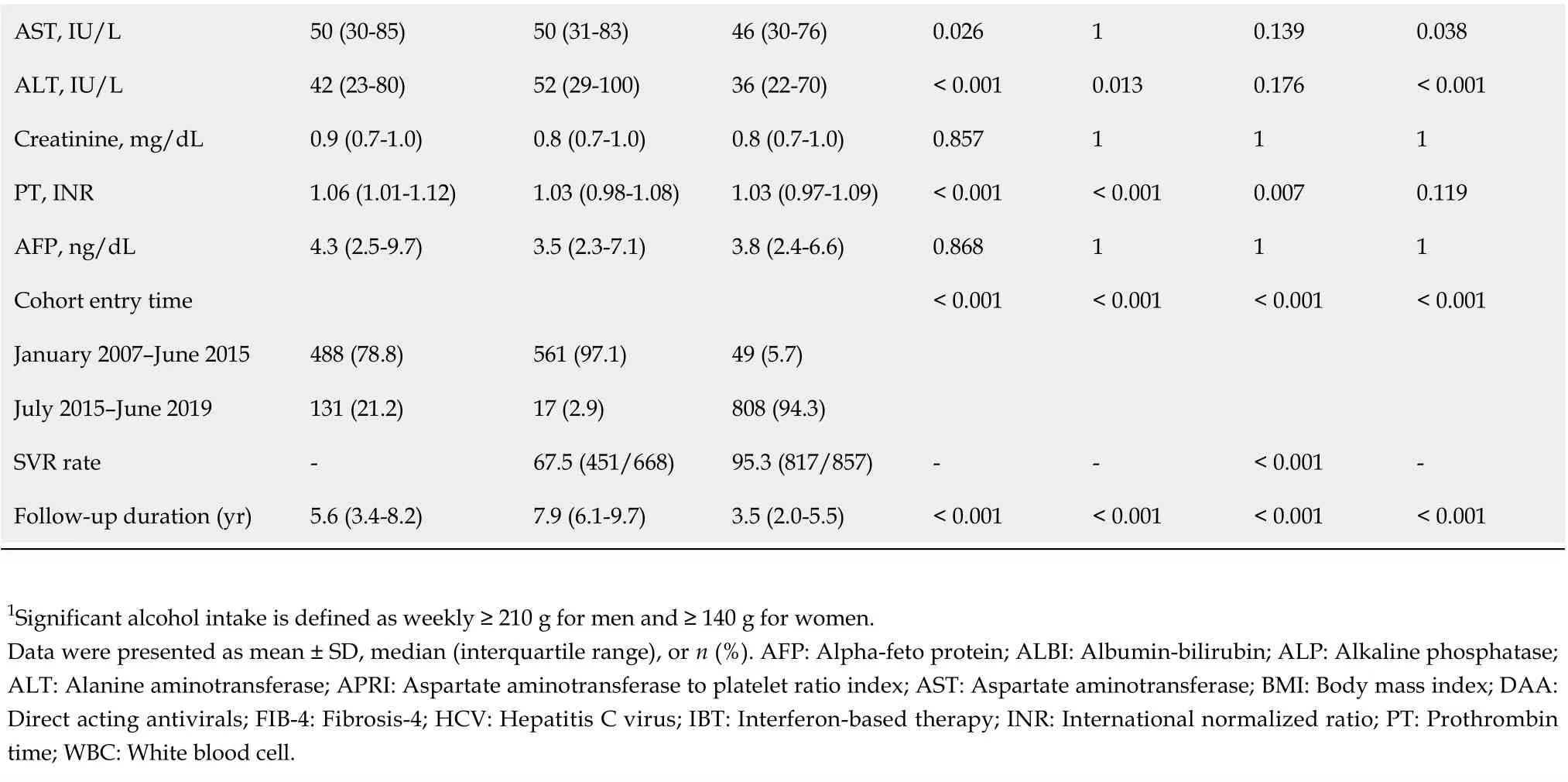

Incidences of HCC, decompensation, and death/LT in the entire cohort according to treatment, SVR,or the presence of liver cirrhosis

The median time periods between cohort entry (index date) and the end of follow-up were 5.6 years[interquartile range (IQR), 3.4-8.2] for the untreated group, 7.9 years (IQR, 6.1-9.7) for the IBT group, and 3.5 years (IQR, 2.0-5.5) for the DAA group (Table 1). During this period, 113 patients developed HCC, 69 patients experienced hepatic decompensation, 202 patients died (119 Liver related and 83 non-liver related), and four patients underwent LT.

