Short lessons in basic life support improve self-assurance in performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Mario Kobras, Sascha Langewand, Christina Murr, Christiane Neu, Jeannette Schmid

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Asklepios Western Clinical Centre, 20 Suurheid, City of Hamburg 22559, Federal Republic of Germany

2Academy of the Rescue Service Cooperation in Schleswig-Holstein, 50 Esmarch Street, City of Heide 25746, Federal Republic of Germany

3Regio Clinical Center GmbH, Sana Group, 71–75 Ramskamp, Elmshorn 25337, County of Pinneberg, Federal Republic of Germany

4Executive Committee of the Goethe University, Frankfurt a.M., City of Frankfurt 60323, Federal Republic of Germany

Corresponding Author: Mario Kobras, Email: m.kobras@asklepios.com

Short lessons in basic life support improve self-assurance in performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Mario Kobras1, Sascha Langewand2, Christina Murr2, Christiane Neu3, Jeannette Schmid4

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Asklepios Western Clinical Centre, 20 Suurheid, City of Hamburg 22559, Federal Republic of Germany

2Academy of the Rescue Service Cooperation in Schleswig-Holstein, 50 Esmarch Street, City of Heide 25746, Federal Republic of Germany

3Regio Clinical Center GmbH, Sana Group, 71–75 Ramskamp, Elmshorn 25337, County of Pinneberg, Federal Republic of Germany

4Executive Committee of the Goethe University, Frankfurt a.M., City of Frankfurt 60323, Federal Republic of Germany

Corresponding Author: Mario Kobras, Email: m.kobras@asklepios.com

BACKGROUND: There are several reasons why resuscitation measures may lead to inferior results: difficulties in team building, delayed realization of the emergency and interruption of chest compression. This study investigated the outcome of a new form of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training with special focus on changes in self-assurance of potential helpers when faced with emergency situations.

METHODS: Following a 12-month period of CPR training, questionnaires were distributed to participants and non-participants. Those non-participants who intended to undergo the training at a later date served as control group.

RESULTS: The study showed that participants experienced a signifi cant improvement in selfassurance, compared with their remembered self-assurance before the training. Their self-assurance also was signifi cantly greater than that of the control group of non-participants.

CONCLUSION: Short lessons in CPR have an impact on the self-assurance of medical and non-medical personnel.

Basic life support; Simulation training; Non-technical skills; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

World J Emerg Med 2016;7(4):255–262

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrest situations are still a great challenge for most people who fi nd themselves in the helper's position. Because of suffered stress and group coordination problems support measures are often taken too late or insufficiently.[1]Research has been directed on the improvement of survival rates in patients who had been receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and means of improvement of helpers' skills in emergency situations.[2]

It is common knowledge that delayed or interrupted CPR leads to deterioration of brain and heart function.[3,4]Even if the neurological fi ndings are good, survivors still show an impairment of memory functions.[5]There is still an urgent need for continuous improvement of understanding life-threatening situations as well as an improvement of communication and technical performance of helpers in such situations.

A lot of empirical evidence in this field stems from simulation studies, in which cardiac arrest situations are simulated in a clinical environment. As an alternative, there are technical devices available which offer data for subsequent analysis and expert feedback of a cardiac arrest situation, such as recording devices or CPR-sensing defibrillator/monitor units.[6]To our knowledge there has not been any real time study about the onset of a cardiac arrest for lay helpers yet.[7]In simulation studies hands-on-time on patients – meaning direct action such as chest compression or artificial ventilation– usually shortens when communication and leadership are less than optimal.[8–11]Rescuers who arrive later on the scene often get insuffi cient information from the fi rst responders.[12]A quick decision to begin CPR results in a better outcome,[13]if cardiac arrest occurs. Brief instructions in team-based situations and quick teambuilding help to coordinate CPR actions and to avoid performance breaks.[8,9]Thinking aloud and staying alert for wrong information during a CPR session improve team performance.[14]Marsch et al[15,16]showed that in the simulator unnecessary interruptions of chest compression were not noticed by the team members during performance. Only the subsequent debriefing made them aware of the discontinuities which might have resulted in severe damages to a real patient. All of these facts have been considered in the CPR guidelines which have been published by the European Resuscitation Council (ERC).[17]

