Epidemiology of stomach cancer

Milena Ilic, Irena Ilic

Abstract Despite a decline in incidence and mortality during the last decades, stomach cancer is one of the main health challenges worldwide. According to the GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates, stomach cancer caused approximately 800000 deaths(accounting for 7 .7 % of all cancer deaths), and ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in both genders combined. About 1 .1 million new cases of stomach cancer were diagnosed in 2020 (accounting for 5 .6 % of all cancer cases). About 75 % of all new cases and all deaths from stomach cancer are reported in Asia.Stomach cancer is one of the most lethal malignant tumors, with a five-year survival rate of around 20 %. There are some well-established risk factors for stomach cancer: Helicobacter pylori infection, dietary factors, tobacco, obesity, and radiation. To date, the most important way of preventing stomach cancer is reduced exposure to risk factors, as well as screening and early detection. Further research on risk factors can help identify various opportunities for more effective prevention. Screening programs for stomach cancer have been implemented in a few countries, either as a national or opportunistic screening of high-risk individuals only. Generally, due to its high aggressiveness and heterogeneity,stomach cancer still remains a severe global health problem.

Key Words: Stomach cancer; Epidemiology; Incidence; Mortality; Survival; Predictive factors; Prevention

INTRODUCTION

Stomach cancer was the fifth most common malignant tumor in the world in 2020 with approximately 1 .1 million new cases, and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death, with around 800000 deaths[1 ,2 ].Over 85 % of stomach cancer cases are registered in countries with high and very high Human Developing Index (590000 and 360000 cases, respectively)[1 ]. The highest number of cases of stomach cancer (almost 820000 new cases and 580000 deaths) was registered in Asia (mainly in China)[1 ,2 -4 ]. The estimated five-year survival rate is lower than 20 %[2 ,5 -8 ].

Worldwide, stomach cancer incidence and mortality correlate with increasing age and are relatively rare in persons of both gender younger than 45 years[2 ,4 ,7 ]. The frequency of stomach cancer in men is approximately double that in women[1 -3 ]. In men, stomach cancer was the most commonly diagnosed cancer in 2020 in seven countries (all countries were in Asia: Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan,Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Кyrgyzstan, and Bhutan) and the leading cause of death from cancer in ten countries (Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Кyrgyzstan, and Bhutan in Asia, Mali and Cape Verde in Africa, Colombia and Peru in South America, and Costa Rica in Central America)[1 ,2 ]. Although stomach cancer was not the most diagnosed cancer in women in any country, stomach cancer was the leading cause of death from cancer among females in three countries (Tajikistan, Bhutan, and Peru)[1 ,2 ]. The incidence and mortality rates from stomach cancer were generally low in Northern America and Northern Europe in 2020 and equivalent to rates registered across most of the African regions[1 ,2 ].

In the first half of the 20thcentury, gastric cancer was the leading cause of death from malignant tumors in the United States and Europe[9 ,10 ]. Over the past decades, the incidence and mortality due to stomach cancer have substantially declined in many countries[1 ,2 ].

Stomach cancer is a multifactorial disease[9 -12 ], including both lifestyle and environmental risk factorsHelicobacter pylori(H. pylori) infection, low socioeconomic status, dietary factors, such as high intake of salty and smoked food and low consumption of fruits and vegetables, fiber intake, in addition to tobacco smoking, alcohol use, low physical activity, obesity, radiation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, positive family history and inherited predisposition. However, the etiology of stomach cancer has not yet been sufficiently elucidated.

Topographically, stomach cancer is classified into two subsites: cardia stomach cancer (arising from the upper stomach) and noncardia stomach cancer (arising from the other parts of the stomach), which differ in epidemiologic patterns and etiology[13 ]. The majority of all stomach cancers (approximately 90 %) are adenocarcinomas, while other types (including lymphoma, sarcoma, neuroendocrine tumors)are rare[12 ,14 ]. Two major histologic types of stomach cancer adenocarcinomas are diffuse and intestinal, which differ in epidemiological peculiarities, such as age at diagnosis, gender ratio,etc.[15 ,16 ].

Despite the strong declining trends in incidence and mortality, stomach cancer remains an important part of the global burden of cancer. Many of the risk factors remain insufficiently understood and need to be the focus of further research in order to achieve more specific, targeted prevention measures.

INCIDENCE

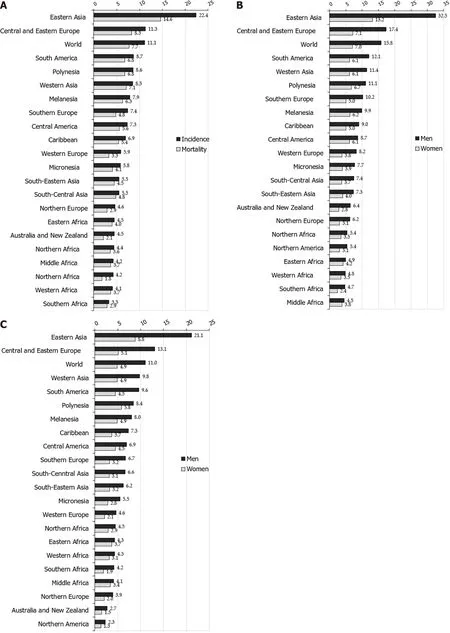

Worldwide, there is a considerable geographic variation in stomach cancer incidence. Stomach cancer incidence rates in 2020 were highest in Eastern Asia (22 .4 per 100000 people), followed by Central and Eastern Europe (11 .3 per 100000 people), and South America, Polynesia and Western Asia (equally about 8 .6 per 100000 people) (Figure 1 A)[2 ]. The lowest rate (3 .3 per 100000 people) was registered in Southern Africa.

