Integration of community health workers into health systems in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges

Collins Otieno Asweto, Mohamed Ali Alzain, Sebastian Andrea, Rachel Alexander, Wei Wang,

Integration of community health workers into health systems in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges

Collins Otieno Asweto1–3, Mohamed Ali Alzain1,3,4, Sebastian Andrea1,3, Rachel Alexander5, Wei Wang1,3,5

Background:Developing countries have the potential to reach vulnerable and underserved populations marginalized by the country’s health care systems by way of community health workers (CHWs). It is imperative that health care systems focus on improving access to quality continuous primary care through the use of CHWs while paying attention to the factors that impact on CHWs and their effectiveness.

Objective:To explore the possible opportunities and challenges of integrating CHWs into the health care systems of developing countries.

Methods:Six databases were examined for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies that included the integration of CHWs, their motivation and supervision, and CHW policy making and implementation in developing countries. Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria and were double read to extract data relevant to the context of CHW programs. Thematic coding was conducted and evidence on the main categories of contextual factors influencing integration of CHWs into the health system was synthesized.

Results:CHWs are an effective and appropriate element of a health care team and can assist in addressing health disparities and social determinants of health. Important facilitators of integration of CHWs into health care teams are support from other health workers and inclusion of CHWs in case management meetings. Sustainable integration of CHWs into the health care system requires the formulation and implementation of polices that support their work, as well as financial and non financial incentives, motivation, collaborative and supportive supervision, and a manageable workload.

Conclusions:For sustainable integration of CHWs into health care systems, high-performing health systems with sound governance, adequate financing, well-organized service delivery, and adequate supplies and equipment are essential. Similarly, competent communities could contribute to better CHW performance through sound governance of community resources, promotion of inclusiveness and cohesion, engagement in participatory decision making, and mobilization of local resources for community welfare.

Community health workers; health care systems and policy; supportive supervision; developing countries

Background

Globally, there is a renewed interest in the role of community health workers (CHWs) in strengthening health care systems and increasing availability of community-level primary health care services [1, 2], in line with the proposed 2030 sustainable development goal for health that aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages [3]. One of the targets of the sustainable development goal is to substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development,training, and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, and especially in the least developed countries and small-island developing states. However, developing countries face a challenge of providing primary health care to their populations because of limited funds.

CHWs have been de fined as lay persons who have received some training in delivering health care services but are not health care professionals [4]. In 1989 the World Health Organization stated that CHWs “should be members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system, but not necessarily a part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers” [5].

Evidence shows that CHWs operating in diverse countries and contexts can improve people’s health and well-being [6].Therefore the optimum functioning of CHWs in developing countries is critical to improvement of population health [7].In addition to extending the reach of the existing mainstream health system [8], CHWs can serve as cultural mediators or change agents for grassroots community engagement in improving health outcomes [8]. CHWs have been proposed as a means of ‘bridging the gap’ in the current health care systems in many developing countries but have also been shown to have a role in promoting chronic disease management in developed countries [9, 10].

CHW programs face many challenges – namely, weak political endorsement, financial constraints, fragmented oversight and technical support, lack of a common and wellfunded research agenda, and strategies to enhance and sustain CHW performance [11–15]. Nevertheless, policy makers, program managers, public health practitioners, and other stakeholders need guidance and practical ideas for how to support and retain CHWs. New ideas may emerge from the recognition that CHWs function at the intersection of two dynamic and overlapping systems – the formal health system and the community.

Although studies have shown the effectiveness of some CHW programs, implementation of these programs at scale and in resource-constrained settings has proved difficult [16].A common challenge concerns human resource management:how to ensure the retention, motivation, and sustained competence of CHWs, who often have limited education, operate in isolation far from health facilities, and sometimes receive only nominal pay.

Methodology

The literature review (Fig. 1) focused on integration of CHWs into health systems of developing countries, because most of the evidence on community-level primary health care was related to CHWs.