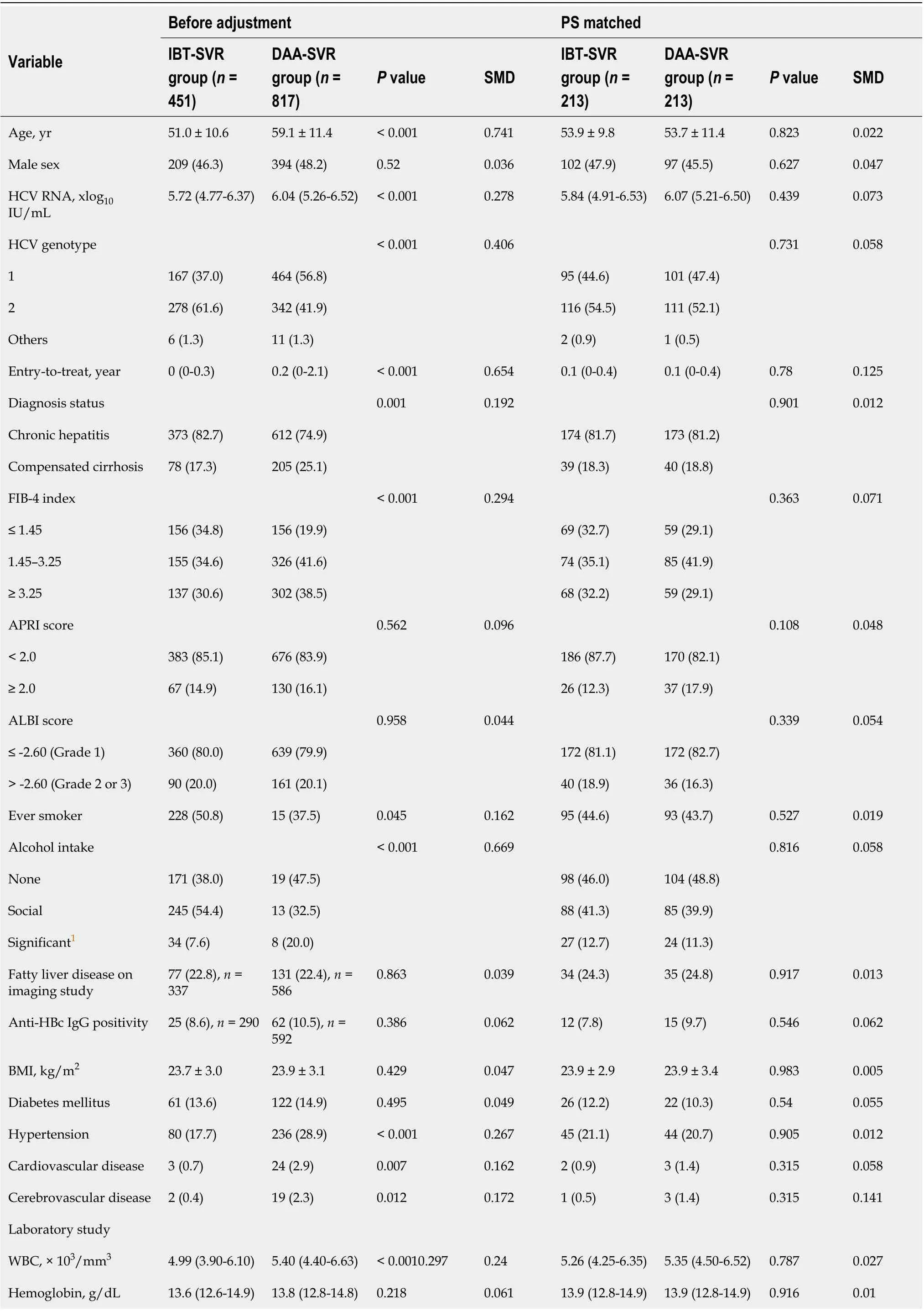

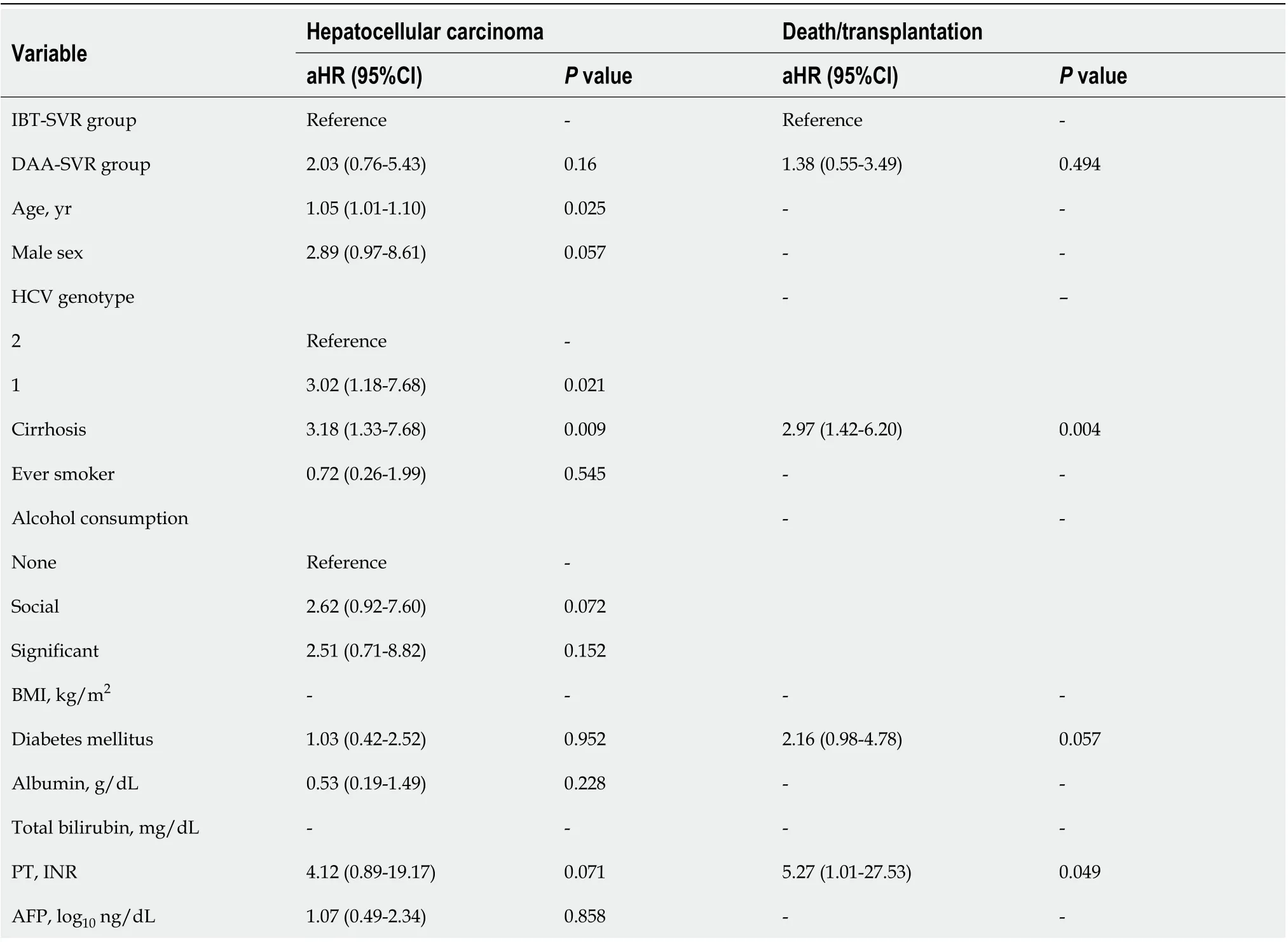

As shown in Table 2, the estimated HCC incidence rates per 100 person-years for the untreated group, IBT group, and DAA group were 1.98 (95%CI: 1.56-2.52), 0.59 (95%CI: 0.39-0.89), and 1.16(95%CI: 0.78-1.71), respectively (Table 2). The incidence rates of hepatic decompensation per 100 personyears for the untreated group, IBT group, and DAA group were 1.62 (95%CI: 1.24-2.11), 0.25 (95%CI:0.14-0.47), and 0.23 (95%CI: 0.10-0.55), respectively. The incidence rates of death/LT per 100 personyears for the untreated group, IBT group, and DAA group were 3.33 (95%CI: 2.85-3.91), 0.87 (95%CI:0.64-1.18), and 0.65 (95%CI: 0.40-1.06), respectively. The incidence rates of all three outcomes were significantly lower in the IBT and DAA groups compared with the untreated group. However, theincidence of HCC in the non-cirrhotic group was not significantly different between the untreated and DAA groups, while the incidences of decompensation and death/LT were significantly lower in the DAA group compared with the untreated group. The cumulative outcome incidences for the untreated,IBT, and DAA groups are shown in Figure 2, and those for the non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic subgroups are shown in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the entire hepatitis C virus cohort according to the treatment

