Hepatitis C virus cure with direct acting antivirals: Clinical,economic, societal and patient value for China

Qing Xie, Jian-Wei Xuan, Hong Tang, Xiao-Guang Ye, Peng Xu, I-Heng Lee, Shan-Lian Hu

Qing Xie, Department of Infectious Diseases, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China

Jian-Wei Xuan, Health Economic Research Institute, School of Pharmacy, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510006, Guangdong Province, China

Hong Tang, Center of Infectious Diseases, West China Hospital of Sichuan University,Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

Xiao-Guang Ye, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510260, Guangdong Province, China

Peng Xu, Gilead Sciences Inc, Shanghai 200122, China

I-Heng Lee, Gilead Sciences Inc, Foster City, CA 94404, United States

Shan-Lian Hu, School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China

Shan-Lian Hu, Shanghai Health Development Research Center, Shanghai 200032, China

Abstract

Key words:Hepatitis C; Value of cure; Sustained virologic response; End stage liver disease; Prevention of transmission; Cost-effectiveness; Productivity; Societal value;Patient-reported outcomes

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, direct acting antiviral (DAA) treatments have replaced pegylatedinterferon (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) combination therapy (PR) as standard of care for patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) globally[1-3]. DAAs are associated with over 90% rates of sustained virologic response (SVR), fewer side effects, shorter treatment durations, and improved adherence compared to PR therapy[4].

Due to the substantial impact of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection globally on patients, their families, and public health systems, the World Health Organization(WHO) has set HCV elimination goals that include reduction of HCV incidence by 80% and HCV-related mortality by 65% by 2030[5]. As part of the strategy to achieve these goals, the WHO included DAA therapies in its 2017 edition of List of Essential Medicines[6]. Specifically, the latest (2018) WHO guidelines for HCV treatment make an updated recommendation of using pan-genotypic regimens for treating adult patients with chronic HCV infection[5]. Besides their proven high efficacy, pangenotypic regimens enable cost saving and care pathway simplification by eliminating the need for pre-treatment genotyping, potentially reducing loss to follow up among patients. Furthermore, the recommended pan-genotypic regimens, such as sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL), enable most HCV patients to be treated with simple treatment strategies regardless of patients’ prior treatment experience or cirrhosis status, with minimal need for regimen adjustment or on-treatment monitoring[5]. As reflected in this recommendation by the WHO, the value of highimpact, curative treatment for HCV infection is wide-ranging and goes beyond clinical efficacy.

In China, the number of individuals infected with HCV is estimated at 10 million,with a seroprevalence of anti-HCV antibodies of 0.6% among the general population[7,8]. In addition to the large and growing number of HCV-infected individuals, there have been a diversification of HCV genotypes (GTs) and a broadening of the age spectrum among Chinese HCV patients; GT1b or GT2a HCV patients historically infected through blood transfusion are aging, while an increasing number of younger patients are becoming infected with GT3a, 3b and 6a HCV through injection drug use[9-11]. The resulting healthcare expenditures, as well as reduction in quality of life and loss of work productivity among the Chinese CHCpopulation, are expected to have wide-ranging economic and societal implications.

In addition to the heavy disease burden, the management of the HCV epidemic has been compounded by a lag in adopting DAAs in China:up to early 2017, no DAA had been approved in China. To improve the availability of innovative treatments(including DAAs), China introduced policies that expedite the regulatory review process for drug registration. To date (March 2019), most of the mainstream DAA regimens used internationally have been approved in China, including daclatasvir plus asunaprevir (DCV + ASV), sofosbuvir plus simeprevir (SOF + SMV), SOF + DCV,the fixed-dose combination ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with or without dasabuvir (O/P/r ± D), SOF/VEL, ledipasvir (LDV)/SOF, and elbasvir/grazoprevir(EBR/GZR). Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB) and SOF/VEL/voxilaprevir (VOX)are also pending approval.

While the rapid improvement in DAA availability is encouraging, China is still far from universal adoption of DAA-based therapies. In an initial step to address the issue of drug accessibility, the Chinese government included SOF/VEL in the latest(October 2018) National Essential Drug List as the first and only DAA treatment[12].Nevertheless, DAAs are not covered by the National Medical Insurance scheme for reimbursement, and thus much less affordable compared with IFN-based therapies.As such, a considerable number of patients, such as those in rural and less-developed areas and those with limited financial means, would still have to resort to IFN-based therapies.

In light of how IFN-free DAA regimens have revolutionized treatment for HCV-infected patients, many countries are now aiming for elimination of the disease[13]; the introduction of DAA regimens in China therefore, also provides the opportunity for potential hepatitis C elimination. In the 2017-2020 National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan, the Chinese government emphasized the use of more efficacious treatment as part of the strategy to reduce the spread of HCV[14]. The overarching Healthy China 2030 Plan also showed the Chinese government’s commitment to establish public health as the foundation for future economic and societal development[15]. In line with the country’s strategic approach to healthcare and hepatitis management, this article aims to comprehensively evaluate the value of curative HCV therapies in the dimensions of clinical, patient, economic and societal benefits, in the hope of providing useful references for various stakeholders and policy makers in China.Where possible, data from China have been used, supplemented with data from other Asian countries and from around the world when Chinese data are unavailable.

CLINICAL BENEFITS OF CURING HCV INFECTION

Impact of HCV infection and treatment on the liver

The principal impact of HCV is on the liver, the predominant site of HCV replication.While initial HCV infection resolves spontaneously in around 15%-25% of cases, the majority of patients will develop CHC[16]. The long-term outcomes of the liver inflammation caused by HCV infection include the development of fibrosis,compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and end-stage liver disease (ESLD)[16]. Progression of CHC typically occurs over many years; it is estimated that 10%-20% of patients will develop cirrhosis and the annual risk of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is approximately 1%-4%[16]. If left untreated,CHC patients would progress to more advanced disease stages, which in turn are associated with accelerated disease progression, elevated risks of developing HCC,and consequently lower survival rates[4]. A long-term retrospective cohort study in Japanese CHC patients showed that untreated F0/F1 patients have a 0.5% annual risk for HCC development, while this increased to 7.9% in F4 patients[17]. A systematic review of CHC patients in Asia, including China, reported that the 5-year survival for cirrhotic CHC patients was 73.8%, but falls to 39.2% following progression to ESLD,wherein liver transplantation is required[18].

China has an estimated annual incidence of 53593 cases (95%CI:16144-92466) of HCV-related HCC[19], with > 93000 cases of HCV-related liver cancer deaths recorded in 2005[20]. The majority of Chinese HCV patients were infected through blood transfusion before 1993-1996, in whom age and duration of infection are significant risk factors for disease progression[21]. As these patients grow older and enter their third or fourth decade of infection, the occurrence of decompensated cirrhosis (DCC),HCC and ELSD will rise. On the other hand, China has seen a recent increase in younger patients with GT3 HCV[10,22]. A study in Shanghai reported evidence that GT3 patients undergo faster disease progression, with GT3 patients < 50 years of age showing significantly more advanced fibrosis than their non-GT3 counterparts[22]. If left untreated, considerable numbers of liver sequelae will develop in these youngerGT3 patients in future.