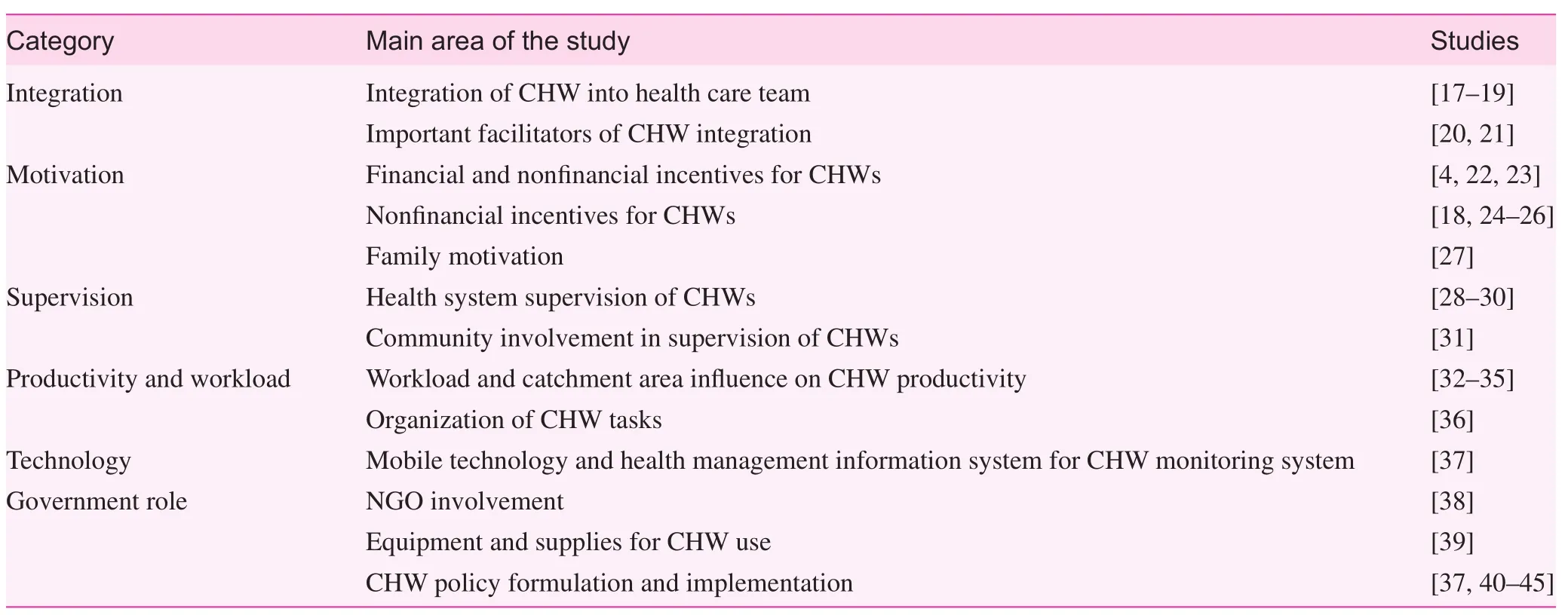

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies on CHWs working in promotional, preventive, or curative primary health care in developing countries were included. The review comprised studies on the supervision and motivation of CHWs; CHW workload and productivity; community involvement in CHW functions; technology use by CHWs;policy makers, health workers, and any other people directly involved in or affected by CHW service delivery (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of studies addressing contextual factors of sustainability and integration of community health workers into health systems of developing countries

The databases searched for eligible studies included EMBASE, PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, POPLINE, and NHS-EED. The search strategy was adapted from Lewin et al. [46] and is published elsewhere [47]. Reference lists of all relevant articles and reviews identified were also examined. English-language studies from 2007 to July 2015 provided a large number of‘hits.’

A framework approach [48] was used, with a preliminary conceptual framework [47] that included predefined categories of contextual factors affecting integration of CHWs into health systems. These categories were community context,policy context, health system factors, and government context, and they were based on a review of selected international literature [1, 49–51]. Two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified records to evaluate their potential eligibility. In instances where opinions differed, inclusion was discussed by the two reviewers until a consensus was reached. The full-text articles were double assessed by a team of four reviewers using a standardized data extraction form containing the description of the intervention, study, outcome measures, and predefined contextual factors. The quality of the literature included was further assessed independently by two reviewers, with an adapted version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme method[52]. Quality assessment of studies was conducted to decide on inclusion but the level of quality was not taken into account during data analysis as the methods of the included studies differed. Two reviewers analyzed the content of included articles using thematic coding, and the main categories of contextual factors influencing CHW performance from the preliminary conceptual framework were adjusted according to the findings [48].