However, most efforts to improve CPR performance through the use of simulations can help to specialize nurses and other medical staff like intensive care personnel. Improving CPR performance of lay helpers without medical education is much more difficult and not subject to simulation training yet. Although there are standardized CPR classes, survival rates after pre-clinical resuscitation have not improved over the years.[18]

Many non-trained people show hesitation and lack of self-confidence when facing cardiac arrest situations.[19]Social status and group membership seem to play a role in team building and administration of helping tasks.[20–22]Most German citizens only undergo CPR training once in their life as a requirement for their driver's license. So it is only to be expected that in the early phase of resuscitation lay helpers may struggle to retrieve their theoretical knowledge and to provide sufficient help. Medical personnel who are not part of a special rescue team undergo a comparable experience when faced with a cardiac arrest.[14]Faced with a severe situation the time span between noticing an emergency and taking action by beginning chest compression is very much longer in non-trained persons.[19]

CPR skills can be improved by implementation of regular training sessions and direct feedback.[23]Even training programs in middle schools can help.[24]Continued chest compression only results in comparable survival rates to continuous chest compression combined with artificial ventilation in early resuscitation.[25]Therefore, continued chest compression seems to play the more essential part in resuscitation,[26]which potentially makes CPR actions easier for lay helpers at the onset of an emergency situation. Standardized short phrases have been found useful during professional performance of CPR which also may help to continue lay help measures.[27]

We initialized an innovative project to increase patients' security in hospitals. All employees, e.g. medical and non-medical staff of a three center hospital got the opportunity to participate in a special training in basic life support (BLS). The aim was to use short lessons to teach CPR techniques as well as non-technical skills to first responders in a potential cardiac arrest situation. It has been shown that short lessons can improve retrieval technical skills in a cardiac arrest situation.[28]This method was expected to improve self-assurance in emergency situations in general and correct chest compression specifi cally.[28]

A period of 12 months of BLS trainings was determined to be a pilot phase. Participation was voluntary. With expected self-assurance in a cardiac arrest situation as the dependent variable, participants in the training were compared to non-participants.

METHODS

The study compared participants in the courses to non-participants. The participants were questioned after they had undertaken the training (post treatment measurement). The non-participants were classifi ed in 2 groups: a) non-participants who were willing to undergo the training at a later date and b) non-participants who did not intend to take the training. An additional group, the coaches, proved too small in numbers to be included in subsequent analyses. This resulted in a 1×3 post-hoc design with the participants, the willing non-participants and the unwilling non-participants as the conditions.

The project has been approved by the hospital's fi nancial director, the head of the hospital's nursing school, the head of rescue service and the medical director. Since actual patients were not involved in the study and because participation was voluntary the ethics committee referred approval to the work council. Full approval was given after reviewing the questionnaires.

Training

Before implementing regular training lessons for hospital personnel, a special training for BLS-coaches was provided by the regional academy for paramedics(“RKiSH–Rettungsdienstkooperation in Schleswig-Holstein“, Germany). This was done to guarantee a comparable performance in the lessons given to the employees later on. Medical knowledge was not required to participate in this training. The coaches were trained in standardized CPR actions according to the guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) from 2010. Additionally they were familiarized with group dynamics and confl ict situations in an adult education context and received coping instruction.[29,30]In these 2-day sessions the coaches got the opportunity to reflect and improve their teaching skills. After performing a trial lesson each BLS-coach was accredited to give BLS lessons to medical and non-medical employees at the hospital without further supervision.

The actual BLS lessons for employees were given at all of the four facilities of Regiokliniken in the county of Pinneberg, Germany (3 hospitals, 1 administration building) by the BLS-coaches. Each employee was able to choose a date for the training session from a schedule with several options. The groups were formed of 8 to 16 participants with different levels of medical knowledge.