AST, IU/L 50 (30-85)50 (31-83)46 (30-76)0.02610.1390.038 ALT, IU/L 42 (23-80)52 (29-100)36 (22-70)< 0.0010.0130.176< 0.001 Creatinine, mg/dL 0.9 (0.7-1.0)0.8 (0.7-1.0)0.8 (0.7-1.0)0.857111 PT, INR 1.06 (1.01-1.12)1.03 (0.98-1.08)1.03 (0.97-1.09)< 0.001< 0.0010.0070.119 AFP, ng/dL 4.3 (2.5-9.7)3.5 (2.3-7.1)3.8 (2.4-6.6)0.868111 Cohort entry time < 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001 January 2007-June 2015488 (78.8)561 (97.1)49 (5.7)July 2015-June 2019131 (21.2)17 (2.9)808 (94.3)SVR rate -67.5 (451/668)95.3 (817/857)--< 0.001-Follow-up duration (yr)5.6 (3.4-8.2)7.9 (6.1-9.7)3.5 (2.0-5.5)< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001 1Significant alcohol intake is defined as weekly ≥ 210 g for men and ≥ 140 g for women.Data were presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or n (%). AFP: Alpha-feto protein; ALBI: Albumin-bilirubin; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase;ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: Body mass index; DAA:Direct acting antivirals; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IBT: Interferon-based therapy; INR: International normalized ratio; PT: Prothrombin time; WBC: White blood cell.

Multivariable analyses of factors associated with HCC, decompensation, and death/LT in the entire cohort

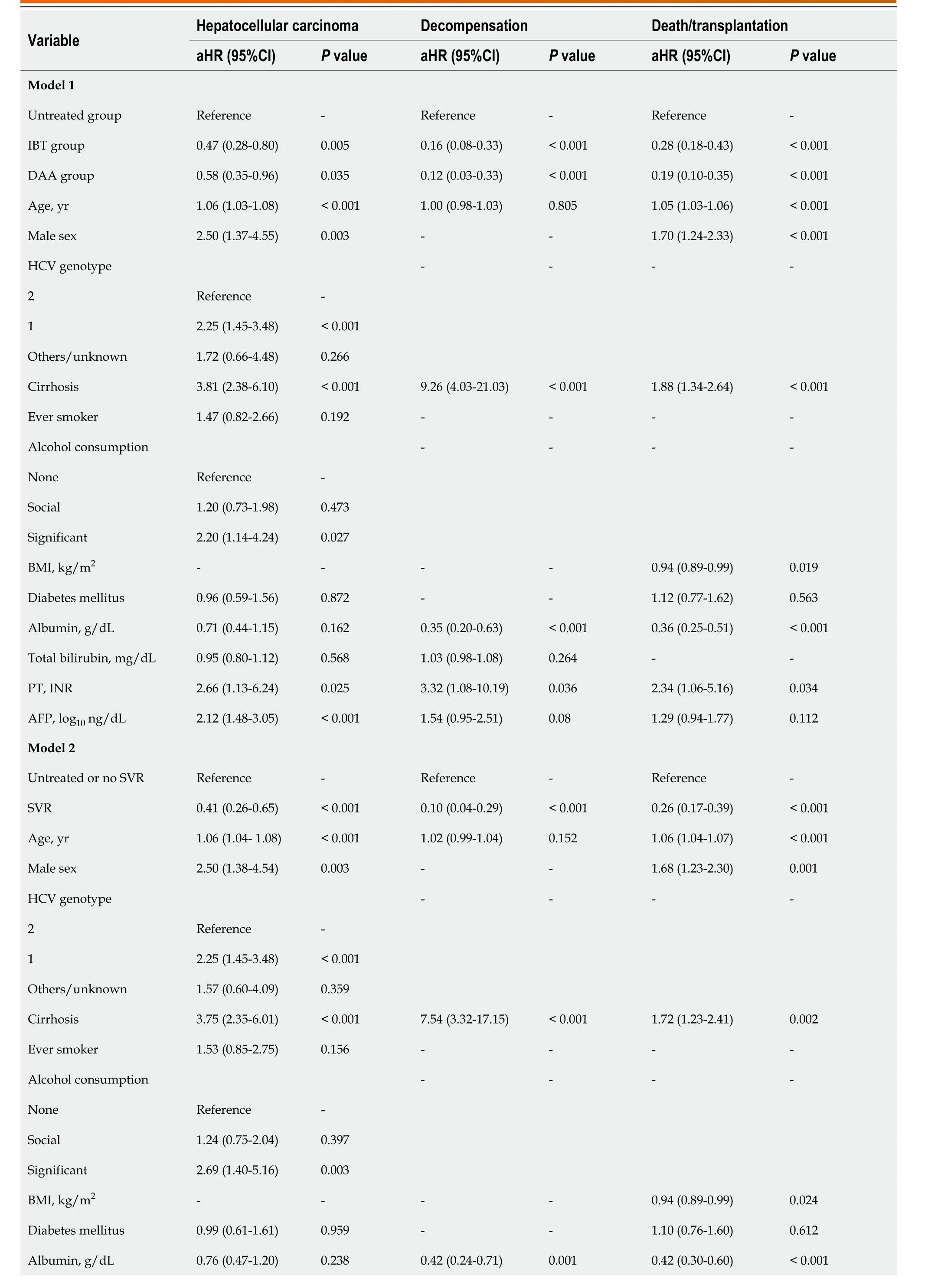

A multivariable time-varying Cox regression analysis with the untreated group as a reference showed that IBT [hazard ratio (HR), 0.47; 95%CI: 0.28-0.80;P= 0.005] and DAA groups (HR, 0.58; 95%CI: 0.35-0.96;P= 0.035) were independently associated with a significantly lower risk of HCC (Table 3, model 1).Other independent HCC risk factors were older age (HR, 1.06; 95%CI: 1.03-1.08;P< 0.001), male sex(HR, 2.50; 95%CI: 1.37-4.55;P= 0.003), genotype 1 (HR, 2.25; 95%CI: 1.45-3.48;P< 0.001), the presence of cirrhosis (HR, 3.81; 95%CI: 2.38-6.10;P< 0.001), significant alcohol consumption (HR, 2.20; 95%CI: 1.14-4.24;P= 0.027), prolonged PT (HR, 2.66; 95%CI: 1.13-6.24;P= 0.025), and higher AFP level (HR, 2.12;95%CI: 1.48-3.05;P< 0.001) (Table 3, model 1).

The death/LT incidence decreased independently after antiviral treatment with IBT (HR, 0.28; 95%CI:0.19-0.43;P< 0.001) or DAA (HR, 0.19; 95%CI: 0.10-0.35;P< 0.001) (Table 3, model 1). In contrast, older age (HR, 1.05; 95%CI: 1.03-1.06;P< 0.001), male sex (HR, 1.70; 95%CI: 1.24-2.33;P< 0.001), the presence of cirrhosis (HR, 1.88; 95%CI: 1.34-2.64;P< 0.001), lower body mass index (HR, 0.94; 95%CI: 0.89-0.99;P= 0.019), lower albumin level (HR, 0.35; 95%CI: 0.25-0.51;P< 0.001), and prolonged PT (HR, 2.34; 95%CI:1.06-5.16;P= 0.034) independently increased mortality/LT rates. Antiviral treatment, cirrhosis, albumin level, and PT were independently associated with the risk of decompensation (Table 3, model 1).