Results and discussion

Integration

Despite meaningful efforts, CHWs have largely been excluded from the health care system because of funding and reimbursement issues [17]. However, on the basis of the experiences of some countries, it is increasingly suggested that CHWs should be fully integrated into health care systems [18]. Integration includes clearly delineated responsibilities within the health system, fair remuneration, and in some cases, the possibility of a career path [18]. CHWs are well suited to join care teams to address health disparities and social determinants of health. Previous studies on CHW integration emphasize work flow, communication, and electronic health record use [19].

The important facilitators of integration of CHWs into care teams include maintaining connection with and support from other health workers and inclusion of CHWs in well-run,consistent, organized meetings. Case management meetings involving CHWs allow the care team to understand critical pathways and issues patients face outside the health care setting and facilitate the exchange of information to help build cases or understanding of patients [20]. Case management and meetings with CHWs help to improve provider engagement with patients by encouraging them to take a more active role and assume responsibility in chronic disease management,encouraging collaboration, and helping to increase the CHW’s sense of autonomy [21].

Motivation of CHWs

Studies show that the performance of CHWs improves when they receive both financial and non financial incentives[4, 22, 23]. Examples of non financial incentives to frontline health workers and CHWs include preferential access to health care services for the worker and possibly his or her family at reduced cost (or free of charge), career growth opportunities, continuing education, mentoring and performance reviews, adequate supply of commodities and equipment needed by CHWs, recognition of outstanding performance, and provision of visible examples of a CHW’s special status (such as identification cards with a photograph, uniforms, or bicycles) [24–26].

One study suggested that countries deterred from paying salaries by fiscal and administrative constraints can nonetheless address the financial needs of CHWs through alternative income-generating activities such as loans and the selling of health-related products, opportunities for career advancement and professional development such as training and supportive supervision, and nonmonetary substitutes for remuneration such as transportation and supplies [18].It is suggested that such packages of incentives could allow CHWs to feasibly devote time to health-related activities that can reinforce their existing altruism and commitment to their work [18].

In the context of low levels of employment in the formal sector, CHWs gaining experience as health volunteers and acquiring skills is seen as a strategic step toward entry into professional health worker training, to obtain securer and better paid employment. Families have also been found to be a source of motivation [27]. Therefore, to sustain the family support, consider compensation packages that relieve the burden that CHWs can place on their families. In addition, financial incentives and in-kind alternatives allow CHWs to devote more time to their tasks and can make them feel more supported in their work, thereby reinforcing their altruism [27].

CHWs who perceive that their efforts are appropriately compensated and recognized and see long-term value in their role as CHWs may be better placed to provide higher-quality,essential services to the populations they serve. Policy makers and program implementers should use various sources of motivation as a guide to devise incentive structures that ensure the sustainability of CHW programs.

Supervision

According to Rowe et al. [28], supervision increases both the performance and the motivation of health workers. However,supervision of CHWs as traditionally provided by the health system alone is too infrequently implemented to be useful or effective [28]. In addition, supervisors may lack skills in problem solving and mentoring; thus supervision does not necessarily result in better performance care. Supervision is also often limited to fault finding [28]. Therefore have supportive supervision that focuses on mentoring, problem solving, and proactive planning [29]. Quality improvement programs in sub-Saharan Africa have suggested that supportive supervision and mentoring could help to achieve high-quality health services [29].

Involvement of community leaders and their health system partners is essential to successful collaborative supervision. Mkumbo et al. [31] recently showed that the involvement of village leaders in CHW supervision has the potential to increase the number of supervision contacts and improve the accountability of CHWs within the communities they serve.Practical, feasible, and supportive supervisory approaches that can be tailored to the local context and the diverse capacities and needs of communities. Therefore a new approach at the lowest administrative levels of the formal health system in partnership with communities is recommended, as it could result in higher-quality services provided by CHWs, improved health-promoting behaviors in the household, and greater health system utilization.

Some challenges with CHW supervision are not necessarily failures on the part of the program or supervisors but rather reflect unrealistic expectations of health workers, given human resource shortages and social constraints. Facility health workers, although important for technical oversight, may not be the best mentors for certain tasks such as community relationship building [30].