More than three quarters (75 .3 %; 819944 ) of all stomach cancer cases are residents of Asia[2 ]. Most(86 .7 %; 944591 cases) stomach cancer cases were residents of more developed regions. The least number of stomach cancer cases was recorded in Micronesia/Polynesia.

Figure 1 Stomach cancer incidence and mortality, by regions. A: Stomach cancer incidence and mortality; B: Stomach cancer incidence in men and women; C: Stomach cancer mortality in men and women. GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates[2 ]: Age Standardized Rate (using World standard population, per 100000 ).

Notable variations in the incidence of stomach cancer in 2020 , as well as for mortality, exist around the world (Figures 1 -4 )[2 ]. The highest incidence rates were recorded in countries of eastern Asia(Mongolia, Japan, Republic of Кorea), while the highest death rates were observed in countries of western Asia (Tajikistan, Кyrgyzstan, Iran). The lowest incidence and mortality rates of stomach cancer were recorded in Northern America and Northern Europe, Australia/New Zealand and some African countries. Patterns in females were broadly similar to those observed in males, but large differences were observed between sexes and throughout different countries/regions (Figures 1 -4 )[2 ]. Globally, the incidence rate of stomach cancer in males was 15 .8 per 100000 in 2020 , and in females 7 .0 per 100000 (Figure 1 B)[2 ]. The gastric cancer incidence rates were about 2 to 3 times higher in males than in females(ranging from 32 .5 per 100000 in Eastern Asia to 4 .5 per 100000 in Middle Africa for men, and in women ranging from 13 .2 in Eastern Asia to 2 .4 in Southern Africa) (Figure 1 B)[2 ]. By countries, the differences were fifty-fold: the incidence rates of gastric cancer in men ranged from 48 .1 per 100000 in Japan to 1 .0 per 100000 in Mozambique in 2020 (Figure 2 A). Also, similar differences were observed by regions: the highest incidence rates were reported in Eastern Asia (Japan: 48 .1 , Mongolia: 47 .2 , Republic of Кorea:39 .7 ), while the lowest rates were recorded in South Africa (Mozambique: 1 .0 , Lesotho: 2 .1 ). The incidence rates of stomach cancer in women ranged from 20 .7 per 100000 inhabitants in Mongolia(followed by Tajikistan: 18 .7 , Republic of Кorea: 17 .6 and Japan: 17 .3 ) to about 0 .5 in Indonesia and Mozambique in 2020 (Figure 2 B).

However, the distribution of stomach cancer did not have a clear geographical pattern: namely, even though the highest risk populations in the world are in Asian countries (e.g.Japan, Mongolia, Republic of Кorea), some other countries in Asia register relatively low rates (such as Sri Lanka, Indonesia,Thailand) (Figure 2 A and B)[2 ]. On the other hand, in some low-risk populations, there are some highrisk groups for stomach cancer, such as Кoreans and Japanese who live in the United States[17 ,18 ].

Also, rates varied across races. Stomach cancer incidence in men in the United States was highest in blacks, followed by Asians/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indian/Alaska natives[7 ]. In women, the highest rates were registered in Hispanics, followed by blacks and Asian/Pacific Islanders,and American Indian/Alaska natives. In the United States, for both sexes, the lowest rates were recorded in whites.

Also, incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in all indigenous groups exceeded the frequency among their non-indigenous counterparts: the highest gastric cancer rates were registered in Indigenous Siberians, Mapuche in Chile and among Alaskan Inuit[19 ]. Additionally, increasing incidence trends were observed in some indigenous groups, especially in Inuit residing in the circumpolar region and in Maori in New Zealand.

Although differences in stomach cancer incidence in different parts of the world are still not fully clear, most of the variation in stomach cancer incidence worldwide is due to variations in exposure to environmental or lifestyle related risk factors[20 -22 ]. Additionally, migrant studies[23 ] and secular trends of gastric cancer rates also indicate that environmental factors have an important role in the etiology of gastric cancer[24 ]. The most important established risk factor for gastric cancer is infection withH. pylori[25 ]. Internationally, variations inH. pyloriinfection prevalence show similarities with variations in stomach cancer prevalence; in developing countries,H. pyloriinfection prevalence in adults is 76 % vs 58 % in developed countries[26 ]. The prevalence was estimated to be 77 .6 % in South Africa,55 .8 % in China, 52 .2 % in Mexico, 24 .6 % in Australia and 22 .1 % in Denmark[27 ]. In the United States of America, the prevalence in non-Hispanic blacks was 53 %, in Mexican Americans was 62 %, but was 26 %among non-Hispanic whites[28 ]. In part, the geographical variation ofH. pyloriinfection rates correlate with the frequency of stomach cancer across populations. On the other hand, certain highly infected populations (e.g.in Africa and South Asia), unlike the East Asian countries, do not have a high incidence of stomach cancer, which can be explained, at least in part, by the differences in prevalence of genotypes ofH. pylori(in East Asian the vacA m1 genotype is predominant, whereas the m2 genotype predominated in Africa, South Asia, and Europe)[29 ].

Additionally, several other environmental factors are also considered as contributors to gastric cancer occurrence[21 ,22 ,30 ]. Differences between sexes and international variations could likely be due to tobacco smoking[31 ]. Based on the Global Burden of Disease study[22 ], the drop in burden of stomach cancer was associated with improved Socio-demographic Index, then to high-sodium diet in both genders combined, as well as to smoking in males, in particular in east Asian populations.