The BLS short lessons comprised technical skills like performing correct chest compression on a manikin (Resusci Anne, Laerdal) or the correct use of a ventilation bag. In view of empirical evidence that chest-compression-only CPR shows similar survival rates to chest compression with ventilation in early resuscitation[25]we decided to emphasize the importance of chest compression. Also for hygienic reasons it would have been mandatory to change the manikin's face for every course participant. This requirement would have prevented a realistic BLS work flow. To maintain selfprotection untrained lay helpers are not bound to perform mouth-to-mouth-ventilation in Basic Life Support in Europe.[31]But to show a 2-helper sequence properly we needed a form of ventilation. The use of a ventilation bag was taught to the participants as a special skill for hospital employees.

Cardiac arrest scenarios were created in which two participants had to perform BLS. Since the scenarios were simulated for two helpers we taught a simple maneuver to change positions (ventilation or chest compression).

Because of recent findings in simulation studies[8]there was an additional emphasis on non-technical skills like simple and clear communication. Theoretical content was kept short in the lessons to provide more time for active training.[9–11]

The participants learned how to shorten or avoid interruptions of CPR by speaking aloud phrases like“chest compression has to be deeper“ or “keep going chest compression“ or “do not leave the patient“. If misunderstandings occurred, participants were told to repeat the information. The instructor used phrases like “just continue your action and repeat your information, do not be hasty, it is alright“. This aimed to reduce unnecessary stress. When interruption of chest compression occurred the BLS coach immediately advised them to continue chest compression.

After the pilot-phase of 12 months of BLS-training at the hospital we received a list of employees who took part in a BLS training session and of those who did not. The list was provided by the personnel director and certifi ed by the work council of the company. Since the participants were only made known to us after they had undergone the training, pretests were not possible and it was decided that a between-group design with nonparticipants as a control group was to be adopted.