Antiviral treatment and resultant SVR improve the long-term clinical outcome of HCV patients[23-28]. The beneficial effects of IFN-based treatment and SVR on reducing cirrhosis progression, HCC, and mortality have been well documented, and this is reflected by the recently published results from two large-scale studies in Asia and two Chinese cohort studies[29-32]. Similar clinical benefits have been observed with SVR to DAA-based treatment. In a large-scale, retrospective study in Japan, GT1 HCV patients who achieved SVR to all-oral DAA regimens had a lower cumulative incidence of HCC than non-SVR patients at 2 years post-treatment (Figure 1)[27].Furthermore, a recent Chinese prospective study in DAA-treated and case-matched PR-treated patients showed no difference in the risk of developing HCC post-SVR[33].DAA treatment was also associated with a 32% reduction in liver-related mortality relative to no treatment[25], and DAA-mediated SVR conferred reductions in all-cause mortality relative to non-SVR in patients with or without advanced liver disease by 79% and 56%, respectively[23,24].

A meta-analysis of 31 studies in predominantly GT1 HCV-infected patients(including Asian patients) showed that achieving SVR conferred survival benefit irrespective of patients’ clinical characteristics, with difficult-to-treat populations such as cirrhotic patients experiencing the largest extent of reduction in 5-year mortality compared to no SVR[34]. Nonetheless, the hepatic and survival benefits of achieving SVR are maximized by treating patients in earlier disease stages[31,35]. For instance, for Asian cirrhotic patients who achieved SVR, despite a reduction in cumulative risk of HCC by 25.5 percentage points relative to cirrhotic patients without SVR, the associated risk of HCC was still higher than non-cirrhotic patients with SVR (0.54vs0.37)[31]. Thus, the WHO guidelines recommend treating all HCV-infected patients without disease stage-based restriction or prioritization, with an emphasis on minimizing treatment delay after diagnosis[5].

Although SVR to either IFN- or DAA-based treatment reduces liver disease progression, the impact of IFN-based treatment would be limited due to low SVR rates (40%-75%)[4,36]. In a meta-analysis of 12 studies involving 25497 CHC patients on IFN-based therapy, although SVR achievement led to a 76% reduction in HCC risk,only 36% of patients achieved SVR[37]. PR treatment also has numerous contraindications and side effects, such as RBV-induced hemolytic anemia and various neuropsychiatric, autoimmune, ischemic, and infectious disorders that may be caused or aggravated by IFN[38,39]. In the nationwide CCgenos study, 56.7% of untreated Chinese HCV patients were IFN-ineligible[40]. In contrast, DAA regimens confer high real-world SVR rates of 90%-100%, and extend HCV cure to patient populations that could not be effectively treated in the PR era, such as patients with DCC and/or liver transplant, and patients with concomitant renal impairment or psychiatric disorders (although the eligible patient populations and efficacy profiles do differ among DAA regimens)[41]. As such, DAAs would have a greater impact than IFN-based therapy in significantly reducing HCV-related liver sequelae and deaths at the population level[42]. Evidence for such populational benefits associated with expanded DAA use is emerging internationally, and various countries are promoting the use and reimbursement of DAAs as a key strategy towards the goal of HCV elimination. For example, in England, a national 40% scale-up of DAA provision in 2015 was followed by reductions in the incidence of HCV-related cirrhosis (42%), liver transplantations (32%), and deaths (8%)[43]. In 2018, Canada is progressively removing the eligibility criterion of F2+ fibrosis for DAA reimbursement[44].

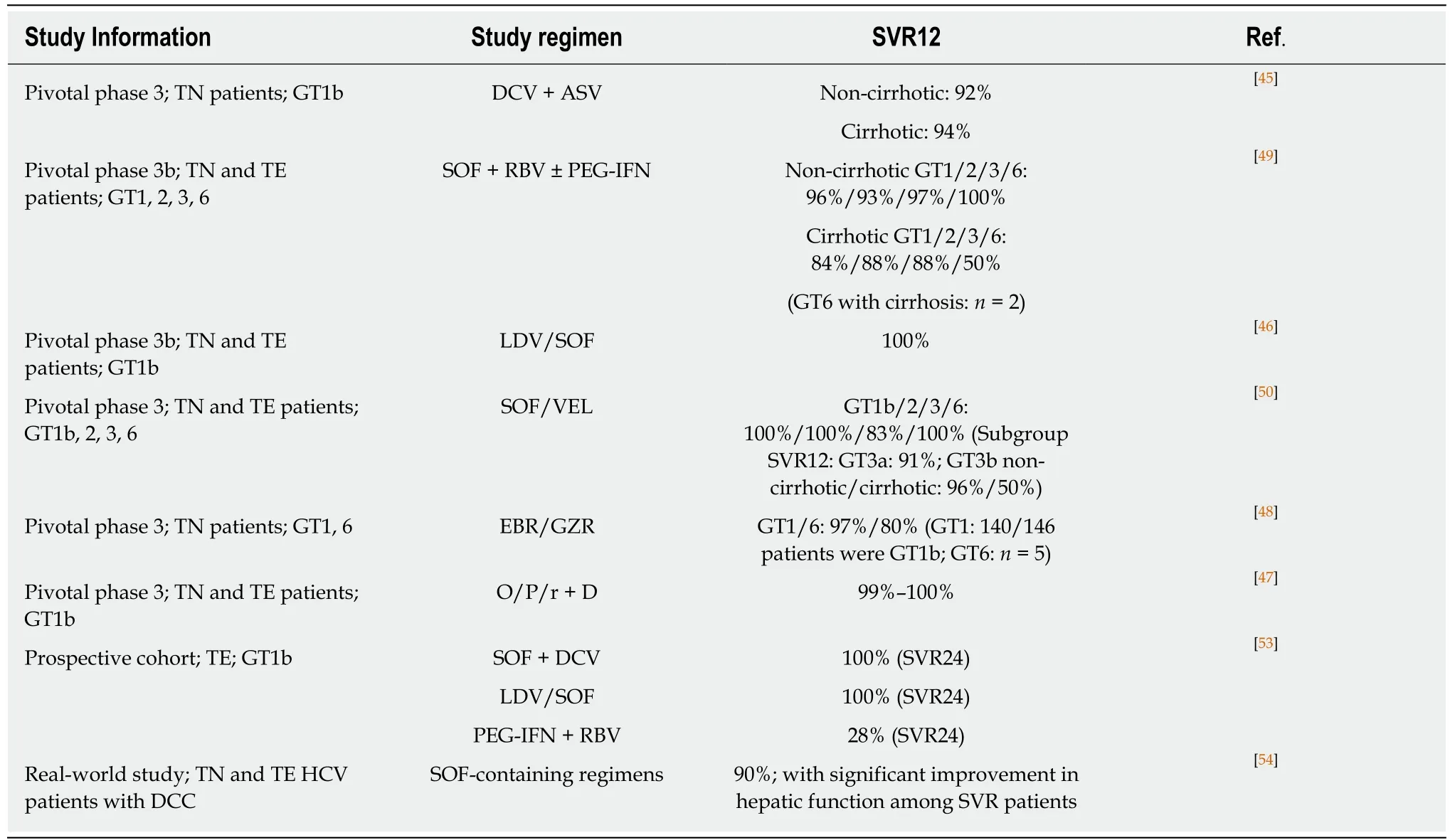

In China, DAAs achieved high SVR rates in pivotal clinical studies (Table 1).Evaluated genotype-specific regimens (DCV + ASV, LDV/SOF, EBR/GZR, and O/P/r + D) all achieved SVR12 rates ≥ 92% in GT1 or GT1b patients[45-48]. Pangenotypic regimens evaluated in clinical studies included SOF + RBV ± PEG-IFN and SOF/VEL. For SOF + RBV ± PEG-IFN, cirrhotic patients achieved lower SVR12 rates than non-cirrhotic patients (Table 1)[49]. For SOF/VEL, the only patient population with an SVR12 rate below 90% was GT3b cirrhotic patients (Table 1), who also exhibited a high prevalence of baseline A30K + L31M substitutions[50,51]. Due to the short period of DAA application, real-world efficacy data in China are only emerging.Majority of the early real-world studies focused on SOF-based regimens (reviewed by Anet al[52]); two examples are shown in Table 1, where SOF-based regimens demonstrated high efficacy in difficult-to-treat patients[53,54].