In addition, some research points to the role of aging[24 ] and hereditary and genetic factors[6 ] in stomach cancer burden. Incidence differences by sex have never been fully explained, but some theories have suggested a protective role of female sex-specific hormones[15 ,32 ]. A higher stomach cancer incidence in males than in females may be due to differences in the incidence of different subtypes of adenocarcinoma according to histology (intestinal or diffuse) and location (proximal or distal)[12 ,13 ,33 ].Diffuse adenocarcinoma is more common in younger and female patients, whereas intestinal adenocarcinoma is more common in males and the elderly[15 ]. Intestinal adenocarcinoma dominates high-risk areas and is considered responsible for much of the international variation in incidence. The observed differences in stomach cancer incidence worldwide could be due to diagnostic capacity and changes in the quality of registries, where coverage, completeness and accuracy vary by country[34 ].

MORTALITY

Nearly three quarters of stomach cancer deaths (74 .8 %; 575206 deaths) were registered in Asia[2 ]. Most(83 .7 %, 643609 deaths) of those who died due to stomach cancer were residents of more developed regions. The least number of deaths were recorded in Micronesia/Polynesia.

Stomach cancer mortality varies greatly across populations and regions. Mortality rates for stomach cancer in 2020 in both genders were highest in the Eastern Asia region (14 .6 per 100000 people),followed by South America, Polynesia, Western Asia and Central and Eastern Europe (equally about 8 .5 per 100000 people) (Figure 1 A)[2 ]. The lowest mortality rates (about 2 .0 per 100000 people) were registered in Northern Africa and Australia. The differences in mortality rates were thirty-fold between the population with the highest rate (Mongolia - 24 .6 ), and the one with the lowest rate (Mozambique -0 .7 ).

Stomach cancer mortality by gender shows significant geographic variations[1 ,2 ,6 -8 ]. Globally, the mortality rate of stomach cancer in males in 2020 was 11 .0 per 100000 , and in females 4 .9 per 100000 (Figure 1 C)[2 ]. The region with the highest mortality rates due to stomach cancer in 2020 in both genders was Eastern Asia (21 .3 and 8 .8 per 100000 , respectively) (Figure 1 C)[2 ]. The lowest rates of stomach cancer mortality in both sexes were in North America (2 .3 and 1 .3 per 100000 , respectively). In men, the risk of dying from stomach cancer was highest in Mongolia (36 .5 ), followed by Кyrgyzstan,Tajikistan and China (approximately 25 .0 per 100000 ) (Figure 2 C). By contrast, the risk of death from stomach cancer was lowest in men in Mozambique (1 .0 ) and Indonesia (1 .9 ). Women living in Tajikistan and Mongolia had the greatest risk (approximately 15 .0 per 100000 ) of death from stomach cancer, while the risk for women in Indonesia and Mozambique was lowest (less than 1 .0 per 100000 ) (Figure 2 D).

