Toward a Theoretical Framework for Researching Second Language Production

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Various theories have been proposed to account for second language production and the systematic variation characteristic of such production. Most of these theories, however, constitute only partial explanations because they often fail to handle mixed empirical findings about factors held to affect second language output and underlie systematic variation. This paper proposes a new theoretical framework for posing and addressing research questions about second language production in general and systematic variation in particular. Building on influential cognitive models of second language learning and use, the theoretical framework comprises three cognitive dimensions, viz. knowledge representation, attentional focus, and processing automaticity, which interact with each other. The theoretical framework is justified by drawing on the cognitive literature and cumulative findings from second language acquisition (SLA) research. The paper also outlines possible applications of the framework to issues of interest to SLA researchers working on a number of different fronts.

Keywords: attention, automaticity, knowledge representation, models of second language learning and use, second language production, systematic variation of second language output

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Guangwei Hu, English Language & Literature Academic Group, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616. Email: guangwei.hu@nie.edu.sg

INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of Swain’s (1985) Comprehensible Output Hypothesis, there has been a sustained interest in second language (L2) production as a learning mechanism (de Bot, 1996; Gass & Mackey, 2006; Izumi & Bigelow, 2000; Muranoi, 2007; Robinson, 2005; Shehadeh, 1999; Swain, 2005; Swain & Lapkin, 1995). To gain insight into oral and written L2 output as a learning mechanism, however, it is necessary to develop a fuller understanding of the psycholinguistic processes involved in L2 production. A useful point of departure for research aimed at unveiling these processes is an inquiry into the systematic variation that characterizes L2 output (i.e., synchronically patterned variability in the L2 learner’s output that obtains under different conditions and across different contexts of language use). Such systematic variation can manifest itself in the accuracy, complexity, fluency, and appropriacy of the L2 learner’ oral and written production (Ellis, 2009e; Gilabert, 2007; Housen & Kuiken, 2009; Larsen-Freeman, 2009; Ong & Zhang, 2013; Pallotti, 2009).

Variable L2 production is an extensively documented phenomenon in second language acquisition (SLA) research. Although there is considerable evidence that systematic variation is not a unitary cognitive phenomenon (see Ellis, 2003; Skehan, 2009; Tarone, 1988), it is not entirely clear what cognitive factors are responsible for it. Empirical inconsistencies abound in this regard. Take variation in the linguistic accuracy of L2 output for example. Some studies (Hu, 2002a; Hulstijn & Hulstijn, 1984; Sorace, 1985) found distinct patterns of accuracy associated with differently represented knowledge (i.e., explicit vs. implicit knowledge), but others (Alderson, Clapham, & Steel, 1997; Elder, Warren, Hajek, Manwaring, & Davies, 1999; Grigg, 1986; Seliger, 1979) failed to find significant relationships between explicit knowledge and L2 performance or proficiency. Some studies witnessed more accurate performance on form-focused tasks (Green & Hecht, 1992) or more cognitively complex tasks (Kuiken & Vedder, 2007; Robinson, 1995; Robinson, Cadierno, & Shirai, 2009), whereas others reported greater accuracy on more communicative tasks (Leeman,etal., 1995; Liceras, 1987) or less complex tasks (Hu, 1999; Skehan & Foster, 1999). To further complicate the issue, there were also studies (e.g., Stokes, 1985; Tarone, 1988) which identified different, even opposite, patterns of variation for different target structures on the same production tasks. If one thing is clear from the research cited above, it is that research on the systematic variation of L2 output needs to move beyond hypotheses focusing on a single factor, be it monitoring, attentional focus, or cognitive complexity. Rather, such variation should be studied within a broader and more dynamic psycholinguistic framework of L2 production which can accommodate the interactions among various contributory factors.

This paper proposes an integrated theoretical framework for posing and addressing research questions about L2 production in general and its systematic variation in particular. It first discusses two psycholinguistic models of language production—Bialystok’s Analysis and Control Model and McLaughlin’s Information Processing Model—which inform the theoretical framework presented herein. It then presents and justifies the theoretical framework, drawing on the relevant literature in cognitive psychology as well as findings from SLA research. Finally, it outlines how the theoretical framework may serve as a point of departure for integrating some hitherto isolated constructs in SLA research and for exploring issues of interest to SLA researchers working on a number of different fronts. For ease and clarity of exposition, the discussion of the framework focuses on systematic variation in the linguistic accuracy of L2 learner production in both the oral and the written mode, with the understanding that accuracy is not independent of, but interacts with, complexity, fluency, and appropriacy of L2 output (Ellis, 2009e; Larsen-Freeman, 2009; Norris & Ortega, 2009; Skehan, 2009). However, it can be argued that the cognitive constructs and their interrelationships proposed in the framework to account for systematic variation in accuracy can also adequately address other dimensions of systematic variation and their interplay.

BIALYSTOK’S ANALYSIS AND CONTROL MODEL

Since the early 1980s, Ellen Bialystok has been developing a psycholinguistic model of language learning and use represented in terms of two intersecting dimensions. These dimensions were first introduced as theanalyzedandautomaticfactors in Bialystok (1982), then reformulated as the continua ofknowledgeandcontrolin Bialystok and Ryan (1985), and more recently reconceptualized asanalysisandcontrol(Bialystok, 1990a, 1990b, 1994). The following discussion is based on Bialystok (1990a, 1993, 1994), as they contain detailed presentations of the latest formulation.