Figure 1 Viral elimination by all-oral direct acting antiviral treatment reduces rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus-infected patients.

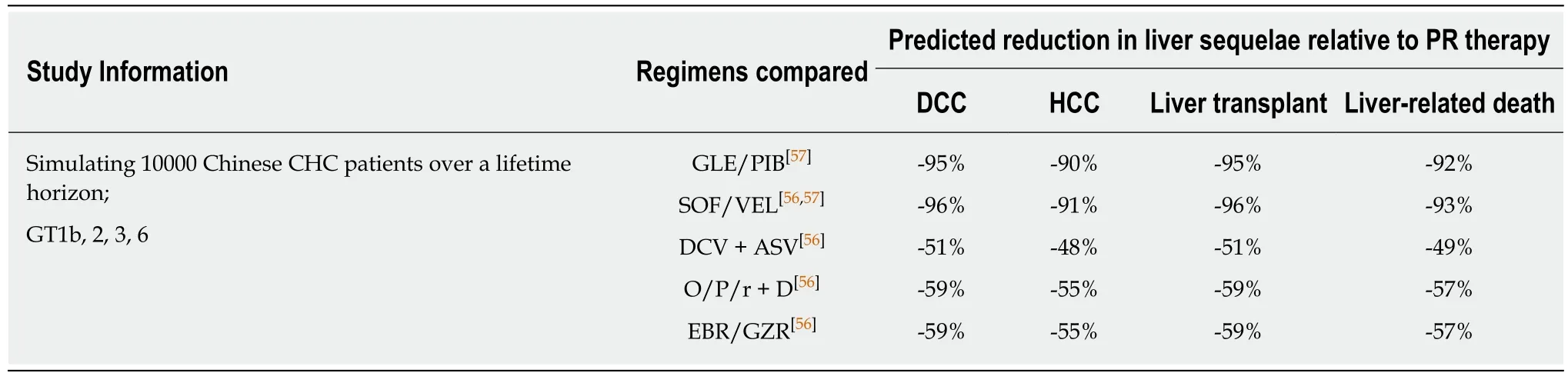

Using China-specific SVR data where available, modeling studies predicted that compared to PR, DAA treatment would markedly reduce the HCV-associated longterm disease burden and mortality. A study simulating the national-level disease burden of CHC in China predicted that with no treatment, the prevalence of HCV would continue increasing and reach 28.1 million in 2050, with 2.4 million liverrelated deaths, mostly attributable to DCC and HCC[55]. The model predicted that using PR therapy would not be able to revert the trend of increase in HCV prevalence.In contrast, universal adoption of DAAs from 2021 onward would significantly reduce the HCV prevalence. Furthermore, compared to using PR therapy, universal DAA adoption would reduce the cases of incident DCC, HCC, liver transplants, and liver-related deaths by 61%, 45%, 50%, and 61%, respectively[55]. Similarly, simulations of 10000 Chinese CHC patients over a lifetime horizon predicted that various DAA regimens would significantly reduce the incidence of HCV-related liver sequelae and mortality compared to PR therapy[56,57]. These simulations took into consideration the composition of different HCV genotypes, treatment history and cirrhotic status of the patient population, thus, pan-genotypic regimens (SOF/VEL and GLE/PIB) were predicted to achieve higher overall SVR rates and greater reduction in disease progression than genotype-specific DAA regimens (Table 2)[56,57].

Extrahepatic manifestations

Besides the direct impact on the liver, HCV-infected patients may experience liverunrelated symptoms that, depending on epidemiological evidence, are considered extrahepatic manifestations (EHMs) associated or possibly associated with HCV infection[58,59]. The most documented EHMs are mixed cryoglobulinemia/cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A diverse range of other conditions also occur at higher prevalence in HCV-infected patients, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, renal diseases, fatigue, cardiovascular disease, and lichen planus (LP), to name a few[58]. EHMs can occur in > 70% of CHC patients, and can be present before advancement into ESLD[59]. Underlining the impact of EHMs on HCV patients, a Taiwanese study reported a cumulative 18-year EHM-related mortality of 19.8% in patients with chronic HCV infection, much higher than the non-liver-related mortality in those without HCV infection (12.2%)[60]. Published studies on EHMs in China are few, and there is currently a lack of clinical data on the prevalence and management of EHMs among Chinese patients[61].

A recent meta-analysis investigated the extrahepatic benefit of antiviral treatment and SVR in HCV patients[62]. Achieving SVR significantly reduced extrahepatic mortality (vsno SVR, OR 0.44, 95%CI:0.28-0.67), was associated with improvements in cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases, and reduced the incidence of insulin resistance and diabetes[62]. Concordantly, IFN-based treatmentinduced favorable immunologic response in Chinese cryoglobulinemic patients with HCV infection, and IFN-based SVR reduced the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus among Japanese HCV patients[63,64]. Of note, IFN-based treatment may exacerbate symptoms of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, likely due to the immune-stimulatory effects of IFN[65,66]. IFN also induces lichenoid inflammation, and is thus contraindicated to LP[66].

Table 1 Clinical efficacy of direct acting antiviral in major empirical studies in China

Emerging data support the extrahepatic benefit of successful DAA treatment for HCV patients[67]. In two prospective studies on patients with HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemia, SOF-based regimens conferred 100% SVR rates and clinical improvement or resolution of mixed cryoglobulinemia-associated vasculitis[68,69]. In a retrospective study on 46 CHC patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, DAA treatment (mostly SOF-based) achieved an SVR rate of 98%, together with a lymphoproliferative disease response rate of 67% and survival benefit[70]. In a prospective Japanese study, 7 patients with HCV-related oral LP all achieved resolution or improvement of oral LP lesions and cutaneous LP upon DAA-based SVR[71].

In short, existing data on DAAs are in line with data from the IFN era, showing that SVR attainment aids the amelioration of HCV-associated EHMs. While further research is needed on the effect of DAAs on EHMs, the higher virologic efficacy,fewer side effects, and shorter treatment durations of DAAs would likely amplify the health benefit of reducing disease burden associated with extrahepatic complications[67].

Prevention of HCV transmission

Effective treatment of diagnosed patients is an integral part of a comprehensive approach to preventing HCV transmission, which also requires public education to raise disease awareness and efficient screening and linkage to care[72]. HCV prevention strategies also need to be aligned with the predominant mode of transmission[72].