Productivity and workload

CHWs are frequently called on to address a range of essential service delivery needs, thus increasing their workload.According to Ruwoldt and Hassett [32], “a balanced workload improves CHW productivity, and the bene fits of addressing productivity include greater efficiency, increased job satisfaction, and higher quality of care.”

Apart from workload, CHWs also require capacity building, motivation, and support or a supportive environment to be productive [33, 34].

It may be possible to increase the range of services provided by CHWs by adjustment of the catchment population served by the CHW. The catchment area of a CHW comprises the number of households served, the target group within the family, and the geographic distribution of the households [35].Population coverage and the range of services offered at the community level are vital in the design of effective CHW programs, and the “smaller the population coverage, the more integrated and intensive the service offered by the CHWs”[35]. Programs should ensure that CHWs are able to satisfactorily reach all the targeted members within the speci fied geographic area and provide a standard level of quality of care.

The organization and scheduling of the tasks of CHWs can also assist in maximizing their productivity. Likewise, the manner in which CHWs are trained to perform the various tasks can in fluence productivity.

The workload of CHWs also needs to be compatible with their other responsibilities. For example, a CHW who farms for a living needs to be able to balance the requirements of farming with his or her work as a CHW. Currently, there is lack of evidence on how CHWs manage the competing demands of earning a livelihood and their responsibilities toward health care [36]. An understanding of CHW workload and use of time is thus important for effective management.

Technology use

Opportunities for improving the effectiveness of monitoring systems have increased with the availability of low-cost mobile technology. A practical, simple monitoring system using mobile technology that incorporates data from both the community and the health system can improve both accountability and CHW performance. A CHW performance monitoring system provides the basis for early detection of needs and problems, continuous learning, and identification of responses to individual and health system constraints. Traditionally, this kind of information has been collected more frequently by the health system through health record reviews, supervisor observations, and occasionally, home visits. A recent systematic review of the literature on CHWs and mobile technology found some promising evidence that mobile tools can help CHWs to improve both the quality and te efficiency of the services they provide [37].

Community support for CHWs could be further mobilized if members could be engaged to track the availability of essential supplies. Arrangements with private sector logistics firms to ensure the availability of critical commodities in the community may be possible where public sector organizations are unable or unwilling to include CHWs in their distribution networks.

Ideally, such a monitoring system should be synchronized with existing health management information systems. Most health management information systems are facility based,track the numbers of services provided rather than key processes, are often underutilized, and are a passive means of data collection. The monitoring system should be presented as an extension of the current health management information system, as a means of enhancing its utility by addressing some of its limitations. The monitoring system could also include data on the effectiveness of referral processes, which is a key factor in connecting the community and the health system.

Role of government

Countries that have successfully begun the process of addressing health needs of the poor have done so with high levels of government commitment. However, many developing countries rely heavily on donor funding to finance their health systems and are thus vulnerable to the vagaries of ability or willingness of donors to continue funding them. The involvement of nongovernmental organizations (NGO) has the potential to address some resource constraints in CHW support systems. However, findings highlight the risk of substituting rather than complementing government support functions,leading to a greater sense of accountability to NGOs than to district health staff. In addition, there is some evidence that NGO support might affect financial expectations, perhaps because of great exposure to incentives. NGO pullout is an important discouraging factor, stressing that sustainability in this approach is also problematic [38].

The governments in developing countries have a complex role to play in ensuring sustainability of the CHW support system, because it is key to universal health coverage and equity in quality of health care. Apart from providing enabling environments for the success of CHW programs, governments should play the leading role in providing adequate supplies and equipment, as well as policy formulation and implementation. Routine shortages of supplies and commodities erode the capacity of CHWs to deliver appropriate services, contribute to low demand for CHW services, and thereby negatively impact performance [39]. These shortages also contribute to CHW frustration and high job turnover. To perform their tasks effectively, CHWs need regular replenishment of supplies, medicines, and equipment. Transportation has also been identified as a problem CHWs face in performing their duties,highlighting weaknesses in infrastructure and logistics support [39]. By bringing services closer to communities, CHW programs eliminate transportation barriers for community members that limit their access to care. However, transportation problems are essentially shifted onto CHWs, who have to travel long distances to work.