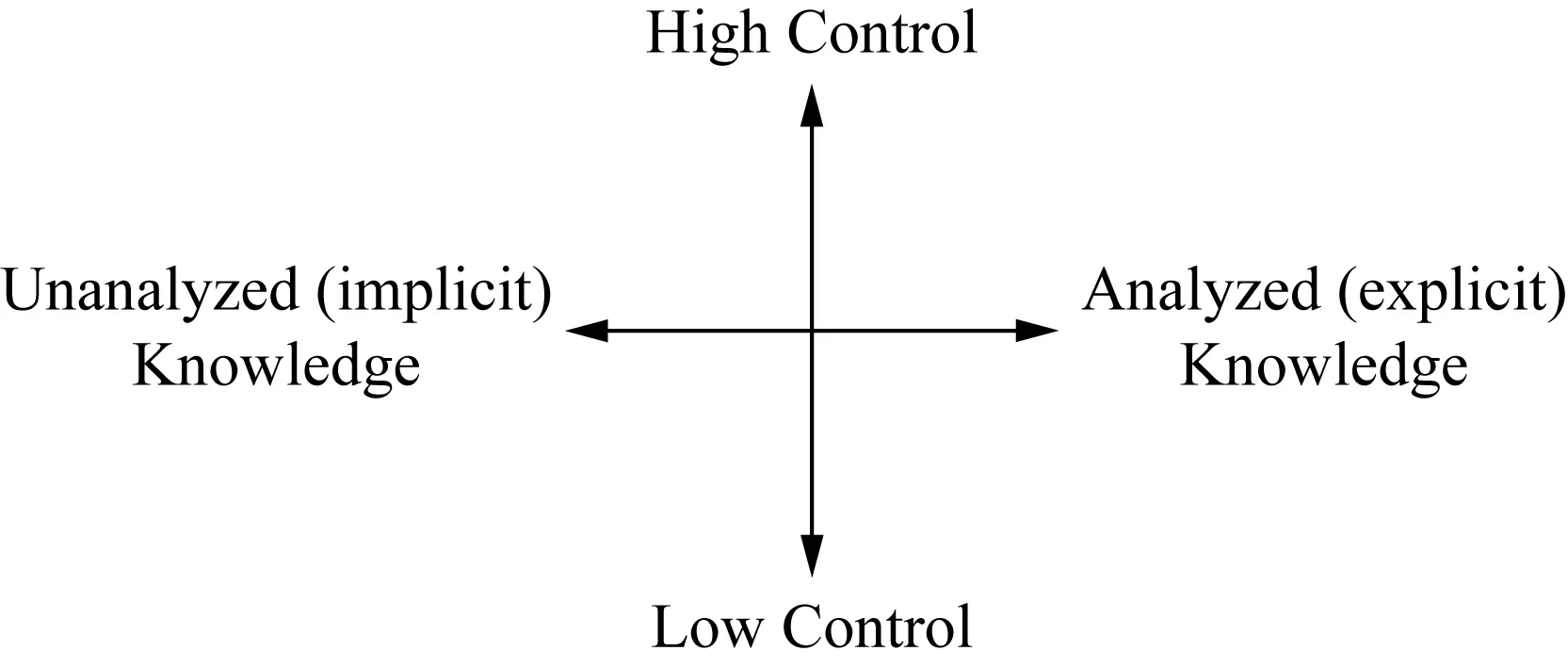

The fundamental assumption of Bialystok’s model is that language proficiency is not a unitary cognitive construct (Bialystok, 1990a). Her dissatisfaction with Anderson’s (1983) conflation of knowledge and cognitive control of knowledge in a single distinction betweendeclarativeandproceduralknowledgehas led her to maintain that “an adequate description of language proficiency requires specification of at least two components of that process” (1990b, p. 48). These two basic components areanalysisof linguistic knowledge andcontrolof linguistic processing. As shown in Figure 1, they constitute the axes along which language learning and use vary. Analysis is “the process by which mental representations that were loosely organized around meanings... become rearranged into explicit representations that are organized around formal structures” (1994, p. 159). In other words, analysis has to do with the abstractness and generality of the knowledge in question. The benefit of increasing analysis is a gain in the accessibility of the knowledge that has been analyzed. According to Bialystok (1990b), language learning starts with unanalyzed (implicit) knowledge, which gradually evolves into analyzed (explicit) knowledge through continuous and progressive analysis. Moving away from her early conceptualization (see Bialystok, 1981) of the developmental relationship between implicit and explicit knowledge, Bialystok now maintains that implicit knowledge can become explicit but the reverse does not hold. Furthermore, Bialystok contends that although the explicitness of knowledge is an indicator of the level of its mental organization, explicit knowledge is not to be confused with conscious knowledge. “The highest level of analysis of knowledge is associated with... consciousness, but consciousness is not criterial to greater levels of analysis” because “a criterion of consciousness seriously underestimates the level of analysis with which linguistic knowledge is represented” (Bialystok, 1990a, p. 122).

Figure 1 Language Use as a Function of

Control is defined as “the process of selective attention that is carried out in real time” (Bialystok, 1994, p. 160). Different from her earlier definition of control as the relative ease and rapidity with which linguistic knowledge can be accessed in actual use, the construct in the latest version refers to “the processing choice about where attention should best be spent in the limited-capacity system” (Bialystok, 1990a, p. 122). Since in real-time language processing there are multiple sources of information competing for attention, effective processing requires “the ability to control attention to relevant and appropriate information and to integrate those forms in real time” (p. 125). As their control develops, learners are more capable of executing their intentions and directing their performance in response to task demands. Thus, a selective allocation of attention is criterial to higher levels of control. Fluency or automatic performance is “an emergent property of high levels of control” (p. 122). An important developmental consequence of increasing control isintentionalprocessing, which is held to be necessary for successful performance. Another point stressed by Bialystok is that the process of selective attention and the process of knowledge analysis develop independently. “Control processes, that is, are required to retrieve any knowledge, whether analyzed or nonanalyzed; and the development of this focusing and retrieval mechanism proceeds separately and in response to different experiences than does the development of analyzed representations of knowledge” (Bialystok & Ryan, 1985, p. 216).

Although the model is intended to cover both language acquisition and use, it runs into difficulties as an account of L2 development (see Hulstijn, 1990; Schmidt, 1992). To begin with, although the postulated independence of analysis and control is justified at the level of product, in the sense that a high level of control does not necessarily imply a corresponding high level of analysis or vice versa (DeKeyser, 2003), it does not seem to be tenable in its strong form from a developmental point of view. Gombert (1990, p. 179) argues that “the analysis of knowledge must necessarily occur at an earlier level of development than the aspect of control, since the awareness of the structural characteristics of language is a prerequisite for their deliberate integration into the subject’s control of his or her activities of linguistic processing.” There are also other problems with the model as a developmental account of L2 acquisition. The claim that the acquisition of a language, be it an L1 or an L2, must start with unanalyzed (implicit) knowledge is certainly at variance with what happens in many an L2 classroom. Besides, the conceptualization of the development of control as an increasing ability to attend selectively, though plausible in the context of L1 acquisition, does not seem to fare well with L2 acquisition (Hu, 1999). Many L2 learners, especially adolescent and adult learners, are certainly able to, and have to, engage in intentional processing from the very beginning (Schmidt, 1990). It appears that these L2 learners’ problem is not so much a lack of ability to attend selectively in L2 learning. Rather, what they have to grapple with is an inadequate knowledge base of the target language as well as a lack of automaticity in accessing and applying their newly internalized knowledge (DeKeyser, 2007a).

To claim that the model is not adequately equipped as an account of L2 learning, however, is not to deny its value as a plausible explanation of L2 performance. In fact, it can serve as a starting point for a viable psycholinguistic description of L2 learners’ proficiency and performance at a given point of development. The interactions of knowledge representation and selective attention with task demands can account for a large portion of the variation manifested in L2 learners’ performance on different tasks (Bialystok, 1982; Hu, 1999, 2002a). As Bialystok (1990a) argues, “the demands imposed upon language learners by various language uses can be described more specifically in terms of the demands placed upon each of these processing components, and the proficiency of learners can be described more specifically by reference to their mastery of each of the components” (p. 117). Useful work on the relationship between differently represented knowledge and language use can be found in Bialystok (1982, 1993) and Hu (1999, 2002a).

The model, however, is incomplete in that an important dimension,automaticity, which figures prominently in most accounts of cognitive processes (Segalowitz, 2003), is notably missing. Bialystok’s (1990a) own justification for its exclusion is that it is “relatively inaccessible to investigation,” “impervious to development” ( p. 118), and “epiphenomenal” in the sense that it is only “an outcome of levels of attentional allocation” (Bialystok, 1990b, p. 50). More recent studies by DeKeyser (1997) and Robinson (1997) and research cited in Anderson (1995, Chapter 9) clearly show that automaticity is accessible to investigation and can be developed. To be sure, automaticity is developmentally related to analysis and attention in important ways, but it is also distinct from them synchronically and is certainly not epiphenomenal, inasmuch as automatic processing does not necessarily imply high levels of analysis of knowledge or absence/presence of selective attention (DeKeyser & Juffs, 2005; Ellis, 2009a). Automaticity refers to the relative ease and efficiency with which the knowledge that is needed can be accessed in real-time production (DeKeyser & Juffs, 2005; Jiang, 2012). It can be argued that it is not the reduction of attention that creates the impression of automaticity, but the automaticity of processing that makes the reduction possible (Hu, 1999). More importantly, as Faerch and Kasper (1986, pp. 53-54) point out, the conflation of processing modes and selective attention renders it impossible to investigate “how a procedure (e.g., as involved in establishing a syntactic plan) is used by different learners under different conditions.” In this light, automaticity, though interrelated with attention in complex ways, describes a different category of processing and should be kept separate from attention. Its interactions with knowledge and attention may hold the answer to much of systematic variation in L2 production that has a psycholinguistic origin (Hu, 1999).