There is substantial regional variation in risk factors for HCV infection in China. In regions outside Southern China, blood transfusion is the major route of HCV transmission, accounting for 57.5%-69.3% of existing HCV-infected patients. Infection through surgery or dental treatment is more common in Northern China than in other areas, whereas HCV transmissionviahigh-risk behavior such as intravenous drug abuse is more prevalent in Southern and Western China[10]. Within each broad geographical region, the modes of HCV transmission may also show urban-ruraldifferences. Current HCV prevention measures in China include screening of all blood donors, as well as harm reduction services for high-risk groups like injection drug users (IDUs)[3,73].

Table 2 Model predicted long-term clinical outcomes of using direct acting antivirals in China

In addition to existing prevention measures, treating HCV infection with highly effective therapy can function as a prevention strategy [treatment as prevention, TasP]by essentially removing individuals in key populations from the pool of transmitters.Numerous TasP modelling studies predicted that HCV treatment of sufficient effectiveness and accessibility would help reduce the incidence and chronic prevalence of HCV infection among IDUs, prisoners, and men who have sex with men (MSM)[74]. For example, in Melbourne, with HCV prevalence among IDUs at 50%,increasing uptake of DAA treatment to 40 per 1000 IDUs annually is expected to halve HCV prevalence rates within 15 years; while scaling up treatment to 54 per 1000 IDUs annually could cut prevalence rates by as much as 75%[75].

Empirical evidence verifying these positive projections are currently scarce, but some real-world programs are underway, reflecting confidence in the potential of HCV TasP. In Australia, a world-first HCV surveillance and treatment program assessing the use of SOF/VEL for HCV TasP in prisons is expected to be completed by 2019[76]. Notably, high real-world efficacy of SOF/VEL has been demonstrated among HCV-infected, treatment-adherent IDUs with recent injection, lending confidence to the notion that treatment scale-up and adherence management would effectively control HCV transmission among IDUs[77]. In 2016, Iceland (with a population of 340000) launched the nationwide program of Treatment as Prevention for Hepatitis C(“TraP Hep C”), offering universal access to DAAs for HCV-infected patients, with an emphasis on treating high-risk transmitters such as IDUs[78]. International guidelines also recognized the benefit of reduced transmission with successful HCV treatment[1,2,79]. Guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the WHO further highlighted that HCV screening and treatment should be prioritized in individuals at high-risk of transmitting HCV such as IDUs[2,79].

With the regional variations in HCV epidemiology in China, tailored strategies at the provincial or even district/city level will be necessary for HCV prevention and control[80]. Suitable measures targeting specific modes of transmission will facilitate HCV ‘micro-elimination’ within certain populations:such is the strategy adopted by many countries for HCV elimination, and can form part of a realistic approach in China towards accomplishing the goals in the National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan[14].In particular, China has a documented IDU population of 2.95 million, among whom the estimated HCV prevalence is 50.4%[81,82]. In this key population, efficacious HCV treatments, together with targeted education campaigns, continued harm reduction measures, and efficient diagnosis and linkage to care, would be required to reduce the prevalence and transmission of HCV[14,15].

ECONOMIC AND SOCIETAL VALUE OF CURING HCV INFECTION

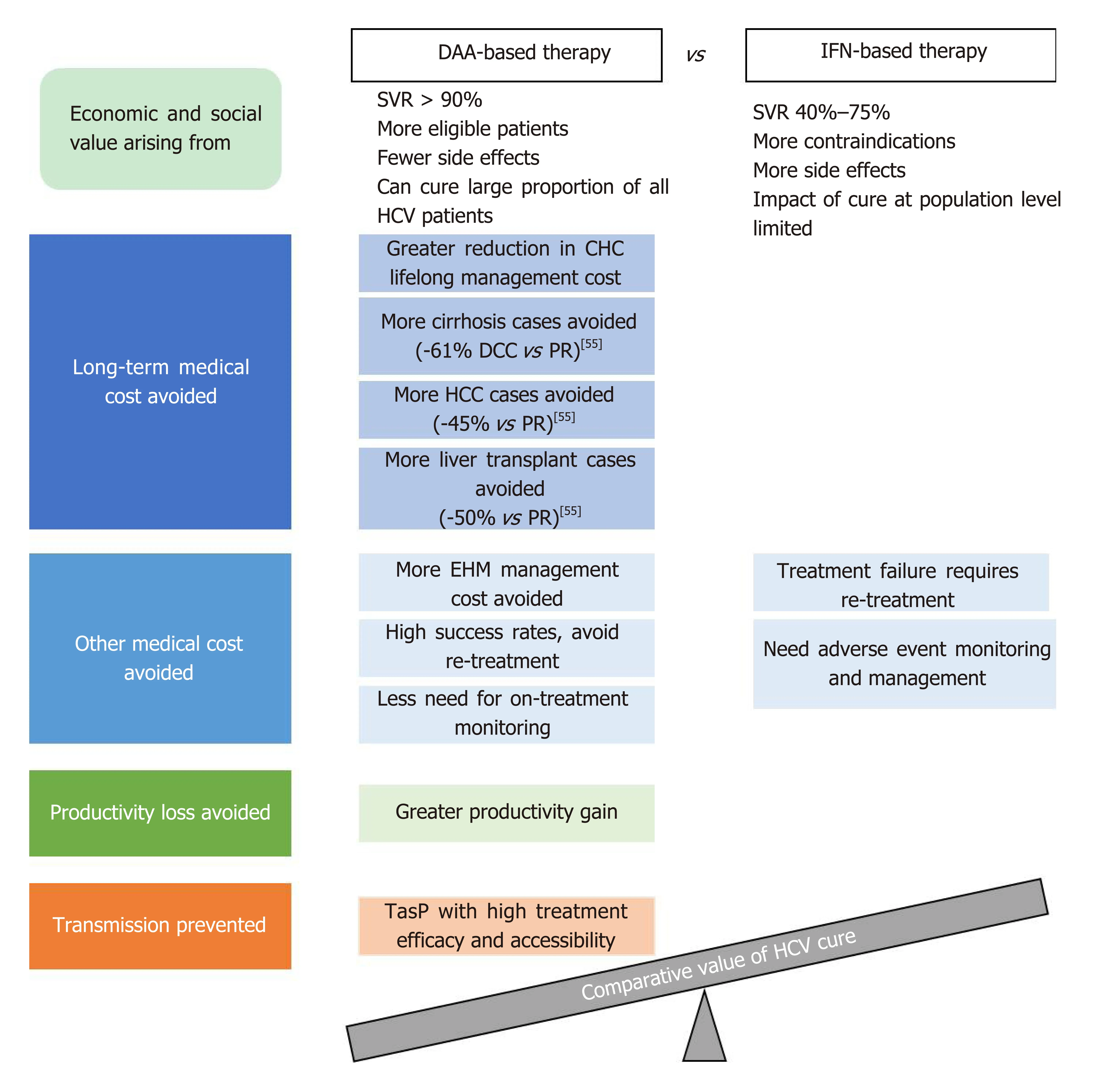

As illustrated in the WHO 2018 guidelines, HCV control strategies are formulated based on not only the clinical efficacy of treatment options, but also their costeffectiveness and the broader value and benefits they bring to patients and society[5].Curing HCV infection can generate economic and societal value on many fronts,depending on the efficacy, safety, and other characteristics of the treatment optionsused. Figure 2 provides an overview of the main factors contributing to the economic and societal value of DAA- and IFN-based HCV treatment. It is challenging for any existing value assessment model to incorporate all the factors shown in Figure 2; the following sections seek to provide relevant information in these areas to enable a holistic discussion on the value of curing HCV infection.