Data collection and variables

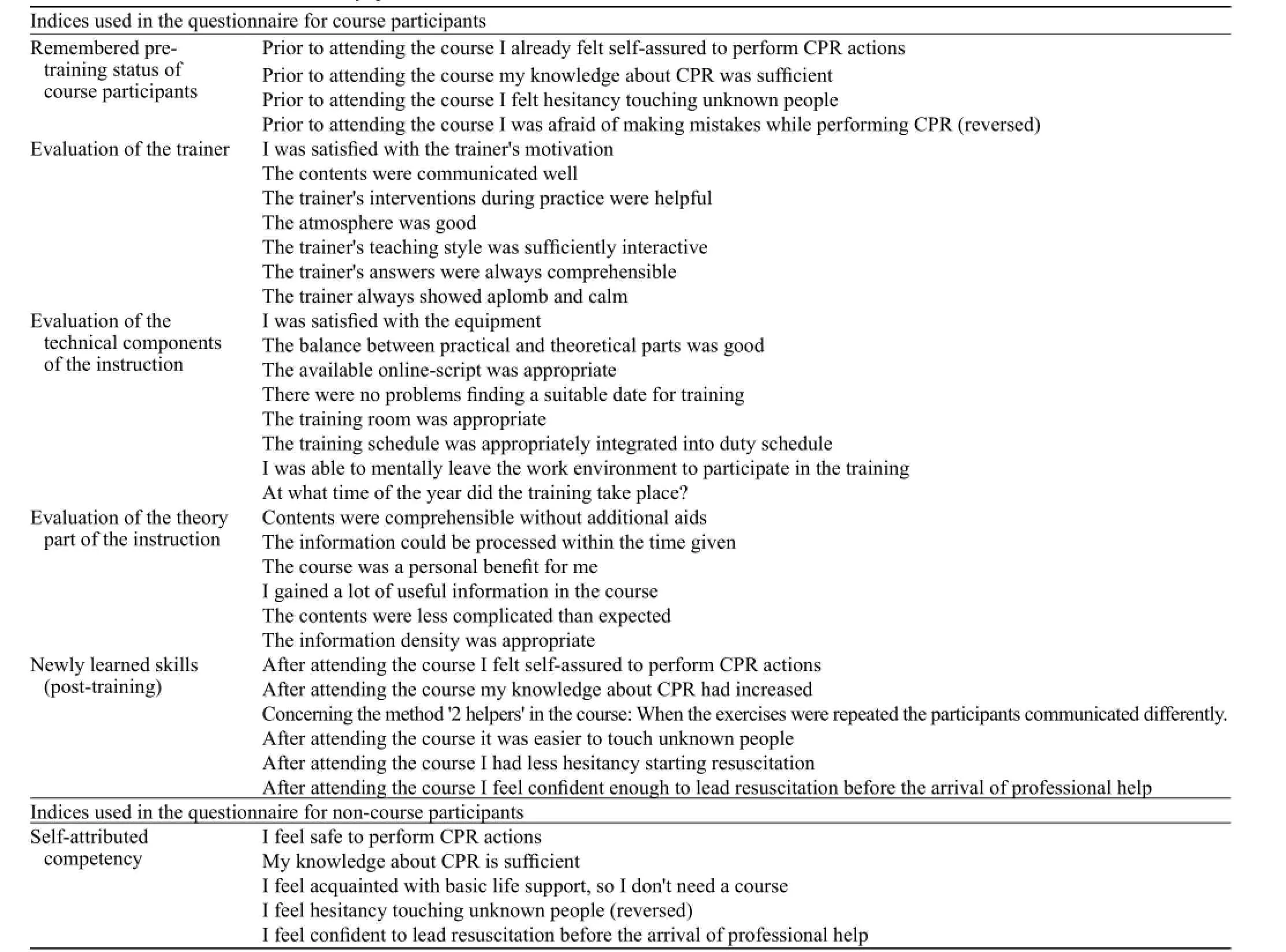

Preliminary discussions with health workers resulted in three questionnaires, designed specifically for this study: one for participants, one for non-participants and one for the coaches. Whenever possible, Likert scales were used: “strongly agree–agree–undecided–disagree–strongly disagree“. The questionnaires had several questions in common (medical experience and working position in the hospital) but differed in other aspects. Table 1 compares the questionnaires for participants and for non-participants.

To improve reliability, the questions were grouped according to topic and combined to an index per topic (unweighted average of scale values). Only items with the same scale wording were combined. Care was taken regarding the evaluation direction, so that values were reversed for some items previous to the computation of the index. The 5 indices for participants were: 1) remembered pre-training-status/competency of participants; 2) evaluation of the coach; 3) evaluation of technical components of the instruction; 4) evaluation of the theoretical part of the instruction; 5) acquisition of new skills. For the non-participants 5 items were combined to an index of self-attributed competency. Table 2 gives the details and lists the items.

Additionally we categorized two levels of professional experience in participants. It was argued that previously unexperienced participants could potentially profit from the training to a higher degree than experienced professionals. Higher experience wasattributed when participants declared their professional status as medic or as someone with an even higher level of medical education and/or when participants reported an involvement in cardiac arrest situations on two or more occasions. Employment was categorized as either patient-related (physician, nurse, physiotherapist, etc.) or as non-patient related (administration, maintenance, etc.).

Table 1. Participants and non-participant questionnaire: Parallel and specifi c topics, number of questions and examples

Table 2. Combined indices used in study questionnaires

Whereas the participants had discovered news of the courses via diverse digital and non-digital communication channels, they all received their questionnaires as hardcopy mail via the internal post-offi ce. The participants had two weeks to respond. Participants in this study did not receive any rewards because the collection of the completed questionnaires was conducted anonymously.

One focus of this study was the evaluation of the BLS-training. It was expected that the training should improve the self-attributed skills and the self-confi dence subjectively as well as objectively when compared to an untrained group. A second focus was on people who decided against a training session. Here the study was a pilot to investigate the individual decision for or against a BLS training session.

Statistical analysis

Calculations were done using the software IBM?SPSS?Statistics Version 22. Parametric tests (ANOVA, Mann-Whitney-U-Test, Pearson Correlation Tests) were employed for parametric data. Nonparametric comparisons were computed with Chi2- or Wilcoxon-Tests, depending on the distribution characteristics of the variables.