MCLAUGHLIN’S INFORMATION-PROCESSING MODEL

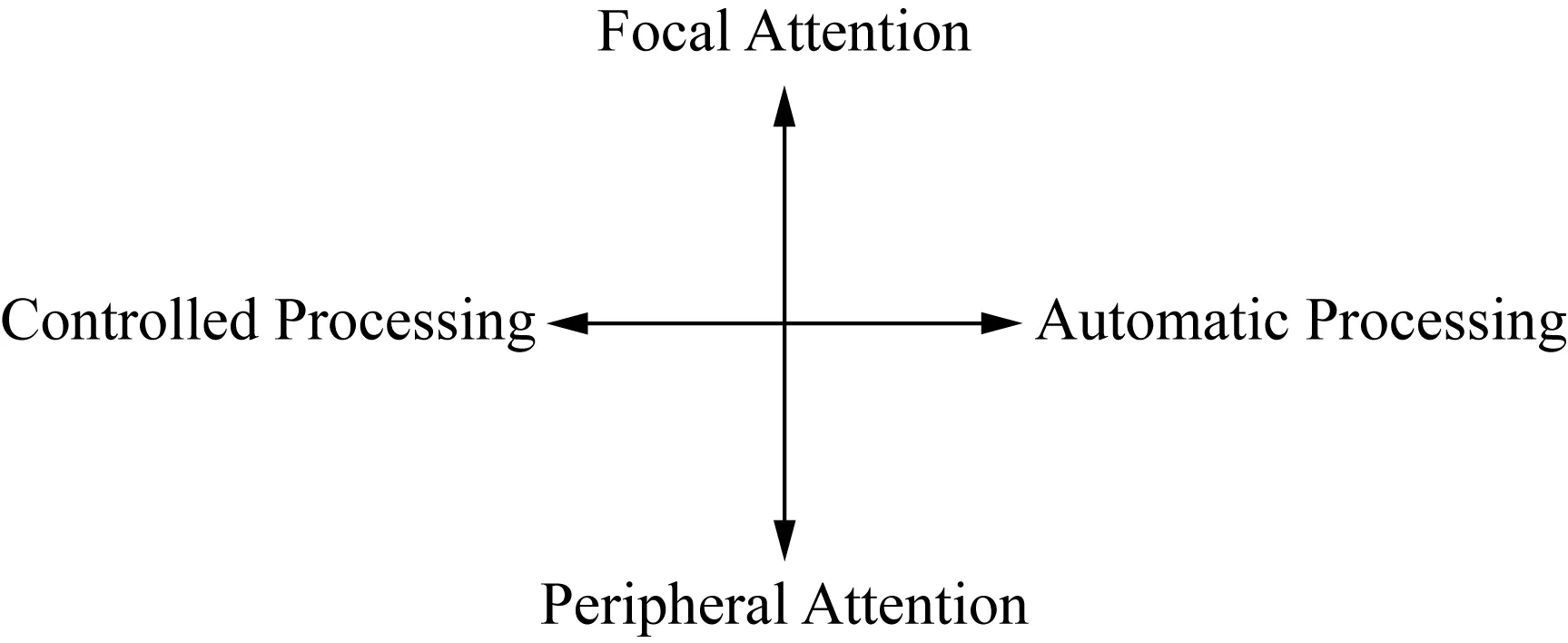

McLaughlin (1987, 1990; McLaughlin, Rossman, & McLeod, 1983) has developed a cognitive model of L2 acquisition and use that draws on theories and research about human learning and information-processing in cognitive psychology (e.g., Cheng, 1985; Posner & Snyder, 1975; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Fundamental to the model is the notion that “humans are limited-capacity information processors, both in terms of what they can attend to at a given point in time and in terms of what they can handle on the basis of knowledge and expectations” (McLaughlinetal., 1983, p. 137). The processing limitations that humans have to grapple with are perceived to exist along two independent dimensions that intersect:focusofattentionandautomaticityofprocessing.

The first dimension, very much similar to thecontroldimension of Bialystok’s model, is a continuum of attentional allocation ranging from highly peripheral to highly focal attention. The focus of attention is characterized by selectivity and is largely a function of a particular task configuration and the limited human capacity to handle information. On this view, attention is a limited-capacity system of cognitive resources which is deployed to regulate the influx of information and select relevant information for further processing operations, depending on specific goals and plans. Thus, in accomplishing a complex task such as communication in an L2, a learner necessarily selects some task components to focus attention on but attends to the rest only peripherally in accordance with task demands and as a consequence of processing limitations. Similarly, in learning a complex skill, “subtasks need to be integrated by a ‘plan’ whereby the selection of subactivities is regulated according to overriding goals... [and]... attention is given to various subtasks on a time-sharing basis, with the learner attending first to one subtask and then to another” (McLeod & McLaughlin, 1986, p. 109).

The second dimension of the model is a continuum of information-processing modes ranging from highly controlled to highly automatic processing with many gradations falling in between. Following Shiffrin and Schneider (1977), controlled processing is

... a temporary activation of nodes [i.e., sets of informational elements in human memory] in a sequence. This activation is under the attentional control of the subject and, since attention is required, only one such sequence can normally be controlled at a time without interference. Consequently, controlled processes are thought to intrude on the ability to perform simultaneously any other task that also requires a capacity investment. Controlled processes are therefore tightly capacity-limited, but have the advantage of being relatively easy to set up, alter, and apply to novel situations. (McLeod & McLaughlin, 1986, p. 110)

By contrast,

automaticprocessinginvolves the activation of certain nodes in memory every time the appropriate inputs are present. This activation is a learned response that has been built up through the consistent mapping of the same input to the same pattern of activation over many trials. Since an automatic process utilizes a relatively permanent set of associative connections in long-term storage, most automatic processes require an appreciable amount of training to develop fully. Once learned, an automatic process occurs rapidly and is difficult to suppress or alter. (McLaughlin, 1987, p. 134)

On this view, controlled processing involves deliberate choices and combinations of informational elements, operates slowly and sequentially, and consumes much processing capacity. Automatic processing, on the other hand, is fast, effortless, and light on attentional resources, thus leaving more attention available for use by controlled processes being carried out simultaneously on other task components. Learning involves a progression from controlled to automatic processing. “Complex skills are learned and routinized (i.e., become automatic) only after the earlier use of controlled processes... that regulate the flow of information from working to long-term memory” (McLeod & McLaughlin, 1986, p. 111). Automaticity is achieved largely through practice. However, automaticity involves more than the frequency with which a certain procedure is activated: It also interacts with the restructuring of knowledge (McLaughlin, 1990). Successful performance depends on an optimal allocation of processing resources and a flexible balance between automatic and controlled processing. Figure 2 sums up the application of the two-dimensional model to L2 performance.

Figure 2 Performance as a Function of

The way the two dimensions intersect each other to yield four basic types of performance seems to run counter to the foregoing characterization of automatic and controlled processing. According to the model, controlled processing requires more than peripheral attention for its successful operation, and automatic processing consumes little attentional capacity. The existence of the focal/automatic and peripheral/controlled combinations in Figure 2 would prima facie contradict the tenets of the model. This contradiction, however, is not a real one. It is true that the model suggests that, under normal circumstances, automatic processing does not need focal attention and that the successful operation of controlled processing is predicated on the availability of sufficient attention. Nevertheless, it also posits that attentional allocation is under some level of cognitive control: Humans can choose to focus their attention deliberately on automatic processes or to divert it from controlled processes. In other words, attention is subject to voluntary control and can be directed by internal intentions (Schmidt, 2001). Therefore, theoretically speaking, “controlled and automatic processes can be either the focus of attention (which is usually, but not always, true of controlled processes) or on the periphery of attention (which is usually, but not always, true of automatic processes)” (McLaughlinetal., 1983, p. 142).

The model, as outlined above, gives a plausible explanation for variable L2 performance under certain conditions of language use (see Hu, 2002a; Hulstijn & Hulstijn, 1984; Lehtonen, 1990; Segalowitz, 1986). However, the model is far from comprehensive and, consequently, its explanatory power suffers. In particular, it fails to include aknowledgedimension which has been found by Bialystok and others (e.g., DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis, 2004, 2005; Hu, 2002b) to play an important role in L2 use. McLaughlin himself came to see this weakness when he attempted to use the model to account for the findings of a reading study (McLeod & McLaughlin, 1986). Since then, he has introduced a new construct into his model:restructuring. Drawing on work done by cognitive psychologists (Cheng, 1985; Karmiloff-Smith, 1986b), McLaughlin (1990, p. 113) sees restructuring as the process whereby “l(fā)earners reorganize their internal representational framework.” Restructuring allows learning to occur in a discontinuous fashion, involves the replacement of old components with new ones, and brings about decrements as well as improvements in performance. Though potentially useful in explaining diachronic variation in L2 use, the notion of restructuring cannot easily be related to the two-dimensional model discussed above. As the following section shows, however, the inclusion of a knowledge dimension in a model of L2 performance is justifiable and presents important advantages.