Significance of economic and societal burden of CHC

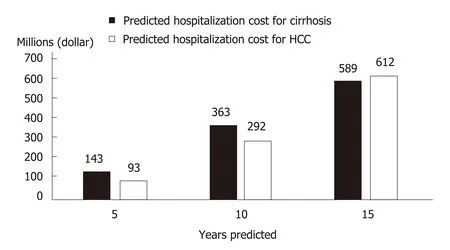

Costing studies on the management of CHC generally found that more advanced disease stages are associated with higher medical costs, which constitute a financial burden to patients, healthcare systems, and society[83,84]. Within the CHC population in China, nearly a quarter are hospitalized at least once per year with a median duration of 2 wk[85]. Since later disease stages are costlier, treatment delay would lead to increased future costs associated with disease progression. A modelling study in China captured such a scenario and highlighted the impact of treatment delay on younger patients who, with a longer life expectancy, would incur higher life-time disease management costs than older patients with a similar initial disease state[86].With a 3-year treatment deferment, the projected cost for managing future ESLD in non-cirrhotic patients aged 40 increased from RMB 4407359 to RMB 7997253, while the corresponding cost increment for non-cirrhotic patients aged 70 was from RMB 2091499 to RMB 5565547[86]. At the population level, more cases of cirrhosis and HCC would occur as CHC patients age, leading to higher healthcare costs in the future[87].China faces both an increasing population of younger, incident patients and an aging population of prevalent patients[9-11]. Without effective treatment, it was predicted that over the next 15 years, 420000 new cases of HCV-related cirrhosis and 254000 new cases of HCV-related HCC would occur, leading to future treatment costs of 589 million and 611 million dollars respectively (Figure 3)[8,88].

Besides the cost of managing liver-related morbidity of CHC, economic burden also arises from HCV-associated EHMs. In a meta-analysis of 102 studies conducted between 1996 and 2014, the annual medical costs of managing EHMs, in 2014 dollars,amounted to approximately $1.5 billion[89]. Therefore, curing HCV would also be expected to reduce the cost of managing EHMs as well as preventing expensive longterm liver morbidities.

In addition to direct costs related to CHC management, the growing involvement of younger, work age HCV patients in China also poses a broader societal issue[11,84].HCV patients may suffer from fatigue, low energy, and impaired general health; the resultant impairment of work productivity would have repercussions on the financial and psychological well-being of the HCV-infected young individuals and their families[89]. Employers of HCV-infected individuals would also face reduced output and earnings due to loss of worker productivity, in the forms of absenteeism and presenteeism[90]. Based on a modelling study in HCV GT1-infected Chinese patients,the monetized productivity losses resulting from non-treatment amount to RMB 37.78 billion per year[91].

By effectively curing HCV infection, HCV therapeutic innovation would help alleviate the heavy economic and societal burdens caused by CHC, yet such innovation would require upfront investments. To determine which treatment strategy offers the best “value for money” (cost-effectiveness), health economic models are used to weigh the costs of different HCV treatment options against their long-term cost savings.

Cost-effectiveness considerations in HCV treatment

Health economic analysis in HCV predominantly focuses on the direct medical costs of managing HCV. As discussed previously, more advanced disease stages are associated with higher medical costs, and patients who achieve SVR have lower probabilities of progressing to the later, costlier disease stages. Thus, in theory, more effective HCV treatments should save more on long-term medical costs by avoiding disease progression in more patients. Health economic models evaluate the costs thus saved, along with the benefits of life extension and improved quality of life, against the upfront investments needed for implementing certain treatment methods.Currently, health economic research on HCV treatment in China is expanding rapidly.Emerging health economic analysis results from China will be introduced, together with analyses from countries with more experience using DAAs, to evaluate the potential costs and benefits associated with upfront investments in HCV treatment innovation.

Figure 2 Main factors contributing to the comparative economic and societal value of direct acting antiviraland interferon-based treatment for hepatitis C virus infection.

In health economic analysis, the gain in patients’ quantity and quality of life achieved using a certain treatment is measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs),and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) measures the cost needed to achieve a unit gain in QALYs; if the ICER of a treatment is below the willingness-topay threshold, it is considered cost-effective. In a systematic review of health economic studies in the United States, Europe, and Australia, second-generation DAAs, compared to first-generation DAAs, PR therapy, or non-treatment, were shown to be either cost-saving or cost-effective in the majority of the analyses as judged by the ICERs calculated[92]. Furthermore, a modelling analysis in the United States compared various second-generation DAA regimens for treating GT1 patients;the results predicted that a treatment strategy of 8-wk LDV/SOF for GT1, treatmentna?ve (TN), non-cirrhotic patients with a viral load less than 6 million copies, and SOF/VEL for all other GT1 patients was the most cost-effective strategy, resulting in 35% fewer cases of advanced liver disease events, with up to 57% reduction in cost per SVR relative to the other comparator regimens[93].

Moving beyond the conventional methodology using ICERs, recent health economic studies devised other indicators to better elucidate the economic value of HCV therapies, by monetizing QALYs gained so that they can be directly compared against the costs of treatment. A United States economic model study in HCV GT1 patients predicted that all-oral therapies, in relation to PR therapy, improved health by 1.622 QALYs per patient, thereby leading to an overall decrease of 32730-500599 dollar in quality-adjusted cost of care, which was defined as the increase in the price of treatment minus the increase in the value of the patient’s expected QALYs when valued at 50000-300000 dollar per QALY[94].

Figure 3 Projected chronic hepatitis C-related medical costs in China in the absence of effective hepatitis C virus treatment.

Unlike the abovementioned counties and regions, China is still early in its transition from IFN to DAA-based regimens. Health economic studies in China are fast emerging, mostly focused on comparing DAA regimens with IFN-based treatments, reflecting an acute need for cost-effectiveness data to inform potential health technology assessment decisions at this stage. The DCV + ASV regimen was predicted to be more or comparably cost-effective relative to IFN- or RBV-containing regimens in GT1b patients in two analyses[95,96]; an SMV-containing regimen was also predicted to be more cost-effective than PEG-IFN-based therapy in GT1 patients[97].Another study predicted that compared to PR, O/P/r + D would be cost-saving in GT1b patients, and SOF + RBV cost-effective in GT2/3 patients and cost-saving in GT6 patients, respectively[98]. One of the aforementioned studies simulating 10000 Chinese CHC patients with various HCV genotypes predicted that all the thenavailable second-generation DAA regimens (DCV + ASV, O/P/r + D, SOF/VEL, and EBR/GZR) would have cost-effectiveness advantages over PR therapy, with the pangenotypic SOF/VEL conferring the greatest gain in QALYs (by 17%) and reduction in lifetime cost (by 49%) relative to PR[56]. Among genotype-specific DAA regimens, one study predicted that for GT1b Chinese patients stratified by cirrhosis status and treatment history, EBR/GZR would be more cost-effective than DCV + ASV[99].