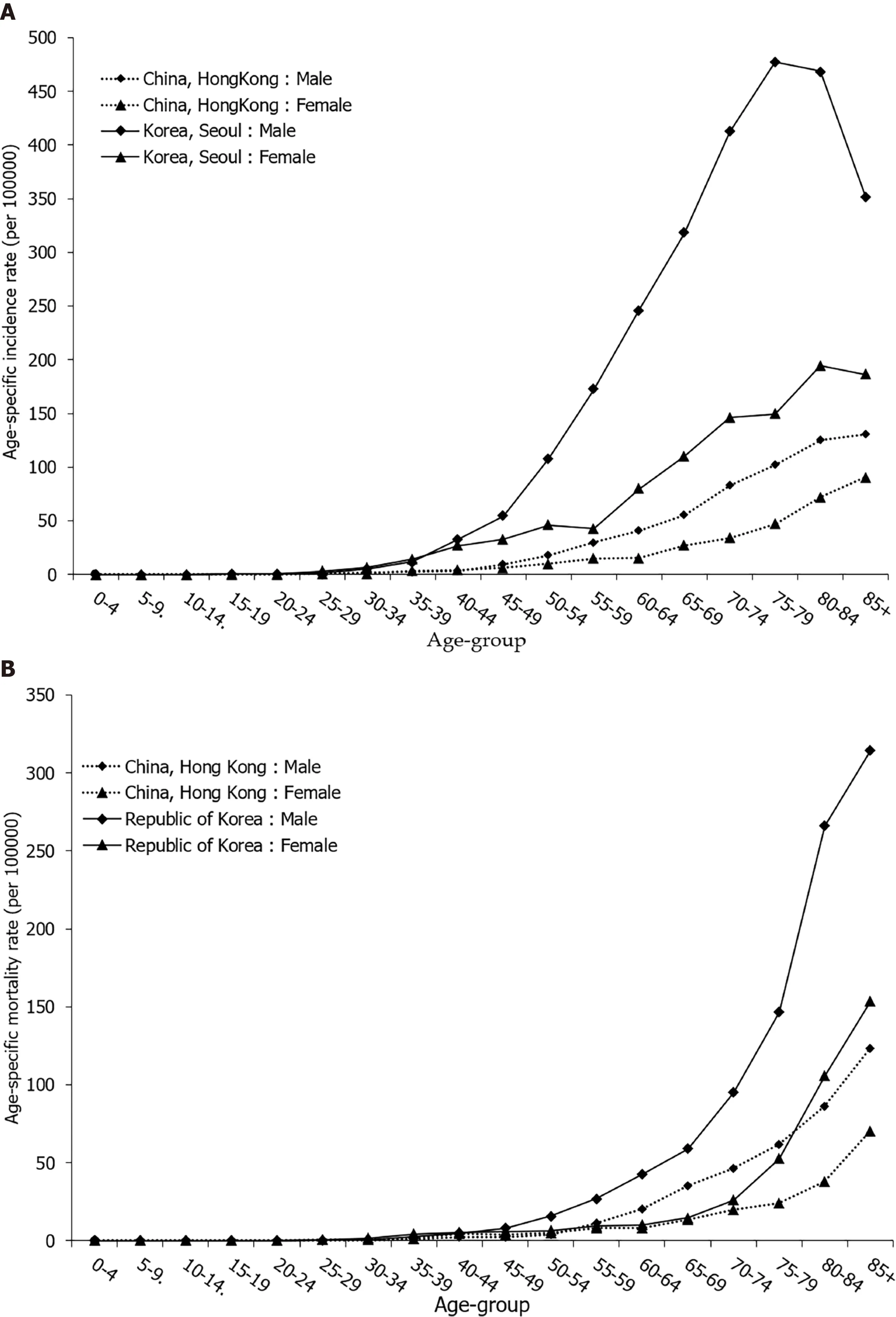

Gastric cancer mortality rates begin to rise in middle-aged persons, with the highest rates observed in the elderly (aged 75 years and older) age group for both males and females (Figure 4 B).

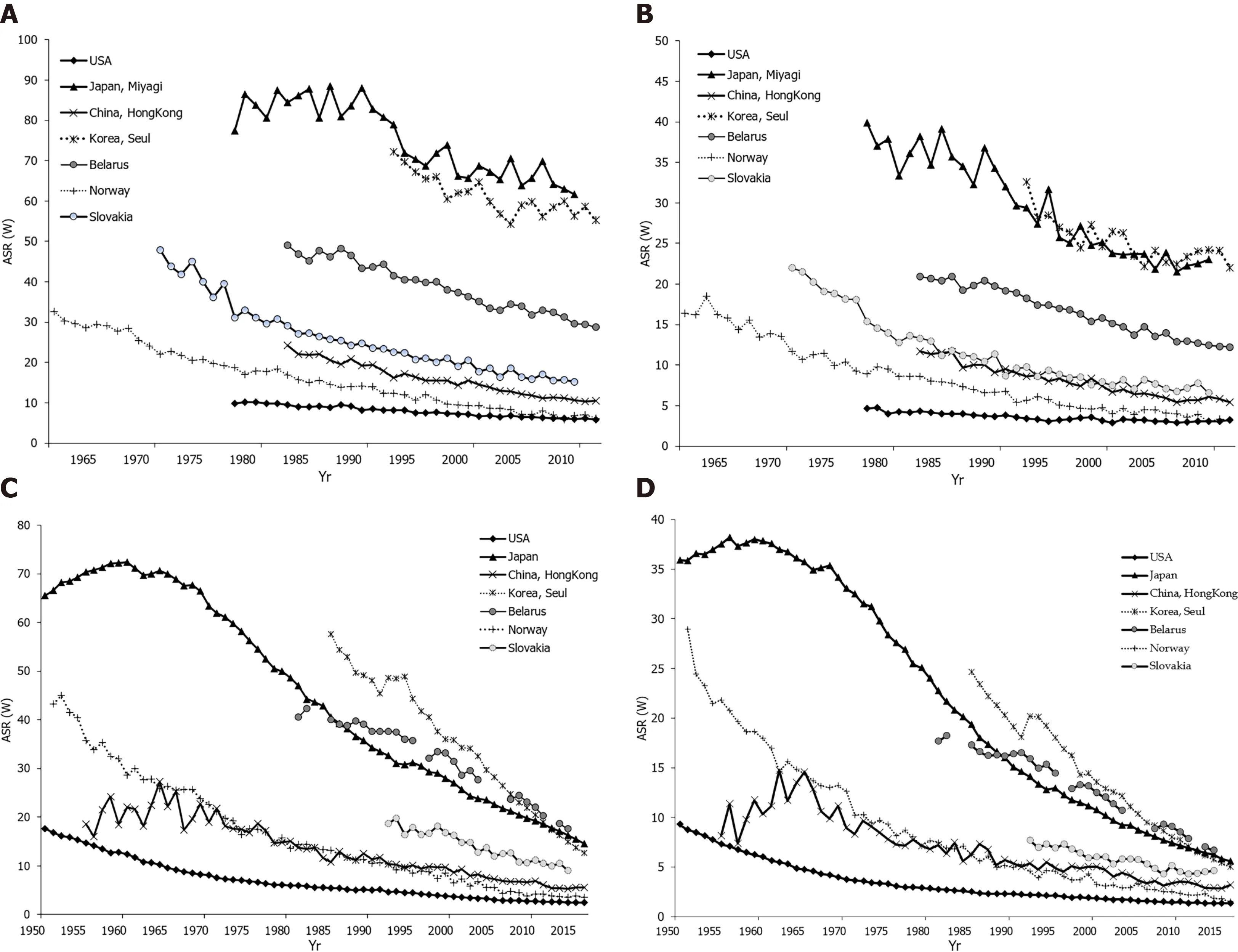

Figure 3 Stomach cancer incidence and mortality trends. A: Stomach cancer incidence trends among men in selected countries; B: Stomach cancer incidence trends among women in selected countries; C: Stomach cancer mortality trends among men in selected countries; D: Stomach cancer mortality trends among women in selected countries. GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates[2 ]. Age Standardized Rate (using World standard population, per 100000 ).