KNOWLEDGE, ATTENTION, AND AUTOMATICITY: A 3-DIMENSIONAL FRAEMWORK

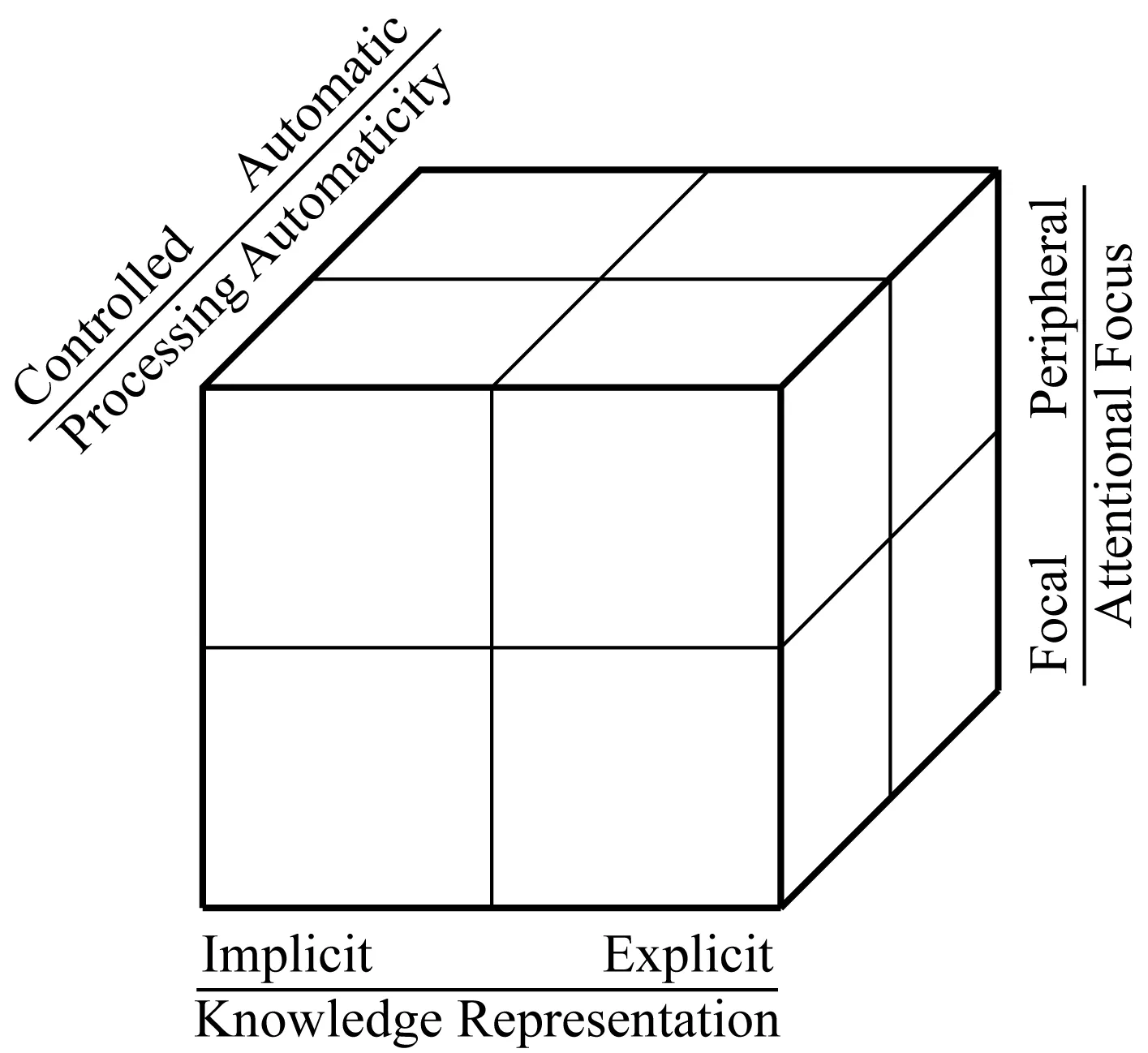

It was argued in the previous sections that both Bialystok’s Analysis and Control Model and McLaughlin’s Information-Processing Model constitute only partial explanations of L2 production. Given their respective strengths and because of their complementarity, however, an integration of the two models should yield a more comprehensive framework for researching L2 performance in general and systematic variation in particular. The theoretical framework to be outlined in this section represents an endeavor to this end. As will become clear, such an integration is not unwarranted but can produce a more powerful theoretical framework within which empirical work can be carried out. It not only overcomes the limitations of the original models but also addresses a theoretical impasse that Ellis (2009d) identifies in relation to current attempts to conflate knowledge and automaticity into a single dimension of controlled explicit knowledge vs. automatic implicit knowledge. As Ellis notes, one consequence of such a conflation is that researchers are often compelled to “invoke additional characteristics of the two types of knowledge (e.g., awareness and focus on meaning/form)” and/or further characteristics of processing such as “online or offline processing” (p. 342) to make unwieldy distinctions that detract from the usefulness of the construct.

The theoretical framework proposed here, as schematically represented in Figure 3, comprises three dimensions:knowledgerepresentation,attentionalfocus, andprocessingautomaticity. These dimensions are continua rather than dichotomies, in keeping with their original treatment in the two models as well as with research in the fields of cognitive psychology and SLA research (Bialystok, 1990b, 1993; DeKeyser, 1997; Dienes & Perner, 1999; Faerch & Kasper, 1987; Hu, 2002b; Karmiloff-Smith, 1986a; McLaughlin, 1987; Segalowitz, 2003; Tarone, 1988). The three dimensions intersect one another and form, so to speak, the space within which L2 production and its systematic variation occur. Knowledge representation forms a continuum ranging from implicit to explicit knowledge, depending on the level of explicitness with which knowledge is represented. Since the highest level of explicitness is associated with consciousness (Bialystok, 1990a) and because metalinguistic knowledge is more or less consciously represented and verbalizable knowledge about the target grammar (Ellis, 2009a; Hu, 2011b; Roehr, 2007), such knowledge is located at the extreme explicit end of the continuum. Attentional focus refers to the allocation of attentional capacity in L2 performance, which varies from highly peripheral to highly focal attention, depending on task demands and communicative pressure (McLaughlin, 1987; Schmidt, 2001). Processing automaticity is a continuum of information-processing modes which ranges between highly controlled and highly automatic processing (DeKeyser, 1997; Segalowitz, 2003). Within the multidimensional theoretical framework, systematic variation in L2 production is a function of the interactions among knowledge representation, attentional focus, and processing automaticity required by specific production tasks.

Figure 3 Cognitive Dimensions of L2 Production

The theoretical framework can be justified on the grounds that each of its dimensions is a well established one in cognitive psychology and SLA research and that there are complex interactions among them that are increasingly understood. Although the very application of the implicit/explicit distinction to learning processes has been controversial, the distinction at the level of product (i.e., in terms of knowledge that has been internalized) is not problematic (Ellis, 2009a). Both DeKeyser (2003) and Ellis (2004) point out that the existence of implicit and explicit knowledge is widely recognized in cognitive psychology, though different terms have been used to refer to the distinction. In the cognitive literature, it is also generally accepted that how knowledge is represented can have important implications for how it is used (Anderson, 1995; Anderson & Fincham, 1994), and there is cumulative neurobiological evidence in support of the validity of the distinction (see Ellis, 2009a, 2009d). Many SLA theorists and researchers (e.g., DeKeyser & Juffs, 2005; Ellis, 2005, 2009b, c; Hu, 1999; Hulstijn, 1990; Johnson, 1996; Roehr, 2007; Sorace, 1985) have also clearly recognized the relevance and usefulness of distinguishing implicit and explicit knowledge. The distinction gives several advantages. It allows a more accurate description of what an L2 learner knows of the target language. It also allows SLA researchers to examine the relationship between what L2 learners know and what they can actually do. Furthermore, it makes it possible to investigate, in a more finely grained manner, the effects of those factors that moderate the use of L2 learners’ internalized knowledge in performance. As Odlin (1986, p. 124) argues,

without distinctions in the kinds of knowledge underlying second language performance, there is little hope of explaining what it means to ‘know another language’. And without an adequate explanation of such knowledge, discussions of the comparative value of pattern practice, grammar instruction, and other techniques in foreign language pedagogy remain largely speculative.

