AbdominaI waII procedures: the bene fits of prehabilitation

Nathan Knapp, Breanna Jedrzejewski, Robert Martindale

1Division of Gastrointestinal and General Surgery Department of Surgery, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA.2Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA.

Abstract Prehabilitation for abdominal wall procedures provides an opportunity to further modify patient risk factors for surgical complications. It includes interventions that optimize nutrition, glycemic control, functional status, and utilization of the patient’s microbiome pre-, intra-, and postoperatively. Through a multidisciplinary and anticipatory approach to patients’existing co-morbidities, the physiological stress of surgery may be attenuated to ultimately minimize perioperative morbidity in the elective setting. With increasing data to support the ef ficacy of prehabilitation in optimizing surgical outcomes and decreasing hospital length of stay, it is incumbent on the surgeon to employ these practices in elective abdominal wall reconstruction. Further research on the effects of prehabilitation interventions will help to shape and inform protocols that may be implemented beyond abdominal wall procedures in an effort to continually improve best practices in surgical care.

Keywords: Prehabilitation, perioperative optimization, abdominal wall reconstruction, minimize co-morbidities

INTRODUCTION

Achieving optimal surgical outcomes for ventral hernia repairs (VHRs) is inherently challenging. Patients who require complex reconstruction of the abdominal wall are commonly overweight, deconditioned,malnourished with or without sarcopenia, and are often chronically infected/in flamed in the setting of the previously placed synthetic mesh. Most patients in need of reconstruction have had prior repairs/recurrences or have other significant comorbidities affecting their surgical fitness. Optimizing surgical outcomes and minimizing perioperative morbidity in this patient population requires careful preparation and planning.

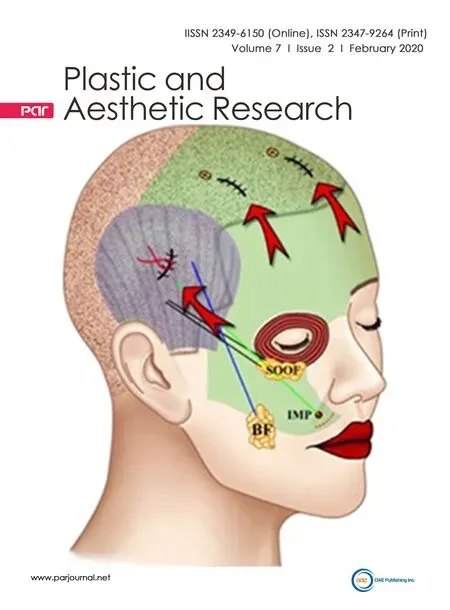

Figure 1. The vicious hernia cycle[10]

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The burden of VHR and abdominal wall reconstruction (AWR) is increasing not only with regards to incidence but also in the case complexity, contributing to overall higher rates of complications[1,2].While infection remains the most common postoperative complication, the issue of hernia recurrence is arguably the most commonly discussed and used to monitor the success of an outcome[3-6]. Following each subsequent repair, the risk of recurrence is linear to and directly related to the number of repairs[7].The financial burden for complications status post hernia surgery are signi ficant: patients with recurrent hernias constitute a minority (15%) of the AWR patient population, yet account for half of the total spending for hernia surgery[1]. Recurrent hernia patients tend to be older with more signi ficant medical comorbidities, and are associated with higher hospital and post-discharge health care costs such as readmissions, emergency department visits, etc. The magnitude of increased financial burden is likely under-reported as other expenses are more difficult to capture and quantify, including skilled nursing facilities, long-term acute care, wound care, home health services, and hospital readmissions to hospitals other than that of the primary procedure[8]. Perioperative surgical site occurrence (infection, seroma,and wound ischemia/dehiscence) increases the risk of hernia recurrence at least three-fold[5]. Surgical site infection (SSI) has been shown not only to be independently associated with an increased rate of SSI at subsequent operation in an otherwise clean wound bed, but also to act as a marker of increased case complexity[9]. A vicious cycle often develops whereby a ventral herniorrhaphy can lead to an unfortunate pattern of bacterial infection, hernia recurrence, reoperation, and hospital readmission [Figure 1][10]. With an increasing emphasis placed on readmission to determine reimbursement, this cycle looms even larger on the minds of hernia surgeons[11]. Therefore, the surgeon should consider optimization of any and all factors that can promote optimal patient recovery.