Stomach cancer mortality showed apparent geographical variability. Generally, the large differences in mortality rates are between developing and developed countries. Considering developed countries,this mortality pattern could be explained by increased hygiene standards, dissemination of food refrigeration, better preservation of food, high intake of fresh fruits and vegetables and eradication ofH.pylori[11 ,22 ,35 ]. In the second decade of the 21stcentury in Japan, mortality due to stomach cancer reached the levels of Western countries (Figure 4 B), which could be attributed to the introduction of gastric cancer screening and to changes in lifestyle, such as the reduction in salt use and an increase in the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, improvement in food storage, smoking reduction and prevention of infection withH. pylori[22 ,36 ,37 ]. However, reasons for the significant international variations in stomach cancer mortality rates are not fully clear. Diffuse adenocarcinoma is more common in females, while intestinal adenocarcinoma is dominant in males, this subtype being responsible for most of the international variations[15 ].

There is a wide variation in the relative contribution of cardia and noncardia cancers to the overall number of stomach cancer cases, with a higher proportion of cardia cancers in countries with lower stomach cancer incidence and mortality rates (such as the United States, Canada and Denmark)[38 ]. In males in Europe, the proportion of cardia and noncardia stomach cancers ranged between 11 .6 %(Belarus) and 72 .0 % (Finland), with higher proportions observed in Northern Europe and lower proportions in Eastern Europe. Among other countries worldwide, the proportion of cardia stomach cancers ranged between 5 .8 % (Republic of Кorea) and 64 .8 % (Iran). In females, a similar geographic pattern was observed, although rates were lower: in Europe, the proportion of cardia and noncardia stomach cancers ranged between 10 .6 % (Italy) and 44 .5 % (United Кingdom), while worldwide it ranged from 4 .3 % (Republic of Кorea) to 31 .5 % (Australia).

Low incidence rates of stomach cancer, which notably became a rare diagnosis among the white United States population, are attributed to the “unplanned triumph” of prevention, which involves a decreasedH. pyloriprevalence and improved food storage and preservation[9 ,39 ].

Cancer mortality data are influenced by data on incidence, as well as the success of treatment.Although the World Health Organization estimates present detailed and high-quality information on the incidence and mortality of stomach cancer recorded by cancer registries (regional or national)around the world, these estimates should be interpreted with considerable caution, due to the limited quality and coverage of cancer data worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries, due to issues of local data quality, registry coverage, and analytical capacity[2 ,40 ,41 ]. The effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cancer burden is not yet clear, particularly taking into consideration the geographical variations and evolution of the pandemic across countries (because of the lockdown, possible delays in cancer diagnoses,etc.)[2 ].

The differences in availability of improvements in stomach cancer diagnosis and treatment may have had some role in the observed variations in mortality rates worldwide, but this contribution remains open to further quantification[42 ]. Screening programs and early detection of stomach cancer which have been implemented in Japan[43 ] and in Кorea[44 ] can partly explain the differences in mortality rates. Also, in Japan, advancements were made in the surgical treatment of early disease, resulting in a better survival rate compared to other countries[45 ]. However, stomach cancer survival remains unacceptably low in most areas of the world[46 ,47 ].

The high prevalence ofH. pyloriinfection is widely recognized as the key contributor to high rates of stomach cancer mortality[48 ]. There is abundant evidence that exposure to other risk factors (tobacco,diet, alcohol use,etc.) may have contributed to the apparent international differences in mortality rates of gastric cancer[49 -51 ]. Also, disparities in socio-economic status could have an influence on stomach cancer mortality rates, mediated by varying exposures to infection, environmental factors, as well as barriers in accessing medical care[22 ,52 ].

TEMPORAL TRENDS

Declining gastric cancer incidence rates are the dominant epidemiological pattern globally[1 ,2 ]. Figures 3 A and B show data, for males and females, on stomach cancer incidence secular trends for selected populations. In both sexes, the underlying pattern was a rapid decline in incidence rates over the whole considered time period, regardless of the background stomach cancer risk. There were two exceptions to this pattern. The first exception was seen in the Japanese population (Miyagi prefecture) where, particularly in males, very high rates were observed until the 1990 s, and then declined but remained high.The second exception was for the United States population where over the entire time period the rates were constantly very low. The exact reason for the decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the last few decades is not completely known, but it most likely includes improvements in diet, food storage and declining prevalence of infection withH. pyloridue to a general improvement in sanitation and increased use of antibiotics[53 ]. Eradication ofH. pylorican be achieved with antibiotic therapy; but, the treatment of asymptomatic carriers is not practical because many countries have a very high infection burden (e.g., over 75 % of adult persons living in sub-Saharan Africa haveH. pyloriinfection) and reinfection is relatively easy[54 ,55 ]. Figure 3 C and D represent secular trends for stomach cancer mortality, for males and females, in selected countries over the period 1961 to 2016 [2 ]. Also, downward trends for stomach cancer mortality rates show a very similar pattern as well as incidence trends. In men, the steep decreasing trends for stomach cancer mortality were observed in all selected countries continuously over the observed period. Two exceptions to the mortality pattern were seen. The first exception was for Slovakia where, particularly in women, the rates showed a slower downward trend up to the 2000 s, with a flattening of the mortality trend from the 2010 s onwards. The second exception was for the United States population where mortality rates remained constantly very low over the entire time period. Stomach cancer mortality in both women and men has shown a significant declining trend in most developed countries over the past 50 years[1 ,2 ]. A similar trend, although starting later, has been seen in some countries in Asia, such as Japan and China[37 ,50 ]. Factors that led to a decline in mortality involve increased availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, reduced use of salt, reduced incidence ofH. pyloriinfection due to improved hygiene and use of antibiotics, and the implementation of screening programs[56 ,57 ].