The importance of selective attention has also been widely recognized in cognitive sciences and SLA research. Psychologists such as Baddeley (2007), Kahneman and Treisman (1984), Logan (1988), Posner and Petersen (1990), and Wickens (1984) have all assigned an important role to attention in cognitive operations. In virtually all models of perception and fluency, crucial assumptions have been made about attention (Schmidt, 2001). In the field of language use, L1 researchers, notably Labov (1972), have identified attention as an important variable in their work on the style-shifting patterns of native speakers. Similarly, SLA theorists and researchers have emphasized and investigated the role of attention in learning (Leow, 1997; Robinson, 2003; Schmidt, 1990; Sharwood Smith, 1991; Williams, 1999) and in production (Ellis & Yuan, 2004; Ortega, 1999; Robinson, 2005; Schmidt, 1992; Skehan & Foster, 1999). Although attention is not the sole cause of systematic variation in L2 performance (see Tarone, 1988), there is growing evidence that it is one of the most important causes. Schmidt (2001) points out that “the concept of attention is necessary in order to understand virtually every aspect of second language acquisition” (p. 3) and that it is “essential to the control of action” (p. 16). Bialystok (1990b) clearly states that “information can be processed to various degrees of detail, and more fine-grained processing requires more attention” (p. 50). She also makes the point that “l(fā)earners could (and do) choose to increase attention and improve the resolution of the representation” (1990b, p. 50). In a similar vein, McLaughlinetal. (1983) point out that selective attention “is required by the limited capacity of the human mind to process information” (p. 136) and that “an adequate information-processing model of second language learning would include not only specification of how automatic and controlled processes are coordinated, but would also require an understanding of selective attention and the role and function of consciousness” (p. 155).

The distinction between controlled and automatic processing is another well-established construct in contemporary cognitive research and SLA theorizing. Anderson (1995), Ericsson and Simon (1993), Fisk and Schneider (1984), LaBerge (1975), Logan (1988), Shiffrin and Dumais (1981), and Shiffrin and Schneider (1977) have all made extensive use of this distinction in accounting for how information is typically processed by the human mind. There is substantial empirical support for the distinction from research carried out in areas of visual search, category learning, lexical retrieval, syntactic processing, reading and verbal reporting. Brain imaging research has also pointed to separate neural circuits for controlled and automatic processing (see Segalowitz, 2003). Informed by the work of cognitive scientists, many SLA researchers have also made reference to the controlled/automatic distinction in their theoretical discussions of, and empirical investigations into, L2 acquisition and performance (e.g., DeKeyser, 1997, 2007a; Hu, 2002a; Jiang, 2012; Johnson, 1996; Skehan & Foster, 1999; Towell, Hawkins, & Bazergui, 1996). All this research recognizes the important role played by these two basic modes of information processing (Segalowitz, 2003). There is accumulating evidence that the acquisition of a cognitive skill starts with controlled processing and gradually moves toward more automatic processing which can overcome information-processing limitations by reducing the burden on cognitive resources (Hu, 2002b). It is certainly true to say that McLaughlinetal. (1983) and McLaughlin (1987) heralded this growing interest among SLA researchers in the role of processing automaticity in L2 learning and performance. Although Bialystok has excluded the notion of automaticity from the latest version of her model, the early versions (Bialystok, 1982; Bialystok & Ryan, 1985) did include automaticity as an independent dimension or a component of the control dimension. On one occasion, she argued that it is “reasonable to separate the learner’s representation of knowledge from access to that knowledge and that each of these variables contributes to the learner’s control over that knowledge” (Bialystok, 1988, p. 36).

In line with findings from cognitive and SLA research as well as theorizing by Bialystok and McLaughlin, the following assumptions underlie the framework. First, explicit knowledge is acquired as analyzed knowledge and stored in long-term memory as a database which can be accessed through general interpretative procedures, whereas implicit knowledge is acquired as specialized procedures for action (Anderson, 1983; Ellis, 2009a). Explicit knowledge is generative, in that it can be used in both familiar and novel contexts (DeKeyser, 2003; Johnson, 1996). It can be easily modified or replaced with new information. However, it takes much time and practice to proceduralize and automatize access to such knowledge (Anderson, 1982; DeKeyser, 2007a, 2007b; McLaughlin, 1987). Implicit knowledge, on the other hand, can quickly become appreciably automatized because it is internalized in an already proceduralized form (Johnson, 1996). As a result, it is procedure-specific and cannot be easily modified or suppressed. Second, attention is selective, partially subject to voluntary control, and essential to action control (Bialystok, 1994; Leow, 1997; McLaughlinetal., 1983; Ortega, 1999; Schmidt, 2001). The most fundamental attribute of attention is its limited capacity. Although psychologists disagree about whether there is only a single attentional resource (Shiffrin, 1976) or there exist multiple attentional resources (Wickens, 1984), it is generally accepted that each resource pool has its capacity limitations (Schmidt, 2001). Finally, controlled processing is performed in a relatively slow, laborious, and serial manner that allows greater control of the relevant information by the performer and easier adaptation to new situations (McLaughlin, 1987). However, it is heavy on processing capacity. Automatic processing, on the other hand, is a more efficient, specialized, and routinized mode of processing that requires little processing capacity and does not interfere with the simultaneous execution of other capacity-taxing processes (Segalowitz, 2003; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Automatic processing occurs only when the information in question has been activated some criterion number of times and has achieved some threshold of strength (Anderson, 1983; DeKeyser, 1997, 2007a). Furthermore, an automatic process is difficult to modify or replace, and may become the default option when attentional pressure is present (Faerch & Kasper, 1987; McLaughlin, 1987; Segalowitz, 2003).

UTILITIY OF THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

To be sure, the three dimensions incorporated into the theoretical framework of L2 performance are not new ones, but the way they are perceived to interact with one another and to affect L2 performance systematically through their interactions cut the pie of L2 production and systematic variation in a different manner. Importantly, links and interactions that were missing from previous theorizing on L2 performance but that would seem to merit serious consideration have been proposed and justified. This reformulated account of L2 performance can serve as a useful framework for posing and addressing certain research questions about psycholinguistic processes involved in L2 performance, systematic variation in L2 production, and constraints on access to differently represented knowledge in real time.

The theoretical framework and its underlying assumptions can generate specific hypotheses for empirical testing. One hypothesis is that there are distinct patterns of formal accuracy associated with differently represented knowledge (i.e., explicit and implicit knowledge) of an L2 on specific production tasks. For if explicit and implicit knowledge are internalized and represented in different ways, it is reasonable to predict that they differ in terms of real-time accessibility at a given point of L2 development, especially at lower stages. Such differences in accessibility can be expected to give rise to differences in the extent to which these two types of knowledge are mobilized on a specific production task (Hu, 1999). A second hypothesis is that the patterns of formal accuracy associated with explicit and implicit knowledge may vary to different extents across production tasks that differ in attentional configurations. In other words, access to different types of knowledge in real-time production differs in their susceptibility to the influence of differences in attentional focus between various production tasks (Hu, 2002a). If explicit and implicit knowledge are accessed in different processing modes at a given point in time, they can be expected to depend, to different extents, on the availability of attentional resources for successful processing. Given the assumption underlying controlled and automatic processing, a third hypothesis predicts that regardless of the explicitness of the knowledge in question, formal accuracy associated with more automatized knowledge will be less affected by attentional pressure than formal accuracy associated with less automatized knowledge (Hu, 2002b). That is, the extent to which attentional configurations on specific tasks constrain the involvement of a knowledge source may depend on the level of automaticity reached in processing the knowledge in question. Other specific hypotheses can also be derived from the theoretical framework. For example, time pressure built into a production task can have a differential effect on the involvement of knowledge sources that differ in terms of processing automaticity, and cognitively demanding tasks may inhibit access to unautomatized explicit knowledge by leaving little attentional capacity available for the operation of controlled processing. Although the above hypotheses are concerned with formal accuracy, specific hypotheses can also be framed with regard to other performance measures such as fluency and linguistic complexity of production (see Ellis, 2009e; Skehan, 2009).