Cost-effectiveness analyses derived from a real-world prospective cohort predicted that for Chinese GT1b cirrhotic, PR-experienced patients, 12-wk LDV/SOF and 12-wk SOF+DCV would be cost-saving and cost-effective, respectively, compared to repeated PR treatment for 72 wk[53]. Analyzing real-world data from the PR era, a Taiwanese study reported that the costs per SVR for PR treatment were the highest in GT1/6 patients co-infected with HIV, due to low SVR rates in these populations;EBR/GZR, though more expensive than PR, would theoretically offer similar costs per SVR thanks to significantly higher SVR rates[100]. These two studies highlight the value of DAAs for traditional difficult-to-treat patient populations, and illustrate how the benefit of short treatment durations and high efficacy can offset the impact of high drug price for DAAs to maintain favorable cost-effectiveness profiles. Furthermore,two budget impact studies, from Hong Kong and three cities in Mainland China respectively, both predicted that although subsidizing DAAs would incur additional short-term drug costs, the resultant gain in patients’ health benefit and the avoidance of long-term disease management costs would be desirable[101,102].

Besides the factor of avoiding disease progression-associated long-term costs of HCV sequalae, health economic models take into account additional factors contributing to cost of care[94]. For PR therapy, such additional factors include the costs of monitoring and managing adverse events, and of re-treating patients who failed or discontinued the treatment[4]. With a high incidence of adverse events and the need for frequent monitoring, PR treatment can negatively impact patients’ quality of life(which will be discussed in a later section), resulting in lower QALY gains compared to DAA treatment. DAA therapy with its better safety and efficacy profiles can avoid such costs altogether if used as a first-line treatment. Indeed, one study predicted that for treatment-na?ve Chinese GT1 patients, treatment with all-oral DAA regimens,either immediate or with a 1-year delay, would generate positive net monetary benefits of 6832 dollar and 3115 dollar, respectively, compared to immediate PEGIFN-based treatment, at a willingness-to-pay threshold of 21209 dollar per SVR[103]. On the other hand, certain DAA therapies may incur costs associated with genotype/subtype or baseline resistance testing; such costs could be avoided with the application of pan-genotypic DAA regimens and regimens with high resistance barrier. Further studies would be required to fully elucidate the costs and savings associated with different DAA regimens in this respect.

In summary, modelling analyses conducted in the United States, Europe, and high-income Asian countries thus far have suggested that DAAs are likely to be cost effective compared to conventional IFN-based therapies; emerging health economic evidence in China is in line with these international findings. DAA regimens are easy to use, of shorter treatment duration, and requiring less monitoring than IFN-based therapy; the management cost thus saved, together with the long-term saving in CHC-related medical cost, would likely outweigh the upfront investment in DAAs.This is consistent with the WHO’s recommendation, whereby treatment regimens with better tolerability and safety profiles that simplify the care pathway would be preferred by patients and policy makers, which may also facilitate care coverage expansion and equity in treatment access[5].

Societal value of HCV treatment

The health economic analyses discussed above focus mostly on medical costs and do not capture the societal value of curing HCV. As will be discussed here, the additional potential benefits of curing HCV, such as improved productivity in Chinese workers and reduced HCV transmission, would further offset the upfront investment in HCV treatment.

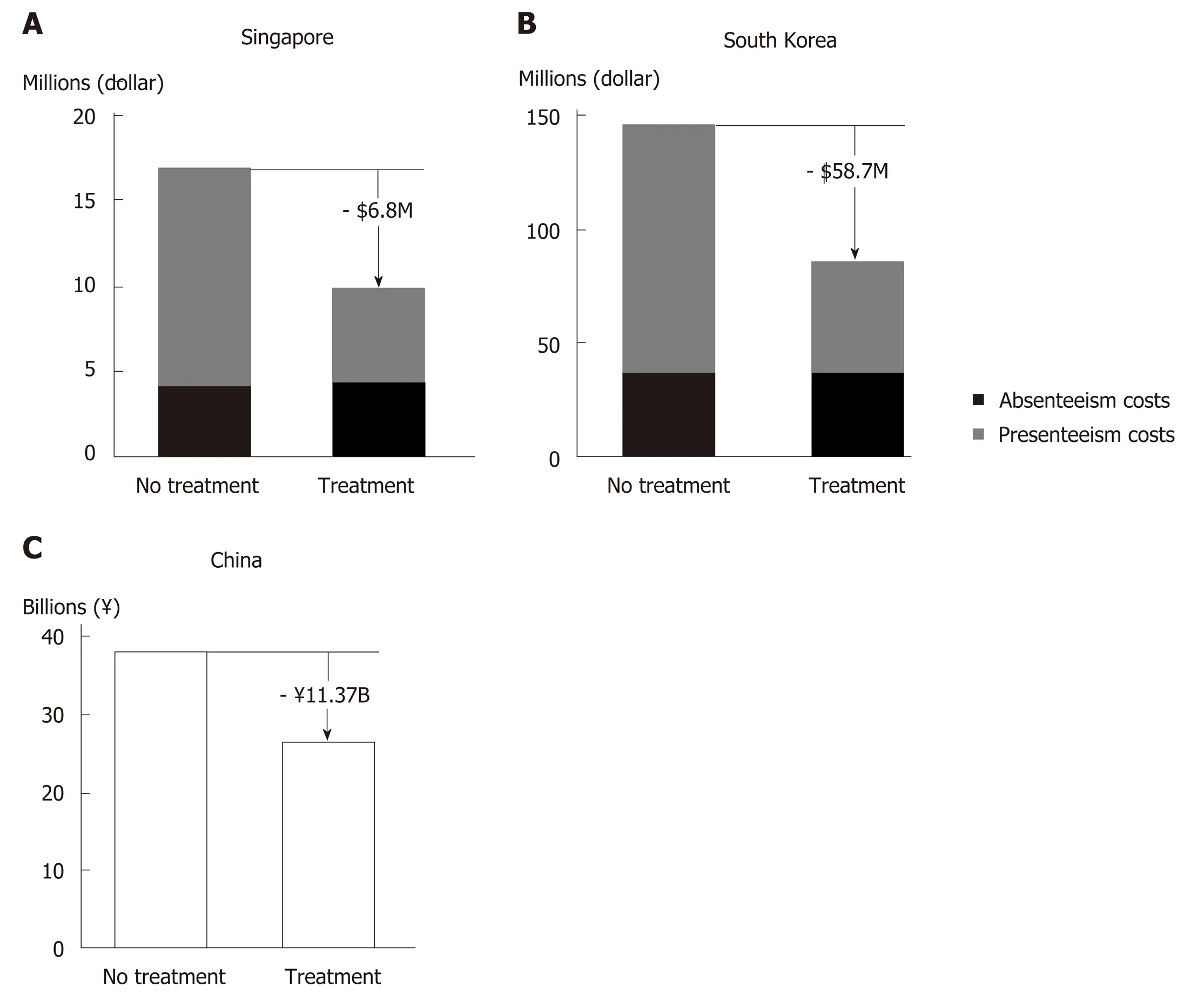

Reduced productivity impairment has been predicted in Asian CHC patients with successful HCV treatment (Figure 4)[104]. Hence, introduction of therapies with high SVR rates in China would likely improve work productivity among Chinese CHC patients, and in turn ameliorate the financial burden of HCV infection at an individual and family level. The resulting economic stability within a family unit owing to attainment of HCV cure could be of great benefit to China’s societal fabric.