RESULTS

Participants

The analysis was based on 143 questionnaires returned by participants of the training intervention (return rate: 40%). We received 314 questionnaires from non-participants (return rate: 25%). Thirty-two employees were excluded because they were involved in the planning of this study. An additional exclusion of questionnaires was not necessary. Participants were predominantly from the medical field. Eightyfour percent of this group had frequent contact with patients. The larger part of the group was female (73%). Sixty percent came from a professional medical field, whereas 40% came from working fields which usually do not involve direct patient treatment. In the interest of anonymity the respondents did not have to give their exact age, but had to indicate their respective age group: under 18, 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, over 65. Q1 was in age group 36–45, median and Q3 in age group 46–55, which was the largest age group with 40.6% of the participants.

The majority of non-participants were medical staff (52%) and 64% had regular contact with patients. Female accounted for 75.5% of the non-participants. The nonparticipants' age groups ranged from 18 to over 65 years old with the largest group (32.8%) at 46–55 years. The group of originally 20 coaches turned out to be smaller than expected with just 11 potential respondents. Only 5 returned the questionnaires so statistical analysis of this group was skipped.

In the group of non-participants, 219 out of 314 explicitly stated that they wished to participate in a training session at a later time. They served as control group for those participants who had undergone the training. The choice of this select group as control group excludes willingness to participate as a mediating factor in the results. The logic of a comparison group demands that – barring the feature that has to be investigated –every other aspect of the groups should be as similar as possible.[32]With the willing participants we therefore selected the one group that differed from the treatment group only in the fact that they did not (yet) receive the training and not additionally in their initial opinion about the usefulness of the training.

Effects of the training

The factor age-groups had no significant impact on self-assurance, but gender had: males reported a higher self-assurance [Mmale=2.11, SD=0.97; Mfemale=2.68, SD= 1.20; t (352) =–3.86; P<0.001]. Respondents with a higher level of professional experience also reported higher self-assurance: Mhighexp=2.09, SD=0.87; Mlowexp= 3.51, SD=1.18; t (358)=12.75, P<0.001.

As an indication of objective improvement, the selfassurance of the willing non-participants was compared to the post-training self-assurance of the participants.

In comparison to the control group, those who underwent the training reported more perceived selfassurance in situations that required emergency measures; while the average non-participant reported a medium self-assurance, participants declared that they felt mostly self-assured [Mpart=2.08; SD=0.89; Mcontrol=2.85; SD=1.24; t (358)= 6.82; P<0.001].

An inclusion of the level of expertise as a mediating factor reduced this effect to non-significance; however, the interaction between level of expertise and participation versus non-participation became highly significant: F (356) = 20.58, P<0.001 with Mparticipant_expert=1.84, SD=0.75;Mparticipant_nonexpert=2.64; SD=0.98; Mnonparticipant_expert=2.27, SD=0.91; Mnonparticipant_nonexpert=4.01, SD=0.97. For less experienced respondents the effect of the training on selfassurance was more pronounced. Level of experience was significantly correlated with patient-related or not patient-related employment (r=0.63, P<0.001), but the effect of employment on the difference between control group and participants regarding self-assurance was smaller.

In the participant group post-training self-assurance was correlated with the index of measurements of newly learned skills: r=0.30, P<0.001; the latter index was also correlated with actual perceived knowledge: r=0.75, P<0.001.

There is also a subjective improvement in the group of training participants:

Participants were asked to rate their characteristics regarding self-assurance and inhibition in the treatment of patients before they underwent the training. A retrospective inquiry into the state of mind at an earlier date should not be confused with a measurement taken before treatment. It involves memory biases and is done in hindsight. It provokes a comparison of the actual state with the one remembered and thus serves as an indication of subjective improvement.[33]

They remembered their self-assurance pretraining as significantly lower [lower values indicate higher agreement with actual assurance post-training; Mpre=2.60; SD=1.17; Mpost=2.09; SD=0.89; t (140)=6.12, P<0.001]. Their remembered knowledge pre-training was significantly lower as well [Mpre=2.57, SD=1.16; Mpost=1.99, SD=1.09; t (135)=4.01, P<0.001]. While gender or age group had no signifi cant effect, there was an interaction with level of experience for self-assurance with F (139)=13.92, P<0.001 with less experienced participants indicating greater subjective improvement. Including the factor experience as covariate did not reduce the signifi cance of the main effect.