THE METABOLIC EFFECTS OF SURGERY

Large hernia repairs and AWR result in considerable surgical stress that induce a predictable sequence of metabolic and physiologic changes in the patient. Further evaluation of these metabolic changes highlights areas for intervention that may allow the patient to respond to the stress with a more favorable physiologic state in the perioperative period. Immediately following surgical incision, the body initiates a response on multiple levels, including the neuroendocrine system, the sympathetic system, and the hypothalamicpituitary axis. This concert of effects leads the body to tilt toward a catabolic state to provide a metabolic substrate for mounting an acute phase response to the surgical trauma.

Table 1. Surgeon modi fiable risks for preventing complications

Activation of the sympathetic pathway induces a hyperglycemic state via gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Simultaneously, a surge in stress hormones including cortisol, glucagon, prolactin, and growth hormone mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary axis contributes to insulin resistance and therefore an inability for the body to correct hyperglycemia. In the acute perioperative period, persistent hyperglycemia inhibits immune function and thus surgical recovery by driving catabolic changes via cortisol and glucagon, translating to breakdown of skeletal muscle, loss of lean body mass, and signi ficant deconditioning. While a patient’s preoperative physical fitness and young age may also compensate for proteolysis, fat metabolism primarily serves to minimize protein breakdown by mobilizing glycerol and fatty acids for energy usage. However, increased insulin levels and tissue insulin resistance present in times of stress yield a relative decrease in adipose breakdown. Recent literature demonstrates that immune-related nutrients such as glutamine and arginine may be depleted postoperatively and that their replacement may improve surgical outcomes[12]. While the effects on the modulation and attenuation of the in flammatory response to the catabolic effects of surgery by omega-3 fatty acids [eicospentanoic acid(EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)] are well documented, recent data suggest that they also serve as a substrate for production of specialized pro-resolving molecules (SPMs). SPMs not only accelerate the resolution of inflammation, decrease post-surgical pain, and enhance the function of macrophages and neutrophils in bacterial killing and clearance, but they do so without increasing the in flammatory state in the process[13,14]. Thus, micronutrient supplementation with vitamins may be warranted in patients who are unable to resume a balanced enteral diet in the days following surgery.

PREOPERATIVE MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

The preoperative preparation and optimization serve to acknowledge and modify risk factors that may negatively impact surgical outcomes. Table 1 summarizes the factors that are reviewed in this review.

Obesity

Over 60% of AWRs are performed on obese patients[15]and obesity increases the risk of numerous complications, including seroma, dehiscence, fistula, infections, reoperation, and thromboembolic events. Numerous studies by bariatric surgeons con firm the high incidence of incisional hernias as well as increased rates of wound infections in the obese patient population[16]. The reduction of postoperative incisional hernias and wound complications with laparoscopic gastric bypass motivated development of the technique[17]. However, the risk of hernia recurrence has been shown to positively correlate with increased body mass index (BMI) regardless of the type of repair performed[18-20]. While excess weight must be addressed with patients desiring hernia repair, it is not feasible to expect all hernia patients to achieve ideal weight prior to an operation. We have found that hernia recurrence and surgical site occurrence rates are prohibitively high in patients with a BMI > 50. Therefore, at our institution, elective repairs for patients with BMI > 50 are not performed unless they present with acute concern for bowel compromise.

Weight loss counseling should be a routine component of preoperative visits for those patients with BMI > 35.This counseling involves review of speci fic dietary modi fications, exercise regimen, dietician consult, and establishment of realistic weight loss goals. A reasonable rate of weight loss entails 0.5 kg or one pound per week with a 15-30-pound de ficit over 3-6 months. Even with the support of a multidisciplinary clinical team, successful weight loss is greatly variable. Should the patient not meet weight loss goals with dietician support, the date of surgery may be postponed and a referral may be placed to bariatric surgery for evaluation.