The theoretical framework is not only aimed at uncovering the primary cognitive factors involved in L2 performance and the cardinal dimensions of its systematic variation but it is also intended to explain how other factors may affect L2 production. Figure 4 presents an expanded view of how various contextual, pedagogical, linguistic, and individual factors may influence L2 production via the three fundamental dimensions of L2 production. Some of these factors are task structure (Skehan & Foster, 1999), discourse contexts (Robinson, 1995), modality of language use (Elder & Ellis, 2009), time pressure (Hu, 2002b), opportunity for planning (Ellis, 2009e; Ellis & Yuan, 2004), type of instruction (Erlam, Loewen, & Philp, 2009; Hu, 2011a, 2011b), transfer of training (DeKeyser, 2007a; Hu, 2010), learning environments (Philp, 2009), linguistic prototypicality (Hu, 2002b), linguistic features (Ellis, 2009c), age (DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis, 2005; Philp, 2009), working memory (DeKeyser & Koeth, 2011; Erlam, 2009), current proficiency/developmental stage (Elder & Ellis, 2009), learning/cognitive style (Zietek & Roehr, 2011), strategies for language learning/use (Hu, 1999), cross-linguistic influences (Elder & Manwaring, 2004; Hu, Skuja-Steele, & Hvitfeldt, 2000), and motivation (Ellis, 2009d). The overarching claim is that these factors come to shape L2 performance and contribute to systematic variation through the interplay among knowledge representation, attentional focus, and processing automaticity in the process of production. They can also have their effect felt by mediating the contributions of other factors to L2 learning and use.

By way of illustration, I shall examine how findings from research in two areas can be interpreted within this theoretical framework. The first area is L1 transfer. One type of L1 transfer much discussed in the SLA literature is automatic transfer (Faerch & Kasper, 1987; Sharwood Smith, 1986). It is posited that this type of transfer involves the activation of highly automatized L1 procedures in situations where linguistic processing is on the periphery of attention and where there is competition between L1 and L2 subplans of production. The study by Huetal. (2000) produced some evidence of automatic transfer. The researchers examined the accuracy with which Chinese learners of English used the English articles on a battery of production tasks which differed in terms of attention to form. They found that although the learners had correct explicit knowledge of the target uses, they frequently failed to supply the definite or indefinite article in obligatory contexts. Many of these omissions could be attributed to the influence of Mandarin Chinese, in which a noun phrase can occur without any determiner regardless of definite or indefinite reference. More importantly, an inverse relationship was found between the tendency to leave out the definite or indefinite article and the amount of attention to form allowed by the production tasks. One plausible interpretation of these results is that the attentional configurations required by the production tasks constrained the learners’ access to their explicit knowledge to different extents. On those tasks where they were under a heavy cognitive load and were preoccupied with conceptual processing, the learners tended to fall back on highly automatized procedures (L1 procedures) as a way of circumventing the attention-consuming process of activating and applying their largely unautomatized explicit knowledge. This would result in a notable decline in their accuracy in using the target structures. However, as Kohn (1986, p. 26) argues, “errors which occur as the result of a transfer on the retrieval level not backed up by the learner’s knowledge are usually not very stable” and “as soon as the output conditions are more favourable the learner will be able to use his knowledge to control for these errors with the result that they disappear.” Thus, on the production tasks that allowed a greater focus of attention on form, the learners’ suppliance of the target structures attained higher levels of accuracy most likely because of their greater opportunity to draw on their explicit knowledge.

Figure 4 An Expanded View of How Various Contextual, Linguistic,

The second area of research which can be explored within the theoretical framework concerns the effect of task structure on L2 performance. Several studies (Ellis, 2009e; Ellis & Yuan, 2004; Foster & Skehan, 1996; Huetal., 2000; Ong & Zhang, 2013; Skehan & Foster, 1999) found that different features of tasks had an impact on performance in terms of fluency, linguistic complexity, and/or accuracy. For example, Skehan and Foster (1999) explored the effect of inherent task structure on L2 performance by using structured and unstructured narrative retelling tasks administered under different processing conditions. The researchers were able to demonstrate that tasks with clear inherent structure elicited more fluent performance than those without such clear structure and that greater linguistic complexity was achieved under less demanding processing conditions. There was also a significant interaction effect between task structure and processing conditions on linguistic accuracy. Skehan and Foster interpreted their results as suggesting that those tasks with clear inherent structure eased the processing burden and allowed the participants to allocate greater attention to linguistic processing in a more sustained manner than those tasks with less clear macrostructure. Presumably, the greater allocation of attention to language form enabled access to knowledge that otherwise would have been inaccessible and facilitated processes that were carried out in a relatively controlled mode. Huetal. (2000) also attested to an effect of task structure on performance. The L2 learners in their study completed four spontaneous writing tasks: two narratives and two arguments. They were found to be significantly more accurate in using a number of target structures when they had explicit knowledge than when they had only implicit knowledge. Furthermore, they were markedly more accurate on the narrative tasks than on the argumentative ones when explicit knowledge was available. The researchers attributed the higher accuracy evidenced on the narrative tasks to the participants’ more experience with and greater expertise in narrative structure, which in turn allowed them to allocate more attention to linguistic processing and hence enabled them to access their largely unautomatized explicit knowledge.

Space constraints prevent a detailed explication of how the other factors presented in Figure 4 may be explored within the integrated theoretical framework. As with L1 transfer and task structure, however, it is not difficult to envisage links between these factors and the dimensions of the theoretical framework. For instance, L2 learners’ online choice of strategies for use may be determined by the attentional configuration required by a specific task and by their automaticity in applying the strategies in question. Similarly, differences in the mode of language use (e.g., speaking vs. writing) and time pressure may impinge on the allocation of attention to various components of the production process and consequently call for different knowledge sources and processing modes. A particular learning style or learning environment may have its impact on L2 performance by pushing the L2 learner toward one, rather than the other, end of the knowledge dimension and/or automaticity dimension. Linguistic factors such as the relative prototypicality or markedness of target uses may affect, among other things, L2 learners’ automaticity in processing their knowledge of these uses. It is noteworthy that when a factor affects any of the three dimensions, viz. knowledge representation, attentional focus and processing automaticity, there can be important repercussions for L2 learners’ development along the other dimensions and for the real-time interplay among all the dimensions in performance. In other words, there are dynamic interrelationships among these dimensions.

CONCLUSION

This paper has presented a theoretical framework for researching L2 production that integrates previous theoretical and empirical work on attentional resources, knowledge representation, and processing automaticity in cognitive psychology and SLA. The framework is based on the assumption that a comprehensive account of L2 use and its inherent systematic variability is based on an understanding of the cognitive processes that L2 learners engage in during performance. It is falsifiable in that it can generate specific and empirically testable hypotheses about how the cognitive processes may impact upon L2 production. The theoretical framework represents an attempt to integrate into a coherent conceptualization the many factors known to affect L2 production and contribute to its systematic variation. In other words, this conceptualization makes it possible to examine the impact on L2 use of many hitherto isolated factors (e.g., language learning/use strategies, cross-linguistic influences, cognitive style, and type of instruction) in an integrated framework. How these and other factors come to affect and shape the interactions of knowledge, attention, and control in the very process of L2 use are issues that need to be addressed and worked out in more detail and with greater clarity in future empirical research. Insights into L2 production yielded by such empirical research can feed back into theorizing on second language acquisition.

REFERENCES

Alderson, J. C., Clapham, C., & Steel, D. (1997). Metalinguistic knowledge, language aptitude and language proficiency.LanguageTeachingResearch, 1, 93-121.

Anderson, J. R. (1983).Thearchitectureofcognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Anderson, J. R. (1995).Learningandmemory:Anintegratedapproach. New York: Wiley.