Policies assist in anchoring CHWs within the primary health care systems and provide guidance on how CHWs can be involved within the health care system in serving the community. Hence policy makers and implementers of CHW interventions need to use the local context setting to achieve optimal performance. Understanding community practices and beliefs could assist policy makers in shaping CHW systems. CHW policy making has suffered from a lack of participation by communities and CHWs. The perspectives of CHWs themselves may reveal the contradictions of their roles more powerfully, highlighting areas of policy reform that are critical yet often neglected [40–43]. International actors sometimes impose certain policies on developing countries on the basis of evidence from other countries, not considering that differences in health systems and local values and conditions may undermine the transferability of evidence[37]. Therefore consider investing more in the development of locally relevant research for policy formulation [44]. In addition, the financial implications of CHW have fuelled policy maker resistance, especially given that governments are cautious in making commitment to pay CHWs. Whereas donors have tried to encourage policy change, they are reluctant to provide the significant additional funding that would be necessary [44] as external funding would affect sustainability of the CHW program.

The CHW policy process has also been hindered or delayed by health care professionals. For example, nonacceptance of CHWs’ use of antibiotics by clinicians was a major factor in slowing the integrated community case management policy process in Kenya [44]. The resistance was not only from professionals at the program level but also from high-level decision makers. There were clear technical underpinnings to these arguments. International evidence and guidelines were not sufficient to convince policy makers of the effectiveness of antibiotic use by CHWs, particularly given the contextual specificities and the negative outcome of the prior pilot program at Siaya [45]. However, these technical arguments were likely reinforced by bureaucratic concerns, including caution about allowing the emergence of a new group of health care providers who may undermine demand for regular health practitioners [44]. Resistance to policy change originated primarily from clinicians both inside and outside government and centered on concerns about the ability of CHWs to offer quality care and the potential consequences of inappropriate use of antibiotics by this cadre.

Conclusion

To ultimately improve health and well-being, specifically in marginalized communities, it is imperative that health care systems focus on functional methods to overcome the issues of disparities, cultural barriers, and poor communication.Creating a system that will improve access to quality continuous primary care reduces inequalities, help modify lifestyles,and is culturally acceptable and compatible with community values and norms is important.

As more countries look to implement CHW programs or transfer additional tasks to CHWs, it is critical that attention is paid to the elements that affect CHW productivity in the design phase as well as throughout the implementation of a program. An enabling work environment is crucial to maximizing the productivity of CHWs.

High-performing health systems with sound governance,adequate financing, well-organized service delivery, a capable and well-deployed health workforce, sound information systems, and reliable access to a broad range of medical products and commodities can reinforce CHW-specific programming.Similarly, competent communities could contribute to better CHW performance through sound governance of community resources, promotion of inclusiveness and cohesion, engagement in participatory decision making, and mobilization of local resources for community welfare.

The government’s role in anchoring CHW programs in the health care system would, through policy formulation and implementation, provision of supplies and equipment, and the creation of a favorable working environment in addition to supportive supervision, ensure sustainability of CHW programs. However, overreliance on external funding would be a barrier to integration of CHW programs in primary health care systems.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-pro fit sectors.

Author contributions

Collins Otieno Asweto contributed to study conception and design, review, drafting, and revision of the article. Mohamed Ali Alzain, Sebastian Andrea, Rachel Alexander, and Wei Wang contributed to review, writing, and revision of the article.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

1. Bhutta Z, Lassi Z, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related Millennium Development Goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendation for integration into national health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance; 2010.

2. Singh P, Sachs JD. 1 million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa by 2015. Lancet 2013;382:363–5.

3. Yamey G, Shretta R, BInka F. The 2030 sustainable development goal for health: must balance bold aspiration with technical feasibility. Br Med J 2014;349:5295.

4. Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J,et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(2):CD010414.

5. WHO. Strengthening the performance of community health workers in primary health care. Report of a WHO study group.World Health Organization technical report series 780. Geneva,World Health Organization; 1989.

6. Christopher J, Le M, Lewin S, Ross D. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: a systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health 2011;9:27.

7. Alam K, Tasneem S, Oliveras E. Performance of female volunteer community health workers in Dhaka urban slums. Soc Sci Med 2012;75(3):511–5.

8. Scott K, Shanker S. Tying their hands: institutional obstacles to the success of the ASHA community health worker programme in rural northern India. AIDS Care 2010;22(2):1606–12.