In cases where the patient elects to proceed with a weight loss operation, the literature remains split regarding timing of hernia repair. A study using NSQIP data for all VHRs showed an increased risk of infection at 30 days with concurrent VHR and bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y);however, the increased risk did not exceed that expected of dual procedures[21]. Thus, the authors of the review advocated for a combined approach to minimize the morbidity of two otherwise separate procedures. We would agree that, with a relatively small ventral hernia in a patient undergoing a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, the benefit of concurrent repair would outweigh separate anesthetic events. However, in our experience, patients undergoing a gastric bypass or who require AWR have improved outcomes after they experience the full scope of bene fit from bariatric surgery, including, but not limited to, metabolic, endocrine, and hormonal changes, weight distribution, cardiopulmonary enhancement,and increased mobility. In general, we recommend waiting until the patient’s weight has plateaued (typically 18-24 months post-bariatric surgery), and then scheduling a de finitive hernia repair 3-4 months later.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking widely increases the risk of postoperative complications in most procedures, and hernia repair is without exception[22-25]. A recent study using NSQIP data examined 30-day outcomes in patients undergoing elective hernia repairs and showed that current smokers were at increased risk of reoperation,readmission, death, wound, and pulmonary complications[26]. Several studies examining the effects of smoking have found an increase in wound infection rate after hernia surgery and have identi fied smoking as an independent risk factor for the development of incisional hernia after abdominal surgery[23,27,28].Smoking has a multifactorial detrimental effect on wound healing due to its reduction of oxygen tension levels in the blood and tissue, disruption of microvasculature, and alteration in surgical site collagen deposition[29-31]. VHR and AWR involve several components that may compromise wound healing and promote infection such as undermined skin flaps, myofascial advancement flaps, mesh products, reduction of chronically incarcerated hernia contents, and other concurrent gastrointestinal operations such as fistula take-downs. These factors are compounded with problems associated with active tobacco use,further motivating smoking cessation prior to surgery. Establishing the timing of the “l(fā)ast” cigarette is key as smoking cessation at least one month prior to an operation has been shown to reduce the risk of complications[25]. A prospective trial showed that infection rates of compliant patients quickly approach those of nonsmokers after four weeks of abstinence[25]. A systemic review and meta-analysis confirmed the bene fit of smoking cessation on postoperative outcomes and showed that the magnitude of the bene fit rises signi ficantly with each week of cessation up to the four-week mark[32]. While the debate continues regarding nicotine replacement in the preoperative setting due to concern for vasoconstriction and impaired healing, several studies maintain it has no impact on surgical outcomes[29,33].

For all patients who desire elective complex VHR at our institution, we require a minimum of 30 days smoking cessation preoperatively with allowance for nicotine replacement formulations as needed. Urine cotinine (metabolite of nicotine with a longer half-life) is checked at least 2 weeks prior to surgery to allow rescheduling in case of positive testing. Of note, the use of nicotine-replacement products can result in a positive urine cotinine test. If there is serious concern about a patient’s ongoing smoking status, a urine anabasine level can be checked, which is an alkaloid only present in tobacco and not in any replacement products[34].

Glycemic control in perioperative period

Glycemic control pre-, intra-, and postoperatively has been proven essential for reducing complications in elective surgery, particularly infection[35-37]. Hyperglycemia has been shown to have numerous adverse effects at the cellular level including altered chemotaxis, phagocytosis, pseudopod formation, and oxidative burst, all of which prevent neutrophils from functioning optimally[38]. In diabetic patients or those with suspected hyperglycemia, glycemic control should be measured with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which gives an indication of glycemic control over the previous 2-3 months. While a goal HbA1c of 6.5% is ideal, the risk of infection rises signi ficantly at values > 7.5%[35]. Those patients with difficulty in achieving a HbA1c below 7.5% warrant additional education and assistance from an endocrinologist, diabetic nutritionist, and/or diabetes nurse educator.