From the employer standpoint, improved worker productivity increases revenue generation[104]. A modelling study in HCV GT1-infected Chinese patients showed that treatment with SOF/VEL would generate annual productivity gains equivalent to RMB 11.37 billion, mainly driven by reduced presenteeism (Figure 4C)[91]. The consideration of presenteeism in addition to absenteeism in the model is a more accurate representation of the actual reduction in productivity impairment in the context of Asian culture that values stoic industriousness.

Besides work productivity, another aspect typically not captured in health economic analyses is the benefits of stopping onward transmission through effective HCV treatment in key populations. Based on projections from a modelling study in the UK, at 10%-100% treatment uptake among IDUs and cost of GBP 20000 per QALY, reduced HCV transmission with DAA therapy led to an additional net monetary benefit of GBP 24304-90559 per patient[105]. One modelling study in China estimated the cost associated with HCV management in IDUs at RMB 21900 per patient per year[82]. With a predicted 20-year cumulative HCV incidence in 48.28% of IDUs, effective TasP in IDUs in China would conceivably translate into considerable societal and economic values[82].

In summary, effective HCV treatment can benefit society through improving working productivity and reducing HCV transmission. As reflected in the modelling studies above, such benefits would translate into tremendous value in addition to the economic benefit of reducing medical costs.

PATIENTS’ EXPERIENCE WITH HCV TREATMENT

While SVR is the main clinical indicator of HCV treatment success, a patient’s overall experience with the disease and the treatment process can be captured by patient reported outcomes (PROs). PROs are directly reported by patients without interpretation by HCPs and are used as proxy indicators of patients’ overall wellbeing. As mentioned earlier, HCV patients often experience debilitating fatigue and impairment to work productivity and non-work activities[89]. HCV infection also causes neuropsychiatric manifestations such as “brain fog”, whereby patients suffer from difficulty in attention and memory, alongside other cognitive impairments[106].Clearly, HCV infection and its systemic manifestations negatively impact patients’health-related quality of life (HRQoL)[89,106]. As such, the importance of assessing PROs in HCV management has gained considerable attention internationally over the past decade[107,108]. PRO data can also contribute to informing healthcare policy making[109].Patients’ demographic characteristics and cultural background may influence how they perceive and report their conditions; thus country-specific PRO data would be important for an accurate understanding of the impact of the disease[4].

Multiple PRO instruments can be used to assess HCV patients’ HRQoL, which typically assess patients’ conditions in several aspects, or domains; the outcomes are reported using domain and summary scores (Supplementary Table 1).

HCV disease burden in China as reflected in PRO data

Figure 4 Predicted reduction in hepatitis C virus-related productivity loss with direct acting antiviral treatment.

HCV infection negatively impacts patients’ health and quality of life throughout the disease stages. Evidence indicates that there is already measurable damage to HRQoL in asymptomatic or undiagnosed patients with HCV infection[110]. PRO measurements deteriorate further as the disease progresses to more severe and advanced stages, as reported by studies from Thailand and Japan[111,112].

In China, studies on PROs in HCV patients have been scarce. Nevertheless, existing data showed that impairment in quality of life contributes to the disease burden of HCV infection. As part of the nationwide CCgenos study, cross-sectional data collected in 2011 from 997 untreated patients with chronic HCV infection reported a mean Euro-QoL 5 Dimensions descriptive score of 0.780/1[113]. The percentage of patients reporting moderate or severe problems was about 34% for both the domains of pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, and 7%-8% for the domains of mobility and usual activities[113]. Similarly, results from local studies in rural Liaoning and Beijing using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) and/or the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) scales revealed low quality of life among CHC patients[114,115].In a community-based survey of CHB and CHC patients in Shanghai using the Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Disease-Chronic Hepatitis and the Family Burden Interview Schedule, multivariable analyses identified HCV infection and elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level as direct risk factors negatively impacting both the patients’ quality of life and the burden on their caregivers[116].Clearly, the wellbeing and quality of life of Chinese HCV patients and caregivers are adversely affected by the disease, calling for closer attention to patient experience in HCV management.

Impact of different HCV treatment regimens on patient experience

To understand how treating and curing HCV infection can affect patients’ experience and wellbeing, PROs are typically measured pre-treatment, at different time points during treatment, at the end of treatment (EoT), and 12 or 24 wk post-treatment.

Impact of PR therapy on PROs:PR therapy is known to cause on-treatmentdeterioration in PROs due to side effects of and intolerance to the regime. A crosssectional study in Taiwan reported that CHC patients on PR treatment (n= 108)scored significantly lower than untreated CHC patients on some of the SF-36 and CLDQ scales[117]. Illustrating the on-treatment PRO impairment more clearly, another Taiwanese study involving 47 PR-treated CHC patients showed that by treatment week 12, the patients’ mean scores for all 8 SF-36 domains decreased significantly from baseline[118].

Upon PR treatment completion, PRO parameters would return to pre-treatment levels, or improve further upon treatment success. In the afore-mentioned study of 47 PR-treated patients, the SF-36 domain scores of those who achieved SVR (n= 21)improved significantly over baseline by week 24 post-treatment. In contrast, the domain scores of non-SVR patients (n= 26), though recovered from treatment week 12 to pre-treatment level by EoT, did not improve further post-treatment[118]. A study in Guangzhou involving 72 CHC patients treated with PR reported that by EoT and similarly at week 24 post-treatment, patients’ quality of life as measured by the Generic Quality of Life Inventory-74 questionnaire improved significantly over baseline, being significantly better than that of 30 untreated CHC patients at the same timepoints. This study did not report on-treatment QoL measurements or patients’SVR status[119].

Impact of DAA regimens on PROs:Throughout the development of DAAs, various combination therapies have been studied and used, including DAA + IFN + RBV,DAA + RBV, and DAA-only regimens. For SOF-based regimens, PRO data collected from pivotal clinical studies in Western countries, Japan and other Asian regions(China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam) consistently demonstrated that for all three types of DAA combination therapy, achieving SVR12 was associated with post-treatment PRO improvement, although compared to PR-containing or IFN-free, RBV-containing regimens, DAA-only treatment offered better on-treatment patient experience[120-124].

Specifically for HCV patients in China, pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies on SOF-based regimens showed that all three types of DAA combination therapy achieved high SVR12 rates (94.6%-100%)[125]. Patients treated with SOF + IFN + RBV regimen showed marked HRQoL decrease from treatment week 2, and those treated with SOF + RBV experienced modest on-treatment HRQoL decline. For both groups,the HRQoL scores remained at trough level until EoT, before improving to and beyond pre-treatment levels[125]. In contrast, the HRQoL scores of patients receiving DAA-only treatment (LDV/SOF) started to improve from treatment week 4, and continued improving during and after the treatment period[125]. By week 12 posttreatment, the HRQoL scores of the LDV/SOF-treated group were significantly higher than those of the other two treatment groups[125]. Considering the good safety profile and tolerability documented for SOF/VEL in clinical and real-world studies,SOF/VEL is likely to have beneficial effects on PROs, similar to LDV/SOF. Other non-SOF-based, DAA-only regimens have also generally been associated with stable ontreatment PRO profiles and PRO improvements at EoT or post-treatment[126-130].