9. O’Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers. Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6, Suppl 1):262–9.

10. Balcazar H, Rosenthal E, Brownstein J, Rush C,Matos S, Hernandez L. Community health workers can be a public health force for change in the United States: three actions for a new paradigm. Am J Public Health 2011;101(12):2199–203.

11. Tulenko K, Mogedal S, Afzal M, Frymus D, Oshin A, Pate M,et al. Community health workers for universal health-care coverage: from fragmentation to synergy. Bull World Health Organ 2013;9:847–52.

12. Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:399–421.

13. Frymus D, Kok M, de Koning K, Quain E. Community health workers and universal health coverage: knowledge gaps and a need based global research agenda by 2015. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance/World Health Organization; 2013.

14. Global Health Workforce Alliance. Community health workers and other front line health workers: moving from fragmentation to synergy to achieve universal health coverage. Geneva: WHO;2013.

15. Naimoli J, Frymus D, Quain E, Roseman E. Community and formal health system support for enhanced community health worker performance: A U.S. Government evidence summit, final report. Washington, DC: USAID; 2012.

16. Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: what do we know about them? Geneva: World Health Organization, Evidence and Information for Policy, Department of Human Resources for Health; 2007. pp. 1–34.

17. Martinez J, Ro M, Villa NW, Powell W, Knickman JR. Transforming the delivery of care in the post-health reform era: what role will community health workers play? Am J Public Health 2011;101(12):1–5.

18. Earth Institute. One million community health workers: Technical Task Force report (2011) Earth Institute, Colombia University.www.millenniumvillages.org/uploads/ReportPaper/1mCHW_TechnicalTaskForceReport.pdf.

19. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Community health workers: a review of program evolution, evidence effectiveness and value, and status of workforce development in New England [Final report July, 2013]. www.chwcentral.org/sites/default/files/CHW-Final-Report-07-26-MASTER.pdf.

20. Crummer MB, Carter V. Critical pathways – the pivotal tool.J Cardiovasc Nurs 1993;7(4):30–7.

21. Allen CG, Escoffery C, Satsangi A, Brownstein JN. Strategies to improve the integration of community health workers into health care teams: “a little fish in a big pond”. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:150199.

22. Schneider H, Hlophe H, van Rensburg D. Community health workers and the response to HIV/AIDS in South Africa: tensions and prospects. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:179–87.

23. Shankar A, Asrilla Z, Kadha J, Sebayang S, Apriatni M,Sulastri A, et al. Programmatic effects of a large-scale multiplemicronutrient supplementation trial in Indonesia: using community facilitators as intermediaries for behavior change. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30:S207–14.

24. Amare Y. Non- financial incentives for voluntary community health workers: a qualitative study. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., The Last Ten Kilometers Project; 2009. www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id511053&lid53.

25. Altobelli L, Espejo L, Cabrejos J. Cusco, Peru: child and maternal health impact report. In: NEXOS: promoting maternal and child health linked to co-management of primary health care services. Lima: Future Generations; 2009.

26. Kane S, Gerretsen B, Scherpbier R, Dal Poz M, Dieleman M.A realist synthesis of randomised control trials involving use of community health workers for delivering child health interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:286.

27. Greenspan JA, McMahon SA, Chebet JJ, Mpunga M, Urassa DP,Winch PJ. Sources of community health worker motivation: a qualitative study in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:52.

28. Rowe AK, de Savigny D, Lanata CF, Victora CG. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? Lancet 2005;366:1026–35.

29. Hirschhorn LR, Baynes C, Sherr K, Chintu N, Awoonor-Williams JK, Finnegan K, et al. Approaches to ensuring and improving quality in the context of health system strengthening: a crosssite analysis of the five African Health Initiative Partnership programs. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13(2):8.

30. Roberton T, Applegate J, Lefevre AE, Mosha I, Cooper CM,Silverman M, et al. Initial experiences and innovations in supervising community health workers for maternal, newborn, and child health in Morogoro region, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:19.

31. Mkumbo E, Hanson C, Penfold S, Manzi F, Schellenberg J.Innovation in supervision and support of community health workers for better newborn survival in southern Tanzania. Int Health 2014;6(4):339–41.