There was a positive correlation of remembered initial confidence with subsequent self-assurance (r= 0.61, P<0.001) signifying a dependency of these two measurements.

As for the influence of the perceived quality of the training on actual self-assurance of participants. A higher actual self-assurance was reported when the content of the training intervention matched the real life experience: r=0.40, P<0.001. Evaluation of trainer performance correlated highly with improved self-assurance in cardiac arrest situations (r=0.33, P<0.001).

Reported post-training knowledge correlated significantly with the quality ratings for the theoretical part of the training (r=0.61, P<0.001) as well as with the evaluation of the technical components of the training (r=0.39, P<0.001).

Reasons for non-participation

BLS lessons were taken on a voluntary basis, so not every employee took part. A number of non-participants had stated in the questionnaire that they intended to participate in the training at a later date and just could not accommodate the dates presently available for training. These were compared to those who stated that they had no intention to participate at some later date. We found that employees in the non-participant-group who indicated more hesitancy to touch patients also were less willing to take part in a BLS lesson compared to persons who declared to be less hesitant [Mnonwilling=3.92, SD=1.35; Mwilling=4.39, SD=0.89; t (83)=–2.62, P<0.01]. Self-attributed knowledge about CPR did not differentiate between willing and non-willing nonparticipants, but self-assurance did (lower numbers indicating higher assurance): Mnonwilling=3.27, SD=1.49; Mwilling=2.85, SD=1.24; t (88)=2.05, P<0.01.

The willingness to participate increased with: a) level of experience [Chi2(1, 286)= 9.05, P<0.003] and b) patient-related employment [Chi2(1, 257)=9.43, P<0.01]. Non-participants with a medium level education were most willing to participate: Chi2(4, 277)=21.62, P<0.001. Neither gender nor age group differentiated between non-participants who intended to take the training at a later date and those who did not.

DISCUSSION

The actual self-assurance of participants at the time they answered the questionnaire was signifi cantly higher than their remembered pre-training assurance. Their selfassurance was also higher in comparison with the control group.

This was an expected result and indicated the effectiveness of the training in this regard. While gender and age did have no impact on the decision to participate and on the actual training outcome, the patient-relatedness of employment as well as the actual experience in emergency situation played an important part. It may be that persons who do not have a lot of patient involvement do not see the necessity of getting that sort of training, even though it would be an asset in out-of-hospital emergency situations. It may also be that for less experienced people the prospect of interactingwith a patient in an emergency situation (even though it is just simulation training) might have caused some anxiety. Results, however, indicate that it is the less experienced potential participants who would profi t most from these short lessons in BLS.

Another aspect are limitations of methodology and generalization of results. There was no pretrainingposttraining comparison within the group of participants so the training effect had to be estimated by comparison with a group of non-participants who were willing to have the training at a later date.

It could be argued that the high scores after the training could be partly due to a hello-goodbye-effect[34]that leads to an overestimation of training effects. However, the time spread between training and questionnaire application varied greatly from a few weeks to almost a year and there was no signifi cant correlation between post-training self-assurance and time interval between training and questionnaire.

The participants could not be observed in a subsequent real emergency situation, so it remains to be proven that post-training self-confidence carries over to real life emergency. The fact that self-assurance after training did improve, however, is a crucial training effect, for to be assured of one's competence is a prerequisite for effective action. However, it is not a sufficient condition, for situational components also do play a part in individual decisions to give assistance.[35]

One problem still remains. As we showed in the present study people from non-patient-related work fi elds show hesitation in touching people which may be the main reason for poor outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. At the same time, this hesitation to touch people could be a hindrance to attend a BLS training program. The promotion of future BLS trainings should take that into account. In our opinion BLS short lessons are a good way to improve the outcome of cardiac arrests by simplifying the topic for potential helpers. If the contents are conveyed in the right way hesitation in emergency situations may diminish and continued chest compression might be performed by lay helpers instead of keeping hands off the patient. Immediate CPR, even if of low quality, can lead to better survival than delayed high-quality CPR, as shown by Song et al.[36]They found better survival by immediate low quality CPR than in delayed high quality CPR in rats. Aside from the continuous improvement of the practical and theoretical part of the training, the fi rst step, engaging the interest of potential participants, should get more attention.