By age, incidence and mortality patterns for stomach cancer in women were broadly similar to those in men, regardless of the background stomach cancer risk being high or low (Figure 4 ). In selected countries, stomach cancer was predominantly a disease of the elderly, and almost 90 % of all cases were diagnosed after the age of 55 years (Figure 4 A). For both sexes, stomach cancer mortality continuously increases with age, and is two times higher in those older than 70 years (Figure 4 B).

The favorable trend of stomach cancer incidence in developed countries could largely be attributed to a decrease inH. pyloriprevalence: this is reflected by the “birth cohort effect” where in some countries(including Кorea, Japan, the United States) rates ofH. pylorihave been declining in younger generations[24 ,34 ,38 ]. Intestinal adenocarcinoma dominates high-risk areas and is considered responsible for much of the variation in incidence. Recent studies indicate an increase in gastric cancer incidence (cardia and noncardia stomach cancers combined) in persons under the age of 50 in both low- and high-risk countries (such as the United Кingdom, the United States, Canada, Belarus, Chile)[58 ]. The increasing prevalence of autoimmune gastritis and dysbiosis of the stomach microbiome could have contributed to the increase in stomach cancer incidence among younger generations[59 ].

In both men and women, trends in the prevalence of cigarette smoking are related to trends in incidence and mortality of stomach cancer with a lag of roughly several decades[22 ,60 ]. Besides,stomach cancer mortality trends were minimally influenced by changes in the coding of this disease in the second half of the twentieth century[61 ].

Figure 4 Stomach cancer incidence and mortality trends by age and sex. A: Stomach cancer incidence trends by age and sex in selected countries in 2012 ; B: Stomach cancer mortality trends by age and sex in selected countries in 2016 . GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates[2 ].

SURVIVAL

In general, survival for patients with stomach cancer is poor[5 ,62 ]. In addition, there is global variation in stomach cancer survival[34 ,47 ]. Worldwide, with the exception of Japan and Кorea, most areas have an overall 5 -year relative survival of stomach cancer of about 20 %-30 %[63 ]. A 5 -year relative stomach cancer survival rate of about 20 % is observed in Western developed countries and in developing countries according to an international comparison of data from population based cancer registries[64 -66 ]. In contrast to North America and Europe[66 ], stomach cancer survival is higher in East Asia: e.g., 5 -year survival rate is 67 % in Кorea and 69 % in Japan[67 ,68 ], followed by Jordan (56 %) and Costa Rica(46 %) in 2010 -2014 [69 ]. Also, a notable increase in stomach cancer survival was seen in China (from 30 .2 % to 35 .9 %) in recent years[69 ]. These differences are in part explained by the early stomach cancer detection due to the screening programs implemented in East Asia[63 ]. The relatively high overall survival for stomach cancer in Japan is the result of a high proportion of patients being diagnosed in the early stage of the disease: in 1995 -2000 , 53 % of stomach cancers were diagnosed at an early stage in Japan[70 ] in contrast to about 27 % in the United States[71 ]. Differences in tumor biology and stomach cancer subtype (with East/Central Asia and Eastern Europe having a larger proportion of noncardia stomach cancers than North America and Western Europe) may also contribute to survival differences[8 ,46 ,72 ,73 ]. Worldwide, the proportion of cardia stomach cancers, indicating worse prognosis, ranged from 6 % in South Кorea to 72 % in Finland for men, and for women it ranged from 4 % in South Кorea to 52 % in Serbia[38 ]. Similarly, cases with the intestinal subtype had a higher survival rate than patients with diffuse tumors[70 ]. Many factors influence the survival of stomach cancer, including the type of cancer, stage at diagnosis, age, sex, race, overall health, and lifestyle[74 -76 ]. Generally, due to high aggressiveness and heterogeneity, stomach cancer still remains a severe global health problem[47 ,77 ].

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Stomach cancer is a multifactorial disease. The notable international variation, time trends, and the migratory effect on stomach cancer frequency suggest that environmental and lifestyle factors are very important in the development of this disease.

In 1994 , the International Agency for Research on Cancer has classifiedH. pyloriinfection as a carcinogen in humans due to the evidence which linksH. pyloriinfection and risk of gastric cancer[48 ].H. pylorias a carcinogen most likely acts indirectly, by causing gastritis, which is a precursor to stomach atrophy, metaplasia, and dysplasia. While the risk of stomach cancer correlated with the duration ofH.pyloriinfection, no association was found for the histologic subtype of stomach cancer (intestinal or diffuse), or sex. Based on a meta-analysis of cohort studies, the risk of stomach cancer in people withH.pyloriinfection was 2 .36 [78 ]. Chronic or recurrentH. pyloriinfection is a major cause of stomach cancer;the relative risk is estimated to be 2 .7 -3 .8 for cancer of cardia, and 1 .1 -11 .1 for noncardia stomach cancer[20 ]. H. pylori infection is attributed to 592000 (63 .4 %) of all cases of stomach cancer globally[26 ].H.pyloriis a stomach colonizing bacterium; howH. pyloriis transmitted has not been elucidated definitely,but the person-to-person pathway is most likely a contact pathway[48 ].H. pyloriinfection is acquired in childhood, and population prevalence is associated with socioeconomic status[79 ]. High prevalence ofH. pyloriinfection, and little international variation, suggest that other factors are important in the etiology of gastric cancer[53 ]. The main risk factors for noncardia stomach cancer areH. pyloriinfection,tobacco smoking and dietary factors, while gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity and possibly tobacco smoking play an important role in the development of cardia gastric cancer[6 ,9 -13 ,22 ].