32. Ruwoldt P, Hassett P. Zanzibar health care worker productivity study: preliminary study findings. NC, Capacity Project: Chapel Hill; 2007.

33. International Council of Nurses. Nurse retention and recruitment:developing a motivated workforce. Geneva: ICN/WHO; 2005.

34. Dieleman M, Harnmeijer JW. Improving health worker performance: in search of promising practices. WHO Department of Human Resources for Health: Geneva; 2006.

35. Prasad BM, Muraleedharan VR. Community health workers:a review of concepts, practice and policy concerns. CREHS:London; 2007.

36. Mangham-Jefferies L, Mathewos B, Russell J, Bekele A. How do health extension workers in Ethiopia allocate their time? Hum Resour Health 2014;12:61.

37. Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community health workers and mobile technology: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 2013;8:65772.

38. Brunie A, Wamala-Mucheri P, Otterness C, Akol A, Chen M,Bufumbo L, et al. Keeping community health workers in Uganda motivated: key challenges, facilitators, and preferred program inputs. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2(1):103–16.

39. Teklehaimanot A, Kitaw Y, Yohannes A, Girma S, Seyoum S,Desta H, et al. Study of the working conditions of health extension workers in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2007;21:240–5.

40. Daniels K, Clarke M, Ringsberg KC. Developing lay health worker policy in South Africa: a qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:8.

41. Nanyongo A, Nakirunda M, Makumbi F, Tomson G,K?llander K; inSCALE Study Group. Community acceptability and adoption of integrated community case management in Uganda. Am J Trop Med and Hyg 2012;87:97–104.

42. Puett C, Alderman H, Sadler K, Coates J. ‘Sometimes they fail to keep their faith in us’: community health worker perceptions of structural barriers to quality of care and community utilisation of services in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutri 2013;11:1011–22.

43. Maes K, Closser S, Kalofonos I. Listening to community health workers: how ethnographic research can inform positive relationships among community health workers, health institutions, and communities. Am J Public Health 2014;104:5–9.

44. Juma PA, Owuor K, Bennett S. Integrated community case management for childhood illnesses: explaining policy resistance in Kenya. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:65–73.

45. Rowe SY, Kelly JM, Olewe MA, Kleinbaum DG, McGowan JE Jr, McFarland DA, et al. Effect of multiple interventions on community health workers’ adherence to clinical guidelines in Siaya district, Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2007;101:188–202.46. Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K,Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database System Rev 2010;(3):CD004015.

47. Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JEW, Kane SS,Ormel H, et al. Which intervention design factors in fluence performance of community health workers in low- and middleincome countries? Health Policy Plan 2015;30(9):1207–27.

48. Dixon-Woods M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Med 2011;9:39. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3095548/pdf/1741-7015-9-39.pdf.

49. Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S,et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet 2007;369:2121–31.

50. ERT1: Final report of evidence review team 1. Which community support activities improve the performance of community health workers? US Government Evidence Summit: Community and Formal Health System Support for Enhanced Community Health Worker Performance; Washington, DC; 2012.

51. ERT3: Final report of evidence review team 3. Enhancing community health worker performance through combining community and health systems approaches. US Government Evidence Summit: Community and Formal Health System Support for Enhanced Community Health Worker Performance; Washington,DC; 2012.

52. CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: making sense of evidence about clinical effectiveness. 2010. www.casp-uk.net/.

1. School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing,China

2. School of Health Sciences,Great Lakes University of Kisumu, Kenya

3. Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology,Beijing, China

4. Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Dongola, Sudan

5. Systems and Intervention Research Centre for Health,School of Medical Sciences,Edith Cowan University, Perth,WA, Australia

Wei Wang, MD, PhD, FFPH

Global Health and Genomics,School of Medical Sciences,Edith Cowan University, Joondalup WA 6027, Australia

Tel.: +61-8-63043717

Fax: +61-8-63042626

E-mail: wei.wang@ecu.edu.au

22 December 2015;

Accepted 8 January 2016

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年1期

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年1期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Implementation of a novel train-the-trainer program for pharmacists in China

- Report on the International Symposium on Suboptimal Health Status,Inner Mongolia

- A resident’s perspective on why global health work should be incorporated into family medicine residency training

- Traditional knowledge in HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention program in northern Uganda

- Conversations in accountability: Perspectives from three charities

- Editorial