In the early 2000s, a large randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated that tight glucose control (80-110 mg/dL) resulted in a decrease in ICU and surgical patient mortality giving rise to the popularity of strict glucose regulation[39]. In the years after this study, the risks of hypoglycemia and its complications were found to outweigh the benefits of meticulous glucose protocol (80-110 mg/dL)[40]. Currently,perioperative blood sugar control in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients should aim for 120-160 mg/dL to minimize complication risks[40-42]. Postoperative hyperglycemia remains a signi ficant risk factor for the development of surgical site occurrences; it has been reported that even one episode of serum glucose of >200 mg/dL increases the risk of wound dehiscence[37,43]. Strict protocols for preventing hyperglycemia and glycemic interventions have effectively reduced rates of hyperglycemia and improved outcomes[43,44].

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia refers to a combination of muscle atrophy and replacement by fibrosis or adipose[45]. This degenerative loss of muscle mass is most strongly associated with aging and is commonly a component of underlying pathologic processes such as cancer or liver disease. It may also occur in relatively healthy individuals if they are obese and inactive. Compared to sarcopenia in non-obese patients, sarcopenia in obesity is associated with a decrease in overall survival[46]. Sarcopenia is quantified using computed tomography by measuring a cross-sectional muscle area (cm2/m2) of the paraspinous muscles at the L3 level and comparing the values to sex-speci fic cutoffs[45,47]. The presence of sarcopenia in surgical and critical care patients has been shown to be a predictor of poor outcomes such as surgical site occurrence, length of stay (LOS), and need for rehabilitation[48-53]. Increased ventilator dependence and overall mortality were seen in elderly trauma patients found to be sarcopenic[49]. Some retrospective data with VHR patients show an association of sarcopenia with increased postoperative complications and hernia recurrences[54],whereas other preliminary reviews of prospective data fail to show a signi ficant correlation[55]. The true role of sarcopenia in AWR and VHR requires further investigation, but methods to preserve and improve lean body mass would likely have a positive impact on patient outcomes[56].

Conditioning and prehabilitation

It has been widely accepted that poor physical fitness is associated with poor surgical outcomes. While surgical risk calculators use biometric variables and laboratory data from the NSQIP database to estimate 30-day perioperative risks, quantifying functional status might be a better predictive tool[57]. Reddy et al.[58]found that time to complete a stair climb in a preoperative setting was strongly associated with complication rates after abdominal surgery. The stress of this exercise likely simulates the physiologic demand induced in surgery and may help triage patients for fitness optimization. This concept, known as preconditioning or prehabilitation, serves to improve functional status leading up to an elective operation utilizing a multidisciplinary approach that includes psychological, physical, and nutritional interventions. Numerous studies have been completed over the past decade to investigate the utility of prehabilitation and demonstrate improved preoperative functional capacity[59], rate of return to preoperative function after abdominal surgery[60], and reduction of complication rates in elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair[61].

Given signi ficant heterogeneity in the surgical diseases being studied and the speci fics of the prehabilitation programs, there is some variability in conclusions and no large-scale evidence of one program exists to support its use[62]. Liang et al.[63]completed the first RCT of prehabilitation in VHR patients in 2018.They showed that the prehabilitation group (which consisted of a multidisciplinary consultation with a nutritionist, physical therapist, hernia navigator, weekly group meetings, and daily goals checklists for diet and exercise) were more likely to be without hernia or other complications at one month. A recent study identi fied surgical prehabilitation as an independent predictor of five-year disease-free survival in patients with stage III colorectal cancer[64].

Nutrition

The literature well-establishes that poor nutritional status translates into higher rates of postoperative complications and adverse outcomes for patients undergoing elective surgery[65]. Despite knowledge of this,the surgeon buy-in regarding preoperative nutritional optimization remains lackluster. Few major centers have organized programs to evaluate and manage preoperative nutritional status. Successfully identifying and intervening on nutritionally replete patients in the preoperative setting has potential to signi ficantly decrease complications, length of stay, and readmissions based on multiple RCTs[66-68].

Undernourished patients may be identified through one of several simple screening tools. Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 and Nutrition Risk in Critically Ill (NUTRIC score) are both validated systems that project risk of impairment caused by the metabolic stress of the clinical condition[69]. NUTRIC was initially calculated from six variables: age, APACHE II score, SOFA score, number of comorbidities, days from hospital to ICU admission, and IL-6. The current NUTRIC score has excluded IL-6 and remains validated[70]. It is important to remember these scores are risk assessment scores and not nutritional indicators.