In the end of 2015 CPR guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council were published in revised form.[31]In comparison to the former guidelines from 2010, the new guidelines for Basic Life Support have been simplified for lay helpers. These simplifications and additionally aspects of group dynamics and communication were already part of the training preceding this pilot study. The results support the validity of this training program.

In conclusion, the present study attempted to substantiate the claim that teaching Basic Life Support in short lessons helps to improve self-assurance in hospital employees when faced with a cardiac arrest situation.[37–39]It evaluated a pilot phase of a newly introduced in-hospital training.

However, this study also gives some indications of the difficulties to motivate lay-helpers to take that training. Subsequent studies should address that issue as well.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Since actual patients were not involved in the study and because participation was voluntary the ethics committee referred approval to the work council. Full approval was given after reviewing the questionnaires.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare there is no competing interest related to the study, authors, other individuals or organizations.

Contributors: Kobras M proposed the study and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the fi nal version of the paper.

REFERENCES

1 Hunziker S, Laschinger L, Portmann-Schwarz S, Semmer NK, Tschan F, Marsch SC. Perceived stress and team performance during a simulated resuscitation. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37: 1473–1479.

2 Hunziker S, Johansson AC, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Rock L, Howell MD, et al. Teamwork and leadership in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 2381–2388.

3 Yu T, Weil MH, Tang W, Sun S, Klouche K, Povoas H, et al. Adverse outcomes of interrupted precordial compression during automated defi brillation. Circulation 2002;106: 368–372.

4 Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Hallstrom AP. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann Emerg Med 1993; 22: 1652–1658.

5 Sulzgruber P, Kliegel A, Wandaller C, Uray T, Losert H, Laggner AN, et al. Survivors of cardiac arrest with good neurologicaloutcome show considerable impairments of memory functioning. Resuscitation 2015; 88: 120–125.

6 Abella BS, Edelson DP, Kim S, Retzer E, Myklebust H, Barry AM, et al. CPR quality improvement during in-hospital cardiac arrest using a real-time audiovisual feedback system. Resuscitation 2007; 1: 54–61.

7 Johnson BV, Coult J, Fahrenbruch C, Blackwood J, Sherman L, Kudenchuk P, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation duty cycle in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2015; 87: 86–90.

8 Hunziker S, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Zobrist R, Spychiger M, Breuer Marc, et al. Hands-on time during cardiopulmonary resuscitation is affected by the process of teambuilding: A prospective randomised simulator-based trial. BMC Emerg Med 2009; 9: 3.

9 Hunziker S, Bühlmann C, Tschan F, Balestra G, Legeret C, Schumacher C, et al. Brief leadership instructions improve cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a high-fidelity simulation: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1086–1091.

10 Hunziker S, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Howell MD, Marsch SC. Human factors in resuscitation: lessons learned from simulator studies. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010; 3: 389–394.

11 Tschan F, Vetterli M, Semmer NK, Hunziker S, Marsch SC. Activities during interruptions in cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a simulator study. Resuscitation 2011; 82: 1419–1423.

12 Bogenst?tter Y, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Spychiger M, Breuer M, Marsch SC. How accurate is information transmitted to medical professionals joining a medical emergency? A simulator study. Hum Factors 2009; 51: 115–125.

13 Abella BS, Sandbo N, Vassilatos P, Alvarado JP, O'Hearn N, Wigder HN, et al. Chest compression rates during cardiopulmonary resuscitation are suboptimal: A prospective study during in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2005; 111: 428–434.

14 Tschan F, Norbert NK, Gautschi D, Hunziger PR, Spychiger M, Marsch SC. Leading to recovery: group performance and coordinative activities in medical emergency driven groups. Human Performance 2006; 19: 277–304.

15 Marsch SC, Tschan F, Semmer N, Spychiger M, Breuer M, Hunziker PR. Unnecessary interruptions of cardiac massage during simulated cardiac arrests. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2005; 22: 831–833.

16 Marsch SC, Tschan F, Semmer N, Spychiger M, Breuer M, Hunziker PR. Performance of first responders in simulated cardiac arrests. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 963–967.