We established another multivariable model (model 2) by replacing the achievement of SVR instead of IBT or DAA treatment. A multivariate time-varying Cox regression analysis of the combined outcomes of the untreated and no SVR groups as a reference showed that SVR induced by either IBT or DAA significantly decreased the risk of HCC (HR, 0.41; 95%CI: 0.26-0.65;P< 0.001), decompensation(HR, 0.10; 95%CI: 0.04-0.29;P< 0.001), and death/LT (HR, 0.26; 95%CI: 0.17-0.39;P< 0.001) (Table 3,model 2).

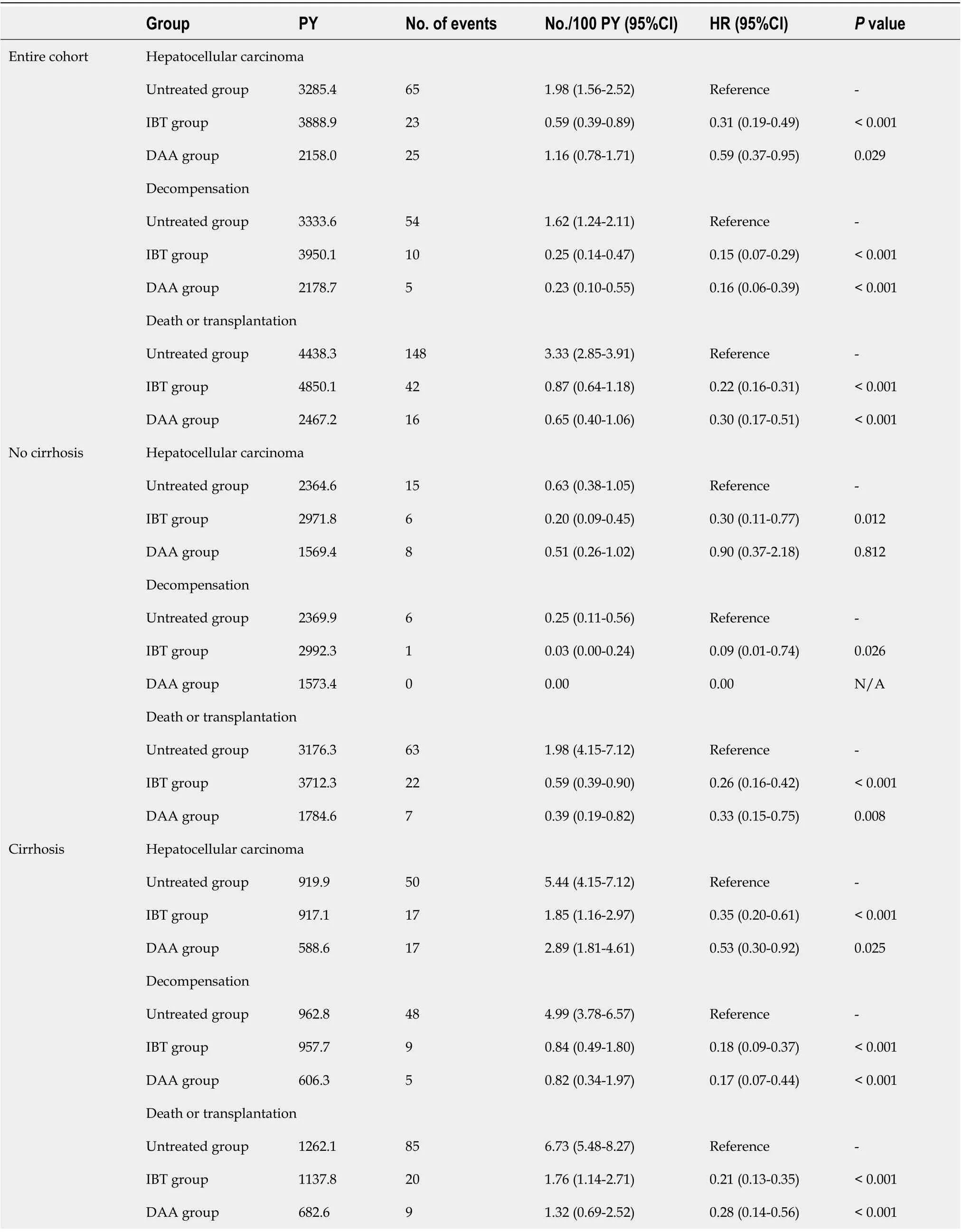

Comparison of the clinical outcomes of the IBT-SVR group and DAA-SVR group in the SVR cohort:Unadjusted and PS-matched results

The SVR cohort comprised 1,268 chronic HCV patients who achieved SVR with IBT or DAA (IBT-SVR group,n= 451; DAA-SVR group,n= 817). The SVR rates of the IBT and DAA groups were 67.5% and 95.3%, respectively. The baseline characteristics at the time of initiation of treatment of the IBT and DAA groups according to SVR are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The incidence rates of HCC,decompensation, and death/LT were significantly lower in the IBT-SVR group than in the IBT-no SVR group (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, the incidence rate of death/LT was significantly lower in the DAA-SVR group than in the DAA-no SVR group, whereas the incidence rates of HCC and decompensation did not reach statistical significance, probably because of the short follow-up or rare incidence of decompensation (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2 Annual incidence rates of hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensation and death/transplantation according to treatment exposure and the presence of cirrhosis

Table 3 Multivariate time-varying Cox regression analysis for hepatocellular carcinoma and death/transplantation in entire cohort

Total bilirubin, mg/dL 0.96 (0.81-1.13)0.6241.03 (0.99-1.08)0.156--PT, INR 2.53 (1.02-6.28)0.0444.42 (1.48-13.20)0.0082.69 (1.22-5.92)0.014 AFP, log10 ng/dL 2.10 (1.46-3.02)< 0.0011.48 (0.90-2.44)0.121.17 (0.86-1.60)0.32 Total number of patients, 2197; number of hepatocellular carcinomas, 113; number of deaths, 202; number of transplantations, 4; number of decompensations, 69. AFP: Alpha-feto protein; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratio; BMI: Body mass index; CI: Confidence interval; DAA: Direct acting antivirals;HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IBT: Interferon-based therapy; PT: Prothrombin time; SVR: Sustained virologic response.