Anderson, J. R. & Fincham, J. M. (1994). Acquisition of procedural skills from examples.JournalofExperimentalPsychology:Learning,Memory,andCognition, 20, 1322-1340.

Baddeley, A. D. (2007).Workingmemory,thought,andaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bialystok, E. (1981). The role of linguistic knowledge in second language use.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 4, 31-45.

Bialystok, E. (1982). On the relationship between knowing and using forms.AppliedLinguistics, 3, 181-206.

Bialystok, E. (1988). Psycholinguistic dimensions of second language proficiency. In W. Rutherford & M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.),Grammarandsecondlanguageteaching:Abookofreadings(pp. 31-50). New York: Newbury House.

Bialystok, E. (1990a).Communicationstrategies:Apsychologicalanalysisofsecondlanguageuse. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Bialystok, E. (1990b). The dangers of dichotomy: A reply to Hulstijn.AppliedLinguistics, 11, 46-51.

Bialystok, E. (1993). Metalinguistic dimensions of bilingual language proficiency. In E. Bialystok (Ed.),Languageprocessinginbilingualchildren(pp. 113-140). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bialystok, E. (1994). Analysis and control in the development of second language proficiency.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 16, 157-168.

Bialystok, E. & Ryan, E. B. (1985). A metacognitive framework for the development of first and second language skills. In D. L. Forrest-Pressley, G. E. Mackinnon, & T. G. Waller (Eds.),Metacognition,cognition,andhumanperformance:Vol. 1.Theoreticalperspectives(pp. 207-252). Orlando: Academic Press.

Cheng, P. W. (1985). Restructuring versus automaticity: Alternative accounts of skill acquisition.PsychologicalReview, 92, 414-423.

de Bot, K. (1996). The psycholinguistics of the output hypothesis.LanguageLearning, 46, 529-555.

DeKeyser, R. M. (1997). Beyond explicit rule learning: Automatizing second language morphosyntax.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 19, 195-221.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.),Thehandbookofsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 313-348). Malden: Blackwell.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2007a). Introduction: Situating the concept of practice. In R. M. DeKeyser (Ed.),Practiceinasecondlanguage:Perspectivesfromappliedlinguisticsandcognitivepsychology(pp. 1-18). New York: Cambridge University Press.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2007b). Conclusion: The future of practice. In R. M. DeKeyser (Ed.),Practiceinasecondlanguage:Perspectivesfromappliedlinguisticsandcognitivepsychology(pp. 287-304). New York: Cambridge University Press.

DeKeyser, R. M. & Juffs, A. (2005). Cognitive considerations in L2 learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbookofresearchinsecondlanguageteachingandlearning(pp. 437-454). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

DeKeyser, R. M. & Koeth, J. (2011). Cognitive aptitudes for second language learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbookofresearchinsecondlanguageteachingandlearning(Vol. 2, pp. 395-406). New York: Routledge.

Dienes, Z. & Perner, J. (1999). A theory of implicit and explicit knowledge.BehavioralandBrainSciences, 22, 735-808.

Elder, C. & Ellis, R. (2009). Implicit and explicit knowledge of an L2 and language proficiency. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 167-193). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Elder, C. & Manwaring, D. (2004). The relationship between metalinguistic knowledge and learning outcomes among undergraduate students of Chinese.LanguageAwareness, 13, 145-162.

Elder, C., Warren, J., Hajek, J., Manwaring, D., & Davies, A. (1999). Metalinguistic knowledge: How important is it in studying a language at university?AustralianReviewofAppliedLinguistics, 22, 81-95.

Ellis, R. (2003).Task-basedlanguagelearningandteaching. Oxford: Oxford University press.

Ellis, R. (2004). The definition and measurement of L2 explicit knowledge.LanguageLearning, 54, 227-275.

Ellis, R. (2005). Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge of a second language: A psychometric study.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 27, 141-172

Ellis, R. (2009a). Implicit and explicit learning, knowledge and instruction. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 3-25). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ellis, R. (2009b). Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge of a second language. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 31-64). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ellis, R. (2009c). Investigating learning difficulty in terms of implicit and explicit knowledge. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 143-166). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ellis, R. (2009d). Retrospect and prospect. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 335-353). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ellis, R. (2009e). The differential effects of three types of task planning on the fluency, complexity, and accuracy in L2 oral production.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 474-509.

Ellis, R. & Yuan, F. (2004). The effects of planning on fluency, complexity, and accuracy in second language narrative writing.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 26, 59-84.

Ericsson, K. A. & Simon, H. A. (1993).Protocolanalysis:Verbalreportsasdata(Rev. ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Erlam, R. (2009). The elicited oral imitation test as a measure of implicit knowledge. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 65-93). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Erlam, R., Loewen, S., & Philp, J. (2009). The roles of output-based and input-based instruction in the acquisition of L2 implicit and explicit knowledge. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 241-261). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1986). Cognitive dimensions of language transfer. In E. Kellerman & M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.),Crosslinguisticinfluenceinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 49-65). New York: Pergamon.

Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1987). Perspectives on language transfer.AppliedLinguistics, 8, 111-136.

Fisk, A. D. & Schneider, W. (1984). Memory as a function of attention, level of processing, and automatization.JournalofExperimentalPsychology:Learning,MemoryandCognition, 10, 181-197.

Foster, P. & Skehan, P. (1996). The influence of planning and task type on second language performance.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 18, 299-323.

Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A. (2006). Input, interaction and output: An overview.AILAReview, 19, 3-17.

Gilabert, R. (2007). Effects of manipulating task complexity on self-repairs during L2 oral production.InternationalJournalofAppliedLinguistics, 45, 215-240.

Gombert, J. E. (1990).Metalinguisticdevelopment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Green, P. S. & Hecht, K. (1992). Implicit and explicit grammar: An empirical study.AppliedLinguistics, 13, 168-184.

Grigg, T. (1986). The effects of task, time and rule knowledge on grammar performance for three English structures.UniversityofHawaiiWorkingPapersinESL, 5, 37-60.

Housen, A. & Kuiken, F. (2009). Complexity, accuracy, and fluency in second language acquisition.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 461-473.

Hu, G. (1999).Explicitmetalinguisticknowledgeatwork:ThecaseofspontaneouswrittenproductionbyformaladultChineselearnersofEnglish. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nanyang Technological University, Republic of Singapore.

Hu, G. (2002a). Metalinguistic knowledge at work: The case of written production by Chinese learners of English.AsianJournalofEnglishLanguageTeaching, 12, 5-44.

Hu, G. (2002b). Psychological constraints on the utility of metalinguistic knowledge in second language production.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 24, 347-386.

Hu, G. (2010). Revisiting the role of metalanguage in L2 teaching and learning.EnglishAustraliaJournal, 26, 61-70.

Hu, G. (2011a). A place for metalanguage in the L2 classroom.ELTJournal, 65, 180-182.

Hu, G. (2011b). Metalinguistic knowledge, metalanguage, and their relationship in L2 learners.System, 39, 63-77.

Hu, G., Skuja-Steele, R., & Hvitfeldt, R. (2000).IsexplicitmetalinguisticknowledgeusefulinL2production? Paper presented at the International Conference on Language in the Mind? Implications for Research and Education, Fort Canning Lodge, Singapore.

Hulstijn, J. H. (1990). A comparison between the information-processing and the analysis/control approaches to language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 11, 30-45.

Hulstijn, J. H. & Hulstijn, W. (1984). Grammatical errors as a function of processing constraints and explicit knowledge.LanguageLearning, 34, 23-43.

Izumi, S. & Bigelow, M. (2000). Does output promote noticing and second language acquisition?.TESOLQuarterly, 34, 239-278.

Jiang. N. (2012). Automaticity in a second language: Definition, importance, and assessment.ContemporaryForeignLanguages, 384, 34-48.

Johnson, K. (1996).Languageteachingandskilllearning. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Kahneman, D. & Treisman, A. (1984). Changing views of attention and automaticity. In R. Parasuraman & D. R. Davies (Eds.),Varietiesofattention(pp. 29-61). Orlando: Academic Press.

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1986a). From meta-processes to conscious access: Evidence from children’s metalinguistic and repair data.Cognition, 23, 95-147.