In summary, curing HCV infection is generally associated with improved patient experience and quality of life, irrespective of the therapy used. Again, the benefits availed by PR therapy are likely to be limited in the light of its low treatment success rate. In fact, poor adherence due to severe on-treatment HRQoL impairment is considered an important factor contributing to the low real-life SVR rates with PR therapy[4]. IFN-containing DAA combination regimens can achieve high SVR rates,but like PR therapy, are associated with severe PRO impairment during treatment.IFN-free, RBV-containing DAA regimens lead to mild on-treatment PRO impairment.In contrast, DAA-only regimens can avoid such negative impact on patients, and can confer rapid, sustained improvements in PROs during and after treatment. In resource-limited settings or in difficult-to-treat patients, the use of IFN and/or RBV may be a pragmatic necessity. Nevertheless, the need to minimize on-treatment life quality deterioration and to optimize patient experience should be taken into consideration when choosing the appropriate treatment regimens for HCV patients,and DAA-only regimens have demonstrated added value in this respect.

REMAINING CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Technical considerations in HCV management

In the DAA era, the goal of HCV elimination has become more realistic than ever.Nevertheless, there remain some challenges and important issues that deserve more attention in the management of HCV.

With existing pan-genotypic regimens, GT3 HCV tends to be more difficult to treat than the other genotypes. Both GLE/PIB and SOF + DCV require treatment duration extensions for certain subpopulations of GT3 patients, and SOF/VEL’s drug label in China suggests the addition of RBV for GT3, cirrhotic patients[5,131]. More research would be needed to optimize the treatment strategy for GT3 patients, especially in China where the proportion of GT3b subtype and the prevalence of baseline NS5A RASs are higher than in Western countries[51,132].

Special attention needs to be paid to patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus(HBV), which has a prevalence of 4.11% among HCV patients in China[133]. HBV/HCV coinfected patients not on active anti-HBV treatment should be monitored for potential HBV reactivation during and after DAA treatment[5].

Patients who fail certain DAA regimens may develop treatment-emergent RASs,the transmission and accumulation of which could potentially cause public health issues. A study on HCV resistance in China by Huanget al[134]. reported a significantly higher overall frequency of NS5A RASs in treatment-na?ve GT1b patients in 2016 than in 2008 (42.0%vs18.4%;P= 0.002). To minimize the risk of treatment-emergence RASs, it is important to select for initial treatment regimens with high resistance barriers (such as NS5B inhibitors), or to diligently conduct baseline RAS testing if planning to use regimens known to be prone to clinical resistance. SOF/VEL/VOX,the regimen reserved for rescue treatment of patients with DAA failures, is not yet available in China, but would likely be a valuable tool in the future as more and more Chinese patients undergo DAA treatments.

While DAAs offer high rates of virologic cure, the issue of HCV reinfection is coming increasingly into attention. High reinfection rates associated with high risk behaviors may hamper HCV elimination in key populations, such as IDUs and MSM.For patients prone to high-risk behavior, reinfection risk counseling and linkage to harm reduction services should be provided before and after HCV treatment, such as referring actively injecting IDUs to methadone substitution treatment or needle and syringe exchange programs, linking MSM to condom distribution programs, and other behavioral interventions where necessary[135].

Besides curative therapies, another approach explored for facilitating HCV elimination is the development of prophylactic HCV vaccines. Faced with challenges ranging from the high genetic variability of HCV to a lack of appropriate animal model systems for efficacy evaluation, research in this area thus far has not met with success (for research progress on vaccine candidates, please refer to reviews by Ghasemiet al[136]and Yanet al[137]).

Value assessment and other considerations in healthcare policy making

In addition to the value aspects discussed in this article, there are other factors pertaining to curing HCV infection that, though not yet incorporated into value assessment models, obviously carry considerable importance for patients and society.For example, the hope of being cured and the removal of societal stigmatization would be valuable from individual patients’ perspectives. Often, HCV patients are ostracized by the community and discriminated in the workplace. Individuals diagnosed with HCV infection may suffer from anxiety and fear, and some may feel hopeless and give up on seeking treatment. However, with the availability of highly effective DAA therapies, the possibility of achieving a complete cure with relatively short and well tolerated treatments would help alleviate the fear in many patients and contribute towards destigmatizing HCV infection. Another such example is the scientific “spill-over” effect, whereby introducing and investing in innovative treatment technology may stimulate future research for better understanding of HCV and advancement in HCV prevention and control. It could be worthwhile for Chinese researchers to explore how these aspects can be incorporated into novel value assessment models to better inform health technology assessment and public health policy making.

With the first DAA regimens approved in 2017 and the registration process expedited for innovative HCV medicines, China is undoubtedly shifting from the PR era towards that of DAAs for HCV treatment. In light of the principles set out in the 2017-2020 National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan and the goals of the Healthy China 2030 Plan, we would like to suggest that Chinese policy makers take further measures to improve the availability of, and enable large-scale access to, innovative HCV treatment, so as to capitalize fully on the value of effective HCV cure.

In order to maximize the benefits of highly effective HCV treatment, it would be essential to have as many HCV-infected patients as possible diagnosed and treated.The targets set out in the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis are that, by 2030, 90% of HCV-infected patients are diagnosed and 80% of those diagnosed receive HCV treatment[5]. In this respect, efforts would be needed from Chinese policy makers and healthcare professionals to improve the public awarenessof HCV through continued education. Public health resources would also be needed to support the service coverage of HCV screening, diagnosis, and linkage to care.Specifically, targeted efforts and aids may be needed to ensure that the diagnosis and treatment needs are met in rural and less developed areas of China, and that HCV management capabilities can be enhanced in lower-tier hospitals and healthcare facilities.

CONCLUSION

The value of curing HCV infection extends far beyond the clinical endpoint of SVR. At patient level, achieving virologic cure improves the long-term health outcomes and quality of life. At society level, providing prompt and effective treatment can help avoid future HCV-related disease and financial burdens. As China stands on the threshold of the DAA era, it would be important for stakeholders and policy makers to consider, that when evaluated holistically, the long-term benefits associated with curing HCV infection would outweigh the initial investment needed for implementing effective HCV therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mei Kwan Chan, MSc and Bo Lyu, PhD (employees of Costello Medical, Singapore, funded by Gilead Sciences, Shanghai, China), for writing assistance and editorial support for the development of the manuscript. The authors are entirely responsible for the scientific content of this paper.

World Journal of Hepatology2019年5期

World Journal of Hepatology2019年5期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Successful treatment of noncirrhotic portal hypertension with eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A case report

- Neonatal cholestasis and hepatosplenomegaly caused by congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type 1: A case report

- Carvedilol vsendoscopic variceal ligation for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding: Systematic review and metaanalysis

- Expanding etiology of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- Hepatitis C virus antigens enzyme immunoassay for one-step diagnosis of hepatitis C virus coinfection in human immunodeficiency virus infected individuals

- Roles of hepatic stellate cells in acute liver failure: From the perspective of inflammation and fibrosis