In the SVR cohort (5880.4 patient-years), 30 patients developed HCC, 6 patients had decompensation,35 patients died, and no patient underwent LT during follow-up. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC at 2 and 5 years were 0.6% and 1.6%, respectively for non-cirrhotic patients with SVR (n= 985),and 4.8% and 10.1%, respectively, for cirrhotic SVR patients (n= 283). The cumulative HCC risk according to the presence of cirrhosis, FIB-4 index, APRI score, and ALBI score were significantly different (Supplementary Figure 3). However, HBcIgG positivity (HR, 0.39; 95%CI: 0.05-2.89;P= 0.358)and the presence of fatty liver disease (HR, 0.16; 95%CI: 0.02-1.18;P= 0.072) were not significant risk factors for the development HCC.

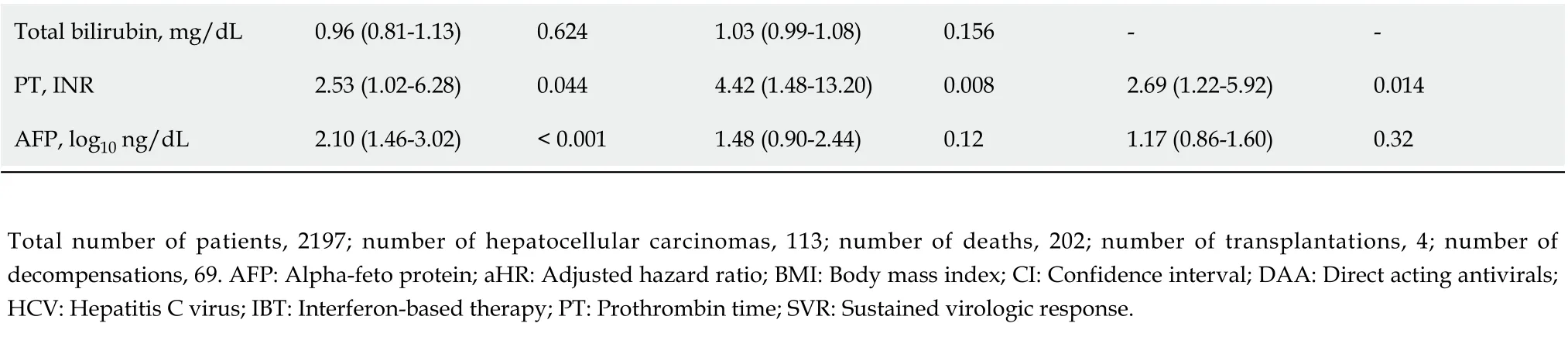

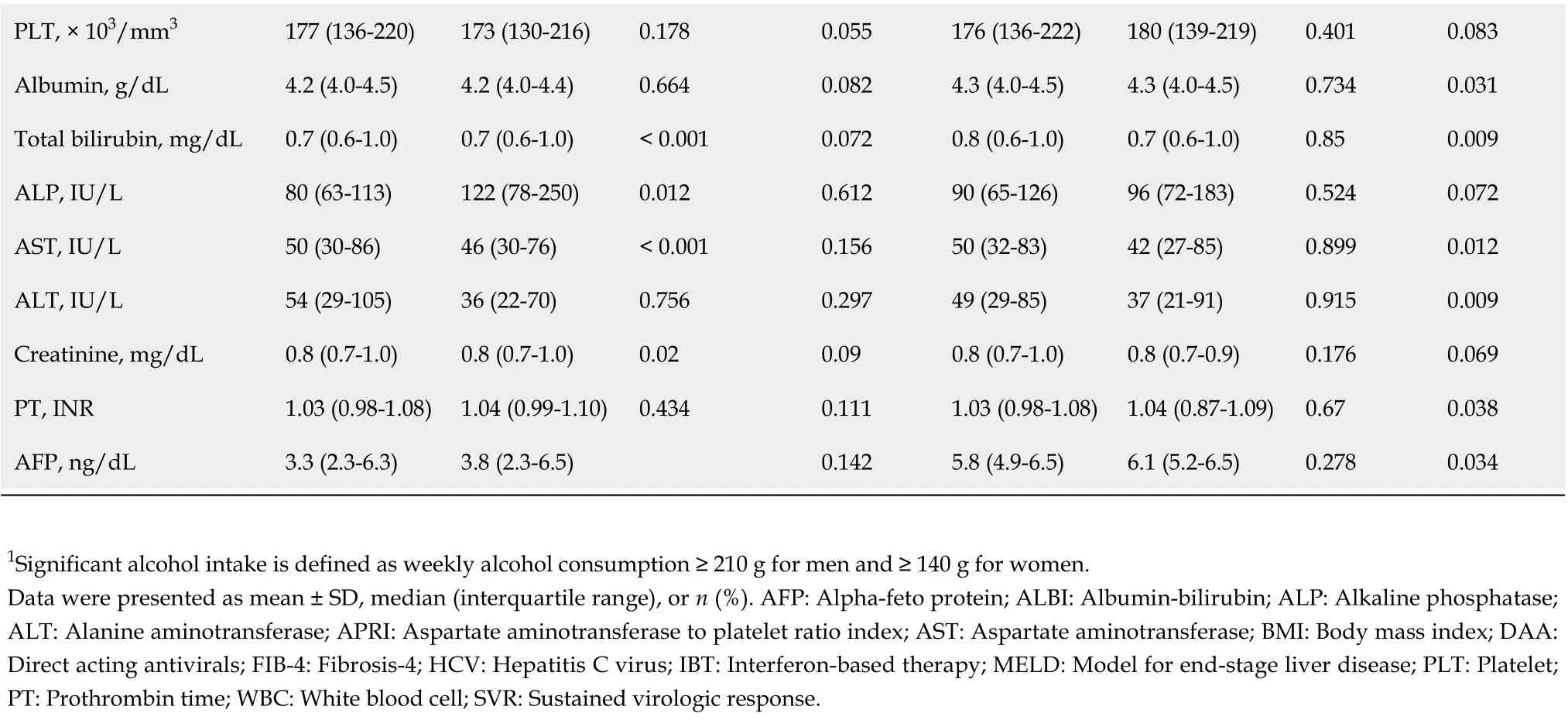

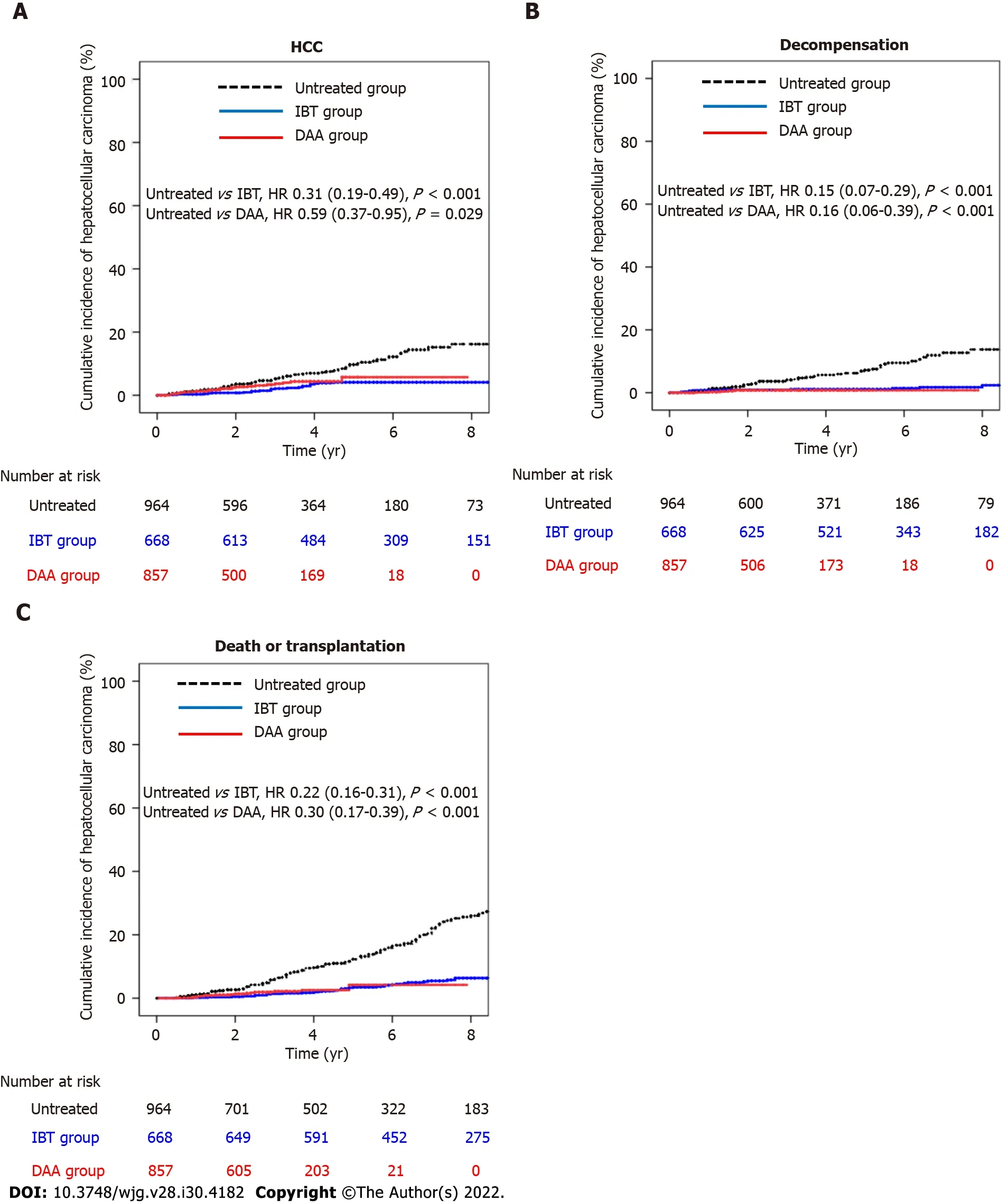

Comparisons of the clinical characteristics and outcomes of the IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups before and after PS matching (Table 4) yielded 213 matched pairs of patients from the IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups with no significant between-group differences in all baseline variables. Before PS matching, the DAA-SVR group had a significantly higher risk of HCC than the IBT-SVR group (HR, 3.53; 95%CI: 1.47-8.49;P= 0.005) (Supplementary Figure 4A), whereas the risks of decompensation (HR, 2.45; 95%CI: 0.33-18.37;P= 0.382) and death/LT (HR, 1.44; 95%CI: 0.62-3.34;P= 0.400) did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Figure 4B and C). However, after PS matching, the DAA-SVR group showed no significant differences in the risks of HCC (HR, 2.72; 95%CI: 0.63-11.81;P= 0.179),decompensation (HR, 9.74; 95%CI: 0.42-224.81;P= 0.155), and death/LT (HR, 2.18; 95%CI: 0.47-10.15;P= 0.318) compared with the IBT-SVR group (Figure 3).

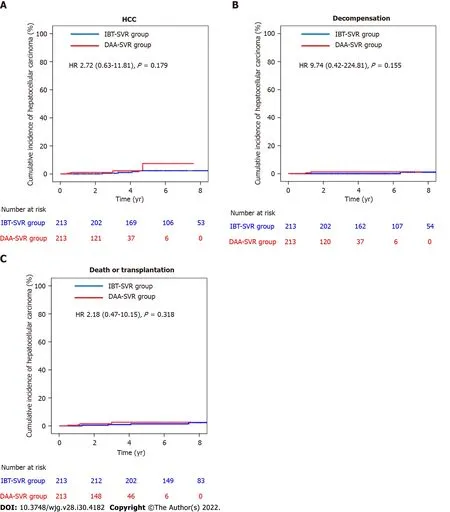