The complexity of a patient’s nutritional evaluation exceeds a single laboratory value. While albumin and prealbumin have historically been used as markers of nutritional status, they lack both the sensitivity and speci ficity for detection of malnutrition. During an in flammatory state, the production of these visceral proteins is decreased, making the relevance of the absolute values of these proteins even more limited after the onset of illness. There are still reliable data demonstrating that low preoperative albumin levels are associated with increased postoperative complications, but it is not clear that malnutrition is de finitively linked to hypoalbuminemia[71].

Adequate energy intake (both total calories and protein) is clearly important for postoperative recovery,and enteral feeding should begin as soon as possible for nearly all surgical patients. For patients in the hospital and recovering from the stress of major surgery, data from interventions on elderly and critically ill patients show that resistance exercise combined with protein goals of 1.5-2.5 g/kg/day optimizes preservation of muscle mass and functional status[72-77].

A more interesting and proactive concept is the use of preoperative nutritional strategies. Preoperative immune and metabolic modulation gained traction following a series of data by Braga et al.[78-80]. and Gianotti et al.[81]in the early 2000s. They demonstrated reduction of complications, LOC, and total cost of hospitalization with delivery of a speci fic “immune-enhancing” formula for five days prior to operation.This “immune-enhancing” formulation contained supplemental amounts of omega-3 fatty acids (DHA and EPA), arginine, and nucleotides. The bene fit of this formula was demonstrated in both well-nourished and undernourished patients. Although the complete range of mechanisms has not been elucidated, several animal models and clinical studies propose improvement of protein kinetics, wound healing, lymphocyte function, M1 to M2 macrophage conversion (transitioning macrophages from pro-inflammatory and microbiocidal functions to more extracellular matrix building and wound healing functions), and blood flow via nitric oxide vasodilation with arginine supplementation[12,13,82-84]. Omega-3 fatty acids/ fish oils dampen the metabolic response to stress, decrease in flammation, regulate bowel motility via vagal efferents, and stimulate the resolution of the in flammatory response by the endogenous production of SPMs[12,13,82,85,86].Several large meta-analyses in the past decade have added support to the use of perioperative metabolic manipulation. This concept has been shown to be beneficial not in the perioperative period but also when given only preoperatively with essentially preparing the host for the metabolic insult of surgery.The overall conclusions from these studies are that immune-enhancing formulations (more so than other nutritional regimens) lead to decreased overall infections, a reduction in hospital LOS, a decrease in overall complication rate[87-90], and one study even reporting a decrease in mortality[91].

Another area of metabolic manipulation that has been explored is preoperative carbohydrate loading,which has shown usefulness mostly in reducing perioperative hyperglycemia/insulin resistance[92,93]. In a standard protocol, patients consume a 300-mL isotonic clear beverage with 50 g of complex carbohydrate three hours prior to surgery to decrease insulin resistance in the perioperative period. The original carbohydrate loading studies administered the isotonic formulations the night prior to surgery and the morning of surgery with the concept of maximally loading the myocardium, liver, and muscle with glycogen. Subsequent studies have shown that the carbohydrate loading the night before surgery is not necessary[94]. Reported outcomes with this regimen include: no increased risk of aspiration, decreased postoperative insulin resistance, maintenance of muscle strength, decreased patient anxiety, and possibly decreased LOS but no major difference in major clinical signi ficant outcomes such as reduced infections or length of stay[95-97]. While the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism consensus guidelines for surgical nutrition endorses carbohydrate loading[98,99], further studies are needed to better elucidate quantity and optimal timing of intervention.