The main cofactors responsible for the development of stomach cancer are smoking and diet[30 ,31 ,80 -82 ]. After adjusting for alcohol intake or the presence of chronicH. pyloriinfection in the stomach, an independent association with smoking was confirmed[83 ,84 ]. Over 45 case-control studies and 27 cohort studies confirmed the association of tobacco with stomach cancer, with the average relative risk being RR = 1 .5 -2 .0 [85 ]. One recent meta-analysis of prospective observational studies suggests that the summary relative risk was higher in men (1 .63 ) than in women (1 .30 )[31 ]. The risk of stomach cancer increases significantly with cigarette smoking (40 % for smokers and 82 % for heavy smokers) and alcohol consumption[86 ]. It is estimated that in developing countries the gastric cancer risk attributable to smoking is 11 % in men and 4 % in women, while in developed countries the risk is 17 % in men and 11 % in women[85 ,87 ].

While some authors believe that diet has no role in the etiology of gastric cancer, the American Cancer Society states that smoked foods, salted fish and meat, and pickled vegetables represent risk factors for gastric cancer[88 ]. Some bacteria, likeH. pylori, can convert nitrates and nitrites (commonly found in meat products) to substances which are shown to cause gastric cancer in animals[48 ,89 ]. It is also known that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is significantly inversely correlated with gastric cancer[89 ,90 ].

The correlation between salt intake (high in salt, smoked foods, salted fish and meat) and stomach cancer risk has been indicated in several epidemiological studies[91 -94 ]. Sodium chloride is known to increase gastrocarcinogenesis using N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in a rat experiment[95 ], as well as in a human study[96 ]. The mucin layer which covers and protects the stomach epithelium is damaged by high doses of salt, which also cause high osmotic pressure that further damages epithelial cells. Prolonged damage to the mucous membrane leads to chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, which are precursors for stomach cancer.

Higher consumption of fruits and vegetables has been associated with a lower risk of malignant tumors in a number of epidemiological studies (over 200 case-control and cohort studies)[97 ,98 ], while results are particularly numerous and consistent for stomach cancer[99 ]. The intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, which contain antioxidant vitamins (e.g.vitamins A and C), reduces gastric cancer risk. In a cohort of 900000 adults (404576 men and 495477 women) who were not diagnosed with malignancy at the time of enrollment, 57145 people died after 16 years, with the highest weight subjects having a higher mortality rate from malignant tumors in general: men had a 52 % higher rate, and women a 62 %higher rate, compared to people with normal body weight[100 ]. Higher mortality was found for esophageal, colon, liver, gallbladder, pancreatic and kidney cancer, but also for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), especially with the long-standing forms, had a significantly increased risk for cardia stomach cancer and the majority of studies noted a 2 -4 -fold increase in risk[10 ,101 ,102 ], although not all[103 ]. One of the explanations for the association between GERD and cardia gastric cancer is that GERD may cause metaplasia with potential progression to adenocarcinoma[104 ]. On the other hand, a lack of association between GERD and noncardia stomach cancer might be explained, at least in part, by the association with atrophic gastritis which might be associated with a decrease in gastric acid secretion and lower risk of GERD[105 ].

Of the demographic factors, socio-economic status, older age and male gender play an important role[9 -11 ]. Socio-economic deprivation, within any population, is consistently linked with increased gastric cancer risk[106 ,107 ]. The risk of developing stomach cancer increases with age[7 ,34 ]. Stomach cancer rarely develops before the age of 40 , more than 80 % of stomach cancers occur between 60 and 80 years of age. Stomach cancer affects men more than women[1 -3 ]. The consistency of risk difference by sex has never been adequately explained although possible explanations included differences in environmental exposures and lifestyle factors, as well as the theory regarding the potentially protective role of female sex-specific hormones[108 ]. According to the results of studies conducted in the United States, stomach cancer occurs more often in African Americans compared to the white population[7 ]. Possible reasons for this increased risk include socioeconomic factors, prevalence ofH. pyloriinfection, cigarette smoking,and obesity[7 ,22 ,109 ,110 ].

It is estimated that around 10 % of stomach cancer cases aggregate in families, and only 1 %-3 % are hereditary[10 ,13 ,111 ]. A positive family history of stomach cancer in a first-degree relative is a risk factor for stomach cancer, but the magnitude of risk varies with different ethnic groups and geographic regions, ranging from 2 to 10 [112 ,113 ]. Although familial aggregation could be a risk factor because of shared genetic factors, the influence of shared environment cannot be ruled out,e.g., passage ofH. pyloriinfection from parents to children, the same dietary factors,etc.Although migrant studies indicate a significant reduction in the risk of gastric cancer in Japanese immigrants, the results of many studies point out that exposure to environmental factors in childhood is important for determining gastric cancer risk[48 ,53 ,79 ]. Namely, migrant studies show that exposure in childhood is important in stomach cancer etiology:e.g.infection withH. pylorioften occurs before the age of 10 ,i.e.often before the migration, also children born in the immigrant country are likely to acquire the infection from family members who have migrated from their native country[114 ].