Multivariable-adjusted analyses of factors associated with outcomes of the SVR cohort

According to the multivariable-adjusted analysis, the DAA-SVR group did not show any independent differences in the development of HCC (HR, 2.03; 95%CI: 0.76-5.43;P= 0.160) or death/LT (HR, 1.38;95%CI: 0.55-3.49;P= 0.494) compared with the IBT-SVR group (Table 5). Covariates independently associated with a higher incidence of HCC were older age (HR, 1.05; 95%CI: 1.01-1.10;P= 0.025),genotype 1 (HR, 3.02; 95%CI: 1.18-7.68;P= 0.021), and the presence of cirrhosis (HR, 3.18; 95%CI: 1.33-7.68;P= 0.009) after adjustment for the antiviral treatment regimen, sex, alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, albumin level, PT, and AFP level (Table 5). Additionally, covariates independently associated with death/LT risk were the presence of cirrhosis (HR, 2.97; 95%CI: 1.42-6.20;P= 0.004) and PT (HR,5.27; 95%CI: 1.01-27.53;P= 0.049).

DlSCUSSlON

We analyzed the incidence rates of HCC, decompensation, and all-cause death/LT in a large,prospective, Asian cohort including 2054 patients with chronic HCV infection. During a median followup period of 4.1 years, the risks of HCC, decompensation, and all-cause mortality were significantly lower after treatment with IBT or DAA compared with no treatment.

After statistical adjustment, including a time-varying Cox analysis and PS-matched analysis, the risks of HCC, decompensation, and all-cause mortality were not significantly different regardless of whether SVR was achieved after IBT or DAA treatment; however, the follow-up duration of the DAA group was shorter than that of the IBT group. After achieving SVR, independent factors associated with HCC risk were no treatment, age, male sex, HCV genotype 1, cirrhosis, alcohol consumption, PT, and pretreatment AFP level, whereas independent factors associated with all-cause mortality were cirrhosis and PT.