Skin preparation, antibiotics, and the microbiome

The literature suggests that acute changes in the host microbiome may alter metabolism on a systemic level. A majority of surgeons and hospitals instruct patients to shower with chlorhexidine gluconate soap the night prior to and the morning of surgery. A Cochrane Database review in 2015 summarizing seven studies and over 10,000 patients showed that, while they reported a decrease in skin bacterial colonization,there was no reduction of surgical-site infections with use of chlorhexidine compared to other agents[100].Furthermore, a study using prospectively collected data in VHR patients actually suggested the use of prehospital chlorhexidine scrub increases the risk of infection[101]. While preoperative bathing can certainly reduce bacteria counts on the skin, it does not clearly translate into positive impacts on surgical outcomes.It may disrupt normal skin flora and therefore remove the competitive inhibition that usually prevents pathogenic bacteria from proliferating. These antibacterial soaps destroy not only pathogenic bacteria but also commensal strains[102]. However, more research is necessary before making any de finitive changes to standard of care. Our program has eliminated the night before surgery chlorhexidine showers as we believe that the elimination of normal skin flora for long periods before surgery allows potential pathogens to colonize.

The data on the choice of skin preparation in the operating room are more conclusive and stem from two major trials. A prospective trial by Swenson et al.[103]with over 3200 patients demonstrated that iodine skin preparation was superior to chlorhexidine preparations. Then, a prospective randomized trial was published reporting that chlorhexidine was superior to iodine[104]. Swenson and Sawyer[105]then reanalyzed the data from both studies and concluded that the decreased infection rate was related to the alcohol in preparations. Duraprep and Cloraprep had similar infection risk, whereas the iodine preparation without alcohol was associated with higher surgical site infections (SSI) rates.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common culprit in postoperative surgical infections and the rate of chronic colonization in the patient population is rising. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the utility of decolonization prior to a planned operation with signi ficant bene ficial results. A randomized control trial including over 6000 patients evaluated infection rates in those pretreated for 5 days with twicedaily nasal mupirocin and daily chlorhexidine showers to a placebo group[106]. The results showed a 44%decrease in postoperative S. aureus infections in the treated group. Several other prospective trials with the implementation of a prescreening and eradication protocol showed similar reductions in infections in patients undergoing elective orthopedic operations[107]. The logistics of screening and subsequently treating these patients need streamlining, but it is clearly cost-effective if performed according to a protocol.

According to joint guidelines developed by several professional surgical and pharmacist societies,prophylactic antibiotics (a first-generation cephalosporin) should be administered within the first hour before incision to decrease surgical-site infection in patients undergoing routine VHR[108]. Specifically,antibiotic administration should occur as close to incision as possible according to a recent large study using NSQIP data[109]. Antibiotics should be re-dosed during the operation, if necessary, taking into account the half-life of the drug, blood loss, and the use of cell saver. If planned, or inadvertent, violation of the colon occurs during the operation, additional antimicrobial coverage is warranted to cover for Gramnegative species and anaerobes (commonly second-generation cephalosporin or a carbapenem). The BMI of the patient must also be taken into consideration, as many of these VHR patients are obese and therefore require higher than standard doses of antibiotics to reach effective levels. One large survey showed that only 66% of patients with a BMI > 30 received adequate prophylactic antibiotic doses[110,111]. Retrospective and anecdotal literature support continued postoperative antibiotics in the presence of surgical drains,but no high quality or Level 1 data validate this practice[112]. It is important to remain cognizant regarding the drawbacks of prolonged antibiotics use with respect to alteration of the gut microbiome and potential development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile. While the exact ideal duration of antibiotics continues to be debated, prospective studies of prophylactic antibiotics support discontinuation upon skin closure[113-116].

The gut microbiome has been shown to play a key role in the human stress response to critical illness[117-121].When healthy and diverse, the microbiome supports symbiosis, homeostasis, and gut barrier function.The gut microbiome is affected by numerous factors that often arise in this patient population, including administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors, vasopressors, and opioids, as well as decreases in luminal nutrient delivery and even changes to the exposed partial pressure of oxygen if the bowel is opened. Probiotics (live microorganisms which confer bene ficial effects to the host when given in sufficient quantities)[122]and prebiotics (food ingredients which are largely non-digestible fibers that induce the growth of bene ficial microorganisms in the colon) have emerged as potential treatments to help reduce postoperative infections by supporting a healthy gut microbiome. Several randomized controlled trials using pro- and prebiotics have been conducted in various surgical patient populations[123]in an effort to prevent speci fic infections, e.g., MRSA[124]. Numerous high quality meta-analyses make it clear that the use of pro- and prebiotics lowers the rates of SSIs, urinary tract infections, and sepsis[125-128].