17 Nolan JP, Soar J, Zideman DA, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Deakin C, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 1219–1276.

18 Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, Kreuter W, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 22–31.

19 Koster R. Modern BLS, dispatch and AED concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013; 27: 327–334.

20 Berger JM, Fisek MH, Norman RZ, Zelditch M. Status characteristics and social interaction: an expectation states approach. New York, NY: Elsevier Scientifi c, 1977.

21 Goar C, Sell J. Using task defi nition to modify racial inequality within task groups. Sociol Q 2005; 46: 525–543.

22 Lucas J. Status processes and the institutionalization of women as leaders. Am Sociol Rev 2003; 68: 464–480.

23 Edelson DP, Litzinger B, Arora V, Walsh D, Kim S, Lauderdale DS, et al. Improving in-hospital cardiac arrest process and outcomes with performance debriefi ng. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1063–1069.

24 Rekleiti M, Saridi M, Toska A, Kyriazis I, Kyloudis P, Souliotis K, et al. The effects of a fi rst-aid education program for middle school students in a Greek urban area. Arch Med Sci 2013; 9: 758–760.

25 Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, Berg RA, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, et al. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiaconly resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2007; 116: 2900–2907.

26 Hüpfl M, Selig HF, Nagele P. Chest-compression-only versus standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A meta-analysis. Lancet; 376: 1552–1557.

27 Hunt EA, Cruz-Eng H, Bradshaw JH, Hodge M, Bortner T, Mulvey CL, et al. A novel approach to life support training using“action-linked phrases“. Resuscitation 2015; 86: 1–5.

28 Nishiyama C, Iwami T, Murakami Y, Kitamura T, Okamoto Y, Marukawa S, et al. Effectiveness of simplified 15-min refresher BLS training program: a randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation 2015; 90: 56–60.

29 Negri C. Applied psychology for company development, concepts and methods for education, management and further training. Springer, 2010. ISBN-13 978-3-642-12624.

30 Dobler G. Rescue service instructor - means to get a successful trainer. 2015. ISBN-13: 978–3943174359.

31 Perkins GD, Handley AJ, Koster RW, Castrén M, Smyth MA, Olasveegen T, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defi brillation. Resuscitation 2015; 95: 81–99.

32 Shadish W, Clark M. 'Comparison Group', in Michael S. Lewis-Beck, A Bryman, Tim Futing Liao (eds), Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, 2004; 154–156.

33 Hassan E. Recall bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology 2005; 3: 339–412.

34 Choi BK, Pak AW. A catalogue of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chronic Dis 2005; 2: A13.

35 Hawks SR, Peck SL, Vail-Smith K. An educational test of health behavior models in relation to emergency helping. Health Psychol 1992; 11: 396–402.

36 Song F, Sun S, Ristagno G, Yu T, Shan Y, Chung SP, et al. Delayed high-quality CPR does not improve outcomes. Resuscitation 2011; 82 Suppl 2: S52–S55.

37 Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Factors modifying the effect of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 511–519.

38 Valenzuela TD, Roe DJ, Cretin S, Spaite DW, Larsen MP. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation 1997; 96: 3308–3313.

39 Andersen PO, Jensen MK, Lippert A, ?stergaard D. Identifying non-technical skills and barriers for improvement of teamwork in cardiac arrest teams. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 695–702.

Accepted after revision March 4, 2016

10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2016.04.003

Original Article

The training positive evaluations by the participants and led to an increase in self-assurance regarding future emergency situations. Due to the positive feedback of participants the training has been continued on a regular basis at Regiokliniken till today. We have yet to perform a follow-up study on the improvement of CPR performance following short lessons.

August 28, 2015

World journal of emergency medicine2016年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2016年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- Subject index WJEM 2016

- Author index WJEM 2016

- Stroke due to Bonzai use: two patients

- Emergency department diagnosis of a concealed pleurocutaneous fi stula in a 78-year-old man using point-of-care ultrasound

- When gastroenteritis isn't: a case report of a 20-yearold male with Boerhaave's syndrome complicated by intra-abdomimal hemorrhage