Gastric cancer risk is increased in many genetic disorders, such as hereditary diffuse gastric cancer,Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and familial adenomatous polyposis[10 ,112 ]. Persons who have mutations or deletion in genes such asp53 , BRCA2 , MSH2 , and MLH1 , have an increased risk of stomach cancer[10 ,111 ].

Some studies found a link between stomach cancer and antioxidant use, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, physical activity, and radiation[6 ,9 -13 ]. Some researchers have suggested a correlation between the excess or deficit of iodine, goiter, and stomach cancer, as well as a decrease in stomach cancer mortality after performing effective iodine prophylaxis[115 ].

Other potential risk factors in relation to stomach cancer include poor oral hygiene and tooth loss[116 ], hookah and opium use[117 ], Epstein-Barr virus infection[118 ], and consumption of pickled vegetables[119 ], but the results are not convincing, at least not yet. In addition, in many persons with stomach cancer there is no one specific stomach cancer risk factor.

PREVENTION

During the past century, Western developed countries experienced a major reduction in stomach cancer incidence and mortality, without the introduction of specific primary and secondary prevention measures. Generally, favorable trends in the frequency of stomach cancer are thought to be an important part a consequence of changes such as the reduction in the use of salt and an increase in the consumption of fruit and fresh vegetables due to improvements in food storage (refrigerators, freezers).This phenomenon has been dubbed the “unplanned triumph” of prevention[9 ,39 ].

Primary and secondary prevention strategies are the focus of stomach cancer prevention.

Primary prevention measures involve improvements in environment and lifestyle habits such as tobacco control/smoking cessation, reducing salt intake, increasing fruit and vegetable intake,developing other healthy behaviors (such as Mediterranean diet, higher intake of fiber, physical activity),H. pylorieradication, other medications (intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,statins), refraining from high alcoholic beverages, sanitation and hygiene improvements. The WHO has set a global goal of reducing the intake of salt to less than 5 g (2000 mg of sodium) per person per day by the year 2025 [120 ]. A meta-analysis of randomized trials (all trials were performed in areas with a high incidence of stomach cancer, mostly in Asia), in a total of 6695 participants followed from 4 to 10 years showed that the risk of stomach cancer can be reduced by 35 % with the treatment of H. pylori[121 ]. In addition to endoscopic and histological surveillance, the American and European guidelines recommend eradication ofH. pyloriin all persons who have atrophy and/or intestinal metaplasia and all persons who are first-degree relatives of stomach cancer patients[122 ,123 ]. According to the Asian Pacific Gastric Cancer Consensus, population-based screening and treatment ofH. pyloriinfection is recommended in regions which have an annual stomach cancer incidence of more than 20 /100000 [124 ].Eradication ofH. pylorican be achieved with antibiotic therapy; but, the treatment of asymptomatic carriers is not practical as many countries have a very high infection burden (e.g., over 75 % of adult persons living in sub-Saharan Africa haveH. pyloriinfection) and reinfection is relatively easy[54 ].

Japan has had a national endoscopic surveillance program since the early 1970 s because of the high stomach cancer risk[125 ]. It is recommended that all people older than 40 years undergo screening with a double-contrast barium X-ray radiography and endoscopy every year[126 ]. A study in China demonstrated that a preventive intervention which included eradication ofH. pylori, nutritional supplements, and screening (with double-contrast radiography and endoscopy) resulted in a 49 %reduction in relative risk for overall mortality in a high-risk group of individuals[127 ].

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the gold standard for stomach cancer diagnosis and due to its high detection rate it is used for stomach cancer screening in high-risk areas (such as Japan, Кorea,Venezuela and other areas), but the available evidence shows that endoscopic surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions showed conflicting results[128 ]. Besides, the procedure is expensive,unpleasant for the patient and carries a risk of hemorrhage and perforation[129 ,130 ].

Stomach cancer screening might be possibleviathe detection of potential markers of gastric atrophy(a stomach cancer precursor lesion)[125 ,131 ,132 ], including serum pepsinogens, serum ghrelin,H. pyloriserum antibodies, gastrin-17 , or antigastric parietal cell antibodies, but the results are not convincing, at least not yet.

CONCLUSION

Worldwide, stomach cancer incidence and mortality have declined significantly during the past five decades. However, stomach cancer remains a global health problem as the fifth leading cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world. Further illumination of risk factors can help identify various opportunities for prevention. Primary and secondary prevention strategies with more effectiveness are needed in order to reduce stomach cancer incidence and mortality, particularly in populations with a high burden of stomach cancer.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:All authors equally contributed to this paper with conception and design of the study,literature review and analysis, drafting and critical revision and editing, and approval of the final version.

Conflict-of-interest statement:No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:Serbia

ORCID number:Milena Ilic 0000 -0003 -3229 -4990 ; Irena Ilic 0000 -0001 -5347 -3264 .

S-Editor:Zhang H

L-Editor:Webster JR

P-Editor:Yu HG

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年12期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年12期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Spinal anesthesia alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by modulating the gut microbiota

- Near-infrared fluorescence imaging guided surgery in colorectal surgery

- Epidemiological, clinical, and histological presentation of celiac disease in Northwest China

- Microbiologic risk factors of recurrent choledocholithiasis postendoscopic sphincterotomy

- Similarities, differences, and possible interactions between hepatitis E and hepatitis C viruses: Relevance for research and clinical practice

- Emerging role of colorectal mucus in gastroenterology diagnostics