Enhanced recovery after surgery, opioid reduction, anxiety, and miscellaneous

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols were first developed in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, but are now used widely throughout surgical specialties. ERAS protocol has resulted in shorter hospitalizations, reduced complication rates, lower readmissions, and lower healthcare costs[129-131]. Having a protocolized and multidisciplinary approach to the care of complex patients, such as AWR patients, in the pre-, intra-, and postoperative settings is clearly the best strategy for success.

Intraoperative wound protectors in abdominal surgery are employed to protect the wound edges from bacterial contamination and to minimize mechanical trauma. Several clinical trials have been performed to investigate their role in preventing SSIs with some success[132-134]. Plastic adhesive skin barriers used to prevent contamination are popular with some surgeons, but current data show no real impact on the rate of SSIs in general surgery[135]. The impact of surgical drains in the presence of synthetic mesh during AWR has been largely debated; however, a retrospective study provided evidence that their use does not increase SSI and may be protective against surgical site occurrences such as seroma[136]. Supplemental oxygenation in the perioperative period has been studied in colorectal surgery with two landmark studies showing a benefit by reducing SSIs[137,138]. A meta-analysis favored supplemental oxygen protocols in higher-risk populations[139]; however, there are no studies speci fic to AWR.

Another difficult topic in open abdominal surgery is pain control. Multimodal pain control with both pharmacological and non-pharmacological techniques are continuously being revisited to find the optimal regimen. Pain, and therefore pain control, is very subjective and has to be approached on an individual basis. Common pharmacological modalities include systemic opioids, local or regional blocks, central neuraxial infusions, acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gamma-aminobutyric acid analogs, and beta-blockers to name a few[140]. Several non-pharmacological techniques such as acupuncture,music therapy, and hypnosis have mixed evidence regarding efficacy. The role of preoperative anxiety on postoperative experience is often overlooked and may be an avenue for improvement. A meta-analysis of 54 studies showed an association between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain and analgesia requirements[141]. In addition to psychological preparation, proper education, and open communication of risks, bene fits, and expectations prior to surgery, music therapy may be an additional strategy to help ease anxiety[142]. Music likely shifts the patient attention and aids in cognitive coping. One study showed that patients report lower pain scores when exposed to music in the post-anesthesia care unit[143]and a metaanalysis showed music leads to reduced anxiety in mechanically ventilated patients, as evidenced by lower respiratory rates and systolic blood pressures, and may even reduce sedative and analgesia requirements[144].

CONCLUSION

As the incidence and complexity of VHR and AWR continues to rise, so does the importance of addressing all adjustable elements to achieve optimal outcomes. Identifying and intervening on these modifiable risk factors in the pre-, intra-, and immediately postoperative period is key to consistent success. It could certainly be argued that outcomes for these increasingly complex cases are less dependent on operative technique and more dependent on prehabilitation, addressing patient comorbidities preoperatively,adequate glucose control, focus on proper nutrition, and awareness of the microbiome.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Participated in accumulation of data, literature review, writing and editing the manuscript: Knapp N,Jedrzejewski B, Martindale R

The authors have had equal contributions to this article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Dr’s Knapp and Jedrzejewski have no con flicts of interest. Dr. Martindale has no direct con flicts of interest in this manuscript or subject matter but remains a consultant for Bard and Allergan.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors give consent for publication and release copyright issues.

Copyright

? The Author(s) 2020.

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2020年2期

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2020年2期

- Plastic and Aesthetic Research的其它文章

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS

- The bene fit of combined radiofrequency and uItrasound to enhance surgicaI and nonsurgicaI outcomes for the face and neck

- Comparison of adipose particIe size on autoIogous fat graft retention in a rodent modeI

- Indocyanine green lymphangiography-guided liposuction in breast cancer-related lymphedema treatment - patient selection and technique

- Mesh and plane selection: a summary of options and outcomes

- Expanding the top rungs of the extremity reconstructive ladder: targeted muscle reinnervation, osseointegration, and vascularized composite allotransplantation