There are limited studies of the association between antiviral treatment (IBT or DAA) and all-cause mortality, especially those involving Asian cohorts. Many studies focused on liver-related mortality rather than all-cause mortality as the primary outcome after SVR achievement. However, extrahepatic mortality should be considered for patients with HCV because HCV is associated with increased cardiovascular disease events[20] and extrahepatic malignancies such as bile duct cancers and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[21,22]. Moreover, Tadaet al[23] reported that IBT could reduce all-cause mortality and HCC risk even in patients who did not achieve SVR. However, the effect of DAA treatment in the absence of SVR on clinical outcomes is unknown. Therefore, this study focused on the effect of treatment on the outcomes including all-cause mortality in the entire cohort, and the effect of SVR induced by IBT and DDA on the outcomes in the SVR cohort.

Table 4 Comparison of characteristics and outcomes between the interferon-based treatment-sustained virologic response and directacting antivirals-sustained virologic response groups: Unadjusted and propensity score matching groups

PLT, × 103/mm3 177 (136-220)173 (130-216)0.1780.055176 (136-222)180 (139-219)0.4010.083 Albumin, g/dL 4.2 (4.0-4.5)4.2 (4.0-4.4)0.6640.0824.3 (4.0-4.5)4.3 (4.0-4.5)0.7340.031 Total bilirubin, mg/dL 0.7 (0.6-1.0)0.7 (0.6-1.0)< 0.0010.0720.8 (0.6-1.0)0.7 (0.6-1.0)0.850.009 ALP, IU/L 80 (63-113)122 (78-250)0.0120.61290 (65-126)96 (72-183)0.5240.072 AST, IU/L 50 (30-86)46 (30-76)< 0.0010.15650 (32-83)42 (27-85)0.8990.012 ALT, IU/L 54 (29-105)36 (22-70)0.7560.29749 (29-85)37 (21-91)0.9150.009 Creatinine, mg/dL 0.8 (0.7-1.0)0.8 (0.7-1.0)0.020.090.8 (0.7-1.0)0.8 (0.7-0.9)0.1760.069 PT, INR 1.03 (0.98-1.08)1.04 (0.99-1.10)0.4340.1111.03 (0.98-1.08)1.04 (0.87-1.09)0.670.038 AFP, ng/dL 3.3 (2.3-6.3)3.8 (2.3-6.5)0.1425.8 (4.9-6.5)6.1 (5.2-6.5)0.2780.034 1Significant alcohol intake is defined as weekly alcohol consumption ≥ 210 g for men and ≥ 140 g for women.Data were presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or n (%). AFP: Alpha-feto protein; ALBI: Albumin-bilirubin; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase;ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: Body mass index; DAA:Direct acting antivirals; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IBT: Interferon-based therapy; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; PLT: Platelet;PT: Prothrombin time; WBC: White blood cell; SVR: Sustained virologic response.

Table 5 Multivariate Cox regression analysis for hepatocellular carcinoma and death/transplantation among the sustained virologic response cohort

Recent 5-year follow-up studies after DAA treatment showed that SVR is associated with a gradual but significant reduction in liver fibrosis in terms of FIB-4, METAVIR, transient elastography, and Child-Pugh score[24,25], whereas another study showed that induced SVR was associated with a reduced risk of clinical disease progression in patients with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis but not in patients with Child-Pugh B/C cirrhosis[26]. In this context, our study showed an approximately 85% reduction in the risk of decompensation after IBT or DAA treatment in Child-Pugh A patients, with decompensated cirrhotic patients being excluded from enrollment.

Figure 2 Cumulative incidences of hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensation, and death/transplantation in entire cohort. A: Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the untreated, interferon-based treatment (IBT), and direct-acting antivirals (DAA) groups; B: Cumulative incidence of decompensation in the untreated, IBT, and DAA groups; C: Cumulative incidence of death/transplantation in the untreated, IBT, and DAA groups. DAA: Direct-acting antivirals; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; IBT: Interferon-based treatment.

Figure 3 Cumulative incidences of hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensation, and death/transplantation in the matched sustained virologic response cohort. A: Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the interferon-based treatment-sustained virologic response (IBT-SVR) and direct-acting antivirals-sustained virologic response (DAA-SVR) groups; B: Cumulative incidence of decompensation in the IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups; C:Cumulative incidence of death/Liver transplantation in the IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups. DAA: Direct-acting antivirals; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; IBT:Interferon-based treatment; SVR: Sustained virologic response.

This study demonstrated that treatment with IBT and DAA resulted in risk reductions of 72%(median follow-up, 94.8 mo) and 81% (median follow-up, 42 mo) for all-cause mortality, respectively,compared with no treatment after multivariate adjustment. Similar to previous studies[27], our results showed that even IBT, with its probable adverse events and lower SVR rates, had long-term beneficial effects on mortality. Regarding the benefit of DAA treatment, Buttet al[28] (n= 6790), using the Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans (ERCHIVES) data in the United States in 2017, reported that DAA treatment and the achievement of SVR reduced all-cause mortality by 57% and 43%, respectively, within the first 18 mo of treatment. A prospective cohort study performed in France (n= 9895; follow-up, 33.4 mo) reported a 52% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality in the DAAtreated group compared with the untreated group in 2019[11]. Compared with these studies, our results showed a higher reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality with DAA treatment. This may be related to the low proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis in the DAA group in our cohort. Additionally, the follow-up duration of this study was relatively longer than the durations used for those studies.

During this study, the achievement of SVR by IBT or by DAA resulted in a 59% reduction in the risk of HCC compared with no treatment or no SVR after multivariable adjustment, similar to previous studies[29,30]. Nonetheless, our results also showed that the HCC risk remained after SVR achievement.Despite the achievement of SVR, the absolute risk of HCC remains high for patients with cirrhosis;therefore, according to international guidelines, they should be enrolled in an HCC surveillance program[2-4]. However, there is little evidence of the benefits of HCC surveillance for non-cirrhotic chronic HCV patients with SVR, because of the low residual HCC risk. During this study, the noncirrhotic group had an HCC risk of 0.26 per 100 person-years (5-year cumulative incidence of 1.6%). In particular, the low FIB-4 (5-year cumulative incidence of 0.3%) group had a very low risk of HCC during this study. These results are similar to those of the retrospective REAL-C cohort study that targeted Eastern Asians (5-year cumulative incidence: 1.35 for the non-cirrhotic group and 0.13 for the low FIB-4 group)[30]. These results support the European guidelines, which do not recommend HCC surveillance for fibrosis 0 to 2[4]. However, more long-term follow-up data after achieving SVR are needed.