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1986b). Stage/structure versus phase/process in modelling linguistic and cognitive development. In I. Levin (Ed.),Stageandstructure:Reopeningthedebate(pp. 164-190). Norwood: Ablex.

Kohn, K. (1986). The analysis of transfer. In E. Kellerman & M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.),Crosslinguisticinfluenceinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 21-34). New York: Pergamon.

Kuiken, F. & Vedder, I. (2007). Cognitive task complexity and linguistic performance in French L2 writing. In M. P. García Mayo (Ed.),Investigatingtasksinformallanguagelearning(pp. 117-135). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

LaBerge, D. (1975). Acquisition of automatic processing in perceptual and associative learning. In P. M. A. Rabbit & S. Dornic (Eds.),AttentionandperformanceⅤ (pp. 50-64). New York: Academic Press.

Labov, W. (1972).Sociolinguisticpatterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2009). Adjusting expectations: The study of complexity, accuracy, and fluency in second language acquisition.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 579-589.

Leeman, J., Arteagoitia, I., Fridman, B., & Doughty, C. (1995). Integrating attention to form with meaning: Focus on form in content-based Spanish instruction. In R. Schmidt (Ed.),Attentionandawarenessinforeignlanguagelearning(pp. 1-63). Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center.

Lehtonen, J. (1990). Foreign language acquisition and the development of automaticity. In H. W. Dechert (Ed.),CurrenttrendsinEuropeansecondlanguageacquisitionresearch(pp. 37-50). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Leow, R. P. (1997). Attention, awareness and foreign language behaviour.LanguageLearning, 47, 467-505.

Liceras, J. (1987). The role of intake in the determination of learners’ competence. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.),Inputinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 354-373). Rowley: Newbury House.

Logan, G. (1988). Toward an instance theory of automatization.PsychologicalReview, 95, 492-527.

McLaughlin, B. (1987).Theoriesofsecond-languagelearning. London: Edward Arnold.

McLaughlin, B. (1990). Restructuring.AppliedLinguistics, 11, 113-128.

McLaughlin, B., Rossman, T., & McLeod, B. (1983). Second language learning: An information-processing perspective.LanguageLearning, 33, 135-158.

McLeod, B. & McLaughlin, B. (1986). Restructuring or automaticity? Reading in a second language.LanguageLearning, 36, 109-123.

Muranoi, H. (2007). Output practice in the L2 classroom. In R. M. DeKeyser (Ed.),Practiceinasecondlanguage:Perspectivesfromappliedlinguisticsandcognitivepsychology(pp. 51-84). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, J. M. & Ortega, L. (2009). Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: The case of complexity.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 555-578.

Odlin, T. (1986). On the nature and use of explicit knowledge.InternationalReviewofAppliedLinguisticsinLanguageTeaching, 24, 123-144.

Ong, J. & Zhang, L.J. (2013). Effects of the manipulation of cognitive processes on EFL writers’ text quality.TESOLQuarterly, 47, 375-398.

Ortega, L. (1999). Planning and focus on form in L2 oral performance.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 21, 109-148.

Pallotti, G. (2009). CAF: Defining, refining, and differentiating constructs.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 590-601.

Philp, J. (2009). Pathways to proficiency: Learning experiences and attainment in implicit and explicit knowledge of English as a second language. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reiders (Eds.),Implicitandexplicitknowledgeinsecondlanguagelearning,testingandteaching(pp. 194-215). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Posner, M. I. & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain.AnnualReviewofNeuroscience, 13, 25-42.

Posner, M. I. & Snyder, C. R. R. (1975). Attention and cognitive control. In R. L. Solso (Ed.),Informationprocessingandcognition:TheLoyolaSymposium(pp. 55-85). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Robinson, P. (1995). Task complexity and second language narrative discourse.LanguageLearning, 45, 99-140.

Robinson, P. (1997). Generalizability and automaticity of second language learning under implicit, incidental, enhanced, and instructed conditions.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 19, 223-247.

Robinson, P. (2003). Attention and memory during SLA. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.),Thehandbookofsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 631-378). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Robinson, P. (2005). Cognitive complexity and task sequencing: Studies in a componential framework for second language task design.InternationalReviewofAppliedLinguistics, 45, 1-32.

Robinson, P., Cadierno, T., & Shirai, Y. (2009). Time and motion: Measuring the effects of the conceptual demands of tasks on second language speech production.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 533-554.

Roehr, K. (2007). Metalinguistic knowledge and language ability in university-level L2 learners.AppliedLinguistics, 29, 173-199.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 11, 129-158.

Schmidt, R. (1992). Psychological mechanisms underlying second language fluency.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 14, 357-385.

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.),Cognitionandsecondlanguageinstruction(pp. 3-32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Segalowitz, N. S. (1986). Skilled reading in the second language. In J. Vaid (Ed.),Languageprocessinginbilinguals:Psycholinguisticandneuropsychologicalperspectives(pp. 3-19). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Segalowitz, N. S. (2003). Automaticity and second languages. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.),Thehandbookofsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 382-408). Malden: Blackwell.

Seliger, H. W. (1979). On the nature and function of language rules in language teaching.TESOLQuarterly, 13, 359-369.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1986). The competence/control model, crosslinguistic influence and the creation of new grammars. In E. Kellerman & M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.),Crosslinguisticinfluenceinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 10-20). New York: Pergamon.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1991). Speaking to many minds: On the relevance of different types of language information for the L2 learner.SecondLanguageResearch, 7, 118-132.

Shehadeh, A. (1999). Non-native speakers’ production of modified comprehensible output and second language learning.LanguageLearning, 49, 627-675.

Shiffrin, R. M. (1976). Capacity limitations in information processing, attention, and memory. In W. K. Estes (Ed.),Handbookoflearningandcognitiveprocesses:Vol. 4.Attentionandmemory(pp. 177-236). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Shiffrin, R. M. & Dumais, S. T. (1981). The development of automatism. In J. R. Anderson (Ed.),Cognitiveskillsandtheiracquisition(pp. 111-140). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Shiffrin, R. M. & Schneider, W. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending, and a general theory.PsychologicalReview, 84, 127-190.

Skehan, P. (2009). Modelling second language performance: Integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexis.AppliedLinguistics, 30, 510-532.

Skehan, P. & Foster, P. (1999). The influence of task structure and processing conditions on narrative retellings.LanguageLearning, 49, 93-120.

Sorace, A. (1985). Metalinguistic knowledge and language use in acquisition-poor environments.AppliedLinguistics, 6, 239-254.

Stokes, J. D. (1985). Effects of student monitoring of verb inflection in Spanish.TheModernLanguageJournal, 69, 377-384.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensive input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.),Inputinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 235-253). Rowley: Newbury House.

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbookofresearchinsecondlanguageteachingandlearning(pp. 471-483). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards second language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 16, 371-391.

Tarone, E. (1988).Variationininterlanguage. London: Edward Arnold.

Towell, R., Hawkins, R., & Bazergui, N. (1996). The development of fluency in advanced learners of French.AppliedLinguistics, 17, 84-119.

Wickens, C. D. (1984). Processing resources in attention. In R. Parasuraman & D. R. Davies (Eds.),Varietiesofattention(pp. 63-102). Orlando: Academic Press.

Williams, J. N. (1999). Memory, attention, and inductive learning.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 21, 1-48.

Zietek, A. A. & Roehr, K. (2011). Metalinguistic knowledge and cognitive style in Polish classroom learners of English.System, 39, 417-426.

- 當(dāng)代外語研究的其它文章

- Thinking Metacognitively about Metacognition in Second and Foreign Language Learning, Teaching, and Research:Toward a Dynamic Metacognitive Systems Perspective

- Metacognition Theory and Research in Second Language Listening and Reading: A Comparative Critical Review

- Codeswitching in East Asian University EFL Classrooms:Reflecting Teachers’ Voices①

- Making a Commitment to Strategic-Reader Training

- Modality, Vocabulary Size and Question Type asMediators of Listening Comprehension Skill

- Learning Mandarin in Later Life: Can Old Dogs Learn New Tricks?①