Identifying the risk factors associated with HCC after SVR is important to the development of a reasonable surveillance strategy. An East Asian retrospective study suggested that among the cirrhotic DAA-SVR group, age older than 60 years, ALBI scores of 2 or 3, and pretreatment AFP > 10 ng/mL were associated with HCC risk; however, among the non-cirrhotic group, only AFP > 10 ng/mL was significant[30]. Additionally, there are many factors associated with HCC risk after SVR, such as clinical factors (age, sex, presence of diabetes, HCV genotype 3, history of IBT), laboratory parameters (platelet count, AFP), and fibrosis stage (determined by histology or estimation by Fibroscan?, FIB-4, APRI, or the presence of esophageal varices) before DAA treatment and at follow-up (determined by Fibroscan?, FIB-4, APRI, alanine aminotransferase, AFP, albuminemia, or VITRO score)[31]. In our study, age, cirrhosis,and HCV genotype 1 (compared with genotype 2) were independent risk factors for HCC after SVR.Therefore, it is necessary to test the HCV genotype even in the therapeutic era of pangenotypic regimens to develop a follow-up strategy after SVR according to the regional distribution of HCV genotypes.These factors should be considered when establishing an optimal HCC prediction model.

Previous studies have suggested a similar risk of HCC development with IBT and DAA treatment[32]. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis suggested that IBT is better than DAA for preventing the occurrence of HCC in chronic hepatitis C patients after achieving SVR[33]. Biologically, IFN family members, especially class I IFN (IFN-α, IFN-β), have important anti-HCC effects[32]. However, some investigators have suggested that the sudden decrease in viral load caused by DAA treatment causes immune distortion, thus deregulating the antitumor response and releasing precancerous foci from immune surveillance[34,35]. Although it can be explained theoretically, there is little clinical evidence regarding the difference in the HCC risk for patients with DAA-SVR and IBT-SVR. Our results showed significant clinical differences between the IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR groups. Both the multivariable analysis and PS matching analysis showed that the effect of IBT-SVR was not different from that of DAA-SVR on the HCC incidence and all-cause mortality. Recently, some studies reported different effects of IBT-SVR and DAA-SVR on the incidence of diabetes[36] and hematologic malignancies[37].Therefore, long-term studies of the effects of DAA-SVR are warranted.

To meet the 2030 HCV elimination target of the WHO[1], active testing and enhanced linkage to treatment are important. In this study, 30.1% of patients remained untreated, and this percentage should be reduced. Indeed, the untreated group showed a higher mortality rate of 23.7% (88 Liver related deaths and 59 non-liver related deaths) during the median follow-up of 5.6 years. In the untreated group, 3 patients received IBT after HCC diagnosis, and 19 patients received DAA treatment after HCC diagnosis or a decompensation event. The majority of the untreated patients (78.8%, 457/619) were enrolled in the Korean HCV cohort before June 2015, when the first DAA was introduced, and 46.7%(289/619) died or were lost to follow-up before June 2015. Although DAA therapy is covered by the National Health Insurance System, 30% of the drug price is an out-of-pocket expense of the patients,equaling to approximately 3000 United States dollars. Even in the DAA era, the main reasons for nontreatment are the relatively high price of DAA, old age, and extrahepatic or advanced hepatic malignancy.

One of the strengths of our study was that it was a long-term study involving a prospective, Asian cohort that included both IBT and DAA groups. This study used a well-established protocol, guidelines and database, and the data, including death outcomes, were verified under government guidance. To date, few reports have evaluated and compared clinical outcomes (HCC, death, and decompensation)after IBT and DAA treatment, especially in Asia, where HCV is less prevalent than HBV.

This study had several limitations. First, because it was an observational study, the findings may show selection and confounding biases. Despite this limitation, it would be useful for comparing the effectiveness of IBT and DAA because of the relatively low incidence of clinical events. Second, we used clinical and radiological criteria to diagnose cirrhosis; therefore, some patients with advanced fibrosis may have been included in the non-cirrhotic group. However, we attempted to correct this point using a non-invasive liver fibrosis biomarker. Third, there was a disparity in the follow-up periods of the IBT and DAA groups because of the later introduction of DAA (since 2015 in Korea). Additional long-term follow-up studies evaluating the outcomes of patients with SVR are warranted. Forth, the presence of anti-HBc IgG in HCV patients has been implicated in HCC development, and a non-negligible risk of HBV inactivation during DAA treatment (0.91%)[38]. However, approximately 30% of our patients were not tested for anti-HBc IgG, and none of the anti-HBc IgG-positive patients were tested for HBV DNA during DAA treatment. Likewise, the role of fatty liver in the outcomes of HCV patients was not completely evaluated owing to missing data. Finally, compared with the IBT era, diagnostic imaging modalities and treatment options for HCC have improved in the DAA era. Therefore, these points could have affected the clinical outcomes of the IBT and DAA groups.

CONCLUSlON

This study showed that antiviral treatment significantly reduced the incidences of HCC,decompensation, and mortality in an Asian population, regardless of the use of IBT or DAA. After achieving SVR, age, the presence of cirrhosis, and HCV genotype 1 were indicators of worse clinical outcomes. Therefore, an adequate HCC surveillance strategy after SVR that considers age, the presence of cirrhosis, and genotype should be developed. Additional studies evaluating the long-term DAA outcomes of SVR patients are also warranted.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We deeply appreciate the clinical research coordinators (Lee DE, Kim NH, Jeong DH, Na SM, Kang HY,Jo AR, Han SH, Chung ES, Jeong HY, and Lee HM) for their dedication to this study and the officials of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (Lee MS, Seong JH, Lee JK, Kee MK, Chung HM,Choi BS, Kim KS, Kang C, Kim SS, and Jee YM) for their strong support of this study.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Choi GH and Jang ES contributed equally to this work; Choi GH, Jang ES, and Jeong SH were responsible for the study concept and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, and manuscript drafting; Kim YS, Lee YJ, Kim IH, Cho SB, Lee HC, and Jang JW assisted with data acquisition and analysis; Ki M, Choi HY, and Baik D assisted with the data analysis and interpretation.

Supported bythe Chronic Infectious Disease Cohort Study (Korea HCV Cohort Study) from the National Institute of Infectious Disease, National Institute of Health, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, No. 2020-E5104-02.

lnstitutional review board statement:The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of seven hospitals.

lnformed consent statement:All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Nothing to declare.

Data sharing statement:We are not willing to share data.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:South Korea

ORClD number:Gwang Hyeon Choi 0000-0002-8795-8427; Eun Sun Jang 0000-0003-4274-2582; Sung Bum Cho 0000-0001-9816-3446; Han Chu Lee 0000-0002-7631-4124; Jeong Won Jang 0000-0002-0305-5846; Sook-Hyang Jeong 0000-0002-4916-7990.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Yan JP

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年30期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年30期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Alcohol-related diseases and liver metastasis: Role of cell-free network communication

- Benefits of minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of gastric cancer

- Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of a traumatic neuroma of the extrahepatic bile duct: A case report and review of literature

- ANGPT: Angiopoietin; VEGFA: Vascular endothelial growth factor; PGF: Placental growth factor; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; IQR: Interquartile range; SD:Standard deviation, SE: Standard error.

- Network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on esophagectomies in esophageal cancer: The superiority of minimally invasive surgery

- Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil